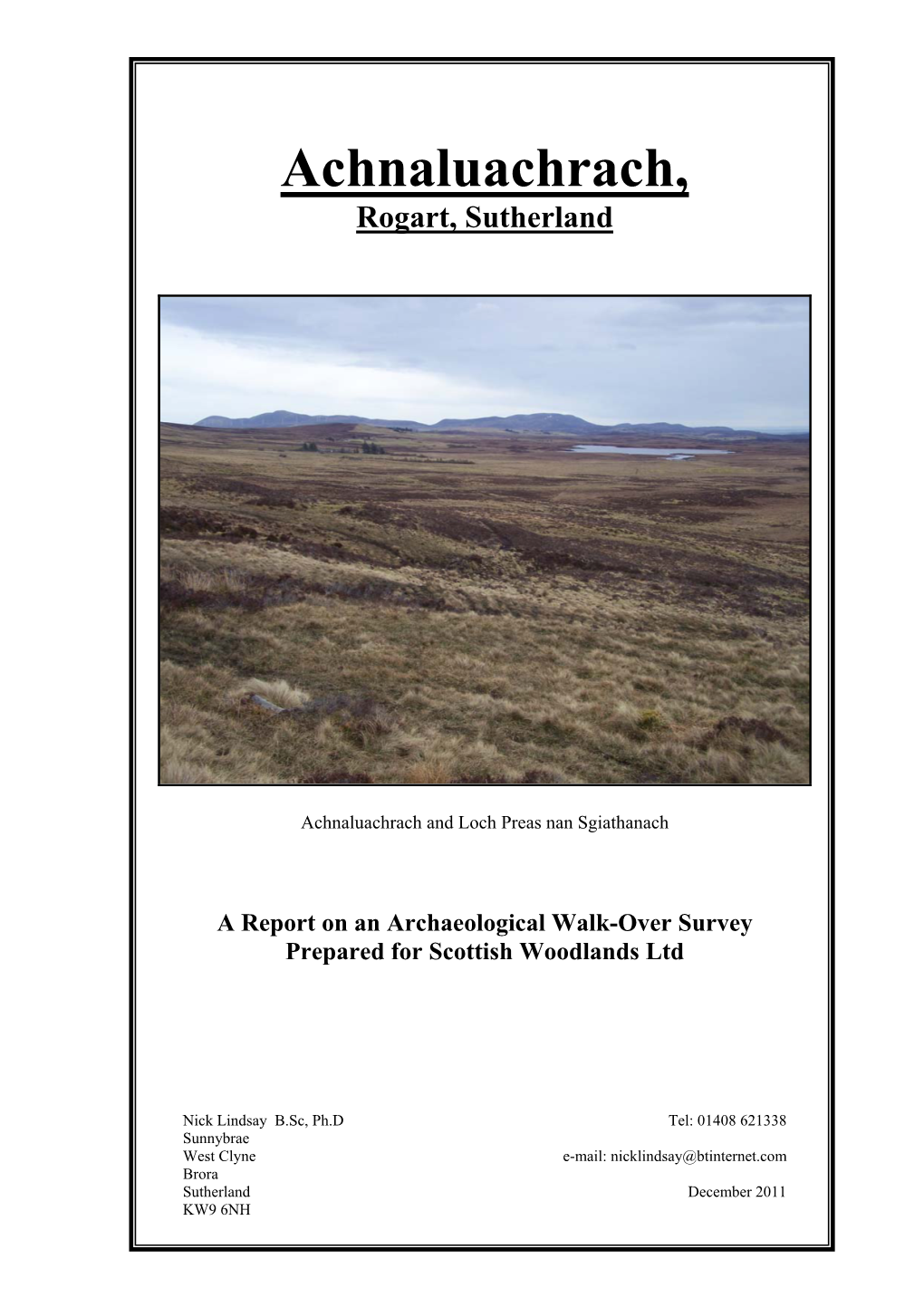

Achnaluachrach, Rogart, Sutherland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item 6. Golspie Associated School Group Overview

