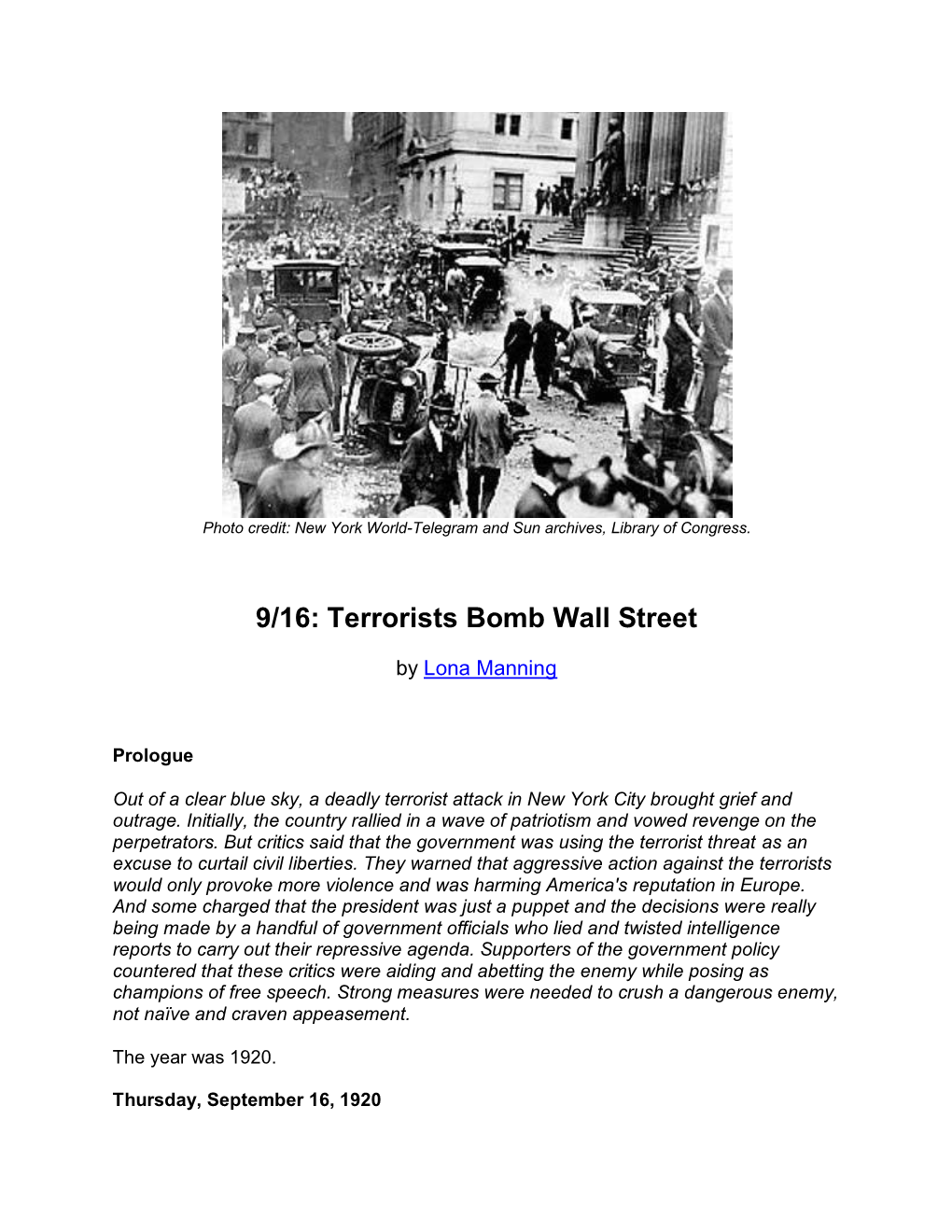

9/16: Terrorists Bomb Wall Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan

I Belong Only to Myself: The Life and Writings of Leda Rafanelli Excerpt from: CHAPTER VI Individualism and Futurism: Compagni in Milan ...Tracking back a few years, Leda and her beau Giuseppe Monanni had been invited to Milan in 1908 in order to take over the editorship of the newspaper The Human Protest (La Protesta Umana) by its directors, Ettore Molinari and Nella Giacomelli. The anarchist newspaper with the largest circulation at that time, The Human Protest was published from 1906–1909 and emphasized individual action and rebellion against institutions, going so far as to print articles encouraging readers to occupy the Duomo, Milan’s central cathedral.3 Hence it was no surprise that The Human Protest was subject to repeated seizures and the condemnations of its editorial managers, the latest of whom—Massimo Rocca (aka Libero Tancredi), Giovanni Gavilli, and Paolo Schicchi—were having a hard time getting along. Due to a lack of funding, editorial activity for The Human Protest was indefinitely suspended almost as soon as Leda arrived in Milan. She nevertheless became close friends with Nella Giacomelli (1873– 1949). Giacomelli had started out as a socialist activist while working as a teacher in the 1890s, but stepped back from political involvement after a failed suicide attempt in 1898, presumably over an unhappy love affair.4 She then moved to Milan where she met her partner, Ettore Molinari, and turned towards the anarchist movement. Her skepticism, or perhaps burnout, over the ability of humans to foster social change was extended to the anarchist movement, which she later claimed “creates rebels but doesn’t make anarchists.”5 Yet she continued on with her literary initiatives and support of libertarian causes all the same. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

