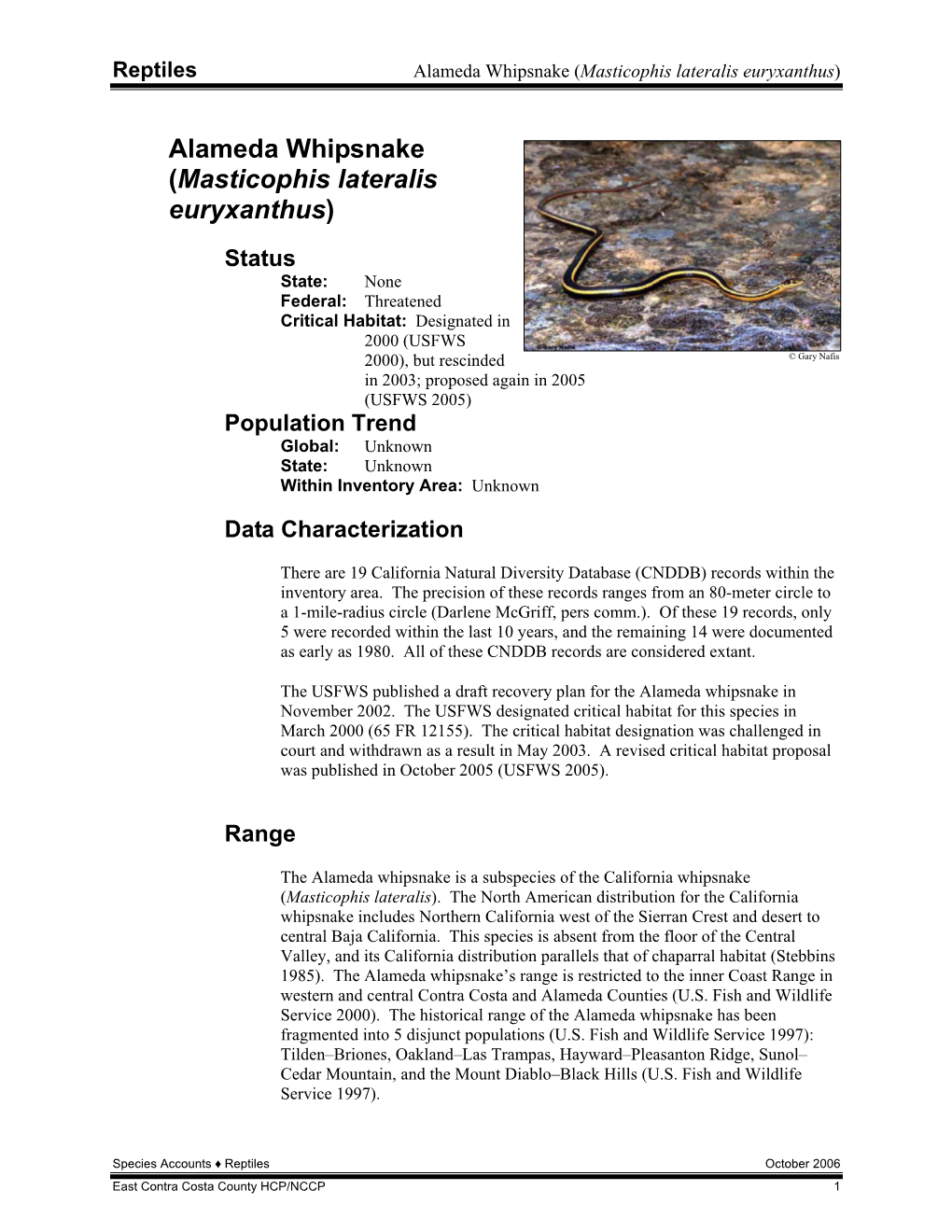

Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Other Contributions

Other Contributions NATURE NOTES Amphibia: Caudata Ambystoma ordinarium. Predation by a Black-necked Gartersnake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis). The Michoacán Stream Salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a facultatively paedomorphic ambystomatid species. Paedomorphic adults and larvae are found in montane streams, while metamorphic adults are terrestrial, remaining near natal streams (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). Streams inhabited by this species are immersed in pine, pine-oak, and fir for- ests in the central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Luna-Vega et al., 2007). All known localities where A. ordinarium has been recorded are situated between the vicinity of Lake Patzcuaro in the north-central portion of the state of Michoacan and Tianguistenco in the western part of the state of México (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). This species is considered Endangered by the IUCN (IUCN, 2015), is protected by the government of Mexico, under the category Pr (special protection) (AmphibiaWeb; accessed 1April 2016), and Wilson et al. (2013) scored it at the upper end of the medium vulnerability level. Data available on the life history and biology of A. ordinarium is restricted to the species description (Taylor, 1940), distribution (Shaffer, 1984; Anderson and Worthington, 1971), diet composition (Alvarado-Díaz et al., 2002), phylogeny (Weisrock et al., 2006) and the effect of habitat quality on diet diversity (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). We did not find predation records on this species in the literature, and in this note we present information on a predation attack on an adult neotenic A. ordinarium by a Thamnophis cyrtopsis. On 13 July 2010 at 1300 h, while conducting an ecological study of A. -

3.4 Biological Resources for the Purpose of This EIR, Biological Resources Comprise Vegetation, Wildlife, Natural Communities, and Wetlands and Other Waters

Impact Analysis Alameda County Community Development Agency Biological Resources 3.4 Biological Resources For the purpose of this EIR, biological resources comprise vegetation, wildlife, natural communities, and wetlands and other waters. Potential biological resource impacts associated with the program and the two individual projects are analyzed. Potential impacts are described quantitatively and qualitatively in Section 3.4.2, Environmental Impacts. This section also identifies specific and detailed measures to avoid, minimize, or compensate for potentially significant impacts on biological resources, where necessary. 