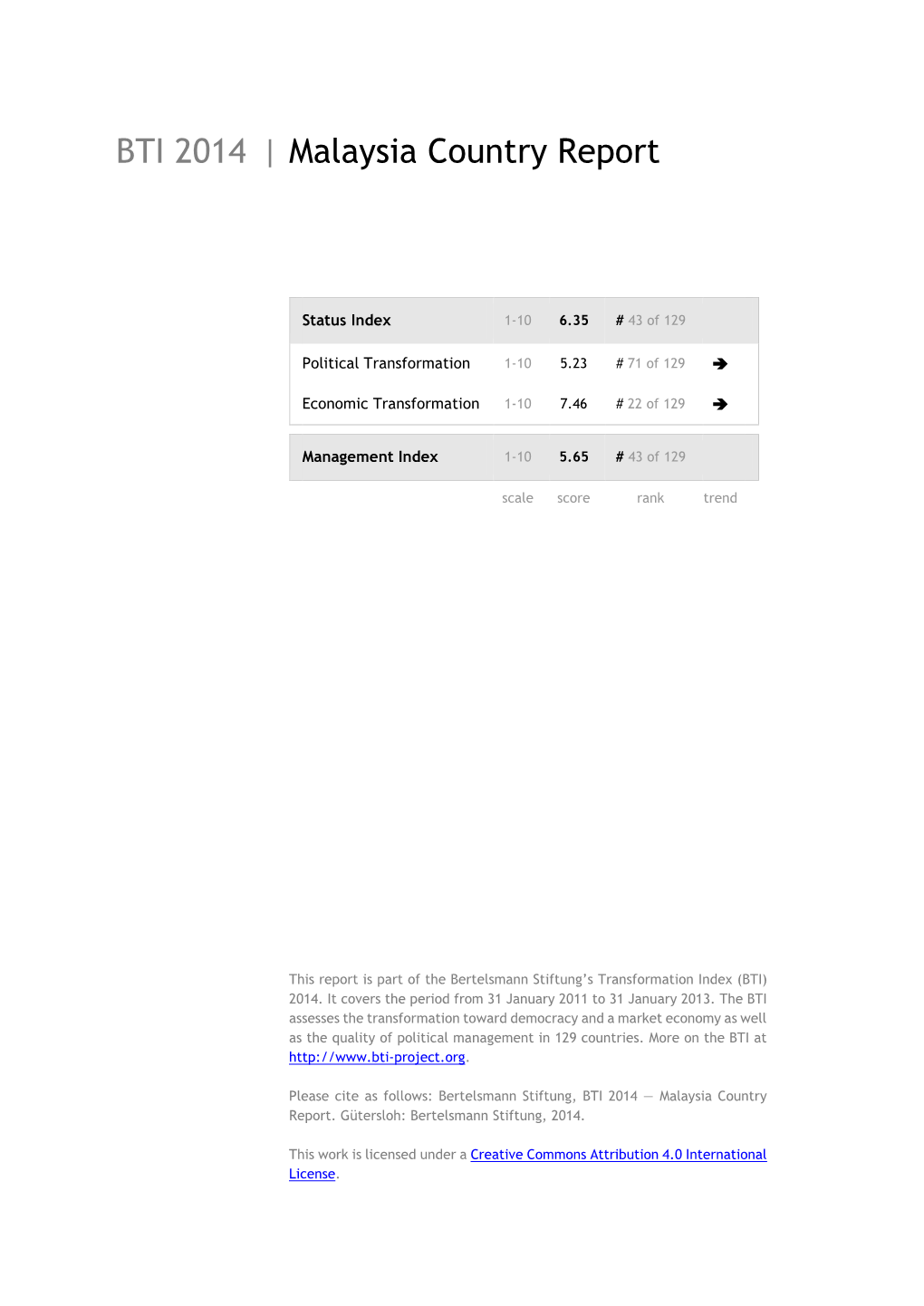

Malaysia Country Report BTI 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jenis Media Tajuk Berita Harian Azmin Jawab Hadi Berita Harian