Justice Crucified* a Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 8 Combined Issue 8-9 Spring/Autumn Article 21 1999 Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography Gil Fagiani Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Fagiani, Gil (1999) "Remember! Justice Crucified: A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 8 , Article 21. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol8/iss1/21 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Remember! Justice Crucified* A Synopsis, Chronology, and Selective Bibliography of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Gil Fagiani ____ _ The Enduring Legacy of the Sacco and Vanzetti Case Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, became celebrated martyrs in the struggle for social justice and politi cal freedom for millions of Italian Americans and progressive-minded people throughout the world. Having fallen into a police trap on May 5, 1920, they eventually were indicted on charges of participating in a payroll robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts in which a paymas ter and his guard were killed. After an unprecedented international campaign, they were executed in Boston on August 27, 1927. Intense interest in the case stemmed from a belief that Sacco and Vanzetti had not been convicted on the evidence but because they were Italian working-class immigrants who espoused a militant anarchist creed. -

Bad Time to Be a Cop

Price £3.00 Analysis: Theory: On Also inside 12 years the reality of New of economic this issue... Labour crisis Bad time to be a cop a be to time Bad Greece and G20 as the summer of rage builds rage of summer the as G20 and Greece Issue 229 Mid 2009 Editorial Welcome to issue 229 of Black Flag, the fourth to be published by the ‘new’ editorial collective since the re-launch in October 2007. We are still on-track to maintaining our bi- annual publishing objective; it is, however, difficult at times as each publication deadline looms closer, to meet this commitment. We are a small collective, and would once again like to take this opportunity to invite readers to submit articles and indeed, fresh bodies to get involved. Remember, the future of Black Flag, as always, lies with the support of its readership and the anarchist movement in general. We would like to see Black Flag flourish and become a regular (ideally quarterly), broad-based, non-sectarian class- struggle anarchist publication with a national identity. In Black Flag 228, we reported that we had approached the various anarchist federations and groups with a proposal for increased co- operation. Response has generally been slow and spasmodic. However, it has been enthusiastically taken up by the Anarchist Federation, who Barriers: Some of the obstacles laid out which stop us from changing things can seem have submitted an AF perspective insurmountable. Picture: Anya Brennan. on the current economic crisis and a report on a new anarchist archive in Nottingham, written by an AF member involved with the project. -

Popular Controversies in World History, Volume Four

Popular Controversies in World History © 2011 ABC-Clio. All Rights Reserved. Volume One Prehistory and Early Civilizations Volume Two The Ancient World to the Early Middle Ages Volume Three The High Middle Ages to the Modern World Volume Four The Twentieth Century to the Present © 2011 ABC-Clio. All Rights Reserved. Popular Controversies in World History INVESTIGATING HISTORY’S INTRIGUING QUESTIONS Volume Four The Twentieth Century to the Present Steven L. Danver, Editor © 2011 ABC-Clio. All Rights Reserved. Copyright 2011 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Popular controversies in world history : investigating history’s intriguing questions / Steven L. Danver, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-077-3 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0 (ebook) 1. History—Miscellanea. 2. Curiosities and wonders. I. Danver, Steven Laurence. D24.P67 2011 909—dc22 2010036572 ISBN: 978-1-59884-077-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-078-0 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America © 2011 ABC-Clio. -

Martyrdom Without End the Case Was Called a 'Never Ending Wrong.' It Still Inspires Wrong-Headedness

