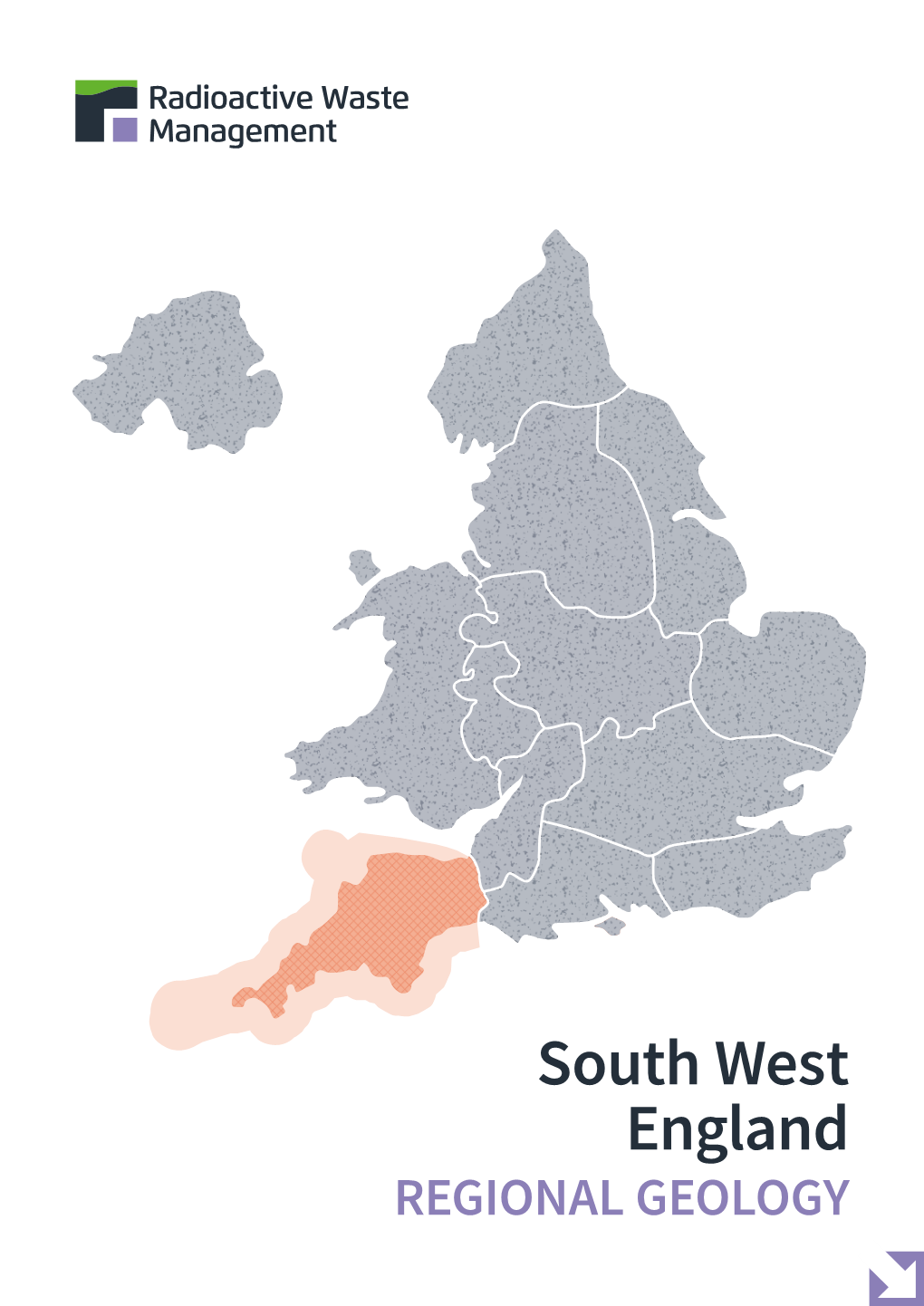

RWM South West England Regional Geology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Developments in Uk Mining Projects

CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN UK MINING PROJECTS C P Broadbent1) and C A Blackmore1) 1)Wardell Armstrong International Ltd, 46 Chancery Lane, London WC2A 1JE, UK 1 Introduction In October 2017 The Mining Technology Division (MTD) of the IOM3 organised a highly successful conference “Current Developments in the UK Mining Industry”. The aims and objectives of the conference was to define the then current state of the UK Mining Industry1. This conference was a great success and, with the exception of a presentation on Wolf Minerals Ltd, Hemerdon Project, gave the definitive status of most major UK Mining Projects. This paper provides an update of many of these projects. Although the last UK deep pit coal mine, Kellingley Colliery, North Yorkshire closed in December 20152 and was capped off in March 2016. The UK still has large reserves of available fossil fuels and many types of industrial minerals and metals are found in the diverse geology of the UK. Presently there are a number of major initiatives active making 2018, despite events at Hemerdon, one of the most active years in recent times for “new” UK mining ventures. The locations of the projects covered in this paper are shown in Figure 1. 1) 1 Sirius Minerals Plc 2 British Fluorspar Limited 3 West Cumbria Mining 4 Cornish Lithium Limited 5 South Crofty – Strongbow Exploration 8 6 Cornwall Resources Limited – Redmoor Project 7 Dalradian Gold Limited – Curraghinalt Project 8 Scotgold Resources – Cononish Mine 7 3 1 9 Anglesea Mining Plc – Parys Mountain 10 Wolf Minerals Limited - Drakelands Mine 2 Figure 1: Location of the projects c 9 o vered in this paper this paper 10 6 4 5 1 Current Developments – The UK Mining Industry – Presentations at MTD Conference, London 4-5 October 2017 2 Dodgson, L. -

Cetaceans of South-West England

CETACEANS OF SOUTH-WEST ENGLAND This region encompasses the Severn Estuary, Bristol Channel and the English Channel east to Seaton on the South Devon/Dorset border. The waters of the Western Approaches of the English Channel are richer in cetaceans than any other part of southern Britain. However, the diversity and abundance declines as one goes eastwards in the English Channel and towards the Severn Estuary. Seventeen species of cetacean have been recorded in the South-west Approaches since 1980; nine of these species (32% of the 28 UK species) are present throughout the year or recorded annually as seasonal visitors. Thirteen species have been recorded along the Channel coast or in nearshore waters (within 60 km of the coast) of South-west England. Seven of these species (25% of the 28 UK species) are present throughout the year or are recorded annually. Good locations for nearshore cetacean sightings are prominent headlands and bays. Since 1990, bottlenose dolphins have been reported regularly nearshore, the majority of sightings coming from Penzance Bay, around the Land’s End Peninsula, and St. Ives Bay in Cornwall, although several locations along both north and south coasts of Devon are good for bottlenose dolphin. Cetaceans can also been seen in offshore waters. The main species that have been recorded include short- beaked common dolphins and long-finned pilot whales. Small numbers of harbour porpoises occur annually particularly between October and March off the Cornish & Devon coasts. CETACEAN SPECIES REGULARLY SIGHTED IN THE REGION Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus Rarer visitors to offshore waters, fin whales have been sighted mainly between June and December along the continental shelf edge at depths of 500-3000m. -

Quaternary of South-West England Titles in the Series 1

Quaternary of South-West England Titles in the series 1. An Introduction to the Geological Conservation Review N.V. Ellis (ed.), D.Q. Bowen, S. Campbell,J.L. Knill, A.P. McKirdy, C.D. Prosser, M.A. Vincent and R.C.L. Wilson 2. Quaternary ofWales S. Campbeiland D.Q. Bowen 3. Caledonian Structures in Britain South of the Midland Valley Edited by J.E. Treagus 4. British Tertiary Voleanie Proviflee C.H. Emeleus and M.C. Gyopari 5. Igneous Rocks of Soutb-west England P.A. Floyd, C.S. Exley and M.T. Styles 6. Quaternary of Scotland Edited by J.E. Gordon and D.G. Sutherland 7. Quaternary of the Thames D.R. Bridgland 8. Marine Permian of England D.B. Smith 9. Palaeozoic Palaeobotany of Great Britain C.]. Cleal and B.A. Thomas 10. Fossil Reptiles of Great Britain M.]. Benton and P.S. Spencer 11. British Upper Carboniferous Stratigraphy C.J. Cleal and B.A. Thomas 12. Karst and Caves of Great Britain A.C. Waltham, M.J. Simms, A.R. Farrant and H.S. Goidie 13. Fluvial Geomorphology of Great Britain Edited by K.}. Gregory 14. Quaternary of South-West England S. Campbell, C.O. Hunt, J.D. Scourse, D.H. Keen and N. Stephens Quaternary of South-West England S. Campbell Countryside Council for Wales, Bangor C.O. Hunt Huddersfield University J.D. Scourse School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor D.H. Keen Coventry University and N. Stephens Emsworth, Hampshire. GCR Editors: C.P. Green and B.J. Williams JOINT~ NATURE~ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE SPRINGER-SCIENCE+BUSINESS MEDIA, B.V. -

Consultation Draft of the North Devon Coast Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019 - 2024