3.4.1 Existing Conditions Regulatory Setting Federal Endangered Species Act Pursuant to the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), USFWS and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) have authority over projects that may result in take of a species listed as threatened or endangered under the act. Take is defined under the ESA, in part, as killing, harming, or harassing. Under federal regulations, take is further defined to include habitat modification or degradation that results, or is reasonably expected to result, in death or injury to wildlife by significantly impairing essential behavioral patterns, including breeding, feeding, or sheltering. If a likelihood exists that a project would result in take of a federally listed species, either an incidental take permit, under Section 10(a) of the ESA, or a federal interagency consultation, under Section 7 of the ESA, is required. Several federally listed species—vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi), longhorn fairy shrimp (Branchinecta longiantenna), vernal pool tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus packardi), California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense), California red‐legged frog (Rana draytonii), Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus), and San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica)—have the potential to be affected by activities associated with the Golden Hills and Patterson Pass projects as well as subsequent repowering projects. -

Biological Resources Assessment

Biological Resources Assessment Valle Vista Properties HAYWARD, ALAMEDA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared For: William Lyon Homes, Inc. 2603 Camino Ramon, Suite 450 San Ramon, California 94583 Contact: Scott Roylance WRA Contact: Mark Kalnins [email protected] Date: July 10, 2017 Revised: November 16, 2017 2169-G East Francisco Blvd., San Rafael, CA 94702 (415) 454-8868 tel [email protected] www.wra-ca.com This page intentionally blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 REGULATORY BACKGROUND ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 Sensitive Biological Communities .............................................................................. 3 2.2 Special-Status Species .............................................................................................. 8 2.3 Relevant Local Policies, Ordinances, Regulations ..................................................... 9 3.0 METHODS ............................................................................................................................. 9 3.1 Biological Communities ............................................................................................ 10 3.1.1 Non-Sensitive Biological Communities ...................................................... 10 3.1.2 Sensitive Biological Communities .............................................................. 10 3.2 Special-Status Species ........................................................................................... -

