Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Myth of Portlandia

Portland State University PDXScholar Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Publications Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Winter 2013 The Myth of Portlandia Sara Gates Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/metropolitianstudies Part of the Television Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Gates, S. (2013) The Myth of Portlandia. Winter 2013 Metroscape, p. 24-29. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Publications by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Myth of Portlandia Portlandia, Grimm, Leverage An interview with Carl Abbott and Karin Magaldi by Sara Gates arl Abbott is a professor of Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State C University and a local expert on the intertwining relationships between the growth, urbanization, and cultural evolutions of cities. Since beginning his tenure at PSU in 1978, Dr. Abbott has published numerous books on Portland itself, as well as the urbanization of the American West; his most recent is Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People (2011). Karin Magaldi is the department chair of Theatre & Film at PSU, with extensive experience in teaching screenwriting and production. In addition to directing several PSU departmental productions, she has also worked with local theatre groups including Portland Center Stage, Third Rail Repertory, and Artists Repertory Theatre. Recently, Metroscape writer Sara Gates sat down with Dr. -

Film Financing

2017 An Outsider’s Glimpse into Filmmaking AN EXPLORATION ON RECENT OREGON FILM & TV PROJECTS BY THEO FRIEDMAN ! ! Page | !1 Contents Tracktown (2016) .......................................................................................................................6 The Benefits of Gusbandry (2016- ) .........................................................................................8 Portlandia (2011- ) .....................................................................................................................9 The Haunting of Sunshine Girl (2010- ) ...................................................................................10 Green Room (2015) & I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore (2017) ...........................11 Network & Experience ............................................................................................................12 Financing .................................................................................................................................12 Filming ....................................................................................................................................13 Distribution ...............................................................................................................................13 In Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................13 Financing Terms .....................................................................................................................15 -

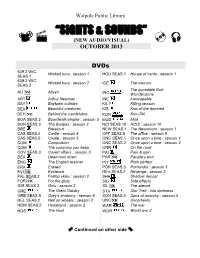

New Audio/Visual) October 2013

Walpole Public Library “SIGHTS & SOUNDS” (NEW AUDIO/VISUAL) OCTOBER 2013 DVDs 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 1 HOU SEAS.1 House of cards : season 1 SEAS.1 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 2 ICE The iceman SEAS.2 The incredible Burt ALI NR Aliyah INC Wonderstone ART Arthur Newman INE Inescapable BAY Baytown outlaws KIL Killing season BEA Beautiful creatures KIS Kiss of the damned BEH NR Behind the candelabra KON Kon-Tiki BOA SEAS.3 Boardwalk empire : season 3 MUD Mud BOR SEAS.3 The Borgias : season 3 NCI SEAS.10 NCIS : season 10 BRE Breakout NEW SEAS.1 The Newsroom : season 1 CAS SEAS.4 Castle : season 4 OFF SEAS.9 The office : season 9 CAS SEAS.5 Castle : season 5 ONC SEAS.1 Once upon a time : season 1 COM Compulsion ONC SEAS.2 Once upon a time : season 2 COM The company you keep ONR On the road COV SEAS.3 Covert affairs : season 3 PAI Pain & gain DEA Dead man down PAR NR Parade’s end ENG The English teacher PIT Pitch perfect ERA Erased POR SEAS.3 Portlandia : season 3 EVI NR Evidence REV SEAS.2 Revenge : season 2 FAL SEAS.2 Falling skies : season 2 SHA Shadow dancer FOR NR For the glory SID Side effects GIR SEAS.2 Girls : season 2 SIL NR The silence GRE The Great Gatsby STA Star Trek : into darkness GRE SEAS.9 Grey’s anatomy : season 9 SON SEAS.5 Sons of anarchy : season 5 HEL SEAS.2 Hell on wheels : season 2 UNC NR Uncertainty HOM SEAS.2 Homeland : season 2 WAR The war HOS The Host WOR World war Z Continued on other side 2 Walpole Public Library NEW AUDIO/VISUAL 2013 Books on CD Manson : the life and Refusal 364.1523 MAN times of -

