Geometric Average Capitalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Paper on the Market Structure for Thinly Traded Securities

Division of Trading and Markets: Background Paper on the Market Structure for Thinly Traded Securities I. Introduction The staff in the Division of Trading and Markets of the Securities and Exchange Commission is issuing this background paper1 in relation to the Commission Statement on Market Structure Innovation for Thinly Traded Securities to provide information regarding the trading challenges and characteristics of those national market system (“NMS”) stocks that trade in lower volume (“thinly traded securities”).2 We summarize a variety of materials regarding secondary market trading of thinly traded securities, including a 2018 market analysis by the Division of Trading and Markets’ Office of Analytics and Research (“OAR”) and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s 2017 report on the regulation of the U.S. capital markets (“Capital Markets Report”).3 In addition, we discuss the Commission staff Roundtable on Market Structure for Thinly-Traded Securities (“Roundtable”),4 where the dialogue among market participants and the comments submitted centered on the unique trading characteristics of thinly traded securities. Finally, we discuss the current regulatory framework for thinly traded securities. II. Trading Characteristics of Secondary Market Trading for Thinly Traded Securities A. SEC Staff Study The data in a recent study prepared by OAR5 indicated that approximately one-half of all NMS stocks have an average daily trading volume (“ADV”) of less than 100,000 shares and constitute less than two percent of all daily share volume. 1 This background paper represents the views of staff of the Division of Trading and Markets. It is not a rule, regulation, or statement of the Commission. -

Market Cap: In-Depth Guide of Stock Market Capitalization Analysis

Market Cap: In-Depth Guide of Stock Market Capitalization Analysis What Does Market Cap Mean? “Market capitalization refers to the total dollar market value of a company’s outstanding shares. Commonly referred to as ‘market cap,’ it is calculated by multiplying a company’s shares outstanding by the current market price of one share. The investment community uses this figure to determine a company’s size, as opposed to using sales or total asset figures.” What is a Stock’s Market Value? An important aspect of determining a stock’s worth is looking at its market value. The market value is the price that an asset would command. Figuring out the general market value of stocks and some other financial instruments like futures is pretty simple, since the market rates are extremely easy to find. A company’s true market value requires more than just the market cap. For the most accurate snapshot, you need to consider things like the P/E Ratio (Price to Earnings Ratio), the return on equity, and the EPS (Earnings Per Share) of the company in question. Market Cap vs. Market Value Both market cap and market value can be used to review the value of a company. They sound similar, and sometimes people use the terms interchangeably. The market cap is a metric that is based on the stock price. To determine a company’s market cap, all you have to do is multiply the current share price by the number of shares outstanding. With that in mind, it’s kind of understandable why the term market value is used interchangeably with market cap. -

The Role of Stockbrokers

The Role of Stockbrokers • Stockbrokers • Act as intermediaries between buyers and sellers of securities • Typically paid by commissions • Must be licensed by SEC and securities exchanges where they place orders • Client places order, stockbroker sends order to brokerage firms, who executes order on the exchanges where firm owns seats Types of Brokerage Firms • Full-Service Broker • Offers broad range of services and products • Provides research and investment advice • Examples: Merrill Lynch, A.G. Edwards • Premium Discount Broker • Low commissions • Limited research or investment advice • Examples: Charles Schwab Types of Brokerage Firms (cont’d) • Basic Discount Brokers • Main focus is executing trades electronically online • No research or investment advice • Commissions are at deep-discount Selecting a Stockbroker • Find someone who understands your investment goals • Consider the investing style and goals of your stockbroker • Be prepared to pay higher fees for advice and help from full-service brokers • Ask for referrals from friends or business associates • Beware of churning: increasing commissions by causing excessive trading of clients’ accounts Table 3.5 Major Full-Service, Premium Discount, and Basic Discount Brokers Types of Brokerage Accounts • Custodial Account: brokerage account for a minor that requires parent or guardian to handle transactions • Cash Account: brokerage account that can only make cash transactions • Margin Account: brokerage account in which the brokerage firms extends borrowing privileges • Wrap Account: -

