Arthur Conan Doyle: Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red-Headed League (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Red-Headed League (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle I had called upon my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year and found him in deep conversation with a very stout, florid-faced, elderly gentleman with fiery red hair. With an apology for my intrusion, I was about to withdraw when Holmes pulled me abruptly into the room and closed the door behind me. "You could not possibly have come at a better time, my dear Watson," he said cordially. "I was afraid that you were engaged." "So I am. Very much so." "Then I can wait in the next room." "Not at all. This gentleman, Mr. Wilson, has been my partner and helper in many of my most successful cases, and I have no doubt that he will be of the utmost use to me in yours also." The stout gentleman half rose from his chair and gave a bob of greeting, with a quick little questioning glance from his small fat-encircled eyes. "Try the settee," said Holmes, relapsing into his armchair and putting his fingertips together, as was his custom when in judicial moods. "I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of everyday life. You have shown your relish for it by the enthusiasm which has prompted you to chronicle, and, if you will excuse my saying so, somewhat to embellish so many of my own little adventures." "Your cases have indeed been of the greatest interest to me," I observed. -

His Last Bow an Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes

His Last Bow An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes Arthur Conan Doyle This text is provided to you “as-is” without any warranty. No warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, are made to you as to the text or any medium it may be on, including but not limited to warranties of merchantablity or fitness for a particular purpose. This text was formatted from various free ASCII and HTML variants. See http://sherlock-holm.esfor an electronic form of this text and additional information about it. This text comes from the collection’s version 3.1. t was nine o’clock at night upon the sec- Then one comes suddenly upon something very ond of August—the most terrible August hard, and you know that you have reached the in the history of the world. One might limit and must adapt yourself to the fact. They I have thought already that God’s curse have, for example, their insular conventions which hung heavy over a degenerate world, for there was simply must be observed.” an awesome hush and a feeling of vague expectancy “Meaning ‘good form’ and that sort of thing?” in the sultry and stagnant air. The sun had long Von Bork sighed as one who had suffered much. set, but one blood-red gash like an open wound lay low in the distant west. Above, the stars were shin- “Meaning British prejudice in all its queer man- ing brightly, and below, the lights of the shipping ifestations. As an example I may quote one of my glimmered in the bay. -

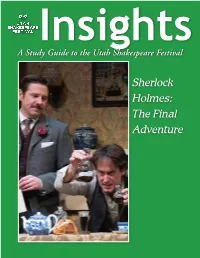

Sherlock Holmes: the Final Adventure the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2014, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn (left) and J. Todd Adams in Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, 2015. Contents Sherlock InformationHolmes: on the PlayThe Final Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the AdventurePlaywright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes? 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The play begins with the announcement of the death of Sherlock Holmes. It is 1891 London; and Dr. Watson, Holmes’s trusty colleague and loyal friend, tells the story of the famous detective’s last adventure. -

Automatic Writing and the Book of Mormon: an Update

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTOMATIC WRITING AND THE BOOK OF MORMON: AN UPDATE Brian C. Hales At a Church conference in 1831, Hyrum Smith invited his brother to explain how the Book of Mormon originated. Joseph declined, saying: “It was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.”1 His pat answer—which he repeated on several occasions—was simply that it came “by the gift and power of God.”2 Attributing the Book of Mormon’s origin to supernatural forces has worked well for Joseph Smith’s believers, then as well as now, but not so well for critics who seem certain natural abilities were responsible. For over 180 years, several secular theories have been advanced as explanations.3 The more popular hypotheses include plagiarism (of the Solomon Spaulding manuscript),4 collaboration (with Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, etc.),5 1. Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 23. 2. “Journal, 1835–1836,” in Journals, Volume. 1: 1832–1839, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 89; “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 5, Mar. 1, 1842, 707. 3. See Brian C. Hales, “Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study,” BYU Studies 58, no. -