BRYCE FORTNER Director of Photography Brycefortner.Com

BRYCE FORTNER Director of Photography brycefortner.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS A MILLION LITTLE THINGS James Griffiths KAPITAL ENTERTAINMENT / ABC Pilot & Season 4 Various Directors Chris Smirnoff, DJ Nash Aaron Kaplan STARGIRL 2 Julia Hart GOTHAM GROUP / DISNEY+ Feature Film Nathan Kelly, Jordan Horowitz Ellen Goldsmith-Vein HELLO, GOODBYE AND EVERYTHING Michael Lewen ACE ENTERTAINMENT IN BETWEEN Feature Film Chris Foss, Max Siemers I’M YOUR WOMAN Julia Hart AMAZON Feature Film Jordan Horowitz, Rachel Brosnahan STARGIRL Julia Hart GOTHAM GROUP / PRINCIPAL DISNEY Feature Film Jim Powers, Jordan Horowitz DOLLFACE Matt Spicer ABC SIGNATURE / HULU Pilot Melanie Elin, Stephanie Laing BROKEN DIAMONDS Peter Sattler BLACK LABEL Feature Film Ellen Schwartz, Mary Sparacio THE MAYOR James Griffiths ABC Pilot Scott Printz, Jean Hester PROFESSOR MARSTON & THE Angela Robinson SONY WONDER WOMEN Terry Leonard, Amy Redford Feature Film Andrea Sperling, Jill Soloway THE TICK Wally Pfister SONY / AMAZON Pilot Kerry Orent, Barry Josephson INGRID GOES WEST Feature Film Matt Spicer STAR THROWER ENTERTAINMENT Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival Jared Goldman HOUSE OF CARDS Wally Pfister NETFLIX Season 4 Promos CHARITY CASE James Griffiths ABC / FOX Pilot Scott Printz, Thea Mann PUNCHING HENRY Feature Film Gregori Viens Ian Coyne, David Permut Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival FLAKED Wally Pfister NETFLIX Series Josh Gordon Tiffany Moore, Mitch Hurwitz Will Arnett TOO LEGIT Short Frankie Shaw Liz Destro Official Selection, -

The Dead Don't Die — They Rise from Their Graves and Savagely Attack and Feast on the Living, and the Citizens of the Town Must Battle for Their Survival

THE DEAD DON’T DIE The Greatest Zombie Cast Ever Disassembled Bill Murray ~ Cliff Robertson Adam Driver ~ Ronnie Peterson Tilda Swinton ~ Zelda Wintson Chloë Sevigny ~ Mindy Morrison Steve Buscemi ~ Farmer Miller Danny Glover ~ Hank Thompson Caleb Landry Jones ~ Bobby Wiggins Rosie Perez ~ Posie Juarez Iggy Pop ~ Coffee Zombie Sara Driver ~ Coffee Zombie RZA ~ Dean Carol Kane ~ Mallory O’Brien Austin Butler ~ Jack Luka Sabbat ~ Zach Selena Gomez ~ Zoe and Tom Waits ~ Hermit Bob The Filmmakers Written and Directed by Jim Jarmusch Produced by Joshua Astrachan Carter Logan TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Synopsis . 4 II. “The Dead Don’t Die” Music and Lyrics by Sturgill Simpson 5 III. About the Production . 6 IV. Zombie Apocalypse Now . 8 V. State of the Nation . 11 VI. A Family Affair . 15 VII. Day For Night . 18 VIII. Bringing the Undead to Life . 20 IX. Anatomy of a Scene: Coffee! . 23 X. A Flurry of Zombies . 27 XI. Finding Centerville . 29 XII. Ghosts Inside a Dream . 31 XIII. About the Filmmaker – Jim Jarmusch . 33 XIV. About the Cast . 33 XV. About the Filmmakers . 49 XVI. Credits . 54 2 SYNOPSIS In the sleepy small town of Centerville, something is not quite right. The moon hangs large and low in the sky, the hours of daylight are becoming unpredictable, and animals are beginning to exhibit unusual behaviors. No one quite knows why. News reports are scary and scientists are concerned. But no one foresees the strangest and most dangerous repercussion that will soon start plaguing Centerville: The Dead Don't Die — they rise from their graves and savagely attack and feast on the living, and the citizens of the town must battle for their survival. -

