MASTER THESIS Abstract the Title of the Study Is “The Use of Advergames in Creating Online Consumer Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEGO Ninjago 500 Stickers Free

FREE LEGO NINJAGO 500 STICKERS PDF EGMONT UK LTD | 64 pages | 08 Oct 2015 | Egmont UK Ltd | 9781405279024 | English | London, United Kingdom lego ninjago stickers - 99 results | Here at Walmart. Your email address will never be sold or distributed to a third party for any reason. Sorry, but we can't respond to individual comments. If you need immediate assistance, please contact Customer Care. Your feedback helps us make Walmart shopping better for millions of LEGO Ninjago 500 Stickers. Recent searches Clear All. Enter Location. Update location. Learn more. Report incorrect product information. Egmont UK Ltd. Out of stock. Delivery not available. Pickup not available. Add to list. Add to registry. Are you ready for an adventure in the world of Ninjago? This exciting activity book is full of puzzles to solve, pictures to colour in and over reusable stickers! Enjoy completing the activities and pasting the stickers as you help the Ninjago in their missions. Then when you've finished, peel off the stickers and past them again wherever you want! Young masters of Spinjitzu will love the Lego registered Ninjago activity books packed with activities, stickers, and awesome facts LEGO Ninjago 500 Stickers their favourite Ninja. There are hours of fun to be had for kids aged 5 and up. Do you own all the Lego registered Ninjago titles? About This Item. We aim to show you accurate product information. Manufacturers, suppliers and others provide what you see here, and we have not verified it. See our disclaimer. Young masters of Spinjitzu will love the Lego Ninjago activity books packed with activities, stickers, and awesome facts about their favourite LEGO Ninjago 500 Stickers. -

2006 FIRST Annual Report

annual report For Inspiration & Recognition of Science & Technology 2006 F I R Dean Kamen, FIRST Founder John Abele, FIRST Chairman President, DEKA Research & Founder Chairman, Retired, Development Corporation Boston Scientific Corporation S Recently, we’ve noticed a shift in the national conversation about our People are beginning to take the science problem personally. society’s lack of support for science and technology. Part of the shift is in the amount of discussion — there is certainly an increase in media This shift is a strong signal for renewed commitment to the FIRST T coverage. There has also been a shift in the intensity of the vision. In the 17 years since FIRST was founded, nothing has been more conversation — there is clearly a heightened sense of urgency in the essential to our success than personal connection. The clearest example calls for solutions. Both these are positive developments. More is the personal commitment of you, our teams, mentors, teachers, parents, awareness and urgency around the “science problem” are central to sponsors, and volunteers. For you, this has been personal all along. As the FIRST vision, after all. However, we believe there is another shift more people make a personal connection, we will gain more energy, happening and it has enormous potential for FIRST. create more impact, and deliver more success in changing the way our culture views science and technology. If you listen closely, you can hear a shift in the nature of the conversation. People are not just talking about a science problem and how it affects This year’s Annual Report echoes the idea of personal connections and P02: FIRST Robotics Competition someone else; they are talking about a science problem that affects personal commitment. -

Legoland® California Resort Announces Reopening April 1!

Media Contacts: Jake Gonzales /760-429-3288 [email protected] AWESOME IS BACK! LEGOLAND® CALIFORNIA RESORT ANNOUNCES REOPENING APRIL 1! Park Preview Days April 1-12 Includes access to select rides and attractions Resort officially reopens April 15 to include SEA LIFE® aquarium and LEGO® CHIMA™ Water Park Priority access to hotel guests, pass holders and existing ticket holders to be first Park guests in April With limited capacities, guests are required to book online in advance Resort is implementing safety guidelines LINK TO IMAGES: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/nMvjw0kEAr LINK TO BROLL: https://spaces.hightail.com/space/cNda6CmOIX CARLSBAD, Calif. (March 19, 2021) – LEGOLAND® California Resort is excited to offer Park Preview Days with access to select rides and attractions beginning April 1, 2021, under California’s reopening health and safety guidelines with official reopening on April 15, 2021. After closing its gates one year ago, the theme park built for kids is offering priority access to Hotel guests, pass holders and existing ticket holders impacted by COVID- 19 Park closure, for the month of April. Park Preview Days offers access to select rides including Driving School, LEGO® TECHNIC™ Coaster, Fairy Tale Brook and Coastersaurus. Kids and families can also enjoy socially distant character meet and greets, live entertainment, a wide variety of food options and Miniland U.S.A. The Resort officially reopens April 15, offering access to SEA LIFE® aquarium and LEGO® CHIMA™ Water Park. Guests will once again be immersed into the creative world of LEGO® and some of the Park’s more than 60 rides, shows and attractions. -

