Repetition, Rewriting, and Contemporary Returns to Charles Dickens's Great Expectations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Expectations on Screen

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Tesis presentada por Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Licenciada en Periodismo y en Comunicación Audiovisual para la obtención del grado de Doctor Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities) “Now why should the cinema follow the forms of theater and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects?” (Sergei Eisenstein, “A dialectic approach to film form”) “An honest adaptation is a betrayal” (Carlo Rim) Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Early expressions: between hostility and passion 22 Towards a theory on film adaptation 24 Story and discourse: semiotics and structuralism 25 New perspectives 30 CHAPTER 3. -

Magwitch's Revenge on Society in Great Expectations

Magwitch’s Revenge on Society in Great Expectations Kyoko Yamamoto Introduction By the light of torches, we saw the black Hulk lying out a little way from the mud of the shore, like a wicked Noah’s ark. Cribbed and barred and moored by massive rusty chains, the prison-ship seemed in my young eyes to be ironed like the prisoners (Chapter 5, p.34). The sight of the Hulk is one of the most impressive scenes in Great Expectations. Magwitch, a convict, who was destined to meet Pip at the churchyard, was dragged back by a surgeon and solders to the hulk floating on the Thames. Pip and Joe kept a close watch on it. Magwitch spent some days in his hulk and then was sent to New South Wales as a convict sentenced to life transportation. He decided to work hard and make Pip a gentleman in return for the kindness offered to him by this little boy. He devoted himself to hard work at New South Wales, and eventually made a fortune. Magwitch’s life is full of enigma. We do not know much about how he went through the hardships in the hulk and at NSW. What were his difficulties to make money? And again, could it be possible that a convict transported for life to Australia might succeed in life and come back to his homeland? To make the matter more complicated, he, with his money, wants to make Pip a gentleman, a mere apprentice to a blacksmith, partly as a kind of revenge on society which has continuously looked down upon a wretched convict. -

Announcement

Announcement 10 articles, 2016-02-12 06:00 1 Accessory of the Day: New York Fashion Week, Fall 2016 For fall, Creatures of the Wind designers Shane Gabier and Christopher Peters collaborated with jeweler Pamela Love. 2016-02-12 05:41:52 923Bytes wwd.com 2 Primark to Open Six Stores in U. S. in 2016 The retailer is eyeing mainly suburban locations after opening on downtown Boston. 2016-02-12 05:31:52 2KB wwd.com 3 ecdm architectes completes new city hall for bezons ecdm architectes has completed the new city hall of bezons, a commune in the suburbs of northwestern paris. 2016-02-12 04:04:38 2KB www.designboom.com 4 “Agitprop!” at the Brooklyn Museum: Waves of Dissent, Legacies of Change The Brooklyn Museum's Agitprop! (through Aug. 7) explores the many ways that artists directly address issues of public concern. Opening last December, works will be added to Agitprop! twice in its nine-month run, once in February and again in April, to reflect how multiple generations of artists have tackled the same concerns over time. 2 10KB www.artinamericamagazine.com 5 Camille Henrot Entering French-born Camille Henrot's first solo show at Metro Pictures, I recalled a vivid early memory: my first time hearing an answering machine. I stood in the kitchen in the late '80s, clutching our outdated avocado-colored rotary phone, while my mother dialed my grandparents. Instead of answering my chipper greeting, the canned voice on the line recited the leave-a-message-at-the-beep spiel. It's not them! What's happening? I shrieked, my mother confused until she grabbed the receiver and laughed. -

Norms Governing the Dialect Translation of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations: an English-Greek Perspective

International Linguistics Research; Vol. 1, No. 1; 2018 ISSN 2576-2974 E-ISSN 2576-2982 https://doi.org/10.30560/ilr.v1n1p49 Norms Governing the Dialect Translation of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations: An English-Greek Perspective Despoina Panou1 1 Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting, Ionian University, Greece Correspondence: Despoina Panou, Department of Foreign Languages, Translation and Interpreting, Ionian University, Greece. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 11, 2018; Accepted: March 28, 2018; Published: April 16, 2018 Abstract This paper aims to investigate the norms governing the translation of fiction from English into Greek by critically examining two Greek translations of Charles Dickens’ novel Great Expectations. One is by Pavlina Pampoudi (Patakis, 2016) and the other, is by Thanasis Zavalos (Minoas, 2017). Particular attention is paid to dialect translation and special emphasis is placed on the language used by one of the novel’s prominent characters, namely, Abel Magwitch. In particular, twenty instances of Abel Magwitch’s dialect are chosen in an effort to provide an in-depth analysis of the dialect-translation strategies employed as well as possible reasons governing such choices. It is argued that both translators favour standardisation in their target texts, thus eliminating any language variants present in the source text. The conclusion argues that societal factors as well as the commissioning policies of publishing houses influence to a great extent the translators’ behaviour, and consequently, the dialect-translation strategies adopted. Hence, greater emphasis on the extra-linguistic, sociological context is necessary for a thorough consideration of the complexities of English-Greek dialect translation of fiction. -

Miss Havisham's Role Towards Estella's Personality As Seen in Great

MISS HAVISHAM’S ROLE TOWARDS ESTELLA’S PERSONALITY AS SEEN IN GREAT EXPECTATION BY CHARLES DICKENS Risma Kartika Dewi Email: [email protected] Program Studi Sastra Inggris, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Gresik Dwi Retno Novemi Maulidiyah Email: [email protected] PT. Wilmar Nabati Indonesia ABSTRACT This study is conducted to get better understanding regarding the role of family, particularly the role of mother towards personality of the child. In holding her role as an adopted mother for Estella, Miss Havisham adopts the type of parenting style in which she fully dominates and eleminates the rights of Estella. Miss Havisham has an intention to do the twisted revenge on men. She uses Estella as her media of taking revenge. She puts her ambition on Estella without considering Estella’s desire. Her own disappointment leading her to foster an adoptive daughter under her control. The writer interests to discuss more detail whether Miss Havisham’s parenting style can influence to the personality of Estella or not. In Writing the thesis, the writer uses literary approach which is linked with descriptive qualitative. After collecting the data, the writer classifies and clarifies the data which are related to the topic being discussed. The finding of this study shows that there is parent involvement process in forming Estella’s thought, identity and achievement. The writer concludes that Miss Havisham’s parenting style is not the best way in parent involvement process because it generates the negative impacts on Estella’s personality. Key words : Role, Parenting Style, and Motive I. INTRODUCTION who named Estella, since she has no desire to marry anymore, to console her seclusion life. -

Answer Sheet

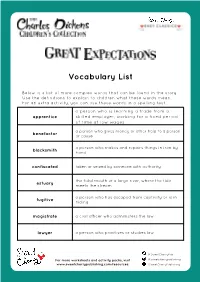

Vocabulary List Below is a list of more complex words that can be found in the story. Use the definitions to explain to children what these words mean. For an extra activity, you can use these words in a spelling test. a person who is learning a trade from a apprentice skilled employer, working for a fixed period of time at low wages a person who gives money or other help to a person benefactor or cause a person who makes and repairs things in iron by blacksmith hand confiscated taken or seized by someone with authority the tidal mouth of a large river, where the tide estuary meets the stream a person who has escaped from captivity or is in fugitive hiding magistrate a civil officer who administers the law lawyer a person who practises or studies law @SweetCherryPub For more worksheets and activity packs, visit @sweetcherrypublishing www.sweetcherrypublishing.com/resources. /SweetCherryPublishing Plot Sequencing Answer Sheet 1. Pip lives with his sister and her husband, Joe. One day, a big grey man approaches Pip when he visits his parents’ graves. The man asks Pip to bring him food and a file to cut off the cuffs on his ankles. 2. Pip agrees and later finds out that the man is an escaped convict from a nearby prison ship. The police find the man and Pip makes sure he knows that he never told on him. 3. Pip meets Miss Havisham and Estella at Sati’s House. Although Estella is cold towards him, he visits regularly for a few years before his apprenticeship starts and Estella leaves for London. -

The Purpose of Dialect in Charles Dickens's Novel Great Expectations

The Purpose of Dialect in Charles Dickens’s Novel Great Expectations Minna Pukari Bachelor’s seminar and thesis (682285A) English philology, Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Autumn, 2015 Abstract In this study, I was interested in finding out what purpose dialects serve in Charles Dickens’s novel Great Expectations. I used Susan Ferguson’s notions on ficto-linguistics and Peter Stockwell’s ideas on invented language to create the theoretical background for my study. The analysis focused on three characters of the novel, namely Joe Gargery, Abel Magwitch, and Pip. I examined what role dialect – in the case of Pip, the lack of one – plays in the character construction of these three characters. Additionally I analysed the dialects in relation to the major themes of the novel. The findings of this study suggest, that Dicken’s used dialect to both individualise characters and to bind them to a certain groups, which can mostly be defined by social status. The dialects also help make the themes of social mobility, gentility, social injustice, and expectations in relation to reality more tangible. 1 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 Literary dialect: Dickens as a dialect writer ........................................................................................... -

Gothic, Sensationalist and Melodramatic Reflections of Miss Havisham

(Re)Imagining the (Neo)Victorian Spinster: Gothic, Sensationalist and Melodramatic Reflections of Miss Havisham By Maria Dimitriadou A dissertation submitted to the Department of English Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki January 2014 (Re)Imagining the (Neo)Victorian Spinster: Gothic, Sensationalist and Melodramatic Reflections of Miss Havisham By Maria Dimitriadou APPROVED: 1. ________________________ 2. ________________________ 3. ________________________ Examining Committee ACCEPTED: _____________________ Department Chairperson Table of Contents Acknowledgements.....................................................................................................v Abstract.........................................................................................................................vi List of Figures............................................................................................................vii Introduction..................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Victorian Representations of the Spinster 1.1 Before Miss Havisham: The Gothic/Sensationalist Background of Great Expectations.......................................................................................................................9 1.2 Dickens and Gothic Fantasy: Imagining Miss Havisham in Great Expectations.....................................................................................................................20 -

The Analysis of Pip's Characteristics in Great Expectations

Sino-US English Teaching, June 2016, Vol. 13, No. 6, 499-504 doi:10.17265/1539-8072/2016.06.007 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Analysis of Pip’s Characteristics in Great Expectations LUO Jian-ting Sichuan University of Arts and Science, Dazhou, China Great Expectations can be said to have broken Dickens’ character which has always been the perfect. As a realistic writer, Charles Dickens is through the description of the ordinary people, reflecting the reality in his life time. No one is perfect, and everyone has its markers. Seeing from the novel the hero Pip, we still even have a lot to learn. Individual growth is a process of growing to be a perfect oneself. In order to achieve our goal in the future, whether big or small, success or failure, one should depend on himself/herself, relying on his or her own ability to realize the great expectations. Keywords: Great Expectations, Pip, characteristics Introduction Charles Dickens is said to be as central to the Victorian novel as Tennyson is to Victorian poetry. Great Expectations (1860–1861) is an important work in his late years and its story is not complicated. It tells how the poor country boy Philip Pirrip (shortened as Pip) grows up with false expectations to finally return to a rather cruel exposure of reality. Pip is an orphan, who lives in the lower class, and has been brought up by his sister. His sister is a rude woman, and is so easy to lose her temper that all the family members will be received by her bad languages. -

Literature Report on Great Expectations

LITERATURE REPORT ON GREAT EXPECTATIONS MAIN CHARACTERS Philip Pirrip, nicknamed Pip, is an orphan. Pip is destined to be trained as a blacksmith, a lowly but skilled and honest trade, but strives to rise above his class after meeting Estella Havisham. Joe Gargery is Pip's brother-in-law, and his first father figure. A Blacksmith who is the only person Pip can be honest with. Mrs. Joe Gargery, Pip's hot-tempered adult sister, who brings him up by hand after the death of their parents, but complains constantly of the burden Pip, is to her. She ends her life handicapped after an attack Miss Havisham, wealthy spinster who takes Pip on as a companion, and whom Pip suspects is his benefactor. Miss Havisham does not discourage this as it fits into her own spiteful plans. She later apologizes to him. He accepts her apology and she gets badly burned when her dress gets on fire from a spark from the fireplace. Pip saves her, but she later dies from her injuries. Estella Havisham is Miss Havisham's adopted daughter, whom Pip pursues romantically throughout the novel. Since her ability to love has been ruined by Miss Havisham, she is unable to return Pip's passion. She warns Pip of this repeatedly, but he is unwilling or unable to believe her. The Convict, an escapee from a prison ship, whom Pip treats kindly, and who turns out to be his benefactor, at which time his real name is revealed to be Abel Magwitch, but who is also known as Provis and Mr. -

DICKENS FINAL with ILLUS.Ppp

The Dickens Calendar 2012 The Dickens Calendar 2012 Celebrating the bicentenary of Dickens’s birth. £6.00 each or £10.00 for 2 (plus postage) Contact Jarndyce to order your copy: Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 7631 4220 35 _____________________________________________________________ Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers 46, Great Russell Street Telephone: 020 - 7631 4220 (opp. British Museum) Fax: 020 - 7631 1882 Bloomsbury, Email: [email protected] London WC1B 3PA V.A.T. No. GB 524 0890 57 _____________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE CXCV WINTER 2011-12 THE DICKENS CATALOGUE Catalogue: Joshua Clayton Production: Carol Murphy All items are London-published and in at least good condition, unless otherwise stated. Prices are nett. Items on this catalogue marked with a dagger (†) incur VAT (current rate 20%) A charge for postage and insurance will be added to the invoice total. We accept payment by VISA or MASTERCARD. If payment is made by US cheque, please add $25.00 towards the costs of conversion. Email address for this catalogue is [email protected]. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES CURRENTLY AVAILABLE, price £5.00 each include: Social Science Parts I & II: Politics & Philosophy and Economics & Social History. Women III: Women Writers J-Q; The Museum: Books for Presents; Books & Pamphlets of the 17th & 18th Centuries; 'Mischievous Literature': Bloods & Penny Dreadfuls; The Social History of London: including Poverty & Public Health; The Jarndyce Gazette: Newspapers, 1660 - 1954; Street Literature: I Broadsides, Slipsongs & Ballads; II Chapbooks & Tracts; George MacDonald. JARNDYCE CATALOGUES IN PREPARATION include: The Museum: Jarndyce Miscellany; The Library of a Dickensian; Women Writers R-Z; Street Literature: III Songsters, Lottery Puffs, Street Literature Works of Reference. -

Charles Dickens's Miss Havisham: Her Expectations and Our Responses

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 2(3)2395-2399, 2012 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2012, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Charles Dickens’s Miss Havisham: Her Expectations and Our Responses Sayed Mohammad Anoosheh Associate Professor, Yazd University ABSTRACT One of the most significant figures in Charles Dickens novel Great Expectations in terms of affective power is Miss Havisham. Dickens's contemporary readers probably understood either consciously or sub- consciously that Miss Havisham's ill-fated marriage and her consequent behaviour made a peculiar sort of sense in their world. Since stories like Miss Havisham's have been told and re-told from Dicken's time to ours in the continuing narrative of Western experience, this frustrated spinster may seem familiar even to present-day readers. Infact, we respond to codes that inform Great Expectations almost intuitively: the differenc is that our intuitions are informed by two centuries of additional development both cultural and literary. Her characterization provides a model of the power of repressive forces especially in their dual roles as agents of society at large acting on individual and as internalized matter directing one to govern the conduct of self and others. For the twenty first century reader, the richness of the novel may be enhanced by the analysis that pays attention to the cultural dynamics at work during Dickens's time with an emphasis on what more recent psycho-analytic, social and literary narrative offer us for understanding. KEYWORDS: Dickens, Miss Havisham, Great Expectations, cultural analysis, narcissism. INTRODUCTION "Great Expectations" is often linked in readers' minds with earlier Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby and David Copperfield, in all four novels trace the careers of young men through difficulties to a serene conclusion.