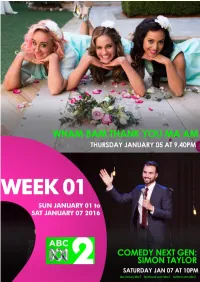

ABC2 Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABC2 Program Guide: National: Week 1 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 1 January 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Monday, 2 January 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Tuesday, 3 January 2017 ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Wednesday, 4 January 2017 ............................................................................................................................... 18 Thursday, 5 January 2017 ................................................................................................................................... 23 Friday, 6 January 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 29 Saturday, 7 January 2017 .................................................................................................................................... 35 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 41 2 | P a g e ABC2 Program Guide: -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

The Oregonian Opinion: a Building Too Weird for Even Portlandia

The Oregonian Opinion: A building too weird for even Portlandia By David Sarasohn So to all the other dismal aspects of the Portland Building, we can now add a new one: a $95 million estimate for repairs. It’s not hard to imagine why the price is so high. Looking at the building, you’d wonder where in the universe the contractors would get parts. The Portland Building, after all, doesn’t really look like anything else. All huge blue tiles, colored glass and odd pastel flourishes meant to evoke early modern French paintings, it’s always looked like something designed by a Third World dictator’s mistress’s art-student brother, setting off an upheaval in the palace, and possibly a revolution. A few years ago, it comfortably made it onto Travel + Leisure magazine’s list of theugliest buildings in the world, closely following a tourist hotel in North Korea and the Ohio headquarters of a picnic basket company, a building shaped like – yes – a picnic basket. To try to humanize the building, the city affixed to the front of it a huge two-story statue of Portlandia, a figure locals had never known existed – unless personal legal problems had given them lots of occasions to study the city seal – but who quickly became popular, eventually getting her own TV show. Portlandia became so popular, in fact, that Portlanders swiftly began proposing to move her someplace else. (This has been an awkward situation for Portlandia herself. Reportedly, it has taken several interventions by city labor negotiators to keep her from walking off the building.) The Portland Building was a product of what might be called the city’s Paleo Cool stage, the early ‘80s, when Portland was just switching from lumber to lattes, beginning to think it might actually have a unique identity. -

Love Is Strange. 04

Love is strange. 04 14. BILL HADER 18. GUEST STAR SIMON RICH 14. EXECUTIVE PRODUCER | CREATOR MICHAEL HOGAN GUEST STAR 19. 14. LORNE MICHAELS VANESSA BAYER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR 20. 07 14. ANDREW SINGER MINKA KELLY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR 20. 15. JONATHAN KRISEL FRED ARMISEN EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR | DIRECTOR 15. 21. RAEANNA GUITARD IAN MAXTONE - GRAHAM GUEST STAR CO - EXECUTIVE PRODUCER | WRITER 08 15. OKSANA BAIUL 21. GUEST STAR ROBERT PADNICK CO - PRODUCER 15. | WRITER MATT LUCAS GUEST STAR 22. DAN MIRK STAFF WRITER 22. SOFIA ALVAREZ 11 STAFF WRITER 22. BEN BERMAN DIRECTOR 23. TIM KIRKBY DIRECTOR 23. HARTLEY GORENSTEIN 12 LINE PRODUCER A SWEET AND SURREAL LOOK AT THE (Unforgettable) as “Liz,” Josh’s intimidating older life-and-death stakes of dating, Man Seeking sister; and Maya Erskine (Betas) as “Maggie,” Woman follows naïve twenty-something “Josh the ex-girlfriend Josh can never quite forget. Greenberg” (Jay Baruchel, How to Train Your Man Seeking Woman is based on Simon Rich’s Dragon) on his unrelenting quest for love. Josh book of short stories, The Last Girlfriend on soldiers through one-night stands, painful break- Earth. Rich created the 10-episode scripted ups, a blind date with a troll, time travel, sex comedy and also serves as Executive Producer/ aliens, many deaths and a Japanese penis Showrunner. Jonathan Krisel, Andrew Singer monster named “Tanaka” on his fantastical and Lorne Michaels, and Broadway Video also journey to find love. serve as Executive Producers. Man Seeking Starring alongside Baruchel are Eric Andre Woman is produced by FX Productions. -