Jenis Media Tajuk Berita Harian Azmin jawab Hadi Berita Harian Cacat penglihatan tetapi celik ilmu Berita Harian Polis nafi keluar kenyataan roboh kuil Batu Caves Berita Harian Masalah sampah di Kuala Langat membimbangkan Berita Harian Hampir 300 belia didedah peluang kerjaya Berita Harian Kebersihan Bandar Baru Bangi semakin merosot Berita Harian The Titans turun tempang Utusan Malaysia Hudud bukan dasar Pakatan Utusan Malaysia Tiada permohonan tukar status kedai kepada gereja Utusan Malaysia Arahan roboh kuil Batu Caves palsu -KPN Utusan Malaysia Kerjasama Serantau Utusan Malaysia Pengarah JPNIN Sabah terima Anugerah Khas JPM 2014 Utusan Malaysia Tindakan Utusan Malaysia Curi air: Syabas rugi RM4.7 juta Utusan Malaysia Syabas cadang badan bebas siasat paip pecah di Bukit Bintang Utusan Malaysia - Supplement Reka bentuk seksi, ikonik Harian Metro Terminal seksa Harian Metro Tak sangup tunggu setahun Harian Metro Periksa lebih kerap Harian Metro Kereta berjoget Harian Metro Buaian jahanam nanti mangsa Harian Metro Menembak bersama APMM Harian Metro Tong sampah anti monyet Harian Metro Pertandingan landskap tonjol Ampang Jaya Harian Metro PKR setia bersama 2 parti Harian Metro Melimpah masuk rumah Harian Metro Azmin tolak dakwaan Hadi Sinar Harian PKR tolak alasan hudud demi keselamatan Sinar Harian Gereja dibenarkan pasang semula salib Sinar Harian Dilanda banjir kilat kali ketiga Sinar Harian Beri tempoh hingga hujung tahun Sinar Harian Jais mahu semuka Ekhsan Bukharee Sinar Harian Promosi bayaran kompaun MBSA Sinar Harian Ahli keluarga -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

World Bank Document

Updated as of October 13, 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized October 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Updated as of October 13, 2017 Updated as of October 13, 2017 Primer on Malaysia’s Experience with National Development Planning Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... I 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Malaysia’s Planning System: A Brief History ..................................................................................... 2 3. How Planning Works in Malaysia ...................................................................................................... 5 Institutional Architecture .............................................................................................................. 8 Connecting National Visions and Plans ...................................................................................... 13 Inter-Ministerial Coordination .................................................................................................... 14 Stakeholder Consultation and Input ........................................................................................... 15 Planning and Budgeting ............................................................................................................... 16 -

<Notes> Malaysia's National Language Mass Media

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository <Notes> Malaysia's National Language Mass Media : History Title and Present Status Author(s) Lent, John A. Citation 東南アジア研究 (1978), 15(4): 598-612 Issue Date 1978-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/55900 Right Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University South East Asian Studies, Vol. 15, No.4, March 1978 Malaysia's National Language Mass Media: History and Present Status John A. LENT* Compared to its English annd Chinese language newspapers and periodicals, Nlalaysia's national language press is relatively young. The first recognized newspaper in the Malay (also called Bahasa Malaysia) language appeared in 1876, seven decades after the Go'vern ment Gazette was published in English, and 61 years later than the Chinese J!lonthly 1\1agazine. However, once developed, the Malay press became extremely important in the peninsula, especially in its efforts to unify the Malays in a spirit of national consciousness. Between 1876 and 1941, at least 162 Malay language newspapers, magazines and journals were published, plus eight others in English designed by or for Malays and three in Malay and English.I) At least another 27 were published since 1941, bringing the total to 200. 2) Of the 173 pre-World War II periodicals, 104 were established in the Straits Settlements of Singapore and Penang (68 and 36, respectively): this is understandable in that these cities had large concentrations of Malay population. In fact, during the first four decades of Malay journalism, only four of the 26 newspapers or periodicals were published in the peninsular states, all four in Perak. -

Conference Papers, Edited by Ramesh C

Quantity Meets Quality: Towards a digital library. By Jasper Faase & Claus Gravenhorst (Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Netherland) Jasper Faase Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Netherland Jasper Faase is a historian and Project Manager Digitization at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library of the Netherlands). Since 1999 Jasper has been involved in large scale digitization projects concerning historical data. In 2008 he joined the KB as coordinator of ‘Heritage of the Second World War’, a digitization programme that generated the following national collections: war diaries, propaganda material and illegally printed literature. He currently heads the Databank Digital Daily Newspapers project at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, as well as several other mass-digitization projects within the KB’s digitization department. Claus Gravenhorst CCS Content Conversion Specialists GmbH Claus Gravenhorst joined CCS Content Conversion Specialists GmbH in 1983, holds a diploma in Electrical Engineering (TU Braunschweig, 1983). Today he is the Director of Strategic Initiatives at CCS leading business development. For 10 years Claus was in charge of the product management of CCS products. During the METAe Project, sponsored by the European Union Framework 5, from 2000 to 2003 Claus collaborated with 16 international partners (Universities, Libraries and Research Institutions) to develop a conversion engine for books and journals. Claus was responsible for the project management, exploration and dissemination. The METAe Project was successfully completed in August 2003. Since 2003 he is engaged in Business Development and promoted docWORKS as a speaker on various international conferences and exhibitions. In 2006 Claus contributed as a co-author to “Digitalization - International Projects in Libraries and Archives”, published in June 2007 by BibSpider, Berlin. -

