Lynching Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Granite Mansion: Georgia's Governor's Mansion 1924-1967

The Granite Mansion: Georgia’s Governor’s Mansion 1924-1967 Documentation for the proposed Georgia Historical Marker to be installed on the north side of the road by the site of the former 205 The Prado, Ansley Park, Atlanta, Georgia June 2, 2016 Atlanta Preservation & Planning Services, LLC Georgia Historical Marker Documentation Page 1. Proposed marker text 3 2. History 4 3. Appendices 10 4. Bibliography 25 5. Supporting images 29 6. Atlanta map section and photos of proposed marker site 31 2 Proposed marker text: The Granite Governor’s Mansion The Granite Mansion served as Georgia’s third Executive Mansion from 1924-1967. Designed by architect A. Ten Eyck Brown, the house at 205 The Prado was built in 1910 from locally- quarried granite in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. It was first home to real estate developer Edwin P. Ansley, founder of Ansley Park, Atlanta’s first automobile suburb. Ellis Arnall, one of the state’s most progressive governors, resided there (1943-47). He was a disputant in the infamous “three governors controversy.” For forty-three years, the mansion was home to twelve governors, until poor maintenance made it nearly uninhabitable. A new governor’s mansion was constructed on West Paces Ferry Road. The granite mansion was razed in 1969, but its garage was converted to a residence. 3 Historical Documentation of the Granite Mansion Edwin P. Ansley Edwin Percival Ansley (see Appendix 1) was born in Augusta, GA, on March 30, 1866. In 1871, the family moved to the Atlanta area. Edwin studied law at the University of Georgia, and was an attorney in the Atlanta law firm Calhoun, King & Spalding. -

Study Guide for the Georgia History Exemption Exam Below Are 99 Entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Available At

Study guide for the Georgia History exemption exam Below are 99 entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (available at www.georgiaencyclopedia.org. Students who become familiar with these entries should be able to pass the Georgia history exam: 1. Georgia History: Overview 2. Mississippian Period: Overview 3. Hernando de Soto in Georgia 4. Spanish Missions 5. James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) 6. Yamacraw Indians 7. Malcontents 8. Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739) 9. Royal Georgia, 1752-1776 10. Battle of Bloody Marsh 11. James Wright (1716-1785) 12. Salzburgers 13. Rice 14. Revolutionary War in Georgia 15. Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) 16. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) 17. Mary Musgrove (ca. 1700-ca. 1763) 18. Yazoo Land Fraud 19. Major Ridge (ca. 1771-1839) 20. Eli Whitney in Georgia 21. Nancy Hart (ca. 1735-1830) 22. Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia 23. War of 1812 and Georgia 24. Cherokee Removal 25. Gold Rush 26. Cotton 27. William Harris Crawford (1772-1834) 28. John Ross (1790-1866) 29. Wilson Lumpkin (1783-1870) 30. Sequoyah (ca. 1770-ca. 1840) 31. Howell Cobb (1815-1868) 32. Robert Toombs (1810-1885) 33. Alexander Stephens (1812-1883) 34. Crawford Long (1815-1878) 35. William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891) 36. Mark Anthony Cooper (1800-1885) 37. Roswell King (1765-1844) 38. Land Lottery System 39. Cherokee Removal 40. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) 41. Georgia in 1860 42. Georgia and the Sectional Crisis 43. Battle of Kennesaw Mountain 44. Sherman's March to the Sea 45. Deportation of Roswell Mill Women 46. Atlanta Campaign 47. Unionists 48. Joseph E. -

