With Special Reference to Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

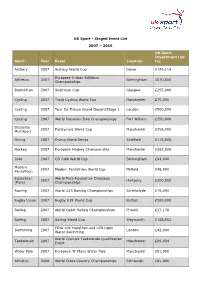

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

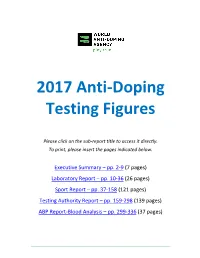

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

Scottish Disability Sport - the First Fifty Years Richard Brickley MBE Foreword

Scottish Disability Sport - The First Fifty Years Richard Brickley MBE Foreword I was delighted to be asked by Chief Executive Gavin Macleod to record the first fifty years of Scottish Disability Sport, to mark the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the Association. Initially the project was intended to be small but the more I researched, the more it brought back memories of great athletes, superb volunteers and great times. I became determined to try and do justice to as many as those great people as possible. I am certain I shall have forgotten key people in the eyes of others and if so I apologise profusely. For almost four decades SDS has been for me a way of life. The volunteers I have had the pleasure of working with for almost three decades are those I remember with great fondness, particularly during the early years. I applaud the many athletes who contributed to the rich history and success of SDS over fifty years. Outstanding volunteers like Bob Mitchell, Mary Urquhart, David Thomson, Jean Stone, Chris Cohen and Colin Rains helped to develop and sustain my passion for disability sport. I have been privileged to work with exceptional professionals like Ken Hutchison, Derek Casey, Liz Dendy, Paul Bush, Bob Price, Louise Martin, Sheila Dobie, Fiona Reid, Eddie McConnell, Gavin MacLeod, Mary Alison, Heather Lowden, Lawrie Randak, Tracey McCillen, Archie Cameron and many others whose commitment to inclusive sport has been obvious and long lasting. I thank Jean Stone, Jacqueline Lynn, Heather Lowden, Maureen Brickley and Paul Noble who acted as “readers” during the writing of the history and Norma Buchanan for administrative support at important stages. -

Management Meeting

` Minutes of the Ninety-fourth Meeting of the Management Committee of Scottish Disability Sport held on Monday 27 October 2008 at sportscotland, Caledonia House, South Gyle, Edinburgh EH12 9DQ at 16.00 hrs. Attendees: Gordon McCormack Chairman Jim Thomson Vice Chair Lauren MacTaggart Director Eileen Ramsay Director Frank Duffy Director Dave Rhoney Director Andrinne Craig Director Lyn Glen Director Gavin Macleod Chief Executive Officer Claire Mands National Development Officer Ruari Davidson Performance Development Officer Andy Bruce sportscotland Gill Penfold sportscotland, Partnership Manager Ailien Pallot Finance Manager Cynthia Clare Minutes Secretary Apologies: Charlie Forbes Director Millar Stoddart Director Jed Renilson Director Anna Tizzard Director The meeting opened with a presentation by Stuart Sharp, National Development Manager, Disability football, Scottish Football Association. Gordon McCormack welcomed everyone to the first meeting for the 2008/2009 session. ACTION 3.0 Minutes of the Meeting held on Monday 1 September 2008 Those present accepted the Minutes of the meeting held on Monday 1 September as an accurate account of the proceedings. 4.0 Matters Arising from Minutes of 11 February 2007 Minutes/Management Board Minutes October 2008 1 ACTION 7.6.1 Jed Renilson has spoken to Julian Butterfield, National Ongoing Grid, who will make contact with Scottish Disability Sport next time he is in the area. Matters Arising from Minutes of 19 May 2008 9.0.3 Mobile Phones for SDS officers. Further work is to be CEO carried out on possible options. Matters Arising from the Minutes of Monday 23 June 6.1 Sportscotland had done some research on the impact of disclosures on volunteers in sport. -

UK Sport - Staged Event List

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Passionate Talk Interview with Athletes for Paralympic Sports! ~Videoreleased on Official Website~