20 Chapter Source Notes

20. Saul Among The Prophets 1. pages 375-377. Atlantic City, New Jersey...finally contacted him. Our recreation was composited from several accounts including Harry Houdini, A Magician Among The Spirits (New York : Arno Press, 1972), 149-158; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Edge Of The Unknown (New York : G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1930), 33-36; and “Editorial Notes” by Houdini, MUM, May, 1923, p.165. 2. page 379. Arthur Conan Doyle was born.... Details on Conan Doyle’s early life as it relates to spiritualism can be found in Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England: The Aquarian Press, 1989) and Bernard M.L. Ernst and Hereward Carrington, Houdini And Conan Doyle (New York : Albert and Charles Boni, Inc., 1932). 3. page 379. “showed me at last…” Doyle 1887 letter to spiritualist journal Light, cited in “The Man Who Believed In Fairies”, by Tom Huntington, Smithsonian, clipping in the archives of James Randi. 4. page 379. Lord Kitchener... Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England: The Aquarian Press, 1989), 110. 5. page 379. It was his book...knighthood in 1902. Ibid, 95. 6. page 379. revived him when...collaboration between the two men. “Conan Doyle’s Collaborator”, The Washington Post, April 10, 1902. 7. page 380. died after a long bout of tuberculosis... Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England : The Aquarian Press, 1989), 100. 8. page 380. married Jean Leckie... Ibid. 9. page 380. Jean’s friend Lily Loder-Symonds... Ibid, 110-112. 10. page 380. “Where were they?…signals.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The New Revelation, 1917, 10-11. -

A Thematic Reading of Sherlock Holmes and His Adaptations

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations. Britney Broyles University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Broyles, Britney, "Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2584. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2584 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, KY December 2016 Copyright 2016 by Britney Broyles All rights reserved CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 Dissertation Approved on November 22, 2016 by the following Dissertation Committee: Dr. -

His Last Bow Online

NPa3J (Mobile pdf) His Last Bow Online [NPa3J.ebook] His Last Bow Pdf Free Arthur Conan Doyle ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook 2016-04-11 2016-04-11File Name: B01E4S1688 | File size: 33.Mb Arthur Conan Doyle : His Last Bow before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised His Last Bow: His Last Bow: Some Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes is a collection of seven previously-published Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. Five of the stories were published in The Strand Magazine between September 1908 and December 1913. The final story, an epilogue about Holmes' war service, was first published in Collier's on 22 September 1917mdash;one month before the book's premier on 22 October. Some later editions of the collection include "The Adventure of the Cardboard Box", which was also collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894). The Strand published "The Adventure of Wistaria Lodge" as "A Reminiscence of Sherlock Holmes", and divided it into two parts, called "The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles" and "The Tiger of San Pedro". Later printings of His Last Bow correct Wistaria to Wisteria. Also, the first US edition adjusts the subtitle to Some Later Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes. All editions contain a brief preface, by "John H. Watson, M.D.". The preface assures readers that as of the date of publication (1917), Holmes is long retired from his profession of detectivemdash;but is still alive and well, albeit suffering from a touch of rheumatism. -

Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’S War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943

Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943 Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2018, 'Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943' Journal of British Cinema and Television, vol 15, no. 3, pp. 308-327. https://dx.doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425 DOI 10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425 ISSN 1743-4521 ESSN 1755-1714 Publisher: Edinburgh University Press This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press in Journal of British Cinema and Television. The Version of Record is available online at: http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943 Christopher Smith This article has been accepted for publication in the Journal of British Film and Television, 15(3), 2018. -

The Great Mystery of Life Beyond Death

THE GREAT MYSTERY OF LIFE BEYOND DEATH As dictated by a Spirit TO DIWAN BAHADUR HIRALAL L. KAJI INDIAN EDUCATIONAL SERVICE. BOMBAY. NEW BOOK COMPANY KITAB MAHAL. HORNBY ROAD BOMBAY 1938 Published by P» DirvjV.aw for the New Boob Company. KHnb Vabsb H orn by Road. Fort. Bombay t»nd Printed lit T c t f Printing 31. Tribhovan Road. Bombay 4, PREFACE No pleasure could be greater than the one I experience in presenting this volume to the public, in as much as I was given the unique privilege of expounding the Great Mystery of Life beyond Death as unfolded by the spirit o f the famous spiritualist, the late Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. I wish to state with all the clearness and sincerity at my command that no single idea expressed in this book is mine and that no single sentence as recorded is mine either. Beyond touching up some loose expressions here and there, the book is presented as spelt out letter by letter on the Ouija Board by the late Sir Arthur through my son Mr. Ashok H. Kaji and my nephew Mr. Subodh B. Kaji. I may as well confess that I have not read hitherto any book on spiritualism, nor have I read any religious, philosophical or metaphysical books of the Hindus or any other nation for the matter of that. M y son is a B. Sc. o f the Bombay University and my nephew is an M. Com. of the same University, and neither of them has devoted any thought whatsoever to the problems of the spirit-world, and the life beyond death, for as they have repeatedly declared, it is enough if they concentrated on THE GREAT MYSTERY OF LIFE BEYOND DEATH the problems o f the life before them in this world of the living instead of dabbling in those of the life in the world of the dead, which might well have an interest for people in the evening of life. -

