A Transformation of Art Into Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRUEBA DE ACCESO Y ADMISIÓN a LA UNIVERSIDAD LENGUA EXTRANJERA ANDALUCÍA, CEUTA, MELILLA Y CENTROS En MARRUECOS (INGLÉS) CURSO 2019-2020

PRUEBA DE ACCESO Y ADMISIÓN A LA UNIVERSIDAD LENGUA EXTRANJERA ANDALUCÍA, CEUTA, MELILLA y CENTROS en MARRUECOS (INGLÉS) CURSO 2019-2020 Instrucciones: a) Duración: 1 hora y 30 minutos. b) Este examen consta de varios bloques. Debe responder a las preguntas que se indican en cada uno. c) La puntuación está indicada en cada uno de los apartados. d) No se permite el uso de diccionario. El examen consta de 3 Bloques (A, B y C) En cada bloque (Comprehension, Use of English y Writing) se plantean varias preguntas, de las que se deberá responder al número que se indica en cada uno. En caso de responder más cuestiones de las requeridas, serán tenidas en cuenta las respondidas en primer lugar hasta alcanzar dicho número. Las preguntas han de ser respondidas en su totalidad: si la pregunta tiene dos secciones, hay que responder ambas. BLOQUE A (Comprensión lectora) Puntuación máxima: 4 puntos Debe responderse a las 8 preguntas de uno de los 2 textos propuestos. I * COMPREHENSION (4 points). CHOOSE TEXT 1 OR TEXT 2 AND ANSWER ALL THE QUESTIONS FROM THAT TEXT ONLY. TEXT 1: FASHION AND WASTE 1 In 2018, beauty vlogger Samantha Ravndahl announced to her legion of subscribers that she would no longer accept 2 promotional samples because she was concerned about the waste in the packaging of beauty and fashion items. She was trying 3 to combat not just her own waste, but that of all her followers. 4 It’s really a game of chicken or the egg to decide who is to blame for the culture of waste: social media or fashion itself? The 5 answer is a toxic combination of both. -

The Issues and Benefits of an Intelligent Design Observatory

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN CONFERENCE - DESIGN 2008 Dubrovnik - Croatia, May 19 - 22, 2008. THE ISSUES AND BENEFITS OF AN INTELLIGENT DESIGN OBSERVATORY B.J. Hicks, H.C. McAlpine, P. Törlind, M. Štorga, A. Dong and E. Blanco Keywords: design process, design teams, design performance, observational studies, experimental data, experimental methodology 1. Introduction Central to improving and sustaining high levels of innovative design is the fundamental requirement to maximise and effectively manage design performance. Within the context of 21st century design - where the process is largely digital, knowledge-driven and highly distributed - this involves the creation of tailored design processes, the use of best-performing tool sets, technology mixes and complementary team structures. In order to investigate these aspects, there is a need to evaluate the practices and needs of industry; advance understanding and design science; create new tools, methods and processes; and assess the state-of-the-art technology and research output. However, effective investigation of these four areas can only be achieved through a fundamental understanding of today’s complex, dynamic design environments. Such detailed understanding is presently unavailable or at least very difficult to obtain. This is largely because of a lack of capability for holistic investigation of the design process and an inability to perform controlled experiments, using reliable and meaningful metrics that generate complete high quality data. The consequences of this are that many tools, methods or technologies that could benefit industry are not adopted, some are adopted without rigorous assessment and do not perform as anticipated, and many are developed on the basis of incomplete or limited data. -

Effective New Product Ideation: IDEATRIZ Methodology

Effective New Product Ideation: IDEATRIZ Methodology Marco A. de Carvalho Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná, Mechanical Engineering Department, Av. Sete de Setembro 3165, 80230-901 Curitiba PR, Brazil [email protected] Abstract. It is widely recognized that innovation is an activity of strategic im- portance. However, organizations seeking to be innovative face many dilem- mas. Perhaps the main one is that, though it is necessary to innovate, innovation is a highly risky activity. In this paper, we explore the origin of product innova- tion, which is new product ideation. We discuss new product ideation ap- proaches and their effectiveness and provide a description of an effective new product ideation methodology. Keywords: Product Development Management, New Product Ideation, TRIZ. 1 Introduction Introducing new products is one of the most important activities of companies. There is a significant correlation between innovative firms and leadership status [1]. On the other hand, evidence shows that most of the new products introduced fail [2]. There are many reasons for market failures of new products. This paper deals with one of the main potential sources for success or failure in new products: the quality of new product ideation. Ideation is at the start of product innovation, as recognized by eminent authors in the field such as Cooper [1], Otto & Wood [3], Crawford & Di Benedetto [4], and Pahl, Beitz et al. [5]. According to the 2005 Arthur D. Little innovation study [6], idea management has a strong impact on the increase in sales associated to new products. This impact is measured as an extra 7.2 percent of sales from new products and makes the case for giving more attention to new product ideation. -

