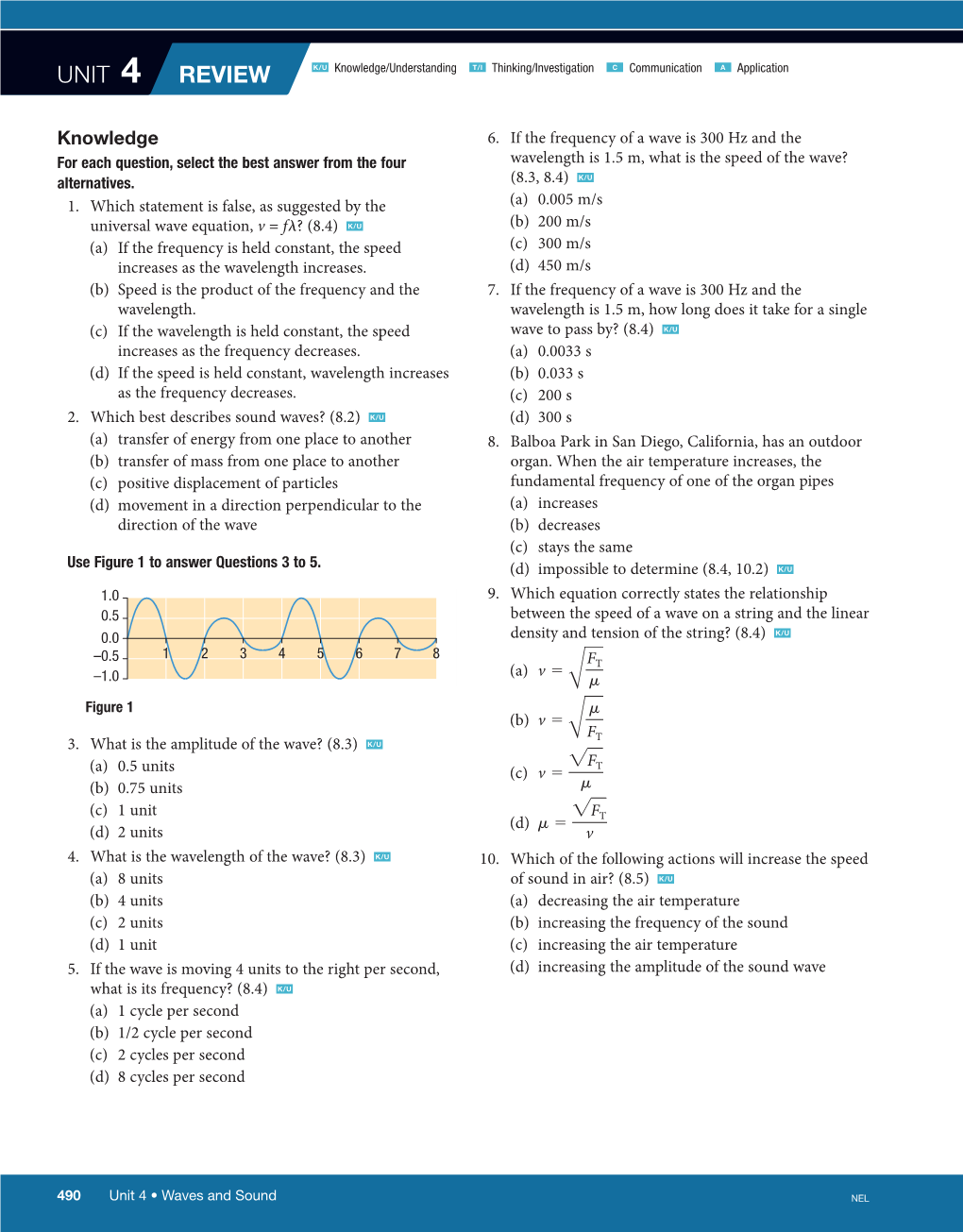

UNIT 4 Review K/U Knowledge/Understanding T/I Thinking/Investigation C Communication a Application

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tidal Resonance in the Gulf of Thailand