Field Trip Welcome Packet

WELCOME PACKET Thank you for choosing LEGOLAND® Florida Resort for your field trip experience! We are excited to welcome you and your students to the park for a brick-tastic time. Please review the information below for helpful hints to make your experience an easy, safe and memorable one. BEFORE YOUR VISIT CHANGES TO YOUR RESERVATION Should you need to make any modifications to your booking (update numbers, make payments, cancel your reservation, etc.), please email [email protected] and one of our Model Citizens (employees) will be in touch. All changes to your reservation, including number of students and chaperones, must be submitted ten (10) business days prior to your visit. Should you need immediate assistance, please give us a call at 1-855-753-8888. EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE GUIDES & ACTIVITY GUIDE You may download our Educational Resource Guides and the Builders of Tomorrow Activity Guide to include in pre-visit curriculum. Please visit our School Group Programs website to download these resources. FLORIDA TEACHER PASS Did you know that we offer a FREE Florida Teacher Pass for all certified teachers in Florida who teach grades PreK- 12? The Florida Teacher Pass provides unlimited admission and access to select theme park events at LEGOLAND® Florida Theme Park, as well as unlimited admission to Madame Tussauds Orlando and SEA LIFE Orlando. Upgrade your pass to include the LEGOLAND Water Park for just $49.99 + tax! Make sure you pick up your Teacher Pass prior to visiting with your field trip so that you can use your pass when you come back with your class. -

Awesome New Additions to the Legoland® Windsor Resort in 2019

AWESOME NEW ADDITIONS TO THE LEGOLAND® WINDSOR RESORT IN 2019 • Everything is Awesome as LEGOLAND Opens “The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience • Brand New The Haunted House Monster Party Ride Launching in April 2019 • LEGO® City comes to life in a new 4D movie - LEGO® City 4D – Officer in Pursuit 2019 will see exciting new additions to the LEGOLAND® Windsor Resort when it reopens for the new season. From March 2019, LEGO® fans can discover The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience, April will see the opening of a spooktacular new ride; The Haunted House Monster Party and in May, a families will see LEGO City come to life in a new 4D movie; LEGO® City 4D - Officer in Pursuit! The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience In The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience, guests can experience movie magic and explore an actual LEGO® set as seen in “The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2”. Returning heroes Emmet, Wyldstyle, and their LEGO co-stars can be spotted in their hometown of Apocalypseburg recreated in miniature LEGO scale. Families will be amazed by the details that go into making this 3D animated blockbuster movie. The LEGO® MOVIE™ 2 Experience is created out of 62,254 LEGO bricks, featuring 628 types of LEGO elements, utilizing 31 different colours. The new attraction offers guests a up-close look at Apocalypseburg and movie fans can stand in the same place as characters from the film and imagine being in the action. LEGOLAND Model Makers have been reconstructing a piece of the set from the new movie for five months, working with Warner Bros. -

5 a 9 Años 10 a 14 Años

5 a 9 años 11 10 a 14 años DESAFÍO DE SANGRE Y ARENA KARUNA RIAZI Arte de tapa provi- Un trío de amigos se encuentra atrapado dentro de un juego de mesa mecánico. Ellos deben desmantelar el juego para sorio poder salvarse y no morir atrapados dentro. Esta original novela debut está llena de acción y combina los mundos del steampunk, las Mil y una noches y Jumanji. Nada puede prepararte para El Desafío… Al principio no parecía exactamente peligroso. Cuando Farah, una niña de 12 años de origen bengalí, puso sus ojos en el anticuado juego de mesa, pensó que más bien se veía... elegante. Está hecho de madera, con relieves exquisitos —un palacio con domos y torrecillas, ventanas con vitrales que proyectan sombras irreales, una enorme araña— y en el centro de su caja, en amplias letras, está escrito: El Desafío de Sangre y Arena. El Desafío es más que un juego. Está hecho con la más antigua, y la más peligrosa magia. Dentro suyo habitan mundos dentro de mundos. Y toma a los jugadores como sus prisioneros. Páginas: HORIZONTE SCOTT WESTERFIELD Arte de tapa El primer tomo de una serie de 7 libros desarrollados por provisorio Scholastic. La serie es multi-autor y multi-plataforma, con un componente digital importante (juegos para móviles, foros y chats desarrollados en torno a la serie). Cuando un avión realiza un aterrizaje forzoso en el casco polar ártico, arctic, ocho jóvenes sobrevivientes salen al exterior esperando ver nada más que hielo y nieve. En lugar de eso, se hallan perdidos en una extraña jungla sin manera de llegar a casa y con pocas esperanzas de ser rescatados. -

Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen Instructions and MUCH More!