Alameda Whipsnake: the Fasttest Snake in the West by Mike Westphal

Alameda Whipsnake: The Fasttest Snake in the West by Mike Westphal A narrow footpath circles the crest of Mt. Diablo. The sunlight comes early to this high place and in May will warm the rocky soil around the manzanita bushes early in the morning, once the fog has burned away. If you were a snake - a fast snake, a snake that hunted lizards by day - you would live in a place like this, a place among the shrubbery where you could heat up and go. If you, on the other hand, up and go. If you, on the other hand, were a person and Photo by Sheila Larsen / USFWS wanted to pay a call on the Alameda whipsnake, you might also come here. A simple wooden rail follows the footpath on the downhill side. Walk slowly along the rail and watch the ground. Be quiet and alert. The Alameda whipsnake does not wait. If it sees you and doesn’t want to hang around, it will be gone before you even know what you’re looking at. If you are careful enough, you may see a rare and beautiful snake - a snake built for speed. Its body is long (to six feet) annd whiplike (hence the name). The neck is slender, topped with a darting head that houses the big eyes of a visual predator. In color, it is the deep, deep green traditional to British racecars; it is detailed on either side with a bold orange stripe. The whipsnake is polished and glossy in the morning sun. Stare at it as long as you can, for this is no "sit-and-wait" predator, and will soon move away to chase down a fat lizard for breakfast. -

Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus)

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 192 / Tuesday, October 3, 2000 / Rules and Regulations 58933 EFFECTIVE DATE: October 1, 2000. PART 1837ÐSERVICE CONTRACTING Alameda whipsnakes range from 91 to FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: 122 centimeters (3 to 4 feet) in length. James H. Dolvin, NASA Headquarters, 2. Subpart 1837.70 is removed. The dorsal surface is sooty black in Office of Procurement, Contract [FR Doc. 00±25249 Filed 10±2±00; 8:45 am] color with a distinct yellow-orange Management Division (Code HK), BILLING CODE 7510±01±M stripe down each side. The forward Washington, DC 20546. (202) 358±1279, portion of the bottom surface is orange- email: [email protected]. rufous colored, the midsection is cream colored, and the rear portion and tail are SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR pinkish. The adult Alameda whipsnake A. Background Fish and Wildlife Service virtually lacks black spotting on the In 1991, Subpart 1837.70, Acquisition bottom surface of the head and neck. of Training, was added to the NFS. 50 CFR Part 17 Juveniles may show very sparse or weak black spots. Another common name for Section 1837.7000, Acquisition of off- RIN 1018±AF98 the-shelf training courses, provided that the Alameda whipsnake is the ``Alameda striped racer'' (Riemer 1954, the Government Employees Training Endangered and Threatened Wildlife Act of 1958, 5 U.S.C. 4101 et seq., could Jennings 1983, Stebbins 1985). and Plants; Final Determination of The Alameda whipsnake is one of two be used as the authority for acquisition Critical Habitat for the Alameda subspecies of the California whipsnake of ``non-Governmental off-the-shelf Whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis (Masticophis lateralis). -

Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus) 5-Year

Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Photograph by Sheila Larson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office Sacramento, California September 2011 5-YEAR REVIEW Alameda whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5-year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species, be changed in status from endangered to threatened, be changed in status from threatened to endangered, or that the status remain unchanged. Our original listing of a species as endangered or threatened is based on the existence of threats attributable to one or more of the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act, and we must consider these same five factors in any subsequent consideration of reclassification or delisting of a species. In the 5-year review, we consider the best available scientific and commercial data on the species, and focus on new information available since the species was listed or last reviewed. If we recommend a change in listing status based on the results of the 5-year review, we must propose to do so through a separate rule-making process defined in the Act that includes public review and comment. -

Reptiles and Amphibians of Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Belize

Reptiles and Amphibians of the Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk District, Belize Ryan L. Lynch, Mike Rochford, Laura A. Brandt and Frank J. Mazzotti University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center; 3205 College Avenue; Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 All pictures taken by RLL: [email protected] and MR: [email protected] Vaillant’s Frog Rio Grande Leopard Frog Common Mexican Treefrog Rana vaillanti Rana berlandieri Smilisca baudinii Veined Treefrog Red Eyed Treefrog Stauffer’s Treefrog Phrynohyas venulosa Agalychnis callidryas Scinax staufferi White-lipped Frog Fringe-toed Foam Frog Fringe-toed Foam Frog Leptodactylus labialis Leptodactylus melanonotus Leptodactylus melanonotus 1 Reptiles and Amphibians of the Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk District, Belize Ryan L. Lynch, Mike Rochford, Laura A. Brandt and Frank J. Mazzotti University of Florida, Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center; 3205 College Avenue; Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314 All pictures taken by RLL: [email protected] and MR: [email protected] Tungara Frog Marine Toad Gulf Coast Toad Physalaemus pustulosus Bufo marinus Bufo valliceps Sheep Toad House Gecko Dwarf Bark Gecko Hypopachus variolosus Hemidactylus frenatus Shaerodactylus millepunctatus Turnip-tailed Gecko Yucatan Banded Gecko Yucatan Banded Gecko Thecadactylus rapicaudus Coleonyx elegans Coleonyx elegans 2 Reptiles and Amphibians of the Lamanai Outpost Lodge, Orange Walk District, Belize Ryan L. Lynch, Mike Rochford, Laura A. Brandt and Frank J. Mazzotti University -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 234 / Friday, December 5, 1997 / Rules and Regulations