Profile2019 Well-Eas

® FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR JOSH HECHT Hard to believe our 18-month season explor- "Profile Theatre’s ing the work of Lisa Kron and Anna Deavere Smith is coming to a close! Profile Theatre’s unique mission unique mission allows us to dive deep into a master artist’s evolving vision of our allows us to shared world. We started the season with 2.5 Minute Ride, dive deep into Lisa’s alternately hysterical and poignant solo show that weaves together the mortifica- a master artist’s tions of bringing her girlfriend on her family’s annual summer vacation to the Cedar Point evolving vision Amusement Park with her soul-expanding trip accompanying her father to Auschwitz, of our where his parents were killed and where she comes to understand better the joys and sorrows of her father’s heart. shared world." We followed that with a concert staging of Twilight, Anna Deavere Smith’s documentary piece about the Rodney King unrest in Los Angeles, in 1992 and the complex layers of communities in conflict and police brutality that have remained disturbingly current in our society. Next, we presented The Secretaries, an outrageous and bawdy comedy about sexual politics and internalized misogyny in the workplace from The Five Lesbian Brothers, a writing collective and performance troupe Lisa Kron co-founded. In the fall, we presented Fires In The Mirror, Anna Deavere Smith’s ground- breaking work chronicling the race riots that erupted in Crown Heights, Brooklyn when a rabbi’s motorcade struck and killed a West Indian-American boy and a Jewish rabbinical student was slain in retaliation. -

Click Here to Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined 4 x 2” ad Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! October 8 - 14, 2020 has a new home at THE LINKS! Other stars 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 make music for Jacksonville Beach ‘GRAMMY Salute’ Offering: · Hydrafacials on PBS special · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring Jimmy Jam hosts “Great · B12 Complex / Performances: GRAMMY Lipolean Injections Salute to Music Legends” INSIDE: Sports listings, Friday on PBS. sports quiz and Get Skinny with it! player profile (904) 999-09771 x 5” ad Pages 18-19 www.SkinnyJax.com Now is a great time to It will provide your home: List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while the home is listed • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a Broker Associate home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with [email protected] ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan America’s Preferred Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! Home Warranty for your home when we put it on the market. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN A new ‘GRAMMY Salute to Music Legends’ honors John What’s Available NOW On Prine, Chicago and others Each year, several music icons get a special their horn parts. -

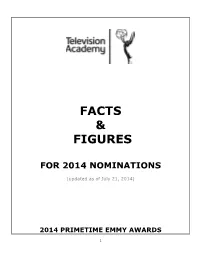

95 Updated Facts/Trivia Copy

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2014 NOMINATIONS (updated as of July 21, 2014) 2014 PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS 1 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2013 Behind The Candelabra – 11 Boardwalk Empire – 5 66th Annual Tony Awards – 4 Saturday Night Live – 4 The Big Bang Theory - 3 Breaking Bad – 3 Disney Mickey Mouse Croissant de Triomphe – 3 House of Cards -3 Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence In The House of God - 3 30 Rock - 2 The 55th Annual Grammy Awards – 2 American Horror Story: Asylum- 2 American Masters – 2 Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown – 2 The Colbert Report – 2 Da Vinci’s Demons – 2 Deadliest Catch – 2 Game of Thrones - 2 Homeland – 2 How I Met Your Mother - 2 The Kennedy Center Honors - 2 The Men Who Built America - 2 Modern Family – 2 Nurse Jackie – 2 Veep – 2 The Voice - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2013 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Modern Family Drama Series: Breaking Bad Miniseries or Movie: Behind The Candelabra Reality-Competition Program: The Voice Variety, Music or Comedy Series: The Colbert Report PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Julia Louis-Dreyfus (Veep) Lead Actor: Jim Parsons (The Big Bang Theory) Supporting Actress: Merritt Wever (Nurse Jackie) Supporting Actor: Tony Hale (Veep) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Claire Danes (Homeland) Lead Actor: Jeff Daniels (The Newsroom) Supporting Actress: Anna Gunn (Breaking Bad) Supporting Actor: Bobby Cannavale (Boardwalk Empire) Miniseries/Movie: Lead Actress: Laura Linney (The Big C: Hereafter) Lead Actor: Michael Douglas (Behind The Candelabra) Supporting Actress: Ellen Burstyn (Political Animals) Supporting