Agenda Item 6 Report No SCC/11/20 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Area Committee Date: 05/11/2020 Report Title: Golspie Associated School Group Overview Report By: ECO Education 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report provides an update of key information in relation to the schools within the Golspie Associated School Group (ASG) and provides useful updated links to further information in relation to these schools. 1.2 The primary schools in this area serve around 322 pupils, with the secondary school serving 244 young people. ASG roll projections can be found at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/schoolrollforecasts 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to: scrutinise and not the content of the report. School Information Secondary – Link to Golspie High webpage Primary http://www.highland.gov.uk/directory/44/schools/search School Link to School Webpage Brora Primary School Brora Primary webpage Golspie Primary School Golspie Primary webpage Helmsdale Primary School Helmsdale Primary webpage Lairg Primary School Lairg Primary webpage Rogart Primary School Rogart Primary webpage Rosehall Primary School Rosehall Primary webpage © Denotes school part of a “cluster” management arrangement Date of Latest Link to Education School Published Scotland Pages Report Golspie High School Mar-19 Golspie High Inspection Brora Primary School Apr-10 Brora Primary Inspection Golspie Primary School Jun-17 Golspie Primary Inspection Helmsdale Primary School Jun-10 Helmsdale Primary Inspection Lairg Primary School Mar-20 Lairg Primary Inspection Rogart Primary -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

Achatomlinie, Rogart, Sutherland

Achatomlinie, Rogart, Sutherland The site, with Achatomlinie shepherd’s cottage, looking south west A Report on an Archaeological Walk-Over Survey Prepared for Scottish Woodlands Ltd Nick Lindsay B.Sc, Ph.D Tel: 01408 621338 Sunnybrae West Clyne e-mail: [email protected] Brora Sutherland December 2011 KW9 6NH Achatomlinie, Rogart, Sutherland Contents 1.0 Executive Summary...................................................................................................................2 2.0 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................3 2.1 Background............................................................................................................................3 2.2 Objectives..............................................................................................................................3 2.3 Methodology..........................................................................................................................3 2.4 Limitations.............................................................................................................................3 2.5 Setting....................................................................................................................................3 3.0 Results .......................................................................................................................................5 3.1 Desk-Based Assessment........................................................................................................5 -

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015

Caithness and Sutherland Proposed Local Development Plan Committee Version November, 2015 Proposed CaSPlan The Highland Council Foreword Foreword Foreword to be added after PDI committee meeting The Highland Council Proposed CaSPlan About this Proposed Plan About this Proposed Plan The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, will form the Highland Council’s Development Plan that guides future development in Highland. The Plan covers the area shown on the Strategy Map on page 3). CaSPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the Caithness and Sutherland area over the next 10-20 years. Along the north coast the Pilot Marine Spatial Plan for the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters will also influence what happens in the area. This Proposed Plan is the third stage in the plan preparation process. It has been approved by the Council as its settled view on where and how growth should be delivered in Caithness and Sutherland. However, it is a consultation document which means you can tell us what you think about it. It will be of particular interest to people who live, work or invest in the Caithness and Sutherland area. In preparing this Proposed Plan, the Highland Council have held various consultations. These included the development of a North Highland Onshore Vision to support growth of the marine renewables sector, Charrettes in Wick and Thurso to prepare whole-town visions and a Call for Sites and Ideas, all followed by a Main Issues Report and Additional Sites and Issues consultation. -

