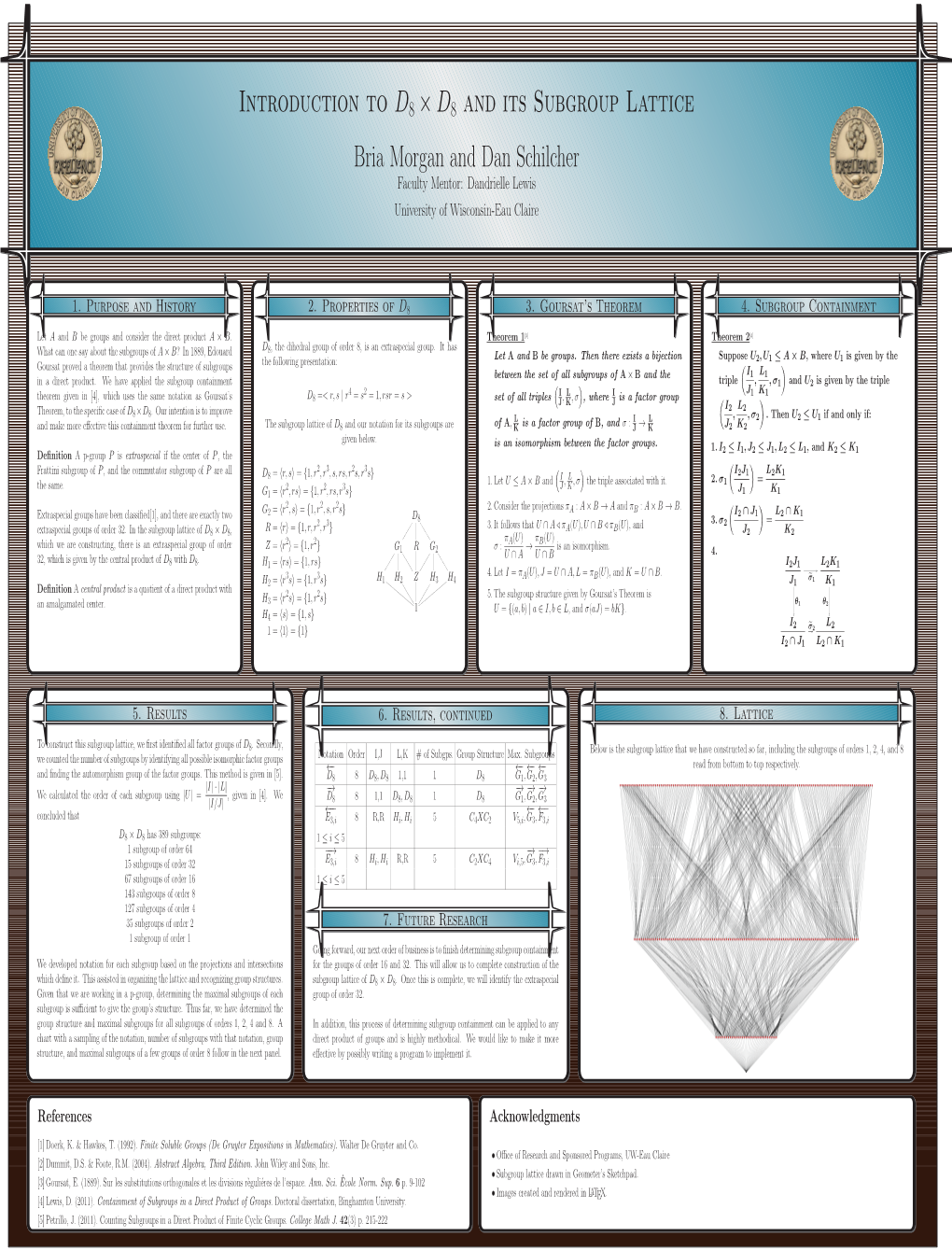

Introduction to D8 × D8 and Its Subgroup Lattice Bria Morgan and Dan Schilcher Faculty Mentor: Dandrielle Lewis University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Homology of Peiffer Products of Groups