Reverse Metadesign: Pedagogy and Learning Tools for Teaching the Fashion Collection Design Process Online

7th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’21) Universitat Politecnica` de Valencia,` Valencia,` 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/HEAd21.2021.13181 Reverse Metadesign: Pedagogy and Learning Tools for Teaching The Fashion Collection Design Process Online Daria Casciani, Chiara Colombi, Federica Vacca Design Department, Politecnico di Milano, Italy. Abstract The present article discusses the experience of redesigning the pedagogy and learning tools of a pillar course at the School of Design of Politecnico di Milano, the Metadesign studio course. Metadesign is a design methodology that leads to the concept definition of a new product or service through a research process that synthesizes design goals, technological and productive constraints, market context, and consumption trends for a consumers’ group of reference. It represents a unique methodological approach characterizing a design education as it provides a consolidated research practice able to support the design process. The course structure foresees the reconstruction in phases and the development of all the contextual elements—product, space, service, communication artifact, etc.—that come into relation with the to-be- designed object and influence its characteristics. This process enables creating the "abacus" of components to use in a design activity. Considering the ever- increasing need to reshape the whole education system because of the paradigmatic change pushed by digital transformation and the urgency for on- distance courses posed by the COVID-19 emergency, the article presents a renewed "reversed" course structure. It highlights strengths and opportunities for further improvements representing a solid base for innovating a fashion design education. Keywords: Metadesign; fashion design; learning-by-doing; reflection-in- action; deductive reflection; virtual learning environments. -

Designing Your Life How to Build a Well- Lived, Joyful Life Bill Burnett and Dave Evans

Designing Your Life How to Build a Well- Lived, Joyful Life Bill Burnett and Dave Evans ALFREDSUPPLEMENTAL A. KNOPF GRAPHICSNEW YORK 2016 COPYRIGHT © 2016 BY WILLIAM BURNETT AND DAVID J. EVAN Burn_9781101875322_3p_all_r1.j.indd 3 6/14/16 2:20 PM Contents 1. Try Stuff: Health/Work/Play/Love Dashboard 1 2. Try Stuff: Workview and Lifeview 6 3. Try Stuff: Good Time Journal 9 4. Try Stuff: Mind Mapping 13 5. Try Stuff: Odyssey Plan 20 6. Try Stuff: Prototyping 29 7. Try Stuff: Reframing Failure 37 8. Try Stuff: Building a Team 41 Try Stuff Health/Work/Play/Love Dashboard 1. Write a few sentences about how it’s going in each of the four areas. 2. Mark where you Tryare (0Stuff to Full) on each gauge. 3. Ask yourself if there’s a design problem you’d Health/Work/Play/LoveTry Stuff Dashboard like to tackle in any of these areas. Health/Work/Play/Love Dashboard 4. Now ask yourself if your “problem” is a gravity 1. Write a few sentences about how it’s going in problem. 1. Weachrite ofa fewthe foursentences areas. about how it’s going in 2. eachMark ofwher thee four you areas.are (0 to Full) on each gauge. 2.3. MarkAsk yourself where youif ther aree’s (0 a to design Full) on problem each gauge. you’d 3. Asklike toyourself tackle ifin ther anye’s of athese design areas. problem you’d 4. likeNow to ask tackle yourself in any if yourof these “problem” areas. is a gravity 4. Nowproblem. -

Brainstagram: Presenting Diverse Visually Inspiring Stimuli for Creative Design

Brainstagram: Presenting Diverse Visually Inspiring Stimuli For Creative Design Grace Yu-Chun Yen Wei-Tze Tsai Abstract Computer Science Computer Science This paper presents Brainstagram, a web-based tool University of Illinois University of Illinois leveraging the structure of social networks to assist 201 N. Goodwin Avenue 201 N. Goodwin Avenue designers in finding inspiration. One challenge Urbana, IL 61801 Urbana, IL 61801 designers face when brainstorming is knowing how to [email protected] [email protected] search for unlikely sources of inspiration. In our study we present designers with Brainstagram, which Jessica L. Mullins Ranjitha Kumar organizes visual stimuli through tag co-occurrence to Computer Science Computer Science display related concepts. This allows users to easily University of Illinois University of Illinois navigate from relevant to unexpected images. In this 201 N. Goodwin Avenue 201 N. Goodwin Avenue pilot study, 6 participants generated 29 different Urbana, IL 61801 Urbana, IL 61801 designs which were evaluated on creativity and [email protected] [email protected] diversity. Our study demonstrates Brainstagram as a potentially effective tool in the brainstorming process. Author Keywords Copyright is held by the author/owner(s). Creativity; Inspiration; Brainstorming; Design; Social CHI 2015, April 18 – 23, 2015, Seoul, Korea. Media ACM ACM Classification Keywords H.3.3 [Information Storage and Retrieval]: Information Search and Retrieval --- Search process, Selection process; H.5.2 [User Interfaces]: Information and Presentation --- User-centered design. Introduction related to the user’s specific design task. These stimuli Ideation is one of the crucial stages in design process. are intended to help the designer discover new sources Previous work has shown that the originality of a design of inspiration. -