Timetable Updated 28Th June 2021

Timetable updated 28th June 2021 Days of Operation Monday to Friday Days of Operation Saturdays Service Number 62 Service Number 62 Service Description Tain - Lairg - Golspie - Hemsldale Service Description Tain - Lairg Service No. 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 Service No. 62 62 62 62 62 Sch Sch #Sch Sch NF Sch F #Sch Tain Asda - 1003 1303 1540 - Tain Asda - - - - 1005 1305 - - 1630 - Codes: Tain Lamington Street 0800 1010 1310 1545 1830 Tain Lamington Street 0645 0701 0708 0713 1012 1312 - - 1635 1830 NF Not Fridays Edderton Bus Shelter 0810 1020 1320 1555 1840 Edderton Bus Shelter 0655 0711 0718 0723 1022 1322 - - 1645 1840 Sch Schooldays only Ardgay Community Hall 0822 1033 1332 1607 1852 Ardgay Community Hall 0707 0723 0730 0735 1035 1335 - - 1657 1852 #Sch School holidays only Migdale Hospital - - R1335 - R1853 Migdale Hospital - - - - - 1338 - - - 1855 F Fridays only Bonar Bridge Post Office 0825 1036 1336 1610 1855 Bonar Bridge Post Office 0710 0726 0733 0738 1038 1343 - - 1700 1900 Invershin 0830 1041 1341 1615 1900 Invershin 0715 0731 0738 0743 1043 1348 - - 1705 1905 Inveran Bridge - 1043 1343 1617 - Inveran Bridge - - - - 1045 1350 - - - - Achany Road End - - 1350 - - Achany Road End - - - - - 1357 - - - - Lairg Post Office 0842 1055 1357 1629 1914 Lairg Costcutter - - - 0753 - - - - - - Lairg Post Office 0727 0743 0750 0755 1057 1404 - - 1717 1917 Codes: R Operates via Migdale Hospital on request. If operates via Link Link Link Migdale bus will call at subsequent timing points up to four Lairg Post Office - - 0800 0758 1100 -

Dornoch Corrwruni:Ty Association Per Mr PG Wild DORNOCH GOLSPIE

SUTHERLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL District Offices Main Street GOLSPIE Dornoch Corrwruni:tY Association 28 November 1983 Per Mr PG Wild The Meadows DORNOCH Dear Sir/ Madam LOTTERIES AND il11USEMENTS ACT 1976 REGISTR.i ION OF SOCIEl'Y I wish to draw your attention to Schedule 1 and Paragraph 9 of the above named Act where it is stated that every Society which is registered under the Act shall pay to the Local Authority on the first day of January in each yea:r, while it is so registered., th~ fee poryable which is £10. I have also to draw your attention to Schedule 1 and Paragraph 8 of the Act where it states that a Society 1hich is for the time being registered under this Act may, at any time, apply to the Local Authority for the cancellation of the registration. If you do not wish your Society to be registered during the year 1984 please let me know within 14 days . I have also to refer to Schedule 1 (Part II) of the Act which requires the promoter of the lottery to submit, not later than the end of the third month in which the winners o.f prizes in the lottery are ascer tained, a return certif"ed by two members of the Society who have been appointed by the Society to certify that the return is correct. Please ensure that any return oustanding is now submitted to me . Yours faithfully Chief Executive Enc SCOTTISH EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ij}J New St Andrew's House Edinburgh EH1 3SY Telephone 031-556 8400 ext 4229 Telex 727301 •PG Wild Esq Please reply to The Secretary Secretary Your reference Royal Burgh o[ Dornoch & District Community Association Our reference The Meadows JTF/A/H87 DORNOCH IV25 3SF Date g February 1984 Dear Sir FURTHER EDUCATION (SCOTLAND) REGULATIONS 1959 CAPITAL GRANTS TO APPROVED ASSOCIATIONS ROYAL BURGH OF DORNOCH & DISTRICT COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION I refe r to the Department's letter dated 2.9 August 1980 offering grant in terms o[ the Further Education (Scotland) Regulations 1959. -

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol

Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies Vol. 22 : Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies 1 Vol. 22: Cataibh an Ear & Gallaibh (East Sutherland & Caithness) Author: Kurt C. Duwe 2nd Edition January, 2012 Executive Summary This publication is part of a series dealing with local communities which were predominantly Gaelic- speaking at the end of the 19 th century. Based mainly (but not exclusively) on local population census information the reports strive to examine the state of the language through the ages from 1881 until to- day. The most relevant information is gathered comprehensively for the smallest geographical unit pos- sible and provided area by area – a very useful reference for people with interest in their own communi- ty. Furthermore the impact of recent developments in education (namely teaching in Gaelic medium and Gaelic as a second language) is analysed for primary school catchments. Gaelic once was the dominant means of conversation in East Sutherland and the western districts of Caithness. Since the end of the 19 th century the language was on a relentless decline caused both by offi- cial ignorance and the low self-confidence of its speakers. A century later Gaelic is only spoken by a very tiny minority of inhabitants, most of them born well before the Second World War. Signs for the future still look not promising. Gaelic is still being sidelined officially in the whole area. Local council- lors even object to bilingual road-signs. Educational provision is either derisory or non-existent. Only constant parental pressure has achieved the introduction of Gaelic medium provision in Thurso and Bonar Bridge. -