ANFREL E-BULLETIN ANFREL E-Bulletin Is ANFREL’S Quarterly Publication Issued As Part of the Asian Republic of Electoral Resource Center (AERC) Program

Volume 2 No.1 January – March 2015 E-BULLETIN The Dili Indicators are a practical distilla- voting related information to enable better 2015 Asian Electoral tion of the Bangkok Declaration for Free informed choices by voters. Stakeholder Forum and Fair Elections, the set of principles endorsed at the 2012 meeting of the Participants were also honored to hear Draws Much Needed AES Forum. The Indicators provide a from some of the most distinguished practical starting point to assess the and influential leaders of Timor-Leste’s Attention to Electoral quality and integrity of elections across young democracy. The President of the region. Timor-Leste, José Maria Vasconcelos Challenges in Asia A.K.A “Taur Matan Ruak”, opened the More than 120 representatives from twen- Forum, while Nobel Laureate Dr. Jose The 2nd Asian Electoral Stakeholder ty-seven countries came together to share Ramos-Jorta, Founder of the State Dr. ANFREL ACTIVITIES ANFREL Forum came to a successful close on their expertise and focus attention on the Marí Bim Hamude Alkatiri, and the coun- March 19 after two days of substantive most persistent challenges to elections in try’s 1st president after independence discussions and information sharing the region. Participants were primarily and Founder of the State Kay Rala 1 among representatives of Election from Asia, but there were also participants Xanana Gusmão also addressed the Management Bodies and Civil Society from many of the countries of the Commu- attendees. Each shared the wisdom Organizations (CSOs). nity of Portuguese Speaking Countries gained from their years of trying to (CPLP). The AES Forum offered represen- consolidate Timorese electoral democ- Coming two years after the inaugural tatives from Electoral Management Bodies racy. -

Anwar Ibrahim

- 8 - CL/198/12(b)-R.1 Lusaka, 23 March 2016 Malaysia MAL/15 - Anwar Ibrahim Decision adopted by consensus by the IPU Governing Council at its 198 th session (Lusaka, 23 March 2016) 2 The Governing Council of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Referring to the case of Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim, a member of the Parliament of Malaysia, and to the decision adopted by the Governing Council at its 197 th session (October 2015), Taking into account the information provided by the leader of the Malaysian delegation to the 134 th IPU Assembly (March 2016) and the information regularly provided by the complainants, Recalling the following information on file: - Mr. Anwar Ibrahim, Finance Minister from 1991 to 1998 and Deputy Prime Minister from December 1993 to September 1998, was dismissed from both posts in September 1998 and arrested on charges of abuse of power and sodomy. He was found guilty on both counts and sentenced, in 1999 and 2000 respectively, to a total of 15 years in prison. On 2 September 2004, the Federal Court quashed the conviction in the sodomy case and ordered Mr. Anwar Ibrahim’s release, as he had already served his sentence in the abuse of power case. The IPU had arrived at the conclusion that the motives for Mr. Anwar Ibrahim’s prosecution were not legal in nature and that the case had been built on a presumption of guilt; - Mr. Anwar Ibrahim was re-elected in August 2008 and May 2013 and became the de facto leader of the opposition Pakatan Rakyat (The People’s Alliance); - On 28 June 2008, Mohammed Saiful Bukhari Azlan, a former male aide in Mr. -

Lesser Government in Business: an Unfulfilled Promise? by Wan Saiful Wan Jan Policy Brief NO

Brief IDEAS No.2 April 2016 Lesser Government in Business: An Unfulfilled Promise? By Wan Saiful Wan Jan Policy Brief NO. 2 Executive Summary Introduction This paper briefly outlines the promise made by Reducing the Government’s role in business has the Malaysian Government to reduce its role in been on Prime Minister Dato’ Sri Najib Tun business as stated in the Economic Transformation Razak’s agenda since March 2010, when he Programme (ETP). It presents a general argument launched the New Economic Model (NEM). The of why the Government should not be involved NEM called for a reduction in Government in business. It then examines the progress intervention in the economy and an increase made by the Government to reduce its role in economic liberalisation efforts. The NEM in business through data showing Government furthermore, acknowledged that private sector divestments in several listed companies. growth in Malaysia has been hampered by “heavy Government and GLC presence” and This paper then demonstrates how this progress is offset by two factors – (i) the increased shares of Government-Linked Companies that there is a serious need to “reduce direct (GLCs) in the Kuala Lumpur Composite Index (KLCI) and (ii) the state participation in the economy” (National higher amount of combined GLC and GLIC asset acquisitions as opposed to asset disposals. This paper concludes with the argument Economic Advisory Council (NEAC), 2009). that the Government has not fulfilled its promise but in fact, has done the exact opposite. The increased shares of Government- 01 Linked Companies (GLCs) in the Kuala Author Two Factors Lumpur Composite Index (KLCI). -

