Shift to (De)Centralisation Creates Contradiction in Policy of Managing Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solar Plus Energy Storage System at Dahod, Gujarat Traction Sub-Station by Indian Railways

SOLAR PLUS ENERGY STORAGE SYSTEM AT DAHOD, GUJARAT TRACTION SUB-STATION BY INDIAN RAILWAYS 11, January 2021 Submitted to Tetra Tech ES, Inc. (DELETE THIS BLANK PAGE AFTER CREATING PDF. IT’S HERE TO MAKE FACING PAGES AND LEFT/RIGHT PAGE NUMBERS SEQUENCE CORRECTLY IN WORD. BE CAREFUL TO NOT DELETE THIS SECTION BREAK EITHER, UNTIL AFTER YOU HAVE GENERATED A FINAL PDF. IT WILL THROW OFF THE LEFT/RIGHT PAGE LAYOUT.) SOLAR PLUS ENERGY STORAGE SYSTEM AT DAHOD, GUJARAT TRACTION SUB- STATION BY INDIA RAILWAYS Prepared for: United States Agency for International Development (USAID/India) American Embassy Shantipath, Chanakyapuri New Delhi-110021, India Phone: +91-11-24198000 Submitted by: Tetra Tech ES, Inc. A-111 11th Floor, Himalaya House, K.G. Marg, Connaught Place New Delhi-110001, India Phone: +91-11-47374000 DISCLAIMER This report is prepared for the M/s Tetra Tech ES, Inc. for the ‘assessment of the Vendor Rating Framework (VRF)’. This report is prepared under the Contract Number AID-OAA-I-13-00019/AID- OAA-TO-17-00011. DATA DISCLAIMER The data, information and assumptions (hereinafter ‘data-set’) used in this document are in good faith and from the source to the best of PACE-D 2.0 RE (the program) knowledge. The program does not represent or warrant that any dataset used will be error-free or provide specific results. The results and the findings are delivered on "as-is" and "as-available" dataset. All dataset provided are subject to change without notice and vary the outcomes, recommendations, and results. The program disclaims any responsibility for the accuracy or correctness of the dataset. -

Answered On:23.07.2001 Telecom Facilities Babubhai Khimabhai Katara;Chandresh Patel Kordia

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA COMMUNICATIONS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:217 ANSWERED ON:23.07.2001 TELECOM FACILITIES BABUBHAI KHIMABHAI KATARA;CHANDRESH PATEL KORDIA Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: (a) Whether there are still waiting list for telephone connections in Gujarat particularly Jamnagar and Dahod district of the state. (b) if so, the details thereof as on date, district wise. (c) the number of telephone connections provided during the last three years and till date, district wise. (d) the number of telephone connections proposed to be provided during 2001-2002. (e) the number of telephone exchanges set up in Jamnagar and Dahod districts during the last three years and till date, city wise; and (f) the expenditure incurred thereon? Answer THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS (SH. TAPAN SIKADAR) (a) & ( b): There is 238974 waiting list in Gujarat Telecom Circle as on 30.6.2001. The waiting list of Jamnagar and Dahod revenue district are as under. Jamnagar 10190 Dahod 3609 (c) New connections provided in Gujarat Telecom Circle during last three years and till date district wise are. S.N. SSA RevenueDistrict covered New Tel. Connections provided during 98-99 99-00 00-01 UptoJune 01 1 Ahmedabad Ahmedabad 36627 90757 83429 7947 Gandhinagar 1888 2 Amreli Amreli 7289 8560 16146 2055 3 Bharuch Bharuch 10006 11269 16098 1244 Narmada 0 4 Bhavnagar Bhavnagar 11059 13143 20483 1300 5 Bhuj Kutch 12630 10419 15042 989 6 Godhra Punhmahal 4502 6020 13344 1090 Dahod 515 7 Jamnagar Jamnagar 9807 10651 16598 -

