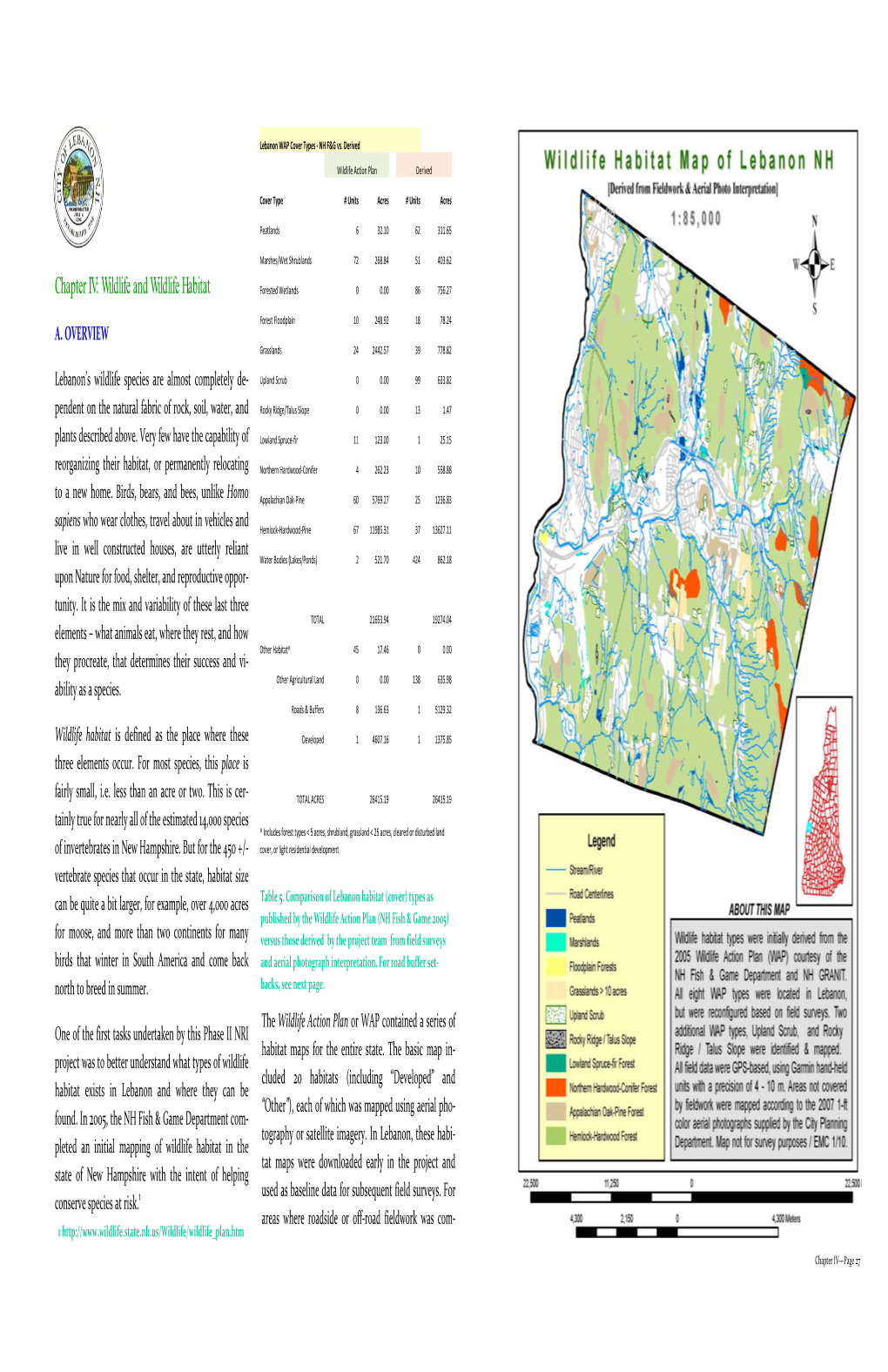

Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat Forested Wetlands 0 0.00 86 756.27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018

NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 ACWORTH COLD RIVER 111 ALBANY IONA LAKE 1 ALLENSTOWN ARCHERY POND 1 ALLENSTOWN BEAR BROOK 1 ALLENSTOWN CATAMOUNT POND 1 ALSTEAD COLD RIVER 1 ALSTEAD NEWELL POND 1 ALSTEAD WARREN LAKE 1 ALTON BEAVER BROOK 1 ALTON COFFIN BROOK 1 ALTON HURD BROOK 1 ALTON WATSON BROOK 1 ALTON WEST ALTON BROOK 1 AMHERST SOUHEGAN RIVER 11 ANDOVER BLACKWATER RIVER 11 ANDOVER HIGHLAND LAKE 11 ANDOVER HOPKINS POND 11 ANTRIM WILLARD POND 1 AUBURN MASSABESIC LAKE 1 1 1 1 BARNSTEAD SUNCOOK LAKE 1 BARRINGTON ISINGLASS RIVER 1 BARRINGTON STONEHOUSE POND 1 BARTLETT THORNE POND 1 BELMONT POUT POND 1 BELMONT TIOGA RIVER 1 BELMONT WHITCHER BROOK 1 BENNINGTON WHITTEMORE LAKE 11 BENTON OLIVERIAN POND 1 BERLIN ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 11 BRENTWOOD EXETER RIVER 1 1 BRISTOL DANFORTH BROOK 11 BRISTOL NEWFOUND LAKE 1 BRISTOL NEWFOUND RIVER 11 BRISTOL PEMIGEWASSET RIVER 11 BRISTOL SMITH RIVER 11 BROOKFIELD CHURCHILL BROOK 1 BROOKFIELD PIKE BROOK 1 BROOKLINE NISSITISSIT RIVER 11 CAMBRIDGE ANDROSCOGGIN RIVER 1 CAMPTON BOG POND 1 CAMPTON PERCH POND 11 CANAAN CANAAN STREET LAKE 11 CANAAN INDIAN RIVER 11 NH Trout Stocking - April 2018 Town WaterBody 3/26‐3/30 4/02‐4/06 4/9‐4/13 4/16‐4/20 4/23‐4/27 4/30‐5/04 CANAAN MASCOMA RIVER, UPPER 11 CANDIA TOWER HILL POND 1 CANTERBURY SPEEDWAY POND 1 CARROLL AMMONOOSUC RIVER 1 CARROLL SACO LAKE 1 CENTER HARBOR WINONA LAKE 1 CHATHAM BASIN POND 1 CHATHAM LOWER KIMBALL POND 1 CHESTER EXETER RIVER 1 CHESTERFIELD SPOFFORD LAKE 1 CHICHESTER SANBORN BROOK -

Shaker Church Family Cow Barn " HABS Wo. NH-192 East Side of State Route *+A, 3 Miles South of U.S

Shaker Church Family Cow Barn " HABS Wo. NH-192 East side of State Route *+A, 3 miles south of U.S. Route h, on Mas coma Lake \J A r;--- Enfield Vicinity ' .'/." Graf tort County ^ "-< s \ Nev Hampshire /" . c::K •. r-; > i PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS Historic American Buildings Survey Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 202^3 10- HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY HABS No. NH-192 SHAKER CHURCH FAMILY COW BARN Location: East side of State Route 4A, 3 miles south of U.S. Route 4, on Mascoma Lake, Enfield Vicinity, Grafton County, New Hampshire. USGS Mascoma Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 18.730210.4833375. Present Owner; The Brewfield Trust, Maiden Trust Company, Maiden, Massachusetts. Present Occupant: The Missionaries of Our Lady of La Salette, Immaculate Heart of Mary Province. Present Use: Light agricultural use, such as storing small amounts of grain and hay and agricultural machinery; also used for other storage. Significance The Shaker Church Family Cow Barn, built in 1854, as noted in polychrome slate on the roof, is one of the largest remaining Shaker barns. It was designed and constructed in the simple, functional manner • characteristic of Shaker structures. Traditional in its construction methods, the barn had an innovative plan designed for maximum convenience and efficiency. New machinery and dairy practices were introduced here to improve the products and increase productivity. Although altered, the barn retains many original features. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History: 1. Date of erection: Preparations began in 1853; the barn was constructed in 1854, as noted in polychrome slate on the roof. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Insect Survey of Four Longleaf Pine Preserves

A SURVEY OF THE MOTHS, BUTTERFLIES, AND GRASSHOPPERS OF FOUR NATURE CONSERVANCY PRESERVES IN SOUTHEASTERN NORTH CAROLINA Stephen P. Hall and Dale F. Schweitzer November 15, 1993 ABSTRACT Moths, butterflies, and grasshoppers were surveyed within four longleaf pine preserves owned by the North Carolina Nature Conservancy during the growing season of 1991 and 1992. Over 7,000 specimens (either collected or seen in the field) were identified, representing 512 different species and 28 families. Forty-one of these we consider to be distinctive of the two fire- maintained communities principally under investigation, the longleaf pine savannas and flatwoods. An additional 14 species we consider distinctive of the pocosins that occur in close association with the savannas and flatwoods. Twenty nine species appear to be rare enough to be included on the list of elements monitored by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (eight others in this category have been reported from one of these sites, the Green Swamp, but were not observed in this study). Two of the moths collected, Spartiniphaga carterae and Agrotis buchholzi, are currently candidates for federal listing as Threatened or Endangered species. Another species, Hemipachnobia s. subporphyrea, appears to be endemic to North Carolina and should also be considered for federal candidate status. With few exceptions, even the species that seem to be most closely associated with savannas and flatwoods show few direct defenses against fire, the primary force responsible for maintaining these communities. Instead, the majority of these insects probably survive within this region due to their ability to rapidly re-colonize recently burned areas from small, well-dispersed refugia. -