December 16, 2020 Less Than 300 Days Until the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Passionate Talk Interview with Athletes for Paralympic sports! ~VideoReleased on Official Website~ TOBU TOWER SKYTREE CO., LTD. TOBU TOWER SKYTREE CO., LTD., an Official Supporter of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games, believes in a “VIEW of HOPE.” We who operates the world’s tallest freestanding broadcasting tower -TOKYO SKYTREE- send support to all the athletes that aims to become the world’s best and their wishes and passion with keeping the momentum and the positive energy of Tokyo 2020 going. Athletes for Paralympic sports (Football 5-a-side athlete Kento Kato, Para Canoe athlete Monika Seryu, Para Taekwondo athlete Mitsuya Tanaka) were interviewed, and they discussed how they are going to spend their 300 days until the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic games, their hopes about this Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games, and about the“W1SH RIBBON” monument located on the TEMBO DECK of TOKYO SKYTREE. The interview footage can be accessed on the official website under the「Tokyo 2020 Special Page」tab. For further details please view the reference page. △Football 5-a-side Athlete Kento Kato △ Para Canoe Athlete Monika Seryu △Para Taekwondo Athlete Mitsuya Tanaka ©TOKYO-SKYTREE <Reference Page> Interview Footage of the Athletes for Paralympic sports Interviews were held with Kento Kato, Football 5-a-side athlete, Monika Seryu, Para Canoe athlete, and Mitsuya Tanaka, Para Taekwondo athlete. They were asked about what they feel“now” as there are less than 300 days until the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games. The interviews can be accessed via the links down below. -

View Our Progress Against the Last Strategic Plan for 2016 to 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 VERSION CONTROL 11/6/2020 Page 10: Dashboard updated Page 38: “NPLW Reserve grade won the Grand Final” amended to “lost” 2 CONTENTS Board of Directors ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Chair’s Report .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CEO’s Report .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Strategic Report ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Participation ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................12 Canberra United .........................................................................................................................................................................................................14 FFA Cup ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................16 -

Guía De Clasificación Para Deportes Paralímpicos

Universitat Miguel Hernández d’Elx Curs acadèmic: 2015- 2016 Grau en Ciències de l’Activitat Física i l’Esport Guia de classificació per a esports paralímpics Proposta d’intervenció Alumna: Núria Vilanova Périz Tutor acadèmic: Raúl Reina Vaíllo Centre en el que s’ha plantejat la proposta: Comité Paralímpic Espanyol Núria Vilanova Périz Grau en Ciències de l’Activitat Física i l’Esport. Índex 1. Contextualització. ......................................................................................................... 2 1.1. La classificació en esport adaptat. ....................................................................... 4 1.2. Objectius del Treball Final de Grau. ..................................................................... 5 2. Revisió bibliogràfica. ..................................................................................................... 5 3. Intervenció. .................................................................................................................. 5 4. Conclusions. ................................................................................................................. 9 5. Bibliografia. ................................................................................................................ 10 6. Annexos...................................................................................................................... 11 Annex 1 ....................................................................................................................... 11 1 | Pàg i n a Núria -

The Educator-Cover

The Educator VOLUME XVIII, ISSUE 1 JULY 2005 See pages 27-32 for important information on ICEVI’s 12th World Conference Sports and Recreation for Persons with Visual Impairment Playing the game of your life A Publication of ICEVI The International Council for Education of People with Visual Impairment ICEVI: PREPARING TO THE LAUNCH THE EFA CAMPAIGN Ever since ICEVI developed its strategic plan in 2002, one of its main objectives was to launch a global campaign to facilitate education for all children with visual impairment by 2015. A draft paper was discussed at the executive committee meeting of ICEVI held in Kuala Lumpur in 2004 and it was refined on the basis of the suggestions of the members. In the process, the paper also accommodated ideas of the joint educational policy statement of the ICEVI and World Blind Union and also the joint educational policy of the CBM and Sight Savers. ICEVI took the lead to prepare the draft INGO strategy paper on education to increase the services to children with visual impairment at the country levels. Leading organisations such as the World Blind Union, CBM, Sight Savers International, Norwegian Assoiciation for the Blind and Partially Sighted, Overbrook School for the Blind, Perkins School for the Blind, Foundation Dark and Light Blindcare, etc., along with ICEVI will be meeting in Madrid in late 2005 to chalk out detailed plans of action to take this EFA campaign to the grassroot levels. The summary of the draft paper circulated to the international umbrella organisations and also to the Non-Governmental Development Organisations is presented here for the benefit of the readers of The Educator. -