New York Journal of Mathematics New York J. Math. 6 (2000) 55–71. The Homology of Peiffer Products of Groups W. A. Bogley and N. D. Gilbert Abstract. The Peiffer product of groups first arose in work of J.H.C. White- head on the structure of relative homotopy groups, and is closely related to problems of asphericity for two-complexes. We develop algebraic methods for computing the second integral homology of a Peiffer product. We show that a Peiffer product of superperfect groups is superperfect, and determine when a Peiffer product of cyclic groups has trivial second homology. We also introduce a double wreath product as a Peiffer product. Contents Introduction 55 1. The low-dimensional homology of products of subgroups 57 2. Twisted bilinear relations 60 3. The structure of SG∗H 61 4. Computations 63 References 70 Introduction Given two groups acting on each other by automorphisms, it is natural to ask whether these groups can be embedded in an overgroup in such a way that the given actions are realized by conjugation. If the actions are trivial, this can be done simply by forming the direct product of the two groups. In general, the question has a negative answer. One is led to the following construction. Let G and H be groups and suppose we are given fixed actions (g, h) 7→ gh and (h, g) 7→ hg of each group on the other. Received October 1, 1999. Mathematics Subject Classification. 20J05, 20E22, 20F05. Key words and phrases. homology, Peiffer product, asphericity, two-complex, double wreath product. -

Frattini Subgroups and -Central Groups

Pacific Journal of Mathematics FRATTINI SUBGROUPS AND 8-CENTRAL GROUPS HOMER FRANKLIN BECHTELL,JR. Vol. 18, No. 1 March 1966 PACIFIC JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICS Vol. 18, No. 1, 1966 FRATTINI SUBGROUPS AND φ-CENTRAL GROUPS HOMER BECHTELL 0-central groups are introduced as a step In the direction of determining sufficiency conditions for a group to be the Frattini subgroup of some unite p-gronp and the related exten- sion problem. The notion of Φ-centrality arises by uniting the concept of an E-group with the generalized central series of Kaloujnine. An E-group is defined as a finite group G such that Φ(N) ^ Φ(G) for each subgroup N ^ G. If Sίf is a group of automorphisms of a group N, N has an i^-central series ι a N = No > Nt > > Nr = 1 if x~x e N3- for all x e Nj-lf all a a 6 £%f, x the image of x under the automorphism a e 3ίf y i = 0,l, •••, r-1. Denote the automorphism group induced OR Φ(G) by trans- formation of elements of an £rgroup G by 3ίf. Then Φ{£ίf) ~ JP'iΦiG)), J^iβiG)) the inner automorphism group of Φ(G). Furthermore if G is nilpotent9 then each subgroup N ^ Φ(G), N invariant under 3ίf \ possess an J^-central series. A class of niipotent groups N is defined as ^-central provided that N possesses at least one niipotent group of automorphisms ££'' Φ 1 such that Φ{βίf} — ,J^(N) and N possesses an J^-central series. Several theorems develop results about (^-central groups and the associated ^^-central series analogous to those between niipotent groups and their associated central series. -

ON the INTERSECTION NUMBER of FINITE GROUPS Humberto Bautista Serrano University of Texas at Tyler

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler Math Theses Math Spring 5-14-2019 ON THE INTERSECTION NUMBER OF FINITE GROUPS Humberto Bautista Serrano University of Texas at Tyler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/math_grad Part of the Algebra Commons, and the Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics Commons Recommended Citation Bautista Serrano, Humberto, "ON THE INTERSECTION NUMBER OF FINITE GROUPS" (2019). Math Theses. Paper 9. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/1332 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Math at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in Math Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON THE INTERSECTION NUMBER OF FINITE GROUPS by HUMBERTO BAUTISTA SERRANO A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Mathematics Kassie Archer, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler April 2019 c Copyright by Humberto Bautista Serrano 2019 All rights reserved Acknowledgments Foremost I would like to express my gratitude to my two excellent advisors, Dr. Kassie Archer at UT Tyler and Dr. Lindsey-Kay Lauderdale at Towson University. This thesis would never have been possible without their support, encouragement, and patience. I will always be thankful to them for introducing me to research in mathematics. I would also like to thank the reviewers, Dr. Scott LaLonde and Dr. David Milan for pointing to several mistakes and omissions and enormously improving the final version of this thesis. -