Consultation Draft of the North Devon Coast Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2019 - 2024 Contents • A 20 Year Vision 2.4 Environmental Quality and Climate Change • Ministerial Foreword • AONB Partnership Chairman Foreword 3. People and Prosperity • Map of the AONB 3.1. Planning, Development and Infrastructure • Summary of Objectives and Policies 3.2. Farming and Land Management • Statement of Significance and Special Qualities 3.3. Sustainable Rural and Visitor Economy 3.4. Access, Health and Wellbeing 1. Context 1.1. Purpose of the AONB Designation 4. Communications and Management 1.2. State of the AONB 4.1. Community Action, Learning and Understanding 1.3. Strategic and Policy Context 4.2. Management and Monitoring 1.4. The North Devon UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve 1.5. Setting and Boundary Review 5. Appendices 5.1 Glossary 2. Place 5.2 References 2.1 Landscape and Seascape 5.3 Abbreviations 2.2 Biodiversity and Geodiversity 2.3 Historic Environment and Culture North Devon Coast AONB Consultation Draft Management Plan 2018 1 A 20 Year Vision “The North Devon Coast AONB will remain as one of England’s finest landscapes and seascapes, protected, inspiring and valued by all. Its natural and cultural heritage will sustain those who live in, work in or visit the area. It will be valued by residents and visitors alike who will have increased understanding of what makes the area unique and will be addressing the challenges of keeping it special to secure its long-term future.” Ministerial Foreword AONB Partnership Chairman -

Having Your Head & Neck Surgery in Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital

Your operation will be performed at We request that visitors respect other Discharge Exeter Hospital (Wonford) by your patients on the ward and keep noise On the morning of your discharge, Torbay Surgeon M………………… levels to a minimum. following breakfast, you may be asked During your recovery you will be to dress and sit in the dayroom. This cared for by the Exeter Team. Once Well behaved and supervised children enables us to prepare the bed for the you are fit to go home, your care are welcome. We also ask that visitors next patient. Please allow up to 4 will revert back to the Team at sit on the chairs provided and not on hours for your medication to be Torbay. the beds. dispensed from the pharmacy. Otter ward Please always use the hand gel A follow up appointment to see your provided when arriving and leaving the Torbay surgeon will be arranged by Otter ward is situated on Level 2 Area ward. the Torbay team and will be sent to J. It is a 24 bedded ward which your home address after you have specialises in Ear, Nose & Throat, been discharged from Otter ward. Oral & Maxillofacial and Ophthalmic Ward meal & snack times Surgery You will be admitted to Knapp Ward Breakfast is served at 8am. Level 2 in the Orthopaedic Centre on Wednesday morning for operation on Morning drinks and snacks at 10 am. the same day and transferred to Otter Ward after your operation. Lunch is served at 12 pm. If you feel this is not possible, please Afternoon drinks and snacks 3 pm. -

West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme

Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective 2007 – 2013 West Midlands European Regional Development Fund Operational Programme Version 3 July 2012 CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 – 5 2a SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS - ORIGINAL 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 6 – 14 2.2 Employment 15 – 19 2.3 Competition 20 – 27 2.4 Enterprise 28 – 32 2.5 Innovation 33 – 37 2.6 Investment 38 – 42 2.7 Skills 43 – 47 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 48 – 50 2.9 Rural 51 – 54 2.10 Urban 55 – 58 2.11 Lessons Learnt 59 – 64 2.12 SWOT Analysis 65 – 70 2b SOCIO-ECONOMIC ANALYSIS – UPDATED 2010 2.1 Summary of Eligible Area - Strengths and Challenges 71 – 83 2.2 Employment 83 – 87 2.3 Competition 88 – 95 2.4 Enterprise 96 – 100 2.5 Innovation 101 – 105 2.6 Investment 106 – 111 2.7 Skills 112 – 119 2.8 Environment and Attractiveness 120 – 122 2.9 Rural 123 – 126 2.10 Urban 127 – 130 2.11 Lessons Learnt 131 – 136 2.12 SWOT Analysis 137 - 142 3 STRATEGY 3.1 Challenges 143 - 145 3.2 Policy Context 145 - 149 3.3 Priorities for Action 150 - 164 3.4 Process for Chosen Strategy 165 3.5 Alignment with the Main Strategies of the West 165 - 166 Midlands 3.6 Development of the West Midlands Economic 166 Strategy 3.7 Strategic Environmental Assessment 166 - 167 3.8 Lisbon Earmarking 167 3.9 Lisbon Agenda and the Lisbon National Reform 167 Programme 3.10 Partnership Involvement 167 3.11 Additionality 167 - 168 4 PRIORITY AXES Priority 1 – Promoting Innovation and Research and Development 4.1 Rationale and Objective 169 - 170 4.2 Description of Activities -