The Attorney General's Ninth Annual Report to Congress Pursuant to The

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S NINTH ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACT OF 2007 AND THIRD ANNUALREPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVEDCIVIL RIGHTS CRIMES REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2016 March 1, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is the ninth annual Report (Report) submitted to Congress pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of2007 (Till Act or Act), 1 as well as the third Report submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016 (Reauthorization Act). 2 This Report includes information about the Department of Justice's (Department) activities in the time period since the eighth Till Act Report, and second Reauthorization Report, which was dated June 2019. Section I of this Report summarizes the historical efforts of the Department to prosecute cases involving racial violence and describes the genesis of its Cold Case Int~~ative. It also provides an overview ofthe factual and legal challenges that federal prosecutors face in their "efforts to secure justice in unsolved Civil Rights-era homicides. Section II ofthe Report presents the progress made since the last Report. It includes a chart ofthe progress made on cases reported under the initial Till Act and under the Reauthorization Act. Section III of the Report provides a brief overview of the cases the Department has closed or referred for preliminary investigation since its last Report. Case closing memoranda written by Department attorneys are available on the Department's website: https://www.justice.gov/crt/civil-rights-division-emmett till-act-cold-ca e-clo ing-memoranda. -

Read Our Full Report, Death in Florida, Now

USA DEATH IN FLORIDA GOVERNOR REMOVES PROSECUTOR FOR NOT SEEKING DEATH SENTENCES; FIRST EXECUTION IN 18 MONTHS LOOMS Amnesty International Publications First published on 21 August 2017 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2017 Index: AMR 51/6736/2017 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 ‘Bold, positive change’ not allowed ................................................................................ -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

Commencement

WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY Commencement THE GRADUATION EXERCISES MONDAY, MAY THE TWENTY-FIRST TwO THOUSAND AND TWELVE T HE GRADU A T ION EXE R C ISE S MONDAY, MAY THE TWEN T YFIRST TWO THO U SAND AND TWEL VE N INE O’C LOCK IN THE M ORNING T H O M AS K. HE ARN, JR. PLAZA THE CARILLON: “Preludium VII” ....................................................... Matthias Van den Gheyn Lauren Bradley Mellick (’05), University Carillonneur THE PROCESSIONAL ....................................................................e Brass Ensemble THE WELCOME ........................................................................... Nathan O. Hatch President GREETINGS FROM THE CLASS OF 2012 ..................................................Nilam A. Patel (’12) Student Body President THE PRAYER OF INVOCATION ..............................................e Reverend Timothy L. Auman University Chaplain THE ADDRESS: “A Little Fatherly Advice” .....................................................Charles W. Ergen Chairman, DISH Network and EchoStar Communications THE CONFERRING OF HONORARY DEGREES ..................................................Mark E. Welker Interim Provost Charles W. Ergen, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Bernard Beatty, Associate Professor of Management, Schools of Business Elizabeth B. Lacy, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Blake Morant, Dean, School of Law Willie E. May, Doctor of Science Sponsor: Lorna Moore, Dean, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Jonathan T.M. Reckford, Doctor of Humane Letters Sponsor: Julie Wayne, Associate Professor, Schools of Business Eric C. Wiseman, Doctor of Laws Sponsor: Steve Reinemund, Dean, Schools of Business REMARKS TO THE GRADUATES ............................................................President Hatch THE HONORING OF RETIRING FACULTY FROM THE BOWMAN GRAY CAMPUS Patricia L. Adams, M.D., Professor Emerita of Internal Medicine - Nephrology Vardaman M. Buckalew, Jr., M.D., Professor Emeritus of Internal Medicine - Nephrology John R. Crouse III, M.D., Professor Emeritus of Internal Medicine - Endocrinology and Metabolism Robert G. -

Badges of Slavery : the Struggle Between Civil Rights and Federalism During Reconstruction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction. Vanessa Hahn Lierley 1981- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lierley, Vanessa Hahn 1981-, "Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 831. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/831 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Liedey B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2013 BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Lierley B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Approved on April 19, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Benjamin Harrison Jasmine Farrier ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband Pete Lierley who always showed me support throughout the pursuit of my Master's degree. -