Ocean Sci., 15, 321–331, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/os-15-321-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Tidal resonance in the Gulf of Thailand Xinmei Cui1,2, Guohong Fang1,2, and Di Wu1,2 1First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Qingdao, 266061, China 2Laboratory for Regional Oceanography and Numerical Modelling, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266237, China Correspondence: Guohong Fang (fanggh@fio.org.cn) Received: 12 August 2018 – Discussion started: 24 August 2018 Revised: 1 February 2019 – Accepted: 18 February 2019 – Published: 29 March 2019 Abstract. The Gulf of Thailand is dominated by diurnal 1323 m. If the GOT is excluded, the mean depth of the rest tides, which might be taken to indicate that the resonant fre- of the SCS (herein called the SCS body and abbreviated as quency of the gulf is close to one cycle per day. However, SCSB) is 1457 m. Tidal waves propagate into the SCS from when applied to the gulf, the classic quarter-wavelength res- the Pacific Ocean through the Luzon Strait (LS) and mainly onance theory fails to yield a diurnal resonant frequency. In propagate in the southwest direction towards the Karimata this study, we first perform a series of numerical experiments Strait, with two branches that propagate northwestward and showing that the gulf has a strong response near one cycle per enter the Gulf of Tonkin and the GOT. The energy fluxes day and that the resonance of the South China Sea main area through the Mindoro and Balabac straits are negligible (Fang has a critical impact on the resonance of the gulf. -

Estuarine Tidal Response to Sea Level Rise: the Significance of Entrance Restriction

Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 244 (2020) 106941 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/ecss Estuarine tidal response to sea level rise: The significance of entrance restriction Danial Khojasteh a,*, Steve Hottinger a,b, Stefan Felder a, Giovanni De Cesare b, Valentin Heimhuber a, David J. Hanslow c, William Glamore a a Water Research Laboratory, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, UNSW, Sydney, NSW, Australia b Platform of Hydraulic Constructions (PL-LCH), Ecole Polytechnique F´ed´erale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland c Science, Economics and Insights Division, Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, NSW Government, Locked Bag 1002 Dangar, NSW 2309, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Estuarine environments, as dynamic low-lying transition zones between rivers and the open sea, are vulnerable Estuarine hydrodynamics to sea level rise (SLR). To evaluate the potential impacts of SLR on estuarine responses, it is necessary to examine Tidal asymmetry the altered tidal dynamics, including changes in tidal amplification, dampening, reflection (resonance), and Resonance deformation. Moving beyond commonly used static approaches, this study uses a large ensemble of idealised Idealised method estuarine hydrodynamic models to analyse changes in tidal range, tidal prism, phase lag, tidal current velocity, Ensemble modelling Cluster analysis and tidal asymmetry of restricted estuaries of varying size, entrance configuration and tidal forcing as well as three SLR scenarios. For the first time in estuarine SLR studies, data analysis and clustering approaches were employed to determine the key variables governing estuarine hydrodynamics under SLR. The results indicate that the hydrodynamics of restricted estuaries examined in this study are primarily governed by tidal forcing at the entrance and the estuarine length. -

NS-TAST-GD-013 Annex 3 Reference Paper: Analysis of Coastal Flood

ONR Expert Panel on Natural Hazards NS-TAST-GD-013 Annex 3 Reference Paper: Analysis of Coastal Flood Hazards for Nuclear Sites Expert Panel Paper No: GEN-MCFH-EP-2017-2 Sub-Panel on Meteorological & Coastal Flood Hazards October 2018 For more information contact: Office for Nuclear Regulation Building 4, Redgrave Court Merton Road Bootle L20 7HS Email: [email protected] GEN-MCFH-EP-2017-2 TRIM Ref: 2018/316283 Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. 4 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 5 2 OVERVIEW OF COASTAL FLOODING, INCLUDING EROSION AND TSUNAMI IN THE UK ........................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Mean sea level ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Vertical land movement and gravitational effects ........................................................... 7 2.3 Storm surges ..................................................................................................................8 2.4 Waves ............................................................................................................................ -

Oceanic Tides

International Hydrographie Review, Monaco, LV (2), July 1978 OCEANIC TIDES by Dr. D.E. CARTWRIGHT Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Bidston, Birkenhead, England This paper was first published in Reports on Progress in Physics, 1977 (40), and is reproduced with the kind permission of the Institute of Physics, London, who retain the copyright. ABSTRACT Tidal research has had a long history, but the outstanding problems still defeat current research techniques, including large-scale computation. The definition of the tide-generating potential, basic to all research, is reviewed in modern terms. Modern usage in analysis introduces the concept of tidal ‘ admittance ’ functions, though limited to rather narrow frequency bands. A ‘ radiational potential ’ has also been found useful in defining the parts of tidal signals which are due directly or indirectly to solar radiation. Laplace’s tidal equations ( l t e ) omit several terms from the full dyna mical equations, including the vertical acceleration. Controversies about the justification for l t e have been fairly well settled by M tt.e s ’ (1974) demonstration that, when regarded as the lowest order internal wave mode in a stratified fluid, solutions of the full equations do converge to those of l t e . Solutions in basins of simple geometry are reviewed and distinguished from attempts, mainly by P r o u d m a n , to solve for the real oceans by division into elementary strips, and from localized syntheses as Used by M u n k for the tides off California. The modern computer seemed to provide a ‘ breakthrough ’ in solving l t e for the world’s oceans, but the results of independent workers differ, mostly because of the inadequacy in their treatment of friction and for the elastic yielding of the Earth. -