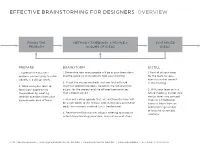

Effective Brainstorming for Designers Overview

EFFECTIVE BRAINSTORMING FOR DESIGNERS OVERVIEW FOCUS THE METHOD + TIMEBOXES x PEOPLE = SYNTHESIZE PROBLEM VOLUME OF IDEAS IDEAS PREPARE BRAINSTORM DISTILL 1. Agree on the business 1. Determine how many people will be in your brainstorm, 1. Post all of your ideas problem you’re trying to solve and the space you’ll be able to hold your meeting. for the team to see— (ideally in a design brief). even those that weren’t 2. Select the design methods that you feel will yield in the meeting. 2. Work with your team to the most appropriate ideas, based on the required final focus your approach to output for the project and the different personalities 2. With your team or in a the problem by creating that will be involved. future meeting, cluster your ideation questions from your design ideas into concept agreed-upon area of focus. 3. Plan out a clear agenda that sets out how the time will maps as a timeboxed be used—down to the minute, with stated idea generation exercise. Move from an goals for everyone involved (a.k.a. timeboxing). overwhelming number of ideas to systematic 4. Reserve the final minutes of your meeting to establish solutions. criteria for evaluating your ideas and outline next steps. ©2012 DAVID SHERWIN | [email protected] | CHANGEORDERBLOG.COM | @CHANGEORDER | ALL RIGHTS RESERVED PREPARING FOR A BRAINSTORM: IDEATION QUESTIONS Let’s start coming up with all sorts of amazing ideas! Wait—where do we even start? First, jot down some ideation questions. They are restatements of issues that form the basis of a design problem. -

Using Creativity Techniques in the Product-Innovation Process

61-03-83 USING CREATIVITY TECHNIQUES IN THE PRODUCT-INNOVATION PROCESS Horst Geschka uring the process of product innovation, numerous problems that require creative solutions are encountered. These problems include D recognizing of customer needs, generating ideas for new products or product applications, developing new product concepts, finding solutions for technical problems, adjusting the production process, and developing a marketing concept for the market launch. A number of solutions may be developed for each of these problems. Through screening and evaluation, the best solutions serve as a point of departure for the next step in the product-innovation process (see Exhibit 1). Solutions can be found by means of technical know-how and experience. However, solutions can also be developed systematically by applying creativity techniques. New product ideas often result from the efforts of a few highly creative individuals whose brilliant ideas are turned into new products. Although this method of developing new product ideas is often successful, an organization cannot merely depend on a few highly creative individuals. The reasons for this are: Only a limited number of people within an organization can be labelled “highly creative.” Experience shows that within certain professions less than 10% of the people can be indicated as highly creative. This means that when these people are the only ones that an organization can depend on, the production of useful ideas is rather limited. New products are now being developed systematically. Because the process of product development has a fixed sequence, creative input is required at certain fixed moments in the process. Therefore, a company must be able HORST GESCHKA is the founder of Geschka & Partner Management Consultants and professor at the Technical University of Darmstadt, Germany. -

The Creativity Exploration, Through the Use Of

THE CREATIVITY EXPLORATION, THROUGH THE USE OF BRAINSTORMING TECHNIQUE, ADAPTED TO THE PROCESS OF CREATION IN FASHION KARLA MAZZOTTI1, ANA CRISTINA BROEGA2, LUIZ VIDAL NEGREIROS GOMES3 1Universidade do Minho, Mestranda em Comunicação de Moda, [email protected] 2Universidade do Minho, Professora Doutora, [email protected] 3Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Professor Doutor, [email protected] Abstract: This article describes a practical work experience in a classroom, which deals with aggregating techniques that facilitate the development of creativity, in a process of fashion creation. The method used was adapted to the fashion design, through the use of the concept of "brainstorming" and his approach to generating multiple ideas. The aim of this study is to analyze the creative performance of the students, and the creative possibilities resulting from the use and adaptation of this creative technique. Keywords: creativity; creative process; brainstorming; lateral thinking. 1. Introduction The present study was developed from a work in the curricular unit of Fashion Design Collections in the course of Fashion Design and Marketing, from the University of Minho, in the second semester of 2012. The objectify of the project was to develop a mini-collection of Tops11, from the use of brainstorming techniques, such as the influential variable in the creative process. The focus of this work is the exploration of creativity as a factor essential for innovation and idea generation, in both the academic and professional level. Historically, the creator potential of man began to have importance at the time of the Renaissance, when appear the individualism and, in a sense of value, individuality was seeking of override the social (Ostrower, 2010). -