Frequently Asked Questions About Initial Public Offerings

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT INITIAL PUBLIC OFFERINGS Initial public offerings (“IPOs”) are complex, time-consuming and implicate many different areas of the law and market practices. The following FAQs address important issues but are not likely to answer all of your questions. • Public companies have greater visibility. The media understanding IPOS has greater economic incentive to cover a public company than a private company because of the number of investors seeking information about their What is an IPO? investment. An “IPO” is the initial public offering by a company • Going public allows a company’s employees to of its securities, most often its common stock. In the share in its growth and success through stock united States, these offerings are generally registered options and other equity-based compensation under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the structures that benefit from a more liquid stock with “Securities Act”), and the shares are often but not an independently determined fair market value. A always listed on a national securities exchange such public company may also use its equity to attract as the new York Stock exchange (the “nYSe”), the and retain management and key personnel. nYSe American LLC or one of the nasdaq markets (“nasdaq” and, collectively, the “exchanges”). The What are disadvantages of going public? process of “going public” is complex and expensive. • The IPO process is expensive. The legal, accounting upon the completion of an IPO, a company becomes and printing costs are significant and these costs a “public company,” subject to all of the regulations will have to be paid regardless of whether an IPO is applicable to public companies, including those of successful. -

Capital Formation Market Trends: Ipos and Follow-On Offerings

Professional Perspective Capital Formation Market Trends: IPOs and Follow-On Offerings Anna Pinedo and Carlos Juarez, Mayer Brown LLP Reproduced with permission. Published February 2020. Copyright © 2020 The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. 800.372.1033. For further use, please visit: http://bna.com/copyright-permission-request/ Capital Formation Market Trends: IPOs and Follow-On Offerings Contributed by Anna Pinedo and Carlos Juarez, Mayer Brown LLP The capital formation environment has significantly changed in the last two decades and, in particular, following the global financial crisis of 2008. The number of initial public offerings has declined, and M&A exits have become a more attractive option for many promising companies. This article reviews trends in the initial public offering market, notable alternatives to IPOs, and follow-on offering activity. A Changing Environment While completing an IPO used to be seen as a principal objective of and signifier of success for entrepreneurs—and the venture capital and other institutional investors who financed emerging companies—this is no longer the case. Market structure and regulatory developments have changed capital-raising dynamics following the dot-com bust and financial crisis. At the same time, private capital alternatives also have become more varied and more significant. The number of IPOs drastically declined after 2000 compared to prior historic levels. After a brief increase in the number of IPOs following the aftermath of the dotcom bust, the number of IPOs declined again, partly as a result of the financial crisis. Changes in the regulation of research, enhanced corporate governance requirements, decimalization, a decline in the liquidity of small and mid-cap stocks, and other developments have been identified as contributing to the decline in the number of IPOs. -

New York Stock Exchange LLC; Notice of Filing

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION (Release No. 34-88441; File No. SR-NYSE-2020-21) March 20, 2020 Self-Regulatory Organizations; New York Stock Exchange LLC; Notice of Filing and Immediate Effectiveness of Proposed Rule Change to Suspend Until June 30, 2020 the Application of Its Continued Listing Requirement With Respect to Global Market Capitalization Pursuant to Section 19(b)(1) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Act”)1 and Rule 19b-4 thereunder,2 notice is hereby given that on March 19, 2020, New York Stock Exchange LLC (“NYSE” or the “Exchange”) filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) the proposed rule change as described in Items I and II below, which Items have been prepared by the Exchange. The Commission is publishing this notice to solicit comments on the proposed rule change from interested persons. I. Self-Regulatory Organization’s Statement of the Terms of Substance of the Proposed Rule Change The Exchange proposes to suspend until June 30, 2020 the application of its continued listing requirement that companies must maintain an average global market capitalization over a consecutive 30 trading-day period of at least $15 million (the “Market Capitalization Standard”). The proposed rule change is available on the Exchange’s website at www.nyse.com, at the principal office of the Exchange, and at the Commission’s Public Reference Room. II. Self-Regulatory Organization’s Statement of the Purpose of, and Statutory Basis for, the Proposed Rule Change In its filing with the Commission, the self-regulatory organization included statements concerning the purpose of, and basis for, the proposed rule change and discussed any comments it received on the proposed rule change. -