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr

Harold Paulk Henderson, Sr. Oral History Collection OH Vandiver 23 George Dekle Busbee Interviewed by Dr. Harold Paulk Henderson Date: 03-17-94 Cassette # 474 (26 Minutes, Side One Only) EDITED BY DR. HENDERSON Side One Henderson: This is an interview with former Governor George D. [Dekle] Busbee in his law office in Atlanta. The date is March 17, 1994. I am Dr. Hal Henderson. Good afternoon, Governor Busbee. Busbee: Good day. Henderson: Thank you very much for granting me this interview. Busbee: I'm delighted. Henderson: You served in the state House of Representatives the last two years of the [Samuel] Marvin Griffin [Sr.] administration and you served all four years of [Samuel] Ernest Vandiver's [Jr.] administration. Let me begin by asking you: what was your impression of the Marvin Griffin administration? Busbee: Well, of course, if you had to choose sides Marvin wouldn't have said that I was in his camp. I will say, however, that I was reminiscing with some people that served in the legislature with me back then and have served since I was governor, and we don't think it's as much fun as it used to be. I think he was a very colorful character and we had a great time, but I think that was former days for Georgia; that's not the era that we're in now. Henderson: Okay. How would you describe the relationship between Lieutenant Governor Vandiver and Governor Marvin Griffin? 2 Busbee: Well, the first real bitter fight that I became engaged in as a legislator was during the time that I was there [and] Marvin Griffin was governor, and we had the rural roads fight. -

Hugh M. Gillis Papers

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Finding Aids 1995 Hugh M. Gillis papers Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids Part of the American Politics Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Zach S. Henderson Library. Georgia Southern University, "Hugh M. Gillis papers" (1995). Finding Aids. 10. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/finding-aids/10 This finding aid is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUGH M. GILLIS PAPERS FINDING AID OVERVIEW OF COLLECTION Title: Hugh M. Gillis papers Date: 1957-1995 Extent: 1 Box Creator: Gillis, Hugh M., 1918-2013 Language: English Repository: Zach S. Henderson Library Special Collections, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA. [email protected]. 912-478-7819. library.georgiasouthern.edu. Processing Note: Finding aid revised in 2020. INFORMATION FOR USE OF COLLECTION Conditions Governing Access: The collection is open for research use. Physical Access: Materials must be viewed in the Special Collections Reading Room under the supervision of Special Collections staff. Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use: In order to protect the materials from inadvertent damage, all reproduction services are performed by the Special Collections staff. All requests for reproduction must be submitted using the Reproduction Request Form. Requests to publish from the collection must be submitted using the Publication Request Form. Special Collections does not claim to control the rights to all materials in its collection. -

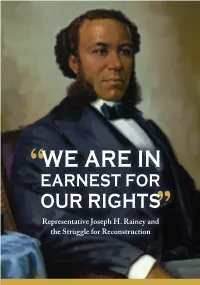

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

Exploring the Black Wombman's Sphere and the Anti-Lynching Crusade of the Early Twentieth Century Deleso Alford Washington [email protected]

Florida A&M University College of Law Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law Journal Publications Faculty Works Summer 2006 Exploring the Black Wombman's Sphere and the Anti-Lynching Crusade of the Early Twentieth Century Deleso Alford Washington [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.law.famu.edu/faculty-research Recommended Citation Washington, Deleso Alford, Exploring the Black Wombman's Sphere and the Anti-Lynching Crusade of the Early Twentieth Century, 3 Geo. J. Gender & L. 895 (2002) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE BLACK WOMBMAN'S SPHERE AND IE, AN I LYNCHING CRUSADE OF THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY DELESO ALFORD WASHINGTON* This paper will explore the black' wombman's intersection ' of race, class, and sex during the early twentieth century, specifically as it relates to the pursuit of federal anti-lynching legislation. The black wombman's sphere is self-defining, in that she is "bone black" 3 with a womb, having the ability to create and protect life, both biologically and figuratively. My central focus will be on the courageous efforts of black women to protect life by virtue of nommo,4 which means power of the spoken word. The black wombman's nommo created a unique sphere, unlike the "woman's sphere" at the dawn of the nineteenth womanhood, the ideal woman was seen not century, which "in the cult of true 5 only as submissive but also gentle, innocent, pure, modest, and pious." However, the stark realities of the multidimensional impact of racism, sexism and classism imposed upon the black wombman did not afford her the status of an 'ideal woman,' thus the black wombman defined her own sphere.