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit https://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118739039455001441 BOOKS Martyrdom Without End The case was called a 'never ending wrong.' It still inspires wrong-headedness. By Robert K. Landers Aug. 18, 2007 1201 a.m. ET Sacco & Vanzetti By Bruce Watson Viking, 433 pages, $25.95 Furious at the indictments of his fellow anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti -- charged with the murder of a shoe-factory paymaster and his guard in South Braintree, Mass. -- Mario Buda headed for New York City in September 1920. When he got there, he obtained a horse and wagon and placed in it a large dynamite bomb filled with cast-iron sash weights and equipped with a timer. On a Thursday morning, he drove to the corner of Wall and Broad Streets, parked across the street from J.P. Morgan and Co. and disappeared. The noontime explosion killed 33 people, injured several hundred and caused millions of dollars in property damage. His philosophical point made, Buda soon returned to Italy, beyond the reach of American law. William J. Flynn, director of the Justice Department's Bureau of Investigation, blamed the Wall Street bombing on the Galleanists, militant followers of the deported anarchist leader Luigi Galleani -- "the same group of terrorists," he said, that was responsible for coordinated bombings on June 2, 1919, in Washington and six other cities. Buda was indeed a Galleanist -- and so were Sacco and Vanzetti. -

First World War LESSON #6:8 Post-War America

Unit #6 First World War LESSON #6:8 Post-war America p. 200-203 LESSON #6:8 – Post War America (1/28) VOCABULARY • ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS p. 200-201: 17. How did the end of General strike the war and the soldiers Boston Strike of 1919 coming home effect the Steel Strike of 1920 workplace? p. 202-203 18. Why did we have such The Red Scare Reds fear and hatred toward a The Palmer Raids general strike? Deported Warren G. Harding’s “normalcy” HL to book 2m vid Financial Cost of war Which nation paid the most in US dollars? Financial Cost of the First World War Allied Powers Cost in Dollars in 1914-18 United States 22,625,253,000 Great Britain 35,334,012,000 France 24,265,583,000 Russia 22,293,950,000 Which nation paid the most in US dollars? Which nations followed next in spending the most? What was the total cost of First World War? Look at the next series of pictures. Describe what has happened. Human cost of war What’s the total number killed? Approx. 9 million killed What two nations paid the highest price? Russia & Germany “casualties” include both injured and killed What’s the total number of casualties? Approx. 29 million injured and killed Which “side” suffered the most deaths? What two “allied” nations suffered the majority of deaths? France and Russia – 55% of all allied deaths. What new information does this graph show? Civilian deaths, as well as military. Which “side” suffered the most total deaths? The Allies (Entente) Which nation suffered the fewest deaths? USA Sidebar facts: Who will pay? 1. -

Heroes and Villains

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 86 CutBank 86 Article 15 Winter 2017 Heroes and Villains Lacey Rowland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rowland, Lacey (2017) "Heroes and Villains," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 86 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss86/15 This Prose is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lacey Rowland successful in selling junk was the story. It was also how he sold himself to my mother. He told her stories of the desert, of the haunted pasts of men Heroes and Villains on the range. He enchanted her. • • • guess you could say my father was a magician. He could make things I disappear. Heartache, tears, a quarter behind the ear. A bottle of The funeral home transported my father’s body to Twin Falls, Idaho, the bourbon. Paychecks. He’d figured out how to make his heart stop once, closest point of civilization north of the Nevada border. My mother moved but couldn’t make it start again. His death was not an illusion. I didn’t to Boise from Twin after my father left, she couldn’t handle the small-town know how to feel about it at the time because I hadn’t seen my father in stares, the feeling of failure that lingers over the place. -

The Russian Workingmen's Association, Sometimes Called The

Speer: History of the Union of Russian Workers [April 8, 1919] 1 The Russian Workingmen’s Association, sometimes called the Union of Russian Workers (What It Is and How It Operates). [A Bureau of Investigation Internal Report] April 8, 1919 by Edgar B. Speer Report prepared in he Pittsburgh Office of the Bureau of Investigation. Document in DoJ/BoI Investigative Files, NARA M-1085, reel. 926, file 325570. At Pittsburgh, Pa. included some of the Russian Anarchists. There was trouble among the members of this organization and From the 6th to the 9th of January, 1919, the a Russian Anarchist by the name of William Shatov, 2nd Convention of the Russian Colonies was held in sometimes called Shatoff, who now occupies a promi- New York City. One hundred twenty-three delegates nent position in the Lenin Government in Russia; participated in the convention and they represented another Russian by the name of A. Rode, who is still 33,975 Russians, according to the Soviet of Working- living in the United States; a man by the name of men’s Deputies of the US and Canada Weekly. The inde- Dieproski; a Finnish Anarchist by the name of Peter- pendent element was represented by 60 delegates; son, who it is understood is still living in the United Union of Russian Workers, 49; Socialists, 9; Indus- States under the name of Peters; and several others. trial Workers of the World, 2; and Anarchists, 3. Dur- These met and formed a Russian Anarchist Group. ing the convention, Peter Bianki, who represented the The Group was in existence about 6 months when it Union of Russian Workers of the United States and began the publication of a monthly paper called Golos Canada and the Anarchists, declared from the con- Truda (Voice of Labor). -