The Impact of Institutional Trading on Stock Prices

The impact of institutional trading on stock prices The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Lakonishok, Josef, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. 1992. “The Impact of Institutional Trading on Stock Prices.” Journal of Financial Economics 32 (1) (August): 23–43. doi:10.1016/0304-405x(92)90023- q. Published Version doi:10.1016/0304-405X(92)90023-Q Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:27692662 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA NBER WORKING PAPERS SERIES DO INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS DESTABILIZE STOCK PRICES? EVIDENCE ON HERDING ANDFEEDBACKTRADING Josef Lakonishok Andrei Shleifer Robert W. Vishny Working Paper No. 3846 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 September 1991 We are grateful to Louis Chan, Jay Ritter, Jeremy Stein, and Richard Thaler for helpful comments; and especially to Gil Beebower and Vasant Kamath for guidance with the data. Financial support from LOR-Nikko and Dimensional Fund Advisors is gratefully acknowledged. This paper is part of NBER's research program in Financial Markets and Monetary Economics. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #3846 September 1991 DO INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS DESTABILIZE STOCK PRICES? EVIDENCE ON HERDING AND FEEDBACK TRADING ABSTRACT This paper uses a new data set of quarterly portfolio holdings of 769 all-equity pension funds between 1985 and 1989 to evaluate the potential effect of their trading on stock prices. -

The Big Bang: Stock Market Capitalization in the Long Run ?

The Big Bang: Stock Market Capitalization in the Long Run ? Dmitry Kuvshinov and Kaspar Zimmermann † April 2019 Abstract This paper presents new annual long-run stock market capitalization data for 17 advan- ced economies. Going beyond benchmark year estimates of Rajan and Zingales( 2003) reveals a striking new time series pattern: over the long run, the evolution of stock market size resembles a hockey stick. The ratio of stock market capitalization to GDP was stable between 1870 and 1980, tripled with a “big bang” in the 1980s and 1990s, and remains high to this day. We use novel data on equity returns, prices and cashflows to explore the underlying drivers of this sudden structural shift. Our first key finding is that the big bang is driven almost entirely by rising equity prices, not quantities. Net equity issuance is sizeable but relatively constant over time, and plays very little role in the short and long run dynamics of market cap. Second, this price increase is explained by a mix of higher dividend payments, and a higher valuation – or a lower discount rate – of the underlying dividend stream. Third, high market capitalization forecasts low subsequent equity returns, outperforming standard predictors such as the price-dividend ratio. Our results imply that rather than measuring financial efficiency, stock market capitalization is best used as a “Buffet indicator” of investor risk appetite. Keywords: Stock market capitalization, financial development, financial wealth, equity valuations, risk premiums, return predictability JEL classification codes: E44,G10,N10,N20,O16 ?This work is part of a larger project kindly supported by a research grant from the Bundesministerium fur¨ Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). -

Rules of the Stock Market Gametm

Rules of The Stock Market GameTM Portfolio Rules 1. Each team begins the simulation with $100,000 in cash and may borrow additional funds. How much you may borrow is dependent on the equity in your account. Teams that buy on margin must maintain the Minimum Maintenance requirement. If you dip below this level, you will receive a margin call and must sell off enough investments to meet Minimum Maintenance. If a team still has not met its Minimum Maintenance requirement within seven days, the SMG system will automatically liquidate enough of the portfolio’s investments to collect the required amount. 2. Interest is charged weekly on negative cash balances at an annual rate of 7%, and credited weekly on positive cash balances at an annual rate of 0.75%. Interest is calculated daily, then summed for the week (Saturday – Friday) and posted Saturday (with Friday's date). The daily rate is based on a 365-day year. Daily Interest = Cash x Appropriate Interest Rate (as a decimal) / 365. Bond coupon payments will be posted when due. Bond buyers will also be charged for accrued interest since the last coupon payment. Bond sellers will receive accrued interest since the last coupon payment. 3. Teams may trade only stocks and mutual funds listed on the NASDAQ Stock Market and the New York Stock Exchange. Teams cannot trade over-the-counter or “pink sheet” stocks since they often price incorrectly. In addition, extremely volatile stocks or stocks that trade infrequently are not permitted and may be liquidated to protect portfolio stability. SMG reserves the right to cancel transactions in these securities as deemed necessary. -