64306 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 234 / Friday, December 5, 1997 / Rules and Regulations Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306; E.O. SUBCHAPTER TÐSMALL PART 177ÐCONSTRUCTION AND 12234, 45 FR 58801, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. PASSENGER VESSELS (UNDER 100 ARRANGEMENT 277; 49 CFR 1.46. GROSS TONS) 20. The authority citation for part 177 § 121.710 [Corrected] continues to read as follows: PART 175ÐGENERAL PROVISIONS 15. In § 121.710, remove the words Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306; E.O. ``part 160, subpart 160.041, of this 18. The authority citation for part 175 12234, 45 FR 58801, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. chapter'' and add, in their place, the 277; 49 CFR 1.46. words ``approval series 160.041''. continues to read as follows: 21. In § 177.500, in paragraph (j)(1), Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306; 49 U.S.C. remove the last word ``and'' and add, in PART 122ÐOPERATIONS App. 1804; 49 CFR 1.45, 1.46. Sec. 175.900 its place, the word ``or''; and revise also issued under 44 U.S.C. 3507. 16. The authority citation for part 122 paragraph (o)(1) to read as follows: continues to read as follows: 19. In § 175.400, in the definition for § 177.500 Means of escape. Authority: 46 U.S.C. 2103, 3306, 6101; E.O. ``High Speed Craft'', in the equation ``V 12234, 45 FR 58801, 3 CFR, 1980 Comp., p. = 3.7 × displ 1667 h'', add a decimal point * * * * * 277; 49 CFR 1.46. (o) * * * before the number ``1667'', and add, in (1) The space has a deck area less than § 122.604 [Corrected] alphabetical order, a definition for 30 square meters (322 square feet); ``wood vessel'' to read as follows: 17. -

Conservation Genetics of the Imperiled Striped Whipsnake in Washington, USA

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 15(3):597–610. Submitted: 9 March 2020; Accepted: 5 November 2020; Published: 16 December 2020. CONSERVATION GENETICS OF THE IMPERILED STRIPED WHIPSNAKE IN WASHINGTON, USA DAVID S. PILLIOD1,4, LISA A. HALLOCK2, MARK P. MILLER3, THOMAS D. MULLINS3, AND SUSAN M. HAIG3 1U.S. Geological Survey, Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 970 Lusk Street, Boise, Idaho 83706, USA 2Wildlife Program, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 1111 Washington Street, Olympia, Washington 98504, USA 3U.S. Geological Survey, Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 3200 Southwest Jefferson Way, Corvallis, Oregon 97331, USA 4Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Conservation of wide-ranging species is aided by population genetic information that provides insights into adaptive potential, population size, interpopulation connectivity, and even extinction risk in portions of a species range. The Striped Whipsnake (Masticophis taeniatus) occurs across 11 western U.S. states and into Mexico but has experienced population declines in parts of its range, particularly in the state of Washington. We analyzed nuclear and mitochondrial DNA extracted from 192 shed skins, 63 muscle tissue samples, and one mouth swab to assess local genetic diversity and differentiation within and between the last known whipsnake populations in Washington. We then placed that information in a regional context to better understand levels of differentiation and diversity among whipsnake populations in the northwestern portion of the range of the species. Microsatellite data analyses indicated that there was comparable genetic diversity between the two extant Washington populations, but gene flow may be somewhat limited. We found moderate to high levels of genetic differentiation among states across all markers, including five microsatellites, two nuclear genes, and two mitochondrial genes. -

Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis Lateralis Euryxanthus)