Sacco & Vanzetti

, ' \ ·~ " ~h,S (1'(\$'104 frtn"\i tover) p 0 S t !tV 4 ~ b fa. V\ k ,~ -1 h ~ o '(";,5 I (\ (J. \ • . , SACCO and V ANZETTI ~: LABOR'S MARTYRS t By MAX SHACHTMAN TWENTY-FIVE CENTS f t PubLished by the INTERNATIONAL LABOR DEFENSE NEW YORK 1927 SACCO and VANZETTI LABOR'S MAR TYRS l5jGi~m~""Z"""G':L".~-;,.2=r.~ OWHERE can history find a parallel to m!!-~~m * ~ the case of the two Italian immigrant \<I;j N ~ workers, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo ~ ~ Vanzetti. Many times before this there ' ~r.il' @~ have been great social upheavals, revolu- i,!:'""";&- J f d I h ~ - ~C{til,}. tlOns, pro oun popu ar movements t at have swept thousands and millions of people into powerful tides of action. But, since the Russian Bolshe vik revolution, where has there yet been a cause that has drawn into its wake the people, not of this or that land, but of all countries, millions from every part and corner of the world; the workers in the metropolis, the peasant on the land, the people of the half-forgotten islands of the sea, men and women and children in all walks of life? There have been other causes that had just as passionate and loyal an adherence, but none with so multitudinous an army. THE PALMER RAIDS If the Sacco-Vanzetti case is regarded as an accidental series of circumstances in which two individuals were unjustly accused of a crime, and then convicted by some inexplicable and unusual flaw in the otherwise pure fabric of justice, it will be quite impossible to understand the first thing about this historic fight. -

The Masses Index 1911-1917

The Masses Index 1911-1917 1 Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series THE MASSES INDEX 1911-1917 1911-1917 By Theodore F. Watts \ Forthcoming volumes in the "Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series:" The Liberator (1918-1924) The New Masses (Monthly, 1926-1933) The New Masses (Weekly, 1934-1948) Foreword The handful ofyears leading up to America's entry into World War I was Socialism's glorious moment in America, its high-water mark ofenergy and promise. This pregnant moment in time was the result ofdecades of ferment, indeed more than 100 years of growing agitation to curb the excesses of American capitalism, beginning with Jefferson's warnings about the deleterious effects ofurbanized culture, and proceeding through the painful dislocation ofthe emerging industrial economy, the ex- cesses ofspeculation during the Civil War, the rise ofthe robber barons, the suppression oflabor unions, the exploitation of immigrant labor, through to the exposes ofthe muckrakers. By the decade ofthe ' teens, the evils ofcapitalism were widely acknowledged, even by champions ofthe system. Socialism became capitalism's logical alternative and the rallying point for the disenchanted. It was, of course, merely a vision, largely untested. But that is exactly why the socialist movement was so formidable. The artists and writers of the Masses didn't need to defend socialism when Rockefeller's henchmen were gunning down mine workers and their families in Ludlow, Colorado. Eventually, the American socialist movement would shatter on the rocks ofthe Russian revolution, when it was finally confronted with the reality ofa socialist state, but that story comes later, after the Masses was run from the stage. -

There Will Be Oil: the Celebration and Inevitability of Petroleum Through Upton Sinclair and Paul Thomas Anderson

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2018 There Will Be Oil: The eleC bration and Inevitability of Petroleum through Upton Sinclair and Paul Thomas Anderson Sarah Mae Fleming [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fleming, Sarah Mae, "There Will Be Oil: The eC lebration and Inevitability of Petroleum through Upton Sinclair and Paul Thomas Anderson" (2018). Honors Projects Overview. 142. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/142 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. There Will Be Oil: The Celebration and Inevitability of Petroleum through Upton Sinclair and Paul Thomas Anderson Sarah Mae Fleming English 492 Undergraduate Honors Thesis “Godspeed! Pope given a Lamborghini, replete in papal gold and white.”1 This BBC news feed and the attendant video went viral in a matter of moments providing a glimpse of the intricate relationship between western culture and petroleum. Pope Francis blesses the custom Lamborghini, before it is sent to a charity auction. Excess, consumption, capitalism, petroleum, religion, culture—all combined during a blessing of an expensive automobile by the pontiff. This short video gives witness to how oil quietly soaks our world. I started this project with the intention of conducting a Marxist study of the novel Oil! (Upton Sinclair, 1927) and the film There Will Be Blood, (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007) in the context of American Westerns and their relationship to capitalism.