Brainstorming, Ideation, and Design Elijah Wiegmann

Brainstorming, Ideation, and design Elijah Wiegmann Founder Base Design Studio 4moms Design Director Michael Graves Design Group What is “design thinking” ? UNCERTAINTY FOCUS research prototype design Designers like ambiguity We’re sensitive artists We’re sensitive artists “That Blue isn’t blue enough” It’s actually a bit more Cerulean than Teal “What if it wasn’t?” Blow it up! Get it out of my face! “Does it have to be like that?” I just, like... don’t get it But we’re also Canaries This is the part where you get sensitive... Have you actually tested? Do you want the truth? Are your costs in-line? What’s it made out of? Who can help us? Does it work? Does anyone even want it? The Process The Process question/hypothesis Test quickly iterate FOCUS Exercises question/hypothesis STORYBOARDING THAT MAKES ME THINK OF... CONNECTIONS WISHING S.C.A.M.P.E.R ZERO DRAFT BRAIN WRITING question/hypothesis https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/creative-exercises-better-than-brainstorming CONNECTIONS question/hypothesis https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/creative-exercises-better-than-brainstorming THAT MAKES ME THINK OF... question/hypothesis https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/creative-exercises-better-than-brainstorming WISHING... It would be so much easier if we didn’t have to worry about (x)... question/hypothesis https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/creative-exercises-better-than-brainstorming Test Quickly Iterate (refine) Focus Knowing the constraints! Charles Eames “Here is one of the few effective keys to the design problem — the ability of the designer to recognize as many of the constraints as possible — his willingness and enthusiasm for working within these constraints. -

Design Thinking for Organizations: Functional Guidelines

NordDesign 2018 August 14 – 17, 2018 Linköping, Sweden Design thinking for organizations: functional guidelines Pedro Ishio1, PhD Ricardo Gaspar2, PhD Romulo Lins3 1Pedro Ishio, student at the The Graduate Program in Engineering and Innovation Management at the Federal University of ABC [email protected] 2PhD Ricardo Gaspar, College Mayor and Associate Professor at the Federal University of ABC [email protected] 3 PhD Romulo Gonçalves Lins, Professor at the Engineering, Modelling and Applied Sciences Center at the Federal University of ABC [email protected] Abstract The objective of this paper is to propose functional guidelines for the assertive practice of the design thinking approach in organizational environments, and therefore to promote innovation. Considering the statement that contextual conditions directly influence innovation, a literature review is conducted in both design thinking and organizational structures bodies of knowledge in order to discover possible relationships between one another. A brief explanation about how designers make sense of things is presented in order to exploit connections between design thinking, creativity, and innovation, and after three specific organizational structures – formalization, hierarchy and functional differentiation – are analyzed, relationships between them and design thinking are established. Accordingly, three functional guidelines for organizations to exercise design thinking assertively are proposed: in terms of formalization, employees must be provided -

Design Thinking

cover_OK.qxd 9/24/09 04:08 PM Page 1 Title: Basic Design-Thinking__Cover Client: QPL Size: 491mmx230mm Publisher’s note BASICS BASICS Gavin Ambrose Design Design Paul Harris Gavin Ambrose/Paul Harris Gavin Ambrose/Paul Basics Ethical practice is well known, taught Featured topics 08 The Basics Design series from 08 Gavin Ambrose studied at Central and discussed in the domains of brainstorming AVA Publishing’s Academia imprint St Martins and is a practising graphic defining the design problem medicine, law, science and sociology design directions explores key areas of design Design 08 designer. Current commercial practice but was, until recently, rarely idea generation through a series of case studies includes clients from the arts sector, discussed in the terms of the Applied implementation juxtaposed by key creative ‘basics’. galleries, publishers and advertising models Visual Arts. Yet design is becoming Contemporary work is supported DESIGN agencies. He is the co-author/designer prototyping an increasingly integral part of quantitative and qualitative by concise descriptions, technical of several books on branding, our everyday lives and its influence researching the design expansions and diagrammatic packaging and editorial design. problem on our society ever-more prevalent. samples and feedback visualisations, enabling the reader TH!NKING selection and refinement to fully understand the work AVA Publishing believes that our sketching being discussed. Paul Harris studied at London College world needs integrity; that the target groups of Printing and is a freelance writer and ramifications of our actions upon themes The eighth in this series, Design value editor. He has written for magazines and others should be for the greatest Thinking examines the ways in visualising ideas journals both in London and New York, happiness and benefit of the greatest which solutions to a design brief are n the act or practice including Dazed & Confused.