2018 WADA Monitoring Statistics Summary TOTAL Final.Xlsx

2018 WADA MONITORING PROGRAM In Competition Monitoring: Tramadol, Codeine, Hydrocodone In and Out of Competition Monitoring: Beta‐2 Agonists (multiple), Bemitil and Glucocorticoids Article 4.5 of the World Anti‐Doping Code 2015: "WADA, in consultation with Signatories and governments, shall establish a monitoring program regarding substances which are not on the Prohibited List, but which WADA wishes to monitor in order to detect patterns of misuse in sport." 2018 1 Olympic Sport** Tramadol* Codeine* Hydrocodone*Beta‐2 Agonists* Bemitil* (2‐ethylsulfanyl‐1H‐benzimidazole) Glucocorticoids* IC Samples >50 ng/mL IC Samples >50 ng/mL IC Samples >50 ng/mL IC Samples multiple OOC Samples multiple IC Samples >20 ng/mL OOC Samples >20 ng/mL IC Samples >1 ng/mL OOC Samples >1 ng/mL Aquatics 6150 9 6150 12 6150 ‐ 2802 31 3587 20 1576 1 1896 ‐ 2128 40 1871 32 Archery 658 7 658 ‐ 658 ‐ 291 ‐ 186 ‐ 167 ‐ 96 ‐ 228 ‐ 111 ‐ Athletics 15967 59 15967 28 15967 3 8037 5 5969 1 3108 1 4088 ‐ 4607 71 2874 36 Badminton 945 2 945 ‐ 945 ‐ 611 ‐ 523 ‐ 301 ‐ 276 ‐ 307 1 344 1 Basketball 3245 16 3245 5 3245 1 1215 ‐ 1040 ‐ 962 ‐ 445 ‐ 742 9 663 7 Boxing 2298 9 2298 ‐ 2298 ‐ 1056 ‐ 973 ‐ 483 ‐ 529 ‐ 631 12 499 4 Canoe/Kayak 1753 3 1753 4 1753 2 624 2 1081 ‐ 365 1 758 ‐ 466 4 663 10 Cycling 13381 574 13381 72 13381 1 6261 58 4556 30 2840 1 4383 ‐ 3819 194 1714 38 Equestrian 407 1 407 2 407 ‐ 87 ‐ 149 ‐ 178 ‐ 99 ‐ 47 1 113 1 Fencing 794 1 794 ‐ 794 ‐ 319 ‐ 436 ‐ 213 ‐ 278 ‐ 298 8 274 2 Field Hockey 754 1 754 5 754 1 262 ‐ 509 ‐ 258 ‐ 277 ‐ 172 ‐ 292 ‐ Football 24931 -

Security Policy, Social Networks, and Rio De Janeiro's Favelas Jason Bartholomew Scott Ph.D. Candidate D

Pacified Inclusion: Security Policy, Social Networks, and Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas Jason Bartholomew Scott Ph.D. Candidate Department of Anthropology University of Colorado-Boulder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosphy Department of Anthropology 2018 i This thesis entitled Pacified Inclusion: Security Policy, Social Networks, and Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas written by Jason Scott has been approved for the Department of Anthropology at the University of Colorado-Boulder Donna Goldstein Kaifa Roland Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 13-0015 ii Scott, Jason Bartholomew (Ph.D., Anthropology) Pacified Inclusion: Security Policy, Social Networks, and Rio de Janeiro’s Favelas Thesis Directed by Professor Donna M. Goldstein Dissertation Abstract This dissertation addresses the connections between everyday violence and digital technology. I describe three years of ethnographic research concerning a community policing program called “pacificação ” (pacification) in a Brazilian favela (shanty town). Alongside supporting a permanent police force that destabilized a powerful drug faction, pacification policy endorsed a wide range of social projects and dramatically reshaped the relationship between the Brazilian State and its marginalized citizens. Among the social projects associated with pacification were a number of “inclusão digital” (digital inclusion) programs that combined technical literacy with critical political literacy in the hope of disrupting exclusionary conditions. During my observations of these programs, I found what I call a hidden politics of digital reproduction. -

Lima 2019 Parapan American Games Qualification Guide

Lima 2019 Parapan American Games Qualification Guide 17 September 2018 International Paralympic Committee Adenauerallee 212-214 Tel. +49 228 2097-200 www.paralympic.org 53113 Bonn, Germany Fax +49 228 2097-209 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Lima 2019 Parapan American Programme Overview .......................................................... 5 3. General IPC Regulations On Eligibility ................................................................................. 7 4. Bipartite Commission Invitations ........................................................................................ 8 5. Redistribution Of Vacant Qualification Slots ........................................................................ 9 6. Universality Wild Cards ....................................................................................................... 9 7. Key Dates......................................................................................................................... 10 8. Para Athletics .................................................................................................................. 12 9. Para Badminton ............................................................................................................... 26 10. Boccia ............................................................................................................................. 37 11. Para Cycling ....................................................................................................................