Minimal Generation of Transitive Permutation Groups

Minimal generation of transitive permutation groups Gareth M. Tracey∗ Mathematics Institute, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, United Kingdom October 30, 2017 Abstract This paper discusses upper bounds on the minimal number of elements d(G) required to generate a transitive permutation group G, in terms of its degree n, and its order G . In particular, we | | reduce a conjecture of L. Pyber on the number of subgroups of the symmetric group Sym(n). We also prove that our bounds are best possible. 1 Introduction A well-developed branch of finite group theory studies properties of certain classes of permutation groups as functions of their degree. The purpose of this paper is to study the minimal generation of transitive permutation groups. For a group G, let d(G) denote the minimal number of elements required to generate G. In [21], [7], [26] and [28], it is shown that d(G)= O(n/√log n) whenever G is a transitive permutation group of degree n 2 (here, and throughout this paper, “ log ” means log to the base 2). A beautifully ≥ constructed family of examples due to L. Kov´acs and M. Newman shows that this bound is ‘asymp- totically best possible’ (see Example 6.10), thereby ending the hope that a bound of d(G)= O(log n) could be proved. The constants involved in these theorems, however, were never estimated. We prove: arXiv:1504.07506v3 [math.GR] 30 Jan 2018 Theorem 1.1. Let G be a transitive permutation group of degree n 2. Then ≥ (1) d(G) cn ,where c := 1512660 log (21915)/(21915) = 0.920581 . -

Nilpotent Groups

Chapter 7 Nilpotent Groups Recall the commutator is given by [x, y]=x−1y−1xy. Definition 7.1 Let A and B be subgroups of a group G.Definethecom- mutator subgroup [A, B]by [A, B]=! [a, b] | a ∈ A, b ∈ B #, the subgroup generated by all commutators [a, b]witha ∈ A and b ∈ B. In this notation, the derived series is given recursively by G(i+1) = [G(i),G(i)]foralli. Definition 7.2 The lower central series (γi(G)) (for i ! 1) is the chain of subgroups of the group G defined by γ1(G)=G and γi+1(G)=[γi(G),G]fori ! 1. Definition 7.3 AgroupG is nilpotent if γc+1(G)=1 for some c.Theleast such c is the nilpotency class of G. (i) It is easy to see that G " γi+1(G)foralli (by induction on i). Thus " if G is nilpotent, then G is soluble. Note also that γ2(G)=G . Lemma 7.4 (i) If H is a subgroup of G,thenγi(H) " γi(G) for all i. (ii) If φ: G → K is a surjective homomorphism, then γi(G)φ = γi(K) for all i. 83 (iii) γi(G) is a characteristic subgroup of G for all i. (iv) The lower central series of G is a chain of subgroups G = γ1(G) ! γ2(G) ! γ3(G) ! ··· . Proof: (i) Induct on i.Notethatγ1(H)=H " G = γ1(G). If we assume that γi(H) " γi(G), then this together with H " G gives [γi(H),H] " [γi(G),G] so γi+1(H) " γi+1(G). -

Lattice of Subgroups of a Group. Frattini Subgroup

FORMALIZED MATHEMATICS Vol.2,No.1, January–February 1991 Universit´e Catholique de Louvain Lattice of Subgroups of a Group. Frattini Subgroup Wojciech A. Trybulec1 Warsaw University Summary. We define the notion of a subgroup generated by a set of elements of a group and two closely connected notions, namely lattice of subgroups and the Frattini subgroup. The operations on the lattice are the intersection of subgroups (introduced in [18]) and multiplication of subgroups, which result is defined as a subgroup generated by a sum of carriers of the two subgroups. In order to define the Frattini subgroup and to prove theorems concerning it we introduce notion of maximal subgroup and non-generating element of the group (see page 30 in [6]). The Frattini subgroup is defined as in [6] as an intersection of all maximal subgroups. We show that an element of the group belongs to the Frattini subgroup of the group if and only if it is a non-generating element. We also prove theorems that should be proved in [1] but are not. MML Identifier: GROUP 4. The notation and terminology used here are introduced in the following articles: [3], [13], [4], [11], [20], [10], [19], [8], [16], [5], [17], [2], [15], [18], [14], [12], [21], [7], [9], and [1]. Let D be a non-empty set, and let F be a finite sequence of elements of D, and let X be a set. Then F − X is a finite sequence of elements of D. In this article we present several logical schemes. The scheme SubsetD deals with a non-empty set A, and a unary predicate P, and states that: {d : P[d]}, where d is an element of A, is a subset of A for all values of the parameters. -