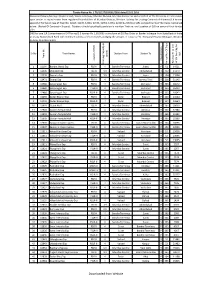

S. No. Regional Office Party/Payee Name Individual

AGRICULTURE INSURANCE COMPANY OF INDIA LTD. STATEMENT OF STALE CHEQUES As on 30.09.2017 Unclaimed amount of Policyholders related to Stale Cheques more than Rs. 1000/- TYPE OF PAYMENT- REGIONAL INDIVIDUAL/ FINANCIAL AMOUNT (IN S. NO. PARTY/PAYEE NAME ADDRESS CLAIMS/ EXCESS SCHEME SEASON OFFICE INSTITUTION RS.) COLLECTION (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (i) (j) (k) (l) (m) 1 AHMEDABAD BANK OF BARODA, GODHARA FINANCIAL INSTITUTION STATION ROAD ,GODHARA 2110.00 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2006 2 AHMEDABAD STATE BANK OF INDIA, NADIAD FINANCIAL INSTITUTION PIJ ROAD,NADIAD 1439.70 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2006 3 AHMEDABAD STATE BANK OF INDIA (SBS),JUNAGADH FINANCIAL INSTITUTION CIRCLE CHOWK,JUNAGADH 1056.00 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2007 4 AHMEDABAD UNION BANK OF INDIA, NADIAD FINANCIAL INSTITUTION TOWER,DIST.KHEDA,NADIAD 1095.50 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2007 5 AHMEDABAD BANK OF BARODA, MEHSANA FINANCIAL INSTITUTION STATION ROAD,MEHSANA 1273.80 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2008 PATNAGAR YOJANA 6 AHMEDABAD BANK OF INDIA, GANDHINAGAR FINANCIAL INSTITUTION 13641.60 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2008 BHAVAN,GHANDHINAGAR 7 AHMEDABAD ORIENTAL BANK OF COMMERCE, UNJHA FINANCIAL INSTITUTION DIST.MEHSANA,UNJA 16074.00 EXCESS COLLECTION NAIS KHARIF 2008 OTHERS 8 AHMEDABAD NAJABHAI DHARAMSIBHAI SAKARIYA INDIVIDUAL DHANDHALPUR, CHOTILA 1250.00 CLAIMS KHARIF 2009 PRODUCTS OTHERS 9 AHMEDABAD TIGABHAI MAVJIBHAI INDIVIDUAL PALIYALI, TALAJA, BHAVNAGAR 1525.00 CLAIMS KHARIF 2009 PRODUCTS OTHERS 10 AHMEDABAD REMATIBEN JEHARIYABHAI VASAVA INDIVIDUAL SAGBARA, -

Inventory of Soil Resources of Dahod District, Gujarat Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques

Inventory of Soil Resources of Dahod District, Gujarat Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques ABSTRACT 1. Survey Area Dahod district, Gujarat 2. Geographical Extent 73°15' to 74°30'- East Longitude. 20°30' to 23°30’- North Latitude. 3. Agro Climate Region Semi-Arid - Gujarat plain and hills. 4. Total area of the district 3,88,067 ha. 5. Kind of Survey Soil Resource Mapping using Remote Sensing Techniques. 6. Base map (a) IRS-ID Geo-coded Satellite Imagery (1:50,000 Scale) (b) SOI –Toposheet ( 1:50,000 scale ) 7. Scale of mapping 1:50,000 8. Period of survey Dec, 2008 9. Soil Series association mapped and their respective area. S. Mapping Mapping Soil Association Area (ha) Area % No unit symbol 1 BAn8c1 B02 Dungra-Kavachiya 1116 0.29 2 BAn8d1 B03 Kavachiya-Dungra 1057 0.27 3 BAn6c1 B04 Kavachiya-Dungra 133 0.03 4 BAn6c2 B05 Dungra-Kavachiya 5270 1.36 5 BAn6a1 B06 Kavachiya-Dungra 1913 0.49 6 BAu5a1 B07 Singalvan-Jambar 9848 2.54 7 BAu4a1 B08 Jambar-Singalvan 7998 2.06 8 BAu4d1 B09 Jambar-Singalvan 7618 1.96 9 BAv3a1 B10 Chandravan-Kadaba 9502 2.45 10 BAw2a1 B11 Sagbara-Chandeliya 7487 1.93 11 BAw2a2 B12 Chandeliya-Sagbara 3964 1.02 12 BAg4d1 B13 Kadaba-Chandeliya 473 0.12 13 BAu5a2 B14 Singalvan-Jambar 954 0.25 14 GRn8c1 G01 Dhanpur-Dungarwant 3977 1.02 15 GRn8d1 G02 Dhanpur-Dungarwant 8307 2.14 16 GRn6d1 G04 Dhanpur-Dungarwant 498 0.13 17 GRn6c1 G05 Dhanpur-Dungarwant 1614 0.42 18 GRu4c1 G06 Surkheda-Od 3002 0.77 19 GRu4d1 G07 Surkheda-Panvad 2047 0.53 20 GRu4a1 G08 Surkheda-Dhamodi 10427 2.69 21 GRv3a1 G09 Od-Bardoli 5416 1.40 22 GRw2a1 -