Butterflies and Moths of Brevard County, Florida, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

New Hampshire River Protection and Energy Development Project Final

..... ~ • ••. "'-" .... - , ... =-· : ·: .• .,,./.. ,.• •.... · .. ~=·: ·~ ·:·r:. · · :_ J · :- .. · .... - • N:·E·. ·w··. .· H: ·AM·.-·. "p• . ·s;. ~:H·1· ··RE.;·.· . ·,;<::)::_) •, ·~•.'.'."'~._;...... · ..., ' ...· . , ·....... ' · .. , -. ' .., .- .. ·.~ ···•: ':.,.." ·~,.· 1:·:,//:,:: ,::, ·: :;,:. .:. /~-':. ·,_. •-': }·; >: .. :. ' ::,· ;(:·:· '5: ,:: ·>"·.:'. :- .·.. :.. ·.·.···.•. '.1.. ·.•·.·. ·.··.:.:._.._ ·..:· _, .... · -RIVER~-PR.OT-E,CT.10-N--AND . ·,,:·_.. ·•.,·• -~-.-.. :. ·. .. :: :·: .. _.. .· ·<··~-,: :-:··•:;·: ::··· ._ _;· , . ·ENER(3Y~EVELOP~.ENT.PROJ~~T. 1 .. .. .. .. i 1·· . ·. _:_. ~- FINAL REPORT··. .. : .. \j . :.> ·;' .'·' ··.·.· ·/··,. /-. '.'_\:: ..:· ..:"i•;. ·.. :-·: :···0:. ·;, - ·:··•,. ·/\·· :" ::;:·.-:'. J .. ;, . · · .. · · . ·: . Prepared by ~ . · . .-~- '·· )/i<·.(:'. '.·}, •.. --··.<. :{ .--. :o_:··.:"' .\.• .-:;: ,· :;:· ·_.:; ·< ·.<. (i'·. ;.: \ i:) ·::' .::··::i.:•.>\ I ··· ·. ··: · ..:_ · · New England ·Rtvers Center · ·. ··· r "., .f.·. ~ ..... .. ' . ~ "' .. ,:·1· ,; : ._.i ..... ... ; . .. ~- .. ·· .. -,• ~- • . .. r·· . , . : . L L 'I L t. ': ... r ........ ·.· . ---- - ,, ·· ·.·NE New England Rivers Center · !RC 3Jo,Shet ·Boston.Massachusetts 02108 - 117. 742-4134 NEW HAMPSHIRE RIVER PRO'l'ECTION J\ND ENERGY !)EVELOPMENT PBOJECT . -· . .. .. .. .. ., ,· . ' ··- .. ... : . •• ••• \ ·* ... ' ,· FINAL. REPORT February 22, 1983 New·England.Rivers Center Staff: 'l'bomas B. Arnold Drew o·. Parkin f . ..... - - . • I -1- . TABLE OF CONTENTS. ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEMBERS . ~ . • • . .. • .ii EXECUTIVE -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Clicking Caterpillars: Acoustic Aposematism in Antheraea Polyphemus and Other Bombycoidea Sarah G

993 The Journal of Experimental Biology 210, 993-1005 Published by The Company of Biologists 2007 doi:10.1242/jeb.001990 Clicking caterpillars: acoustic aposematism in Antheraea polyphemus and other Bombycoidea Sarah G. Brown1, George H. Boettner2 and Jayne E. Yack1,* 1Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, K1S 5B6, Canada and 2Plant Soil and Insect Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 21 November 2006 Summary Acoustic signals produced by caterpillars have been correlated sound production with attack, and an increase documented for over 100 years, but in the majority of in attack rate was positively correlated with the number of cases their significance is unknown. This study is the first signals produced. In addition, sound production typically to experimentally examine the phenomenon of audible preceded or accompanied defensive regurgitation. sound production in larval Lepidoptera, focusing on a Bioassays with invertebrates (ants) and vertebrates (mice) common silkmoth caterpillar, Antheraea polyphemus revealed that the regurgitant is deterrent to would-be (Saturniidae). Larvae produce airborne sounds, predators. Comparative evidence revealed that other resembling ‘clicks’, with their mandibles. Larvae typically Bombycoidea species, including Actias luna (Saturniidae) signal multiple times in quick succession, producing trains and Manduca sexta (Sphingidae), also produce airborne that last over 1·min and include 50–55 clicks. Individual sounds upon attack, and that these sounds precede clicks within a train are on average 24.7·ms in duration, regurgitation. The prevalence and adaptive significance of often consisting of multiple components. Clicks are audible warning sounds in caterpillars is discussed. -