Unravelling Devon Involvement in Slave-Ownership Lucy

Unravelling Devon involvement in Slave-Ownership Lucy MacKeith ‘The early history of the United States of America owes more to Devon than to any other English county.’ Charles Owen (ed.), The Devon-American Story (1980) My task this afternoon is to unravel Devon’s involvement in slave-ownership. I have found the task overwhelming because of constantly finding new information – there are leads to follow down little branches of family trees, there are Devon’s country houses, a wealth of documents, and – of course – the internet. So this is a VERY brief introduction to unravelling Devon’s involvement with slave- ownership – much has been left out. Let’s start with Elias Ball. His story is in Slaves in the Family, written by descendant Edward Ball and published in 1998. Elias Ball by Jeremiah Theus (1716-1774). ‘Elias Ball, ...was born in 1676 in a tiny hamlet in western England called Stokeinteignhead. He inherited a plantation in Carolina at the end of the seventeenth century ...His life shows how one family entered the slave business in the birth hours of America. It is a tale composed equally of chance, choice and blood.’ The book has many Devon links – an enslaved woman called Jenny Buller reminds us of Redvers Buller’s family, a hill in one of the Ball plantations called ‘Hallidon Hill’ reminds us of Haldon Hill just outside Exeter; two family members return to England, one after the American War of Independence. This was Colonel Wambaw Elias Ball who had been involved in trading in enslaved Africans in Carolina. He was paid £12,700 sterling from the British Treasury and a lifetime pension in compensation for the slaves he had lost in the war of independence. -

Annual Report 2010-2011

Incorporating community services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon AAnnualnnual RReporteport 2010 - 2011 Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust 2 CContentsontents Introduction . 3 Trust background . 4 Our area . 7 Our community . 7 Transforming Community Services (TCS) . 7 Our values . 7 Our vision . 7 Patient experience . 9 What you thought in 2010-11 . 10 Telling us what you think . .12 Investment in services for patients . 13 Keeping patients informed . 15 Outpatient reminder scheme launched in April 2011 . 15 Involving patients and the public in improving services . 16 Patient Safety . .17 Safe care in a safe environment . .18 Doing the rounds . 18 Preventing infections . 18 Norovirus . 18 A learning culture . 19 High ratings from staff . .20 Performance . 21 Value for money . 22 Accountability . 22 Keeping waiting times down . 22 Meeting the latest standards . 22 Customer relations . 23 Effective training and induction . .24 Dealing with violence and aggression . 24 Operating and Financial Review . 25 Statement of Internal Control . 39 Remuneration report . .46 Head of Intenal Audit opinion . 50 Accounts . 56 Annual Report 2010 - 11 3 IIntroductionntroduction Running a complex organisation is about ensuring that standards are maintained and improved at the everyday level while taking the right decisions for the longer term. The key in both hospital and community-based services is to safeguard the quality of care and treatment for patients. That underpins everything we do. And as this report shows, there were some real advances last year. For example, our new service for people with wet, age-related macular degeneration (WAMD) – a common cause of blindness – was recognised as among the best in the South West. -

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014

West of Exeter Route Resilience Study Summer 2014 Photo: Colin J Marsden Contents Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 02 1. Executive summary 03 2. Introduction 06 3. Remit 07 4. Background 09 5. Threats 11 6. Options 15 7. Financial and economic appraisal 29 8. Summary 34 9. Next steps 37 Appendices A. Historical 39 B. Measures to strengthen the existing railway 42 1. Executive summary Summer 2014 Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study 03 a. The challenge the future. A successful option must also off er value for money. The following options have been identifi ed: Diffi cult terrain inland between Exeter and Newton Abbot led Isambard Kingdom Brunel to adopt a coastal route for the South • Option 1 - The base case of continuing the current maintenance Devon Railway. The legacy is an iconic stretch of railway dependent regime on the existing route. upon a succession of vulnerable engineering structures located in Option 2 - Further strengthening the existing railway. An early an extremely challenging environment. • estimated cost of between £398 million and £659 million would Since opening in 1846 the seawall has often been damaged by be spread over four Control Periods with a series of trigger and marine erosion and overtopping, the coastal track fl ooded, and the hold points to refl ect funding availability, spend profi le and line obstructed by cliff collapses. Without an alternative route, achieved level of resilience. damage to the railway results in suspension of passenger and Option 3 (Alternative Route A)- The former London & South freight train services to the South West peninsula. -