By Marsha Pollak, ASH, BSI 1 Accompanied with Photographs Taken by Hiroko Nakashima 2

1 Reichenbach and Beyond—The Final Problem revisited By Marsha Pollak, ASH, BSI 1 Accompanied with photographs taken by Hiroko Nakashima 2 Not everything went according to script and it was almost as if Moriarty and his minions somehow controlled the weather. But three years after their splendid gathering “Alpine Adventures – A. Conan Doyle and Switzerland” in Davos, Switzerland, The Reichenbach Irregulars put together another stellar program on Sherlock Holmes and his Alpine adventures. This time the gathering was in the heart of the Bernese Oberland, not in the town of Meiringen, but above it in Hasliberg-Reuti. The conference consisted 1 Marsha Pollak, ASH, BSI, is a long time Sherlockian and retired librarian from California. Following in the footsteps of John Bennett Shaw and Francine Swift, Marsha has guided the oldest profession-oriented scion for more than 30 years, The Sub-Librarians Scion of the Baker Street Irregulars in the American Library Association. As part of her work for the BSI Trust, she is responsible for the BSI Oral History Project and is Series Editor for the BSI Press Professions Series. She and her husband enjoy traveling. 2 Hiroko Nakashima is a member of the Japan Sherlock Holmes Club and lives in Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan. She is a photographer as well as administrator in a Japanese IT company. She is a particular keen photographer when visiting Holmes and Doyle sites or when she attends Sherlockian events, for example in in London, Edinburgh, Dartmoor, Portsmouth or Undershaw. She has also been Switzerland, Italy, France and the Czech Republic. Hiroko sometime holds photo exhibitions in Japan and her pictures illustrate Japanese Sherlockian books. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

Conan Volume 16: the Song of Belit Free Download

CONAN VOLUME 16: THE SONG OF BELIT FREE DOWNLOAD Dr Brian Wood,Various | 176 pages | 19 Feb 2015 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616555245 | English | Milwaukee, United States Conan (comics) Chris rated it liked it Jun 10, Creepy, the quintessential horror comics anthology from Warren Publishing, always delivered a heaping helping Conan Volume 16: The Song of Belit Mechanized weapons of hominid destruction, murderous swamp beasts, ravenous alien hybrids, and other bizarre monsters Stories, books Books Conan books. Follow us. The Conan Volume 16: The Song of Belit Age Conan chronologies. Peak human physical condition, Melee weapons master, Knowledge and experience of fighting the supernatural. This trade has one of the most heeart breaking sequences I've ever read and i feel forever changed by it. From the page future war epic DMZ, the ecological disaster series The Massive, the American crime drama Briggs Land, and the groundbreaking lo-fi dystopia Channel Zero he has a year track record of marrying thoughtful world-building and political commentary with compelling and diverse characters. Parallel related story in Conan the Barbarian 66 and continues in Conan the Barbarian King Conan: Wolves Beyond the Border. Collects Conan: The Phantoms of the Black Coast 1—5 special comics sent to digital comics subscribers and not sold in the market. King Conan: The Scarlet Citadel. Absolutely makes no sense. Authors Creator Robert E. Brian Wood's history of published work includes over fifty volumes of genre-spanning original material. Jun 05, Ben rated it it was ok Shelves: graphic-novels. Home 1 Books 2. Conan Unchained! But that will be for a future volume to reveal, unless it's a blind alley conjured up by my fevered imagination.