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (As on 20.11.2020)

List of Eklavya Model Residential Schools in India (as on 20.11.2020) Sl. Year of State District Block/ Taluka Village/ Habitation Name of the School Status No. sanction 1 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Y. Ramavaram P. Yerragonda EMRS Y Ramavaram 1998-99 Functional 2 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Kodavalur Kodavalur EMRS Kodavalur 2003-04 Functional 3 Andhra Pradesh Prakasam Dornala Dornala EMRS Dornala 2010-11 Functional 4 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Gudem Kotha Veedhi Gudem Kotha Veedhi EMRS GK Veedhi 2010-11 Functional 5 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Buchinaidu Kandriga Kanamanambedu EMRS Kandriga 2014-15 Functional 6 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Maredumilli Maredumilli EMRS Maredumilli 2014-15 Functional 7 Andhra Pradesh SPS Nellore Ozili Ojili EMRS Ozili 2014-15 Functional 8 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Meliaputti Meliaputti EMRS Meliaputti 2014-15 Functional 9 Andhra Pradesh Srikakulam Bhamini Bhamini EMRS Bhamini 2014-15 Functional 10 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Munchingi Puttu Munchingiputtu EMRS Munchigaput 2014-15 Functional 11 Andhra Pradesh Visakhapatanam Dumbriguda Dumbriguda EMRS Dumbriguda 2014-15 Functional 12 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Makkuva Panasabhadra EMRS Anasabhadra 2014-15 Functional 13 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Kurupam Kurupam EMRS Kurupam 2014-15 Functional 14 Andhra Pradesh Vizianagaram Pachipenta Guruvinaidupeta EMRS Kotikapenta 2014-15 Functional 15 Andhra Pradesh West Godavari Buttayagudem Buttayagudem EMRS Buttayagudem 2018-19 Functional 16 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Chintur Kunduru EMRS Chintoor 2018-19 Functional -

Profile of Lecturer

Profile of Lecturer Affix Passport sized a) Name (In block letters):MARU RAJESHKUMAR NAGJIBHAI Photograph b) Address (Residential): 1268 SHIVAM SOCIETY, SECTOR-27, GANDHINAGAR. c) Contact Detail: Ph. No. (M):9427604539 E-mail ID: [email protected] d) Designation: ASSISTANT PROFESSOR e) Department: Biology f) Date of Birth: 23-04-1970 g) Area of Specialization: C. Academic Qualifications Exam University/Agency Subject Year Class/ Passed Grade B. Sc. Gujarat university Botany 1995 Second M. Sc. Gujarat university Botany 1998 Second M. Phil. Gujarat university Botany - 2002 FirstDist Ph. D. J J T University,Junjnu Rajsthan Ethnobotany 2014 - GPSC GPSC - 2003 (GES, Class-II) CCC+ CCC+ - - Pass Any Others Gujarat university SCIENCE 1996 FirstDist B.Ed 1 D. Research Experience & Training Research Title of work/Theses University Stage where the work was carried out M. Phil A STUDY ON GROWTH RESPONSE OF MUSTARD SUBJECTED TO Gujarat DIRECT,PHASIC,PRETREATMENT AND FOLIAR APPLICATIONS OF university HEAVY METALS Ph.D. AN ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDY OF JHALOD continue J J T university,Junj TALUKA,DAHOD DISTRICT,GUJARAT,INDIA. nu Rajsthan - - - Post-Doctoral - - Research . R.N. Maru, And Dr. R.S. Patel, Code : Bp-6 - Publications Ethno-Medicinal Plants Used To Cure Different (give a list Diseases By Tribals Of Jhalod Taluka Of Dhahod separately) District, Gujarat, India Page No. 26 National Symposium, Organized By Department Of Botany, Ussc, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, 13-15 October, 2011 . Maru R.N. And Patel R.S., Certain Plants Used In House Hold Instruments And Agriculture Impliments By The Tribals Of Jhalod Taluka, Dahod District Of Gujarat, India Page No. -