Assessment of Shelf Sea Tides and Tidal Mixing Fronts in a Global Ocean Model T ⁎ Patrick G

Ocean Modelling 136 (2019) 66–84 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ocean Modelling journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ocemod Assessment of shelf sea tides and tidal mixing fronts in a global ocean model T ⁎ Patrick G. Timkoa,b, , Brian K. Arbicb,c, Patrick Hyderd, James G. Richmane, Luis Zamudioe, Enda O'Dead, Alan J. Wallcrafte, Jay F. Shriverf a Welsh Local Centre, Royal Meteorological Society, UK b Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA c Currently on sabbatical at Institut des Géosciences de L'Environnement (IGE), Grenoble, France, and Laboratoire des Etudes en Géophysique et Océanographie Spatiale (LEGOS), Toulouse, France d UK Met Office, Exeter, UK e Center for Ocean – Atmospheric Prediction Studies, Florida State University, Florida, USA f Naval Research Laboratory, Stennis Space Center, MS, USA ABSTRACT Tidal mixing fronts, which represent boundaries between stratified and tidally mixed waters, are locations of enhanced biological activity. They occur insummer shelf seas when, in the presence of strong tidal currents, mixing due to bottom friction balances buoyancy production due to seasonal heat flux. In this paper we examine the occurrence and fidelity of tidal mixing fronts in shelf seas generated within a global 3-dimensional simulation of the HYbrid Coordinate OceanModel (HYCOM) that is simultaneously forced by atmospheric fields and the astronomical tidal potential. We perform a first order assessment of shelf sea tidesinglobal HYCOM through comparison of sea surface temperature, sea surface tidal elevations, and tidal currents with observations. HYCOM was tuned to minimize errors in M2 sea surface heights in deep water. -

Seasonal Variability of Radiation Tide in Gulf of Riga

https://doi.org/10.5194/os-2020-7 Preprint. Discussion started: 27 January 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Seasonal variability of radiation tide in Gulf of Riga Vilnis Frishfelds1, Juris Sennikovs1, Uldis Bethers1, and Andrejs Timuhins1 1Faculty of Physics, Mathematics and Optometry, University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia Correspondence: Vilnis Frishfelds ([email protected]) Abstract. Diurnal oscillations of water level in Gulf of Riga are considered. It was found that there is distinct daily pattern of diurnal oscillations in certain seasons. The role of sea breeze, gravitational tides and atmospheric pressure gradient are analysed. The interference of the first two effects provide the dominant role in diurnal oscillations. The effect of gravitational tides is described both with sole tidal forcing and also in real case with atmospheric forcing and stratification. The yearly 5 variation of the declination of the Sun and stratification leads to seasonal intensification of gravitational tides in Gulf of Riga. Correlation between gravitational tide of the Sun with its radiation caused wind effects appears to be main driver of oscillations in Gulf of Riga. Daily variation of wind is primary source of S1 tidal component with a water level maximum at 18:00 UTC in Gulf of Riga. Effect of solar radiation influences also K1 and P1 tidal components which are examined, too. 1 Introduction 10 A distinct feature in Gulf of Riga is diurnal oscillations of water level despite tidal influence is negligible in Baltic sea. These oscillations are especially expressed in a relatively calm and sunny spring days. The amplitude of oscillations can reach 10 cm of water level in May, see Fig. -

Salamanca (“Little Rock City”) Conglomerate Tide- Dominated & Wave-Influenced Deltaic/Coastal Deposits Upper Devonian (Late Fammenian) Cattaraugus Formation