THE MAGAZINE FOR LEGO® ENTHUSIASTS OF ALL AGES! Issue 16 • November 2011 $8.95 in the US Featured Builders: Guy Himber, Rod Gillies and Nathan Proudlove Interview: Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen Instructions and MUCH More! 1 82658 00024 0 Issue 16 • November 2011 Contents From the Editor .....................................................................................................................2 People An American AFOL in London ..................................................................................3 Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen: Growing Up With the LEGO Group, Part 2 ...............................................10 More Building in Billund ............................................................................................14 USS Intrepid Meets USS Intrepid .............................................................................16 Building Minifigure Customization 101: Styling Your Figure’s ‘Do ........................................................................................20 You Can Build It: MINI Nazgul ................................................................................24 Steampunk: An Introduction ................................................................................27 A Look at V&A Steamworks .....................................................................................28 Builder Profile: Morgan190 ......................................................................................33 Builder Profile: Beau Donnan .................................................................................36 -

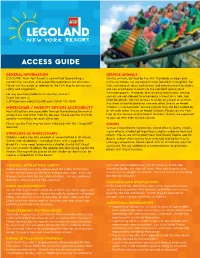

Access Guide

ACCESS GUIDE GENERAL INFORMATION SERVICE ANIMALS LEGOLAND® New York Resort is committed to providing a Service animals, defined by the ADA Standards as dogs and welcoming, inclusive, and accessible experience for all Guests. miniature horses, are welcome in most locations throughout the Please use this guide in addition to the Park Map to ensure your Park, including all retail, restaurants and entertainment locations, safety and enjoyment. and can accompany a Guest via the standard queue up to the loading point. However, due to safety restrictions, service For any questions/additional inquiries, contact: animals are not allowed to accompany a Guest on a ride. See Guest Services at chart for details. Service animals must be on a leash at all times. [email protected] | (845) 410-0290 Any show of hostile behavior towards other Guests or Model WHEELCHAIR / MOBILITY DEVICES ACCESSIBILITY Citizens is unacceptable. Service animals may not be handled by Most attractions are accessible through the entrance for manual or left with other Guests or Model Citizens. Please see the Park wheelchairs and other mobility devices. Please see the chart for Map for the Service Animal Relief Locations. Guests are expected specific instructions for each attraction. to pick-up after their service animals. Please see the Park Map for areas indicated with the “Steep Hill” SHOWS identifier. Certain shows feature loud music, sound effects, lasers, smoke, water effects, strobe lighting effects, and/or airborne theatrical STROLLERS AS WHEELCHAIRS effects. Please see LEGOLAND® New York Resort mobile app for Strollers used in lieu of a wheelchair are permitted in all venues. -

Legoland New York

LEGOLAND NEW YORK TOWN OF GOSHEN PLANNING BOARD LEAD AGENCY SEQRA FINDINGS STATEMENT WHEREAS Merlin Entertainments Group US Holdings, Inc. (the “Project Sponsor” or “Merlin Entertainments”) submitted an application for site plan, subdivision and special permit approval for a theme park and resort on approximately 150 acres of a 521.95 acre site consisting of 15 total parcels located off of Harriman Drive, as well as an application for a clearing and grading permit, known as LEGOLAND New York (“the Project”, “Proposed Project”, “Proposed Action” or “LEGOLAND New York”), to the Town of Goshen Planning Board on June 3, 2016; and WHEREAS the Town of Goshen Planning Board declared its intent to serve as Lead Agency under the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) and typed the Action as a Type I action on June 16, 2016. A Notice of Intent was circulated to the Involved Agencies on June 17, 2016; and WHEREAS after waiting the required 30 days and receiving no written objections, the Town of Goshen Planning Board assumed Lead Agency on July 21, 2016; and WHEREAS on July 21, 2016 the Planning Board adopted a SEQRA Positive Declaration requiring the submission of a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (“DEIS”); and WHEREAS the Planning Board held a public scoping session on July 21, 2016 and the scoping process culminated in the acceptance of an adopted scope, which final version incorporated the Planning Board’s required modifications on August 18, 2016 (the “Adopted Scope”); and WHEREAS the Applicant submitted a proposed DEIS on September 28, 2016, and, following the receipt of comments from the Planning Board and its consultants, submitted a revised proposed DEIS on November 3, 2016; and WHEREAS the revised DEIS was accepted by the Planning Board as complete in terms of its adequacy to commence agency and public review on November 17, 2016, subject to several revisions which were made prior to the filing and distribution of the DEIS on November 21, 2016. -

LEGO Ninjago Fight the Power of the Snakes! Brickmaster Free

FREE LEGO NINJAGO FIGHT THE POWER OF THE SNAKES! BRICKMASTER PDF DK | 56 pages | 03 Sep 2012 | Dorling Kindersley Ltd | 9781409383253 | English | London, United Kingdom Lego Ninjago - Wikipedia The Lego Brickmaster series of books are a sort of cross between a book and a Lego set. The front cover of the book forms a carry case for around Lego pieces, with the right hand side as the book. The idea is that reading, building and playing happen naturally together, which is a really clever idea. The book contains four missions, and he also found it slightly frustrating that you had to take each model apart to build the next one. But I do think that any fan of the Lego Ninjago range would be thrilled to receive this as a gift. This large format hardback has 56 pages and contains Lego pieces and two minifigures: Cole, the Earth Ninja and Lasha the meanie snake dude. The box has been slightly re-designed from previous Brickmaster releases, making it easier to keep all the pieces together. All LEGO Ninjago Fight the Power of the Snakes! Brickmaster all this is a nicely put together book and building set. But be warned — snakes are included. Suitable for age six and over. Previous 16 things I learned at Blog Camp. Next A tale of two cinema seats. Sorry, your blog cannot share posts by email. Brickmaster Ninjago: Fight the Power of the Snakes | Ninjago Wiki | Fandom The theme enjoyed popularity and success in its first year, and a further two years were commissioned before a planned discontinuation in The main focus of the line is the formation and consequent exploits and trials of a group of teenage ninjabattling against the various forces of evil. -

Celebrating 10 Years! COMIC-CON 2017 the GUIDE

¢ No.9 50 JULY SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO 2017 COMIC-CON COMIC-CON 48-page anniversary edition! SURVIVAL GUIDE THEGUIDE Celebrating 10 years! COMIC-CON 2017 THE GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................3 Marvel Heroes ....................................................................................4 Superhero Showdown .......................................................................8 Legends of DC .....................................................................................9 That Was a Comic Book? ................................................................10 Click Picks Comics ...........................................................................12 Heroes & Villains ..............................................................................14 You Know, For Kids! .........................................................................15 Comic-Con Exclusives .....................................................................17 Flights of Fantasy .............................................................................19 Level Up! ............................................................................................20 How to Speak Geek ..........................................................................21 In a Galaxy Far, Far Away ...............................................................26 The Final Frontier .............................................................................27 Invasion! ............................................................................................28 -

Coleccionistas Mundiales De Minifiguras Exclusivas

Coleccionistas Mundiales de Minifi guras Exclusivas Por Lluís Gibert Imágenes por Marc-André Bazergui, William Wong y Shawn Storoe Linked-in estilo LEGO® de Marc-André Bazergui Hay un pequeño grupo de personas cuya vida es una locura. Intentan coleccionar todas esas minifi guras que no están en los canales regulares. Minifi guras como las tarjetas de visita de empleados, y las relativas a eventos y promociones. En las siguientes páginas entenderéis por qué decidieron coleccionarlas y como intentan mejorar sus colecciones. HispaBrick Magazine: ¿Nombre, país y profesión? Marc-André Bazergui (BAZ): Montreal, Servicio de soporte técnico, IBM Canadá (también hago trabajo de consultoría independiente para eventos y community management de MINDSTORMS). Lluis Gibert (LLG): Barcelona, Ingeniero electrónico en el sector de automoción. Fundador y editor de HispaBrick Magazine®. Shawn Storoe (SS): Estados unidos, desarrollador informático. William Wong (WW): Hong Kong, Autónomo/Consultor. HispaBrick Magazine: ¿Cómo comenzaste con LEGO? WW: Comencé con el 6522 Highway Patrol que fue un regalo de cumpleaños de mis padres. Desde entonces, he continuado con LEGO® como hobby durante casi 30 años. BAZ: Volví a LEGO en 2004 al descubrir el MINDSTORMS RCX. SS: Comencé con los sets de LEGO Expert Builder cuando tenía 9 años. Mis padres me compraron el 952 Farm Tractor y directamente me enganché. Conseguí algunos sets de Expert Builder más y con el tiempo recibí el 956 Expert Builder Auto Chassis en las navidades de 1979 y me enamoré con crear cajas de cambios y construcciones con reducciones de engranajes. Me dediqué a construir vehículos con 6 ruedas con las dos del tractor y las cuatro del chasis, y solía empujar las sillas de 48 nuestro comedor.