Flight-To-Liquidity and Global Equity Returns

Flight-to-Liquidity and Global Equity Returns Ruslan Goyenko and Sergei Sarkissian * First draft: November 2007 This draft: October 2008 * The authors are from the Faculty of Management, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A1G5, Canada. Goyenko maybe reached at [email protected] and Sarkissian maybe reached at [email protected]. We thank Yakov Amihud, Kristin Forbes, Andrew Karolyi, Michael Schill, Pedro Santa Clara, and Akiko Watanabe, as well as participants of the Seventh Darden International Finance Conference, the 2008 European Finance Association Meeting, the 2008 World Bank Conference on Risk Analysis and Management and the workshops at the ISCTE Business School and Durham University for useful comments. We are also grateful to Sam Henkel for providing international stock liquidity data. Goyenko acknowledges financial support from IFM2. Sarkissian acknowledges financial support from IFM2, SSHRC, and the Desmarais Faculty Scholarship. Flight-to-Liquidity and Global Equity Returns ABSTRACT Investment practice and academic literature document a great degree of interaction between stock markets around the world and most liquid and safest assets such as the US Treasury bonds. Using data from 46 markets, we examine the joint impact of the “flight-to-liquidity” and “flight-to- quality” on global asset valuation. Our proxy for the flight-to-liquidity/quality is the illiquidity of US short-term Treasury bonds. We find that it is a leading indicator of the stock market illiquidity, and that it is also a strong predictor of future equity returns in both developed and emerging markets. This predictive relation remains intact after controlling for other global and local variables, including the lagged US term spread, dividend yields, equity market returns, as well as global and local stock market illiquidity. -

Effect of Firms' Market Capitalization on Stock Market Volatility of Companies

EFFECT OF FIRMS’ MARKET CAPITALIZATION ON STOCK MARKET VOLATILITY OF COMPANIES LISTED AT THE NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE MUSEBE BELLARMINE VICTOR CHESSAR A Research Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Business Administration. UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI October 2015 i DEDICATION I dedicate this research paper to my loving family, all of whom have been a source of great inspiration and support. May God bless you abundantly. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost I would like to thank God for affording me the opportunity to enroll for the program and for seeing me through to this point. To my parents, Professor and Dr. Musebe, and siblings for the guidance and much needed assistance they offered throughout my life and also in the preparation and development of this paper I would like to acknowledge the University of Nairobi Masters of Business Administration program, particularly the insights acquired in the financial seminar course about academic writing and analysis of past studies conducted in the topic. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Duncan Elly Ochieng for the helpful and insightful input and comments which were quite important in conducting this research paper Finally, to all those who in one way or another, contributed towards my academic and social life as an MBA student, either directly or indirectly, I will forever remain grateful to you all. iii ABSTRACT The main objective of this research paper was to analyze the relation between market capitalization and stock market volatility in the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Market capitalization is an important measure for investors in the determination of the returns on their investment. -

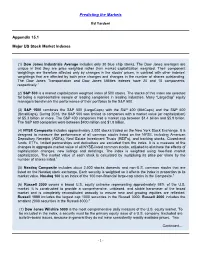

Appendix 15.1 Major US Stock Market Indexes

Predicting the Markets Ed Yardeni Appendix 15.1 Major US Stock Market Indexes (1) Dow Jones Industrials Average includes only 30 blue chip stocks. The Dow Jones averages are unique in that they are price weighted rather than market capitalization weighted. Their component weightings are therefore affected only by changes in the stocks’ prices, in contrast with other indexes’ weightings that are affected by both price changes and changes in the number of shares outstanding. The Dow Jones Transportation and Dow Jones Utilities indexes have 20 and 15 components, respectively.1 (2) S&P 500 is a market capitalization weighted index of 500 stocks. The stocks of this index are selected for being a representative sample of leading companies in leading industries. Many “LargeCap” equity managers benchmark the performance of their portfolios to the S&P 500. (3) S&P 1500 combines the S&P 500 (LargeCaps) with the S&P 400 (MidCaps) and the S&P 600 (SmallCaps). During 2016, the S&P 500 was limited to companies with a market value (or capitalization) of $5.3 billion or more. The S&P 400 companies had a market cap between $1.4 billion and $5.9 billion. The S&P 600 companies were between $400 million and $1.8 billion. (4) NYSE Composite includes approximately 2,000 stocks traded on the New York Stock Exchange. It is designed to measure the performance of all common stocks listed on the NYSE, including American Depository Receipts (ADRs), Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), and tracking stocks. Closed-end funds, ETFs, limited partnerships and derivatives are excluded from the index.