Bounds of Some Invariants of Finite Permutation Groups Hülya Duyan

Bounds of Some Invariants of Finite Permutation Groups H¨ulya Duyan Department of Mathematics and its Applications Central European University Budapest, Hungary CEU eTD Collection A dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics CEU eTD Collection Abstract Let Ω be a non-empty set. A bijection of Ω onto itself is called a permutation of Ω and the set of all permutations forms a group under composition of mapping. This group is called the symmetric group on Ω and denoted by Sym(Ω) (or Sym(n) or Sn where jΩj = n). A permutation group on Ω is a subgroup of Sym(Ω). Until 1850's this was the definition of group. Although this definition and the ax- iomatic definition are the same, usually what we first learn is the axiomatic approach. The reason is to not to restrict the group elements to being permutations of some set Ω. Let G be a permutation group. Let ∼ be a relation on Ω such that α ∼ β if and only if there is a transformation g 2 G which maps α to β where α; β 2 Ω. ∼ is an equivalence relation on Ω and the equivalence classes of ∼ are the orbits of G. If there is one orbit then G is called transitive. Assume that G is intransitive and Ω1;:::; Ωt are the orbits of G on Ω. G induces a transitive permutation group on each Ωi, say Gi where i 2 f1; : : : ; tg. Gi are called the transitive constituents of G and G is a subcartesian product of its transitive constituents. -

A Survey on Automorphism Groups of Finite P-Groups

A Survey on Automorphism Groups of Finite p-Groups Geir T. Helleloid Department of Mathematics, Bldg. 380 Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-2125 [email protected] February 2, 2008 Abstract This survey on the automorphism groups of finite p-groups focuses on three major topics: explicit computations for familiar finite p-groups, such as the extraspecial p-groups and Sylow p-subgroups of Chevalley groups; constructing p-groups with specified automorphism groups; and the discovery of finite p-groups whose automorphism groups are or are not p-groups themselves. The material is presented with varying levels of detail, with some of the examples given in complete detail. 1 Introduction The goal of this survey is to communicate some of what is known about the automorphism groups of finite p-groups. The focus is on three topics: explicit computations for familiar finite p-groups; constructing p-groups with specified automorphism groups; and the discovery of finite p-groups whose automorphism groups are or are not p-groups themselves. Section 2 begins with some general theorems on automorphisms of finite p-groups. Section 3 continues with explicit examples of automorphism groups of finite p-groups found in the literature. This arXiv:math/0610294v2 [math.GR] 25 Oct 2006 includes the computations on the automorphism groups of the extraspecial p- groups (by Winter [65]), the Sylow p-subgroups of the Chevalley groups (by Gibbs [22] and others), the Sylow p-subgroups of the symmetric group (by Bon- darchuk [8] and Lentoudis [40]), and some p-groups of maximal class and related p-groups. -

A Classification of Clifford Algebras As Images of Group Algebras of Salingaros Vee Groups

DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS TECHNICAL REPORT A CLASSIFICATION OF CLIFFORD ALGEBRAS AS IMAGES OF GROUP ALGEBRAS OF SALINGAROS VEE GROUPS R. Ablamowicz,M.Varahagiri,A.M.Walley November 2017 No. 2017-3 TENNESSEE TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY Cookeville, TN 38505 A Classification of Clifford Algebras as Images of Group Algebras of Salingaros Vee Groups Rafa lAb lamowicz, Manisha Varahagiri and Anne Marie Walley Abstract. The main objective of this work is to prove that every Clifford algebra C`p;q is R-isomorphic to a quotient of a group algebra R[Gp;q] modulo an ideal J = (1 + τ) where τ is a central element of order 2. p+q+1 Here, Gp;q is a 2-group of order 2 belonging to one of Salingaros isomorphism classes N2k−1;N2k; Ω2k−1; Ω2k or Sk. Thus, Clifford al- gebras C`p;q can be classified by Salingaros classes. Since the group algebras R[Gp;q] are Z2-graded and the ideal J is homogeneous, the quotient algebras R[G]=J are Z2-graded. In some instances, the isomor- ∼ phism R[G]=J = C`p;q is also Z2-graded. By Salingaros Theorem, the groups Gp;q in the classes N2k−1 and N2k are iterative central products of the dihedral group D8 and the quaternion group Q8, and so they are extra-special. The groups in the classes Ω2k−1 and Ω2k are central products of N2k−1 and N2k with C2 × C2, respectively. The groups in the class Sk are central products of N2k or N2k with C4. Two algorithms to factor any Gp;q into an internal central product, depending on the class, are given. -