New Police Station.Pdf

Police Station New Court Wise Police Station District Court Dahod Name of the Police Station Court ACB Police Station Principal District Court, Dahod Dahod Town Police Station – Dahod District Dahod Rural Police Station – Dahod District Dahod Mahila Police Station – Dahod District katwara Police Station – Dahod District Devgadh BariaPolice Station – Dahod District Jhalod Police Station – Dahod District Limbdi Police Station – Dahod District Additional District Court, Dahod Sanjeli Police Station – Dahod District (Spl. Court POSCO) Dhanpur Police Station – Dahod District Fatepura Police Station – Dahod District Sukhsar Police Station – Dahod District Limkheda Police Station – Dahod District Randhikpur Police Station – Dahod District Garbada Police Station – Dahod District Jesawada Police Station – Dahod District Civil Court, Dahod Name of the Police Station Court Dahod Town Police Station – Dahod District Dahod Rural Police Station – Dahod District Chief Judicial Magistrate, Dahod Dahod Mahila Police Station – Dahod District katwara Police Station – Dahod District Dahod Town Police Station – Dahod District Dahod Rural Police Station – Dahod District Dahod Mahila Police Station – Dahod District katwara Police Station – Dahod District Devgadh BariaPolice Station – Dahod District Jhalod Police Station – Dahod District Limbdi Police Station – Dahod District Sanjeli Police Station – Dahod District Juvenile Justices Board Dhanpur Police Station – Dahod District Fatepura Police Station – Dahod District Sukhsar Police Station – Dahod District Limkheda Police Station – Dahod District Randhikpur Police Station – Dahod District Garbada Police Station – Dahod District Jesawada Police Station – Dahod District Taluka Court, Devgadh Baria Name of the Police Station Court Devgadh BariaPolice Station – Dahod District Principal Civil & J. M. F. C. Court, Devgadh Baria Taluka Court, Jhalod Name of the Police Station Court Jhalod Police Station – Dahod District Principal Civil & J. -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

District Fact Sheet Dahod Gujarat

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Family Health Survey - 5 2019-20 District Fact Sheet Dahod Gujarat International Institute for Population Sciences (Deemed University) 1 Introduction The National Family Health Survey 2019-20 (NFHS-5), the fifth in the NFHS series, provides information on population, health, and nutrition for India and each state/union territory (UT). Like NFHS-4, NFHS-5 also provides district-level estimates for many important indicators. The contents of NFHS-5 are similar to NFHS-4 to allow comparisons over time. However, NFHS-5 includes some new topics, such as preschool education, disability, access to a toilet facility, death registration, bathing practices during menstruation, and methods and reasons for abortion. The scope of clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical testing (CAB) has also been expanded to include measurement of waist and hip circumferences, and the age range for the measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose has been expanded. However, HIV testing has been dropped. The NFHS-5 sample has been designed to provide national, state/union territory (UT), and district level estimates of various indicators covered in the survey. However, estimates of indicators of sexual behaviour; husband’s background and woman’s work; HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour; and domestic violence are available only at the state/union territory (UT) and national level. As in the earlier rounds, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, designated the International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, as the nodal agency to conduct NFHS-5. The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide high-quality data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area. -

Downloaded from Website Sr.No Train Name Station from Station to SLR

Tender Notice No. C 78/1/117/SLR/01/2016 dated 22.01.2016 Divisional Railway Manager (Commercial), Western Railway, Mumbai Division, Mumbai Central for and on behalf of The President of India invites open tender in sealed covers from registered leaseholders of Mumbai Division, Western Railway for Leasing Contract of 4 tonnes/3.9 tonnes space (3.9 Tonnes in case of Train No. 12009, 12239, 12931, 12933, 12951, 12953, 22209 & 22903) in SLRs Compartments of the trains mentioned below. (Period Of Contract = 3 years) . Tenderer should specifically and clearly mention Train no. and Location of SLR on cover of their tender offer. EMD for one SLR Compartment of 04 Tonnes/3.9 tonnes=Rs. 1,00,000/- in the form of DD/Pay Order or Banker's cheque from State Bank of India or of any Nationalised Bank with minimum validity of three months pledging the amount in favour of "Sr. Divisional Finance Manager, Western Railway, Mumbai Central. Sr.No Train Name Station From Station To SLR. tonnes Train No. Classification Location Of SLR of 2% Dev.Chg for Reserve Price incl. Annual No. Of Trips Carrying Capacity in 1 11104 Bandra Jhansi Exp FSLR-I 4 Bandra Terminus Jhansi P 52 14321 2 12009 Shatabdi Exp FSLR-I 3.9 Mumbai Central Ahmedabad R 312 11279 3 12239 Duranto Exp FSLR-I 3.9 Mumbai Central Jaipur R 104 23398 4 12471 Swaraj Exp FSLR-I 4 Bandra Terminus Jammu Tawi R 208 31140 5 12480 Suryanagari Exp FSLR-I 4 Bandra Terminus Jodhapur R 365 16042 6 12480 Suryanagari Exp FSLR-II 4 Bandra Terminus Jodhapur R 365 16042 7 12480 Suryanagari Exp RSLR-III 4 Bandra Terminus Jodhapur R 365 16042 8 12490 Dadar Bikaner Exp. -

NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY of INDIA G-5&6, SECTOR-10, DWARKA, NEW DELHI-110075 Notice Inviting Bid Bid/ Package No. NHAI/BM

NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA G-5&6, SECTOR-10, DWARKA, NEW DELHI-110075 Notice Inviting Bid Bid/ Package no. NHAI/BM/ Delhi-Vadodara/2018/Pkg27 Dated 21.02.2020 RFP for Construction of Eight Lane access-controlled expressway starting after the end of Bridge over Hadaf River near Hathiyavan village in Dahod district and ending at junction with SH-152 near Matariya Vadi village in Panchmahal district (Ch.729+700 to 756+052) section of Delhi – Vadodara Greenfield Alignment (NH-148N) on EPC Mode under Bharatmala Pariyojana in the State of Gujarat. The Ministry of Road Transport & Highways through National Highways Authority of India is engaged in the development of National Highways and as part of this endeavour, it has been decided to undertake Construction of Eight Lane access-controlled expressway starting after the end of Bridge over Hadaf River near Hathiyavan village in Dahod district and ending at junction with SH-152 near Matariya Vadi village in Panchmahal district (Ch.729+700 to 756+052) section of Delhi – Vadodara Greenfield Alignment (NH-148N) under Bharatmala Pariyojana in the State of Gujarat through an Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) Contract. The National Highways Authority of India represented by its Chairman now invites bids from eligible contractors for the following project: State NH ICB Name of work Estimated Completion Maintenance No. No. cost period period Gujarat 148-N NHAI/ Construction of Eight Rs. 874.04 2 Years 10 Years BM/ Lane access-controlled Crore Delhi- expressway starting after Vadoda the end of Bridge over ra/2018 Hadaf River near /Pkg27 Hathiyavan village in Dahod district and ending at junction with SH-152 near Matariya Vadi village in Panchmahal district (Ch.729+700 to 756+052) section of Delhi – Vadodara Greenfield Alignment (NH-148N) on EPC Mode under Bharatmala Pariyojana in the State of Gujarat. -

Available Phosphorus in Soil of Halol, Kalol and Morva Hadaf Taluka Territory of Panchmahal District by Soil Health Card Study Project

Available online a twww.scholarsresearchlibrary.com Scholars Research Library Archives of Applied Science Research, 2016, 8 (8):8-13 (http://scholarsresearchlibrary.com/archive.html) ISSN 0975-508X CODEN (USA) AASRC9 Available phosphorus in soil of Halol, Kalol and Morva Hadaf taluka Territory of Panchmahal District by soil health card study project Dilip H. Pate 1 and M. M. Lakdawala Chemistry Department, S P T Arts and Science College, Godhra, Gujarat, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Under Gujarat Government “Soil Health Card Project” this results are reproduced, This physico-chemical study of soil covers various parameters like pH, conductivity, Total Organic Carbon, Available Nitrogen (N), Available Phosphorus (P 2O5) and Available Potassium (K 2O). This study lead us to the conclusion about the nutrient’s quantity and quality of soil of Halol, Kalol and Morva hadaf Taluka, District- Panchmahal, Gujarat. Results show that average all the villages of all three talukas have medium and very few have high Phosphorus content. The fertility index for phosphorus for all three talukas is average 2.00. This information will help farmer to know the status of their farms, requirements of nutrients addition for soil for the next crop session, that means which fertilizer to be added. Key words: Quality of soil, fertility index, Kalol, Gujarat _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Soil composition is: