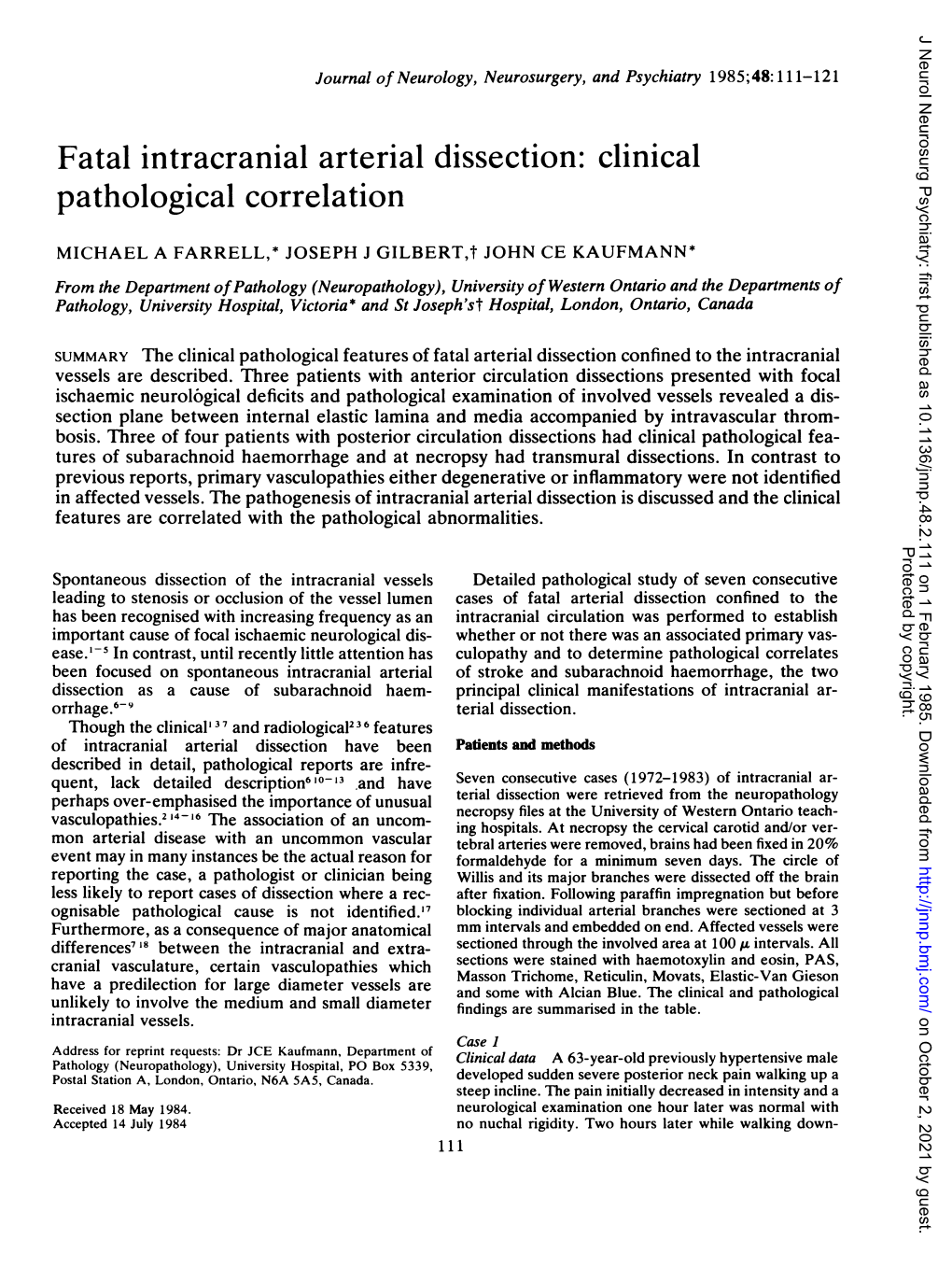

Fatal Intracranial Arterial Dissection: Clinical Pathological Correlation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endovascular Treatment of Stroke Caused by Carotid Artery Dissection