Biennial Report Forestry Division

iii Nvw 3Jtampstin BIENNIAL REPORT of the FORESTRY DIVISION Concord, New Hampshire 1953 - 1954 TABLE OF CONTENTS REPORT TO GOVERNOR AND COUNCIL 3 REPORT OF THE FORESTRY DIVISION Forest Protection Forest Fire Service 5 Administration 5 Central Supply and Warehouse Building 7 Review of Forest Fire Conditions 8 The 1952 Season (July - December) 8 The 1953 Season 11 The 1954 Season (January - June) 19 Fire Prevention 21 Northeastern Forest Fire Protection Commission 24 Training of Personnel 24 Lookout Station Improvement and lVlaintenance 26 State Fire Fighting Equipment 29 Town Fire Fighting Equipment 30 Radio Communication 30 Fire Weather Stations and Forecasts 32 Wood-Processing Mill Registrations 33 White Pine Blister Rust Control 34 Forest Insects and Diseases 41 Hurricane Damage—1954 42 Public Forests State Forests and Reservations 43 Management of State Forests 48 State Forest Nursery and Reforestation 53 Town Forests 60 White Mountain National Forest 60 Private Forestry County Forestry Program 61 District Forest Advisory Boards 64 Registered Arborists 65 Forest Conservation and Taxation Act 68 Surveys and Statistics Forest Research 68 Forest Products Cut in 1952 and 1953 72 Forestry Division Appropriations 1953 and 1954 78 REPORT OF THE RECREATION DIVISION 81 Revision of Forestry and Recreation Laws j REPORT To His Excellency the Governor and the Honorable Council: The Forestry and Recreation Commission submits herewith its report for the two fiscal years ending June 30, 1954. This consists of a record of the activities of the two Divisions and brief accounts of related agencies prepared by the State Forester and Director of Recrea tion and their staffs. -

SURFACE WATER SUPPLY of the UNITED STATES 1926

PLEASE DO NOT DESTROY! OR THROWAWAY THIS PUBLICATION, if you bm» no further use for it, write to the Geological Surrey at Washington and ask for a frank to return it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SURFACE WATER SUPPLY of the UNITED STATES 1926 PART I NORTH ATLANTIC SLOPE DRAINAGE BASINS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 621 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BAY LYMAN WILBUR, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 621 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY of the UNITED STATES 1926 PART I NORTH ATLANTIC SLOPE DRAINAGE BASINS NATHAN C. GROVER, Chief Hydraulic Engineer H. B. KINNISON, A. W. HARRINGTON, O. W. HARTWELL A. H. HORTON, andJ. J. DIRZULAITIS District Engineers Prepared in cooperation with the States of MAINE, NEW HAMPSHIRE, MASSACHUSETTS, NEW YORK NEW JERSEY, MARYLAND, and VIRGINIA Geological Survey, Box3l06,Cap Oklahoma CAY, UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1930 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. ----- Price 30 cents CONTENTS Page Authorization and scope of work____ _____________________________ 1 Definition of terms______________- _ __________ ___________ 2 Explanation of data___-____________-_-_--_------_-______-_-_____-- 2 Accuracy of field data and computed results._________________________ 4 Publications________ _________________-'---_-----_--____--________-_ 5 Cooperation. _____________________________________________________ 10 Division of work__________________________________________________ 11 Oaging-station records ______________________________________ -

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory

2010 Season Summary Index NEW WOFTHE~ Zone 1: Yukon Territory ........................................................................................... 3 Alaska ... ........................................ ............................................................... 3 LEPIDOPTERISTS Zone 2: British Columbia .................................................... ........................ ............ 6 Idaho .. ... ....................................... ................................................................ 6 Oregon ........ ... .... ........................ .. .. ............................................................ 10 SOCIETY Volume 53 Supplement Sl Washington ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3: Arizona ............................................................ .................................... ...... 19 The Lepidopterists' Society is a non-profo California ............... ................................................. .............. .. ................... 2 2 educational and scientific organization. The Nevada ..................................................................... ................................ 28 object of the Society, which was formed in Zone 4: Colorado ................................ ... ............... ... ...... ......................................... 2 9 May 1947 and formally constituted in De Montana .................................................................................................... 51 cember