Come Walk in the Footsteps of Your Ancestors

Come walk in the footsteps of your ancestors Come walk in the footsteps Your Detailed Itinerary of your ancestors Highland in flavour. Dunrobin Castle is Museum is the main heritage centre so-called ‘Battle of the Braes’ a near Golspie, a little further north. The for the area. The scenic spectacle will confrontation between tenants and Day 1 Day 3 largest house in the northern Highlands, entrance you all the way west, then police in 1882, which was eventually to Walk in the footsteps of Scotland’s The A9, the Highland Road, takes you Dunrobin and the Dukes of Sutherland south, for overnight Ullapool. lead to the passing of the Crofters Act monarchs along Edinburgh’s Royal speedily north, with a good choice of are associated with several episodes in in 1886, giving security of tenure to the Mile where historic ‘closes’ – each stopping places on the way, including the Highland Clearances, the forced crofting inhabitants of the north and with their own story – run off the Blair Castle, and Pitlochry, a popular emigration of the native Highland Day 8 west. Re-cross the Skye Bridge and main road like ribs from a backbone. resort in the very centre of Scotland. people for economic reasons. Overnight continue south and east, passing Eilean Between castle and royal palace is a Overnight Inverness. Golspie or Brora area. At Braemore junction, south of Ullapool, Donan Castle, once a Clan Macrae lifetime’s exploration – so make the take the coastal road for Gairloch. This stronghold. Continue through Glen most of your day! Gladstone’s Land, section is known as ‘Destitution Road’ Shiel for the Great Glen, passing St Giles Cathedral, John Knox House Day 4 Day 6 recalling the road-building programme through Fort William for overnight in are just a few of the historic sites on that was started here in order to provide Ballachulish or Glencoe area. -

The Scottish Highlanders and the Land Laws: John Stuart Blackie

The Scottish Highlanders and the Land Laws: An Historico-Economical Enquiry by John Stuart Blackie, F.R.S.E. Emeritus Professor of Greek in the University of Edinburgh London: Chapman and Hall Limited 1885 CHAPTER I. The Scottish Highlanders. “The Highlands of Scotland,” said that grand specimen of the Celto-Scandinavian race, the late Dr. Norman Macleod, “ like many greater things in the world, may be said to be well known, and yet unknown.”1 The Highlands indeed is a peculiar country, and the Highlanders, like the ancient Jews, a peculiar people; and like the Jews also in certain quarters a despised people, though we owe our religion to the Hebrews, and not the least part of our national glory arid European prestige to the Celts of the Scottish Highlands. This ignorance and misprision arose from several causes; primarily, and at first principally, from the remoteness of the situation in days when distances were not counted by steam, and when the country, now perhaps the most accessible of any mountainous district in Europe, was, like most parts of modern Greece, traversed only by rough pony-paths over the protruding bare bones of the mountain. In Dr. Johnson’s day, to have penetrated the Argyllshire Highlands as far west as the sacred settlement of St. Columba was accounted a notable adventure scarcely less worthy of record than the perilous passage of our great Scottish traveller Bruce from the Red Sea through the great Nubian Desert to the Nile; and the account of his visit to those unknown regions remains to this day a monument of his sturdy Saxon energy, likely to be read with increasing interest by a great army of summer perambulators long after his famous dictionary shall have been forgotten, or relegated as a curiosity to the back shelves of a philological library. -