Reptiles Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) Alameda Whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus) Status State: None Federal: Threatened Critical Habitat: Designated in 2000 (USFWS 2000), but rescinded © Gary Nafis in 2003 Population Trend Global: Unknown State: Unknown Within Inventory Area: Unknown Data Characterization There are 19 California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB) records within the inventory area. The precision of these records ranges from an 80-meter circle to a 1-mile-radius circle (Darlene McGriff pers comm.). Of these 19 records, only 5 were recorded within the last 10 years, and the remaining 14 were documented as early as 1980. All of these CNDDB records are considered extant. The USFWS published a draft recovery plan for the Alameda whipsnake in November 2002. The USFWS designated critical habitat for this species in March 2000 (65 FR 12155). The critical habitat designation was challenged in court and withdrawn as a result in May 2003. Range The Alameda whipsnake is a subspecies of the California whipsnake (Masticophis lateralis). The North American distribution for the California whipsnake includes Northern California west of the Sierran Crest and desert to central Baja California. This species is absent from the floor of the Central Valley, and its California distribution parallels that of chaparral habitat (Stebbins 1985). The Alameda whipsnake’s range is restricted to the inner Coast Range in western and central Contra Costa and Alameda Counties (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2000). The historical range of the Alameda whipsnake has been fragmented into 5 disjunct populations (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1997): Tilden–Briones, Oakland–Las Trampas, Hayward–Pleasanton Ridge, Sunol– Cedar Mountain, and the Mount Diablo–Black Hills (U.S. -

Alameda Striped Racer Presentation

Welcome to the Conservation Lecture Series www.dfg.ca.gov/habcon/lectures Questions? Contact [email protected] Ecology and Conservation of the Alameda Striped Racer (=Alameda Whipsnake) Overview: Description & Status Distribution & Critical Habitat Field Study Methods (1989-2013) Findings: Taxonomy and Potential Refinement of Distribution Taxonomy Masticophis lateralis - (Hallowell, 1853) – Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 237 Masticophis lateralis euryxanthus - (Riemer, 1954) - Copeia 1954 (1): 45-48p. Now: Coluber lateralis euryxanthus Two Subspecies of California Striped Racer © Gary Nafis Alameda Striped Racer Chaparral Striped Racer (Coluber lateralis euryxanthus) (Coluber lateralis lateralis) • Slender body, fast moving, diurnal • Large head and eyes • Adults up to 5 feet total length • Relatively large hatchlings- • Alameda Striped Racer (Coluber lateralis euryxanthus) • State Threatened (1971) and Federally Threatened (1997) • Subspecies of California Striped Racer Alameda Striped Racer Range: Alameda and Contra Costa Counties???????? • Characters Described by Riemer in 1954 • All of the 8 differences between subspecies are color characteristics Alameda Whipsnake AWS Distribution and Critical Habitat California Whipsnake Distribution in Contra Costa, Alameda and Northern Santa Clara Counties AWS Critical Habitat Field Study Methods Trapping Surveys • Drift fences with funnel traps at each end. • Traps constructed of large hardware cloth panels on a wooden frame for air circulation. • Foam refugia are -

Sexual Dimorphism, Reproductive Biology, and Dietary Habits of Psammophiine Snakes (Colubridae) from Southern Africa Author(S): Richard Shine, William R

Sexual Dimorphism, Reproductive Biology, and Dietary Habits of Psammophiine Snakes (Colubridae) from Southern Africa Author(s): Richard Shine, William R. Branch, Jonathan K. Webb, Peter S. Harlow, and Terri Shine Source: Copeia, 2006(4):650-664. 2006. Published By: The American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1643/0045-8511(2006)6[650:SDRBAD]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/ full/10.1643/0045-8511%282006%296%5B650%3ASDRBAD%5D2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Copeia, 2006(4), pp. 650–664 Sexual Dimorphism, Reproductive Biology, and Dietary Habits of Psammophiine Snakes (Colubridae) from Southern Africa RICHARD SHINE,WILLIAM R. BRANCH,JONATHAN K. WEBB,PETER S. HARLOW, AND TERRI SHINE Slender-bodied, diurnal ‘‘sand snakes’’ of the genus Psammophis are widespread and abundant through Africa, but the general biology of these animals remains poorly known.