Random Generation of Finite and Profinite Groups and Group

Annals of Mathematics 173 (2011), 769{814 doi: 10.4007/annals.2011.173.2.4 Random generation of finite and profinite groups and group enumeration By Andrei Jaikin-Zapirain and Laszl´ o´ Pyber Abstract We obtain a surprisingly explicit formula for the number of random ele- ments needed to generate a finite d-generator group with high probability. As a corollary we prove that if G is a d-generated linear group of dimension n then cd + log n random generators suffice. Changing perspective we investigate profinite groups F which can be generated by a bounded number of elements with positive probability. In response to a question of Shalev we characterize such groups in terms of certain finite quotients with a transparent structure. As a consequence we settle several problems of Lucchini, Lubotzky, Mann and Segal. As a byproduct of our techniques we obtain that the number of r-relator groups of order n is at most ncr as conjectured by Mann. 1. Introduction Confirming an 1882 conjecture of Netto [40], Dixon [13] proved in 1969 that two randomly chosen elements generate the alternating group Alt(n) with probability that tends to 1 as n ! 1. This was extended in [21] and [24] to arbitrary sequences of non-abelian finite simple groups. Such results form the basis of applying probabilistic methods to the solution of various problems concerning finite simple groups [50]. Interest in random generation of more general families of finite groups arose when it was realized that randomized algorithms play a critical role in handling matrix groups [4]. -

Threads Through Group Theory

Contemporary Mathematics Threads Through Group Theory Persi Diaconis Abstract. This paper records the path of a letter that Marty Isaacs wrote to a stranger. The tools in the letter are used to illustrate a different way of studying random walk on the Heisenberg group. The author also explains how the letter contributed to the development of super-character theory. 1. Introduction Marty Isaacs believes in answering questions. They can come from students, colleagues, or perfect strangers. As long as they seem serious, he usually gives it a try. This paper records the path of a letter that Marty wrote to a stranger (me). His letter was useful; it is reproduced in the Appendix and used extensively in Section 3. It led to more correspondence and a growing set of extensions. Here is some background. I am a mathematical statistician who, for some unknown reason, loves finite group theory. I was trying to make my own peace with a corner of p-group theory called extra-special p-groups. These are p-groups G with center Z(G) equal to commutator subgroup G0 equal to the cyclic group Cp. I found considerable literature about the groups [2, Sect. 23], [22, Chap. III, Sect. 13], [39, Chap. 4, Sect. 4] but no \stories". Where do these groups come from? Who cares about them, and how do they fit into some larger picture? My usual way to understand a group is to invent a \natural" random walk and study its rate of convergence to the uniform distribution. This often calls for detailed knowledge of the conjugacy classes, characters, and of the geometry of the Cayley graph underlying the walk. -

8 Nilpotent Groups

8 Nilpotent groups Definition 8.1. A group G is nilpotent if it has a normal series G = G0 · G1 · G2 · ¢ ¢ ¢ · Gn = 1 (1) where Gi=Gi+1 · Z(G=Gi+1) (2) We call (1) a central series of G of length n. The minimal length of a central series is called the nilpotency class of G. For example, an abelian group is nilpotent with nilpotency class · 1. Some trivial observations: First, nilpotent groups are solvable since (2) implies that Gi=Gi+1 is abelian. Also, nilpotent groups have nontrivial cen- ters since Gn¡1 · Z(G). Conversely, the fact that p-groups have nontrivial centers implies that they are nilpotent. Theorem 8.2. Every finite p-group is nilpotent. Proof. We will construct a central series of a p-group G from the bottom up. k The numbering will be reversed: Gn¡k = Z (G) which are defined as follows. 0 0. Z (G) = 1 (= Gn where n is undetermined). 1. Z1(G) = Z(G)(> 1 if G is a p-group). 2. Given Zk(G), let Zk+1(G) be the subgroup of G which contains Zk(G) and corresponds to the center of G=Zk(G), i.e., so that Zk+1(G)=Zk(G) = Z(G=Zk(G)) Since G=Zk(G) is a p-group it has a nontrivial center, making Zk+1(G) > Zk(G) unless Zk(G) = G. Since G is finite we must have Zn(G) = G for some n making G nilpotent of class · n. For an arbitrary group G the construction above gives a (possibly infinite) sequence of characteristic subgroups of G: 1 = Z0(G) · Z(G) = Z1(G) · Z2(G) · ¢ ¢ ¢ We call this the upper central series of G (because it has the property that n¡k Z (G) ¸ Gk for any central series fGkg of length n.