Notes of A9 Safety Group Meeting on 18 April 2019

A9 Safety Group 18th April 2019 at 11:00 Tulloch Caledonian Stadium, Inverness. Marco Bardelli Transport Scotland Donna Turnbull Transport Scotland Stuart Wilson Transport Scotland Richard Perry Transport Scotland David McKenzie Transport Scotland Sam McNaughton Transport Scotland Chris Smith A9 Luncarty to Birnam, Transport Scotland Michael McDonnell Road Safety Scotland Kenny Sutherland Northern Safety Camera Unit Martin Reid Road Haulage Association Fraser Grieve Scottish Council for Development & Industry David Richardson Federation of Small Businesses Alan Campbell BEAR Scotland Ltd Kevin McKechnie BEAR Scotland Ltd Notes of Meeting 1. Welcome & Introductions. Stuart Wilson welcomed all to the meeting followed by a round table introduction from everybody present. Stuart Wilson provided high level accident and casualty trends on the A9 and identified that sustaining the momentum in accident reduction activity was still a key priority but that driving down accident numbers was very challenging. He elaborated that fatigue on the A9 was a serious issue and any measures which could reduce accident risk associated with fatigue should be considered. 2. Apologies Apologies were made for Morag MacKay (TS), Aaron Duncan (SCP), Chic Haggart (PKC) 3. Previous Minutes and Actions The minutes were accepted as a true reflection of the previous meeting. SW and DT are continuing to investigate the research that would be required to allow the consideration of a change to the national speed limit for vans and will provide an update on this at future meetings Action: Transport Scotland will consider the research required to determine the impact of a change to the national speed limits for vans. 4. Average Speed Camera System Update. -

Gordonbush Wind Farm Case Study

Gordonbush community funds The Gordonbush fund provides approx In addition, Gordonbush Wind Farm has About the proposed Working for a £200K each year for the community also provided £160,000 of funding towards council areas of Brora, Golspie, Helmsdale a new state of the art all-weather multi-use Gordonbush extension fairer Scotland and Rogart. Since 2011 it has granted over sports pitch in Golspie. £514,000 to community and charitable groups and projects in these areas. An application has been submitted to the Scottish SSE is also working hard to help make a fairer £200K average annual fund Government for a proposed 16 turbine extension Scotland. It does this by helping local communities to the south-west of the existing Gordonbush Wind to realise opportunities for growth at the local level total funds awarded since 2011 £514K Farm site. and by supporting national initiatives to encourage 136 projects funded since 2011 sustainable economic growth across Scotland. The proposed extension has been carefully 25 year project lifespan designed to minimise visibility from the surrounding As a responsible UK company, SSE wants to be as landscape, particularly Strath Brora, and also transparent as possible about the contribution it is £5.5M+ total funding 2011-2036 maximise the existing infrastructure on site. making to society. In 2014 SSE was the first FTSE Gordonbush 100 company to be awarded the fair tax mark. Brora Angling Club SSE held two public exhibitions in 2013 and 2015 Received £5,000 to purchase a new boat to gain feedback on the proposal from the Wind Farm community before submitting it’s application. -

Abbie Is a Star Karter

War and wildlife on Abbie is a the Moray Firth star karter Active Outdoors Page 20 Page 4 AND WEEKLY JOURNAL FOR SUTHERLAND AND THE NORTH FOUNDED 1899 FRIDAY, APRIL 25, 2014 www.northern-times.co.uk £1 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: 75p INSIDE THIS WEEK’S NORTHERN Fresh fight TIMES PETS over wind farm plan By Caroline McMorran reports the Tressady develop- either individually or cumu- [email protected] ment would be visible at all latively with other operational points of the compass within a developments.” OBJECTORS to the controver- 3km radius. But members of the coun- sial Tressady wind farm project Those against are concerned cil’s north planning committee are gearing up for a fresh fight. about the visual impact, noise went against planners’ recom- The plan to erect 13 tur- nuisance and effect on tour- mendation, and voted seven to Pip is Pet of Month bines, each 115 metres high, ism, among other issues. two against the development Page 19 to the north west of Rogart, Alastair Gilchrist, East following a site visit. was rejected earlier this year Langwell, objected to the origi- Councillors were swayed by by Highland Council’s north nal Tressady application. East Sutherland and Edderton planning committee He said: “We’re within a mile member Graham Phillips who ARTS But the power company from the nearest turbine to our had demanded a visit be made behind the project, Wind house. to the area before a decision Prospect Developments, are “When I look out my house was taken. now appealing that decision, just now I can see three tur- Councillor Phillips said he You don’t have to be it was officially confirmed this bines at Lairg.