brain sciences Case Report Endovascular Treatment of Stroke Caused by Carotid Artery Dissection Grzegorz Meder 1,* , Milena Swito´ ´nska 2,3 , Piotr Płeszka 2, Violetta Palacz-Duda 2, Dorota Dzianott-Pabijan 4 and Paweł Sokal 3 1 Department of Interventional Radiology, Jan Biziel University Hospital No. 2, Ujejskiego 75 Street, 85-168 Bydgoszcz, Poland 2 Stroke Intervention Centre, Department of Neurosurgery and Neurology, Jan Biziel University Hospital No. 2, Ujejskiego 75 Street, 85-168 Bydgoszcz, Poland; [email protected] (M.S.);´ [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (V.P.-D.) 3 Department of Neurosurgery and Neurology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toru´n,Ludwik Rydygier Collegium Medicum, Ujejskiego 75 Street, 85-168 Bydgoszcz, Poland; [email protected] 4 Neurological Rehabilitation Ward Kuyavian-Pomeranian Pulmonology Centre, Meysnera 9 Street, 85-472 Bydgoszcz, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-52-3655-143; Fax: +48-52-3655-364 Received: 23 September 2020; Accepted: 27 October 2020; Published: 30 October 2020 Abstract: Ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion (LVO) is a devastating condition. Most LVOs are embolic in nature. Arterial dissection is responsible for only a small proportion of LVOs, is specific in nature and poses some challenges in treatment. We describe 3 cases where patients with stroke caused by carotid artery dissection were treated with mechanical thrombectomy and extensive stenting with good outcome. We believe that mechanical thrombectomy and stenting is a treatment of choice in these cases. Keywords: stroke; artery dissection; endovascular treatment; stenting; mechanical thrombectomy 1. -

Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms And

Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage SECTION VIII, Part I Results of the Treatment of Intracranial Aneurysms by Occlusion of the Carotid Artery in the Neck HIRO NISHIOKA, M.D.* Introduction In a late postoperative study of retinal artery CCLUSION of the cervical portion of the pressures in 13 patients with carotid liga- carotid artery has been employed tion, Christiansson '6~ found eight patients O since 1885 as a definitive treatment who had maintained pressure drops of 20 per for intracranial aneurysm. The resultant re- cent or more over a period of from 1 to 13 duction of intra-arterial pressure is expected years. The observation that there was stasis to reduce the likelihood of subsequent of blood within the aneuwsmal sac after hemorrhage. The alteration of blood flow carotid occlusion was made at angiography characteristics within the aneurysmal sac by Eeker and Riemenschneider '51. During may encourage thrombosis with organization digital carotid occlusion, they found that and fibrosis, which would strengthen the wall Diodrast remained within the sac for over a or obliterate the sac. That pressure can be minute, and, in the same patient, angiog- reduced effectively in the internal carotid raphy performed one week after partial artery by proximal internal or common ca- occlusion of the common carotid by a tan- rotid occlusion has been substantiated amply talum clip showed no filling of the aneurysm. by the works of many authors. However, Aneurysms may decrease visibly in size or pressure reductions distal to the bifurcation become progressively thrombosed after ca- of the internal carotid artery following ca- rotid ligation. -

Peripheral Arterial Disease

SEMINAR Seminar Peripheral arterial disease Kenneth Ouriel Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD) most frequently presents with pain during ambulation, which is known as “intermittent claudication”. Some relief of symptoms is possible with exercise, pharmacotherapy, and cessation of smoking. The risk of limb-loss is overshadowed by the risk of mortality from coexistent coronary artery and cerebrovascular atherosclerosis. Primary therapy should be directed at treating the generalised atherosclerotic process, managing lipids, blood sugar, and blood pressure. By contrast, the risk of limb-loss becomes substantial when there is pain at rest, ischaemic ulceration, or gangrene. Interventions such as balloon angioplasty, stenting, and surgical revascularisation should be considered in these patients with so-called “critical limb ischaemia”. The choice of the intervention is dependent on the anatomy of the stenotic or occlusive lesion; percutaneous interventions are appropriate when the lesion is focal and short but longer lesions must be treated with surgical revascularisation to achieve acceptable long-term outcome. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) comprises those entities ankle systolic pressure measured with a blood pressure at which result in obstruction to blood flow in the arteries, the malleolar level by the higher of the two brachial exclusive of the coronary and intracranial vessels. pressures. Defining PAD by an ankle-brachial index of Although the definition of PAD technically includes less than 0·95, a frequency of 6·9% was observed in problems within the extracranial carotid circulation, the patients aged 45–74 years, only 22% of whom had upper extremity arteries, and the mesenteric and renal symptoms.5 The frequency of intermittent claudication circulation, we will focus on chronic arterial occlusive increases dramatically with advancing age, ranging from disease in the arteries to the legs. -

Impacts of Internal Carotid Artery Revascularization on Flow in Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysm: a Preliminary Multiscale Numerical Investigation

applied sciences Article Impacts of Internal Carotid Artery Revascularization on Flow in Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysm: A Preliminary Multiscale Numerical Investigation Guang-Yu Zhu 1, Yuan Wei 1, Ya-Li Su 2, Qi Yuan 1 and Cheng-Fu Yang 3,* 1 School of Energy and Power Engineering, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, China; [email protected] (G.-Y.Z.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (Q.Y.) 2 School of Mechanical Engineering, Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an 710065, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering, National University of Kaohsiung, No. 700, Kaohsiung University Rd., Nan-Tzu District, Kaohsiung 811, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 September 2019; Accepted: 26 September 2019; Published: 3 October 2019 Abstract: The optimal management strategy of patients with concomitant anterior communicating artery aneurysm (ACoAA) and internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis is unclear. This study aims to evaluate the impacts of unilateral ICA revascularization on hemodynamics factors associated with rupture in an ACoAA. In the present study, a multiscale computational model of ACoAA was developed by coupling zero-dimensional (0D) models of the cerebral vascular system with a three-dimensional (3D) patient-specific ACoAA model. Distributions of flow patterns, wall shear stress (WSS), relative residence time (RRT) and oscillating shear index (OSI) in the ACoAA under left ICA revascularization procedure were quantitatively assessed by using transient computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations. Our results showed that the revascularization procedures significantly changed the hemodynamic environments in the ACoAA. The flow disturbance in the ACoAA was enhanced by the resumed flow from the affected side. -

The Surgical Management of Pituitary Apoplexy with Occluded Internal Carotid Artery and Hidden Intracranial Aneurysm: Illustrative Case

J Neurosurg Case Lessons 2(5):CASE20115, 2021 DOI: 10.3171/CASE20115 The surgical management of pituitary apoplexy with occluded internal carotid artery and hidden intracranial aneurysm: illustrative case *Jian-Dong Zhu, MD, Sungel Xie, MD, Ling Xu, MD, Ming-Xiang Xie, MD, and Shun-Wu Xiao, MD Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Guizhou, China BACKGROUND Approximately 0.6% to 12% of cases of pituitary adenoma are complicated by apoplexy, and nearly 6% of pituitary adenomas are comorbid aneurysms. Occlusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) with hidden intracranial aneurysm due to compression by an apoplectic pituitary adenoma is extremely rare; thus, the surgical strategy is also unknown. OBSERVATIONS The authors reported the case of a 48-year-old man with a large pituitary adenoma with coexisting ICA occlusion. After endoscopic transnasal surgery, repeated computed tomography angiography (CTA) demonstrated reperfusion of the left ICA but with a new-found aneurysm in the left posterior communicating artery; thus, interventional aneurysm embolization was performed. With stable recovery and improved neurological condition, the patient was discharged for rehabilitation training. LESSONS For patients with pituitary apoplexy accompanied by a rapid decrease of neurological conditions, emergency decompression through endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal resection can achieve satisfactory results. However, with occlusion of the ICA by enlarged pituitary adenoma or pituitary apoplexy, a hidden but rare intracranial aneurysm may be considered when patients are at high risk of such vascular disease as aneurysm, and gentle intraoperative manipulations are required. Performing CTA or digital subtraction angiography before and after surgery can effectively reduce the missed diagnosis of comorbidity and thus avoid life-threatening bleeding events from the accidental rupture of an aneurysm. -