A3 AND B3: SALAMANCA (“LITTLE ROCK CITY”) CONGLOMERATE TIDE- DOMINATED & WAVE-INFLUENCED DELTAIC/COASTAL DEPOSITS UPPER DEVONIAN (LATE FAMMENIAN) CATTARAUGUS FORMATION JAMES H. CRAFT Engineering Geologist (retired), New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (Geology of New York, 1843) 118 INTRODUCTION On a hilltop in Rock City State Forest, three miles north of Salamanca, New York, the Salamanca Conglomerate outcrops in spectacular fashion. Part of the Upper Devonian (late Fammenian) Cattaraugus formation, the quartz-pebble conglomerate forms a five to ten-meter high escarpment and topographic bench at ~ 2200 feet elevation amid a mature cherry-maple-oak forest. In places, house- sized blocks have separated from the escarpment along orthogonal joint sets and variably “crept” downhill. Where concentrated, a maze of blocks and passageways may form so-called “rock cities”, an impressive example of which is Little Rock City. The well-cemented blocks permit extraordinary 3-D views of diverse and ubiquitous sedimentary structures and features. Six outcrop areas with the most significant exposures were logged over a four-kilometer north-south traverse. The traverse largely follows the east-facing hillside which roughly parallels the presumed paleoshore of the Devonian Catskill Sea. Extensive “bookend” outcrops at the north face (off the Rim Trail) and at the southeast perimeter (“Little Rock City” along the North Country-Finger Lakes Trail) and vertical (caprock) control allow a nearly continuous look at spatial and temporal changes in sedimentary deposits along a four-kilometer stretch of inferred late Devonian seacoast. We’ll examine several outcrops which reflect a high-energy and varied coastline as summarized below. -

Interactions Between Mean Sea Level, Tide, Surge, Waves and Flooding: Mechanisms and Contributions to Sea Level Variations at the Coast

Surveys in Geophysics (2019) 40:1603–1630 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-019-09549-5 Interactions Between Mean Sea Level, Tide, Surge, Waves and Flooding: Mechanisms and Contributions to Sea Level Variations at the Coast Déborah Idier1 · Xavier Bertin2 · Philip Thompson3 · Mark D. Pickering4 Received: 19 November 2018 / Accepted: 8 June 2019 / Published online: 26 June 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Coastal areas epitomize the notion of ‘at-risk’ territory in the context of climate change and sea level rise (SLR). Knowledge of the water level changes at the coast resulting from the mean sea level variability, tide, atmospheric surge and wave setup is critical for coastal fooding assessment. This study investigates how coastal water level can be altered by interactions between SLR, tides, storm surges, waves and fooding. The main mechanisms of interaction are identifed, mainly by analyzing the shallow water equations. Based on a literature review, the orders of magnitude of these interactions are estimated in difer- ent environments. The investigated interactions exhibit a strong spatiotemporal variability. Depending on the type of environments (e.g., morphology, hydrometeorological context), they can reach several tens of centimeters (positive or negative). As a consequence, proba- bilistic projections of future coastal water levels and fooding should identify whether inter- action processes are of leading order, and, where appropriate, projections should account for these interactions through modeling or statistical methods. Keywords Water level · Hydrodynamics · Interaction processes · Implications · Flood · Quantifcation · Modeling * Déborah Idier [email protected] Xavier Bertin [email protected] Philip Thompson [email protected] Mark D. Pickering [email protected] 1 BRGM, 3 av. -

Back to the Future II: Tidal Evolution of Four Supercontinent Scenarios

Earth Syst. Dynam., 11, 291–299, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/esd-11-291-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Back to the future II: tidal evolution of four supercontinent scenarios Hannah S. Davies1,2, J. A. Mattias Green3, and Joao C. Duarte1,2,4 1Instituto Dom Luiz (IDL), Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016, Lisbon, Portugal 2Departamento de Geologia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande, 1749-016, Lisbon, Portugal 3School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, Askew St, Menai Bridge LL59 5AB, UK 4School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3800, Australia Correspondence: Hannah S. Davies ([email protected]) Received: 7 October 2019 – Discussion started: 25 October 2019 Revised: 3 February 2020 – Accepted: 8 February 2020 – Published: 20 March 2020 Abstract. The Earth is currently 180 Myr into a supercontinent cycle that began with the break-up of Pangaea and which will end around 200–250 Myr (million years) in the future, as the next supercontinent forms. As the continents move around the planet they change the geometry of ocean basins, and thereby modify their resonant properties. In doing so, oceans move through tidal resonance, causing the global tides to be profoundly affected. Here, we use a dedicated and established global tidal model to simulate the evolution of tides during four future supercontinent scenarios. We show that the number of tidal resonances on Earth varies between one and five in a supercontinent cycle and that they last for no longer than 20 Myr. -