University Public Transport Map and Guide 2018

Fancy a trip to Dartmouth Plymouth Sidmouth Barnstaple Sampford Peverell Uffculme Why not the beach? The historic port of Dartmouth Why not visit the historic Take a trip to the seaside at Take a trip to North Devon’s Main Bus has a picturesque setting, maritime City of Plymouth. the historic Regency town main town, which claims to be There are lots of possibilities near Halberton Willand Services from being built on a steep wooded As well as a wide selection of of Sidmouth, located on the the oldest borough in England, try a day Exeter, and all are easy to get to valley overlooking the River shops including the renowned Jurassic Coast. Take a stroll having been granted its charter Cullompton by public transport: Tiverton Exeter Dart. The Pilgrim Fathers sailed Drakes Circus shopping centre, along the Esplanade, explore in 930. There’s a wide variety Copplestone out by bus? Bickleigh Exmouth – Trains run every from Dartmouth in 1620 and you can walk up to the Hoe the town or stroll around the of shops, while the traditional Bradninch There are lots of great places to half hour and Service 57 bus many historic buildings from for a great view over Plymouth Connaught Gardens. Pannier Market is well worth Crediton runs from Exeter Bus station to Broadclyst visit in Devon, so why not take this period remain, including Sound, visit the historic a visit. Ottery St Mary Exmouth, Monday to Saturday Dartmouth Castle, Agincourt Barbican, or take a trip to view Exeter a trip on the bus and enjoy the Airport every 15 mins, (daytime) and Newton St Cyres House and the Cherub Pub, the ships in Devonport. -

SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Frequently Asked Questions

SOUTH WEST ENGLAND Frequently Asked Questions Product Information & Key Contacts 2016 Frequently Asked Questions Bath Bath Visitor Information Centre Abbey Chambers Abbey Churchyard Bath BA1 1LY Key contact: Katie Sandercock Telephone: 01225 322 448 Email: [email protected] Website: www.visitbath.co.uk Lead product Nourished by natural hot springs, Bath is a UNESCO World Heritage city with stunning architecture, great shopping and iconic attractions. Rich in Roman and Georgian heritage, the city has been attracting visitors with its obvious charms for well over 2000 years and is now the leading Spa destination of the UK. Some of the highlights of the city include: The Roman Baths - constructed around 70 AD as a grand bathing and socialising complex. It is now one of the best preserved Roman remains in the world. Thermae Bath Spa – bathe in Bath’s natural thermal waters. Highlights include the indoor Minerva Bath, steam rooms, and an open-air rooftop pool with amazing views over the city. A fantastic range of treatments including massage, facials and water treatments can be booked in advance. Gainsborough Bath Spa Hotel – Britain’s first natural thermal spa hotel. Opened in July 2015. A five-star luxury hotel located in the centre of Bath. Facilities include 99 bedrooms (some with access to Bath’s spring water in their own bathrooms), The Spa Village Bath and Johan Lafer’s ‘Dining Without Borders’ restaurant. Bath Abbey - Magnificent stained glass windows, columns of honey-gold stone and some of the finest fan vaulting in the world, create an extraordinary experience of light and space. -

Agricultural Facts: England Regional Profiles

Defra statistics: Agricultural facts – South West (commercial holdings at June 2019 (unless stated) The South West region comprises Cornwall & Isles of Scilly, Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Bristol / Bath area. Dartmoor and Exmoor National Parks are within the region. For the South West region: Total Income from Farming increased by 46% between 2015 and 2019 to £644 million. The biggest contributors to the value of the output (£4.1 billion), which were milk (£1,105 million), plants and flowers (£545 million), cattle for meat (£357 million) and poultry meat (£304 million), together accounting for 57%. (Sourced from Defra Aggregate agricultural accounts) In the South West the average farm size in 2019 was 68 hectares. This is smaller than the English average of 87 hectares. Predominant farm types in the South West region in 2019 were Grazing Livestock farms which accounted for 36% of farmed area in the region, Cereals farms and Dairy farms which covered an additional 20% and 18% of farmed area each. Land Labour South West England South West England Total farmed area (thousand 1,789 9,206 Total Labour(a) hectares People: 64,610 306,374 Average farm size (hectares) 68 87 Per farm(b) 2.5 2.9 % of farmed area that is: Regular workers Rented (for at least 1 year) 31% 33% People: 13,406 68,962 Arable area(a) 41% 52% Per farm(b) 0.5 0.6 Permanent pasture 48% 36% Casual workers Severely Disadvantaged Area 7% 13% People: 5,455 45,843 (a) Includes arable crops, uncropped arable land and Per farm(b) 0.2 0.4 temporary grass.