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Peripheral arterial disease (Poor blood supply) Information sheet What is it? Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is the narrowing of one or more arteries (blood vessels). It affects arteries that take blood to the legs, reducing the oxygen that gets to the foot that helps keep the tissues healthy. Also known as 'peripheral vascular disease' and sometimes called 'hardening of the arteries'. What causes it? The narrowing of the arteries is caused by atheroma. Atheroma is like fatty patches or 'plaques' that develop inside the lining of arteries. A patch of atheroma starts quite small, and causes no problems at first. Over the years it can thicken up and start to affect the blood flow through the arteries. (It is a bit like limescale that forms on the inside of water pipes). What are the symptoms? The typical symptom is like a ‘cramping’ sensation in the calves when walking a short distance. It is called 'intermittent claudication'. The pain is relieved when you stop walking. In more serious cases, cramp can be felt in the calf muscles during rest and at night. How can I help prevent it? The best way to help prevent this is to: Stop smoking Exercise regularly Maintain a healthy weight Eat a healthy diet Limit the amount of alcohol you drink (Contact your practice nurse for any further advice on the above) Take care of your feet www.oxleas.nhs.uk How do I take care of my feet? Try not to injure your feet as this can lead to an ulcer or infection developing more easily if the blood supply to the feet is reduced. -

Left Atheroma Mass and Occurrence Out-Of-Office Hypertension in an Extensive Population Raimondo Thomas*

Editorial iMedPub Journals Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine and Therapy 2021 www.imedpub.com Vol.4 No.1:e001 Left Atheroma Mass and Occurrence Out-of-Office Hypertension in an Extensive Population Raimondo Thomas* Department of Cardiology, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding author: Thomas R, Department of Cardiology, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 01, 2021; Accepted date: February 15, 2021; Published date: February 22, 2021 Citation: Thomas R (2021) Left Atheroma Mass and Occurrence out- - of Office Hypertension in an Extensive Population. J Cardiovasc Med Ther Vol.4 No.1: e001 supplementation, physical activity, reduced alcohol consumption, and low-fat diets rich in fruits and vegetables have Abstract been effective in lowering BP and avert hypertension. Hypertension is an important risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, and is a major cause Discussion of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Traditionally, The current array of drug and nondrug therapeutic options hypertension diagnosis and treatment and clinical permit for control of hypertension to currently recommended evaluations of antihypertensive efficacy have been based on office blood pressure (BP) measurements; however, there is goal BP levels in all but the rarest patient and supply the increasing evidence that office measures may provide capacity to decrease BP to levels much lower than current inadequate or misleading estimates of a patient’s true BP guidelines recommend. Despite this capability, the vast majority status and level of cardiovascular risk. The introduction, and of patients with hypertension worldwide are untreated or badly endorsement by treatment guidelines, of 24-hour treated. -