5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 For

Aliran Monthly : Vol.31(3) Page 1 For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2011(026665) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2011:Vol.31No.3 COVER STORY Making sense of the forthcoming Sarawak state elections Will electoral dynamics in the polls sway to the advantage of the opposition or the BN? by Faisal S. Hazis n the run-up to the 10th all 15 Chinese-majority seats, spirit of their supporters. As III Sarawak state elections, which are being touted to swing contending parties in the com- II many political analysts to the opposition. Pakatan Rakyat ing elections, both sides will not have predicted that the (PR) leaders, on the other hand, want to enter the fray with the ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) will believe that they can topple the BN mentality of a loser. So this secure a two-third majority win government by winning more brings us to the prediction made (47 seats). It is likely that the coa- than 40 seats despite the opposi- by political analysts who are ei- lition is set to lose more seats com- tion parties’ overlapping seat ther trained political scientists pared to 2006. The BN and claims. Which one will be the or self-proclaimed political ob- Pakatan Rakyat (PR) leaders, on likely outcome of the forthcoming servers. Observations made by the other hand, have given two Sarawak elections? these analysts seem to represent contrasting forecasts which of the general sentiment on the course depict their respective po- Psy-war versus facts ground but they fail to take into litical bias. Sarawak United consideration the electoral dy- People’s Party (SUPP) president Obviously leaders from both po- namics of the impending elec- Dr George Chan believes that the litical divides have been engag- tions. -

Anti- Corruption Toolkit for Civic Activists

ANTI- CORRUPTION TOOLKIT FOR CIVIC ACTIVISTS Leveraging research, advocacy and the media to push for effective reform Anti-Corruption Toolkit for Civic Activists Lead Authors: Angel Sharma, Milica Djuric, Anna Downs and Abigail Bellows Contributing Writers: Prakhar Sharma, Dina Sadek, Elizabeth Donkervoort and Eguiar Lizundia Copyright © 2020 International Republican Institute. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the International Republican Institute. Requests for permission should include the following information: • The title of the document for which permission to copy material is desired. • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, e-mail address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: Attn: Department of External Affairs International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] This publication was made possible through the support provided by the National Endowment for Democracy. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Module 1: Research Methods and Security 2 Information and Evidence Gathering 4 Open Source 4 Government-Maintained Records 5 Interviews -

Countries at the Crossroads 2012: Malaysia

COUNTRIES AT THE CROSSROADS Countries at the Crossroads 2012: Malaysia Introduction Malaysia has over 28 million people, of whom approximately 63 percent are ethnic Malay, 25 percent Chinese, 7 percent Indian, and 4 percent Ibans and Kadazan-Dusun.1 Much of this diversity was created through the British formation of an extractive colonial economy, with the “indigenous” Malay community ordered into small holdings and rice cultivation, while the “non-Malays” were recruited from China and India into tin mining and plantation agriculture. Further, in preparing the territory for independence in 1957, the British fashioned a polity that was formally democratic, but would soon be encrusted by authoritarian controls. Throughout the 1960s, greater urbanization brought many Malays to the cities, where they encountered the comparative prosperity of the non-Malays. They perceived the multiethnic coalition that ruled the country, anchored by the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), but including the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), as doing little to enhance their living standards. At the same time, many non-Malays grew alienated by the discrimination they faced in accessing public sector resources. Thus, as voters in both communities swung to opposition parties in an election held in May 1969, the UMNO-led coalition, known as the Alliance, was gravely weakened. Shortly afterward, Malays and Chinese clashed in the capital, Kuala Lumpur, sparking ethnic rioting known as the May 13th incident. Two years of emergency rule followed during which parliament was closed. As the price for reopening parliament in 1971, UMNO imposed new curbs on civil liberties, thereby banning any questioning of the Malay “special rights” that are enshrined in constitution’s Article 153. -

Undocumented Migrants and Refugees in Malaysia: Raids, Detention and Discrimination

Undocumented migrants and refugees in Malaysia: Raids, Detention and Discrimination INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................................................4 CHAPTER I - THE MALAYSIAN CONTEXT................................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER II – THE DE FACTO STATUS OF REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS ..............................................................9 CHAPTER III – RELA, THE PEOPLE’S VOLUNTEER CORPS ...............................................................................................11 CHAPTER IV – JUDICIAL REMEDIES AND DEPRIVATION OF LIBERTY .............................................................................14 CHAPTER V – THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN......................................................................................................................15 CHAPTER VI – CONDITIONS OF DETENTION, PUNISHMENT AND SANCTIONS...............................................................18 RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................................................................................................................23 APPENDICE: LIST OF PERSONS MET BY THE MISSION .....................................................................................................29 March 2008 - N°489/2 Undocumented migrants and refugees in Malaysia: Raids, Detention and Discrimination