Dynamic Planet SSSS Notes 2021

Dynamic Planet SSSS Notes 2021 − + 2 − 2+ i. The six most abundant ions of seawater are chloride (Cl ), sodium (Na ), sulfate (SO 4 ), magnesium (Mg ), calcium (Ca2 +) , and potassium (K+ ) . By weight these ions make up about 99 percent of all sea salts.Inorganic carbon, bromide, boron, strontium, and fluoride constitute the other major dissolved substances of seawater. Of the many minor dissolved chemical constituents , inorganic phosphorus and inorganic nitrogen are among the most notable, since they are important for the growth of organisms that inhabit the oceans and seas. Seawater also contains various dissolved atmospheric gases, chiefly nitrogen, oxygen, argon, and carbon dioxide . Some other components of seawater are dissolved organic substances, such as carbohydrates and amino acids, and organic-rich particulates. These materials originate primarily in the upper 100 metres (330 feet) of the ocean, where dissolved inorganic carbon is transformed by photosynthesis into organic matter. The carbon dioxide dissolved in water from the atmosphere forms weak carbonic acid which dissolves minerals. When these minerals dissolve, they form ions, which make the water salty. While water evaporates from the ocean, the salt gets left behind. THESE SALTS MAKE UP ONLY 3.5% OF THE WEIGHT OF SEAWATER. THE OTHER 96.5% IS WATER AND OTHER MATERIAL. To make artificial seawater, add NaCl, MgCl, NaSO4, and CaCl. The weights of these most common elements per kg of seawater is Cl: 0.9989g/kg , Na: 0.556g/kg, S: 0.14g/kg, Mg: 0.068g/kg, Ca: 0.02125g/kg. Salinity of the oceans in various areas: Forchhammer put the samples through a detailed series of chemical analyses and found that the proportions of the major salts in seawater stay about the same everywhere. -

On the Tidal Dynamics of the North Sea

ON THE TIDAL DYNAMICS OF THE NORTH SEA An idealised modelling study on the role of bottom friction, the Dover Strait and tidal resonance in the North Sea. Enschede, 17 September 2010. ThiThiss master thesis was written by Jorick J. Velema BSc. aaasas fulfilment of the Master’s degree Water Engineering & Management, University of Twente, The Netherlands uuunderunder the supervision of the following committee Daily supervisor: Dr. ir. P.C. Roos (University of Twente) Graduation supervisor: Prof. dr. S.J.M.H. Hulscher (University of Twente) External supervisor: Drs. A. Stolk (Rijkswaterstaat Noordzee) Abstract This thesis is a study on the tidal dynamics of the North Sea, and in particular on the role of bottom friction, the Dover Strait and tidal resonance in the North Sea. The North Sea is one of the world’s largest shelf seas, located on the European continent. There is an extensive interest in its tide, as coastal safety, navigation and ecology are all affected by it. The tide in the North Sea is a co-oscillating response to the tides generated in the North Atlantic Ocean. Tidal waves enter the North Sea through the northern boundary with the North Atlantic Ocean and through the Dover Strait. Elements which play a possible important role on the tidal dynamics are bottom friction, basin geometry, the Dover Strait and tidal resonance. The objective of this study is to understand the large-scale amphidromic system of the North Sea, and in particular (1) the role of bottom friction, basin geometry and the Dover Strait on North Sea tide and (2) the resonant properties of the Southern Bight . -

Physical Modelling of Tidal Resonance in a Submarine

PHYSICAL MODELLING OF TIDAL RESONANCE IN A SUBMARINE CANYON by Kate Elizabeth Le Sou¨ef B.E., The University of Western Australia, 2006 B.Sc., The University of Western Australia, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Oceanography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2013 c Kate Elizabeth Le Sou¨ef,2013 Abstract The Gully, Nova Scotia (44◦N) is unique amongst studied submarine canyons ◦ poleward of 30 due to the dominance of the diurnal (K1) tidal frequency, which is subinertial at these latitudes. Length scales suggest the diurnal frequency may be resonant in the Gully. A physical model of the Gully was constructed in a tank and tidal currents were observed using a rotating table. Resonance curves were fit to measurements in the laboratory canyon for a range of stratifica- tions, background rotation rates and forcing amplitudes. Resonant frequency increased with increasing stratification and was not affected by changing back- ground rotation rates, as expected. Dense water was observed upwelling onto the continental shelf on either side of the laboratory canyon and travelled at least one canyon width along the shelf. Most of this upwelled water was pulled back into the canyon on the second half of the tidal cycle. Friction values measured in the laboratory were much higher than expected, possibly due to upwelled water surging onto the shelf on each tidal cycle, similar to a tidal bore. By scaling ob- servations from the laboratory to the ocean and assuming friction in the ocean is also affected by water travelling onto the shelf, a resonance curve for the Gully was created.