SIGN Guideline No 89

89 SIGN Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Diagnosis and management of 89 peripheral arterial disease A national clinical guideline 1 Introduction 1 2 Cardiovascular risk reduction 3 3 Referral, diagnosis and investigation 7 4 Treatment of symptoms 13 5 Follow up 19 6 Information for discussion with patients and carers 21 7 Development of the guideline 23 8 Implementation, audit and resource implications 26 Abbreviations 28 Annexes 29 References 34 October 2006 COPIES OF ALL sign GUIDELINES ARE AVAILABLE ONLINE AT WWW.SIGN.AC.UK KEY to eVIDENCe statements anD graDes of reCOMMENDATIONS LEVels of eVIDENCE 1++ High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), or RCTs with a very low risk of bias 1+ Well conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias 1 - Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias 2++ High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort studies High quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal 2+ Well conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal 2 - Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal 3 Non-analytic studies, eg case reports, case series 4 Expert opinion GRADES OF RECOMMENDATION Note: The grade of recommendation relates to the strength of the evidence on which the recommendation is based. -

Relationship Between Cerebrovascular Atherosclerotic Stenosis and Rupture Risk of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysm a Single-Cen

Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 186 (2019) 105543 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/clineuro Relationship between cerebrovascular atherosclerotic stenosis and rupture risk of unruptured intracranial aneurysm: A single-center retrospective T study Xin Fenga,b, Peng Qia, Lijun Wanga, Jun Lua, Hai Feng Wanga, Junjie Wanga, Shen Hua, Daming Wanga,b,⁎ a Department of Neurosurgery, Beijing Hospital, National Center of Gerontology, No. 1 DaHua Road, Dong Dan, Beijing, 100730, China b Graduate School of Peking Union Medical College, No. 9 Dongdansantiao, Dongcheng District, Beijing, 100730, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Objectives: Cerebrovascular atherosclerotic stenosis (CAS) and intracranial aneurysm (IA) have a common un- Atherosclerotic stenosis derlying arterial pathology and common risk factors, but the clinical significance of CAS in IA rupture (IAR) is Intracranial aneurysm unclear. This study aimed to investigate the effect of CAS on the risk of IAR. Risk factor Patients and methods: A total of 336 patients with 507 sacular IAs admitted at our center were included. Rupture Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association between IAR and the angiographic variables for CAS. We also explored the differences in CAS in patients aged < 65 and ≥65 years. Results: In all the patient groups, moderate (50%–70%) cerebrovascular stenosis was significantly associated with IAR (odds ratio [OR], 3.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.8–6.5). Single cerebral artery stenosis was also significantly associated with IAR (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.3–3.9), and intracranial stenosis may be a risk factor for IAR (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0–3.2). -

SUBARACHNOID HAEMORRHAGE and INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSMS: WHAT NEUROLOGISTS NEED to KNOW I28* P J Kirkpatrick

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.73.suppl_1.i28 on 1 September 2002. Downloaded from SUBARACHNOID HAEMORRHAGE AND INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSMS: WHAT NEUROLOGISTS NEED TO KNOW i28* P J Kirkpatrick J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73(Suppl I):i28–i33 he incidence of stroke caused by subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) remains constant, with intracranial aneurysm rupture causing SAH in up to 5000 patients in the UK per annum. TAlthough this represents less than 5% of all strokes, recognition is of crucial importance since intervention can radically alter outcome. The combined mortality and morbidity for aneurysm rupture reaches 50%; since the condition can affect individuals at any age, long term morbidity in survivors can be substantial.1 Failure to diagnose SAH exposes a patient to the fatal effects of a fur- ther bleed, and also to complications which can now be avoided or successfully treated.23 cPATHOLOGY SAH refers to a leakage of blood into the subarachnoid spaces (fig 1A) which is a continuous space between the supratentorial and infratentorial compartments. A greater concentration of blood products around the site of the bleed is usual, but SAH originating from a focal source can be more diffuse and spread throughout wider aspects of the subarachnoid space. Haemorrhage can extend into adjacent parenchymal structures (fig 1B) and ventricular system, with associated high morbidity and mortality (fig 1C). Inflammatory processes (table 1), excited by the presence of red cell breakdown products, affect copyright. the large vessels of the circle of Willis and smaller vessels within the subpial space.4 These processes are complex, but combine to impair the adequate distribution of blood to affected territories. -

Morphological Variables Associated with Ruptured Basilar Tip Aneurysms Jian Zhang1,2,12, Anil Can1,3,12, Pui Man Rosalind Lai1, Srinivasan Mukundan Jr.4, Victor M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Morphological variables associated with ruptured basilar tip aneurysms Jian Zhang1,2,12, Anil Can1,3,12, Pui Man Rosalind Lai1, Srinivasan Mukundan Jr.4, Victor M. Castro5, Dmitriy Dligach6,7, Sean Finan6, Vivian S. Gainer5, Nancy A. Shadick8, Guergana Savova6, Shawn N. Murphy5,9, Tianxi Cai10, Scott T. Weiss8,11 & Rose Du1,11* Morphological factors of intracranial aneurysms and the surrounding vasculature could afect aneurysm rupture risk in a location specifc manner. Our goal was to identify image-based morphological parameters that correlated with ruptured basilar tip aneurysms. Three-dimensional morphological parameters obtained from CT-angiography (CTA) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA) from 200 patients with basilar tip aneurysms diagnosed at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital between 1990 and 2016 were evaluated. We examined aneurysm wall irregularity, the presence of daughter domes, hypoplastic, aplastic or fetal PCoAs, vertebral dominance, maximum height, perpendicular height, width, neck diameter, aspect and size ratio, height/width ratio, and diameters and angles of surrounding parent and daughter vessels. Univariable and multivariable statistical analyses were performed to determine statistical signifcance. In multivariable analysis, presence of a daughter dome, aspect ratio, and larger fow angle were signifcantly associated with rupture status. We also introduced two new variables, diameter size ratio and parent-daughter angle ratio, which were both signifcantly inversely associated with ruptured basilar tip aneurysms. Notably, multivariable analyses also showed that larger diameter size ratio was associated with higher Hunt-Hess score while smaller fow angle was associated with higher Fisher grade. These easily measurable parameters, including a new parameter that is unlikely to be afected by the formation of the aneurysm, could aid in screening strategies in high-risk patients with basilar tip aneurysms. -

Arterial Thrombosis and Accelerated Atheroma in a Member of a Family with Familial Antithrombin III Deficiency J

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.58.676.108 on 1 February 1982. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (February 1982) 58, 108-109 Arterial thrombosis and accelerated atheroma in a member of a family with familial antithrombin III deficiency J. WINTER D. DONALD B.Sc., M.B., Ch.B., M.R.C.P. M.B., M.R.C.Path. B. BENNETT A. S. DOUGLAS M.D., M.R.C.P. M.D., D.Sc., F.R.C.P. Departments ofMedicine and Pathology, University ofAberdeen, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Foresterhill, Aberdeen AB9 2ZB Summary cigarette smoker. After his death, his mother, 4 of his The case is described of a young man with probable siblings and others in his family were found to have familial antithrombin III deficiency, a disorder ATIII deficiency and have been described previously associated with a marked predisposition to venous (Mackie et al., 1978). thrombo-embolic events. In addition to a history of Protected by copyright. venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, at Post-mortem findings post-mortem this patient demonstrated widespread The upper half of the body was deeply jaundiced, arterial thrombosis and atheroma. The probable the lower half paler. association of severe arterial thrombosis and atheroma Heart: Both ventricles were enlarged, 2 areas of with a clearly definable coagulation disorder pre- healed infarction were present, the mitral valve was disposing to thrombosis is of interest. sclerosed and incompetent, the aortic valve sclerosed and stenosed. Introduction Arteries: There was extensive atheroma of the Antithrombin III (ATIII) is the major physio- aorta and vessels arising from it including the logical inhibitor of the coagulation mechanism coronary arteries.