Richmond Biodiversity Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summary Report

Report by Rocket Science for The Barnes Fund This report draws on a wide range of data and on benefitted enormously from their input. Second, the experiences of a diverse sample of local we are grateful to 41 representatives from local residents to tell the story of need within our organisations who came together in focus groups community. The Barnes Fund concluded in late to discuss need in Barnes; to a number of others 2019 that we would like to commission such a who shared their views separately; to the 12 report in 2020, our 50th anniversary year, both to residents who took on the challenge of being inform our own grant making programme and as a trained as peer researchers; and to the 110 community resource. In the event the work was residents who agreed to be interviewed by them. carried out at a time when experience of Covid-19 The report could not have been written without and lockdown had sharpened many residents’ sense their willingness to provide frank feedback, of both ‘community’ and ‘need’ and there was much thoughts and ideas. And finally, we are grateful to that was being learned. At the same time, we have Rocket Science, who were chosen by the Steering been keen to take a longer-term perspective – both Group based on their expertise and relevant backwards in terms of understanding what pre- experience to carry out the research on our behalf, existing data tells us about ourselves and forwards who rose to the challenge of doing everything in terms of understanding hopes, concerns and remotely (online or via the phone) and who have expectations beyond the immediate health listened to, questioned, and directed us all before emergency. -

HA16 Rivers and Streams London's Rivers and Streams Resource

HA16 Rivers and Streams Definition All free-flowing watercourses above the tidal limit London’s rivers and streams resource The total length of watercourses (not including those with a tidal influence) are provided in table 1a and 1b. These figures are based on catchment areas and do not include all watercourses or small watercourses such as drainage ditches. Table 1a: Catchment area and length of fresh water rivers and streams in SE London Watercourse name Length (km) Catchment area (km2) Hogsmill 9.9 73 Surbiton stream 6.0 Bonesgate stream 5.0 Horton stream 5.3 Greens lane stream 1.8 Ewel court stream 2.7 Hogsmill stream 0.5 Beverley Brook 14.3 64 Kingsmere stream 3.1 Penponds overflow 1.3 Queensmere stream 2.4 Keswick avenue ditch 1.2 Cannizaro park stream 1.7 Coombe Brook 1 Pyl Brook 5.3 East Pyl Brook 3.9 old pyl ditch 0.7 Merton ditch culvert 4.3 Grand drive ditch 0.5 Wandle 26.7 202 Wimbledon park stream 1.6 Railway ditch 1.1 Summerstown ditch 2.2 Graveney/ Norbury brook 9.5 Figgs marsh ditch 3.6 Bunces ditch 1.2 Pickle ditch 0.9 Morden Hall loop 2.5 Beddington corner branch 0.7 Beddington effluent ditch 1.6 Oily ditch 3.9 Cemetery ditch 2.8 Therapia ditch 0.9 Micham road new culvert 2.1 Station farm ditch 0.7 Ravenbourne 17.4 180 Quaggy (kyd Brook) 5.6 Quaggy hither green 1 Grove park ditch 0.5 Milk street ditch 0.3 Ravensbourne honor oak 1.9 Pool river 5.1 Chaffinch Brook 4.4 Spring Brook 1.6 The Beck 7.8 St James stream 2.8 Nursery stream 3.3 Konstamm ditch 0.4 River Cray 12.6 45 River Shuttle 6.4 Wincham Stream 5.6 Marsh Dykes -

Roehampton Gate, London £5,450,000

• Stunning newly built detached house Roehampton Gate, London £5,450,000 • located in highly desirable setting close A stunning newly built detached house finished to an exceptional specification and providing extensive and flexible family to Richmond Park accommodation. Particular features include the magnificent Drawing room opening to a large terrace and huge Kitchen • High specification throughout. incorporating a large dining and living area. There is a beautiful mature garden with extensive lawn and pleasing aspects and generous gated parking. • Beautiful large garden Property Description A stunning newly built detached house finished to an exceptional specification and providing extensive and flexible family accommodation. Particular features include the magnificent Drawing room opening to a large terrace and huge Kitchen incorporating a large dining and living area. Another feature is the superb Master bedroom suite with two dressing rooms and a luxury bathroom. There is a beautiful mature garden with extensive lawn and pleasing aspects and generous gated parking. In addition to the magnificently proportioned reception rooms there is a large lower ground floor room which would make an excellent cinema/media room and also an ideal Au pair's bedroom and adjacent bathroom on this level. The property is situated in an exclusive enclave of substantial houses on the edge of Richmond Park approximately equidistant from Richmond, Barnes, Putney and Wimbledon village. This area is perfect for families seeking an accessible but semi rural environment as it is surrounded by several large green open spaces including the vast 2500 deer inhabited acres of Richmond Park (incorporating a golf course), East Sheen Common and Wimbledon Common. -

Second Local Implementation Plan

London Borough of Richmond upon Thames SECOND LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Overview............................................................................................. 6 1.1 Richmond in Context............................................................................................. 6 1.2 Richmond’s Environment...................................................................................... 8 1.3 Richmond’s People............................................................................................... 9 1.4 Richmond’s Economy ......................................................................................... 10 1.5 Transport in Richmond........................................................................................ 11 1.5.1 Road ................................................................................................................... 11 1.5.2 Rail and Underground......................................................................................... 12 1.5.3 Buses.................................................................................................................. 13 1.5.4 Cycles ................................................................................................................. 14 1.5.5 Walking ............................................................................................................... 15 1.5.6 Bridges and Structures ....................................................................................... 15 1.5.7 Noise -

The London Rivers Action Plan

The london rivers action plan A tool to help restore rivers for people and nature January 2009 www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php acknowledgements 1 Steering Group Joanna Heisse, Environment Agency Jan Hewlett, Greater London Authority Liane Jarman,WWF-UK Renata Kowalik, London Wildlife Trust Jenny Mant,The River Restoration Centre Peter Massini, Natural England Robert Oates,Thames Rivers Restoration Trust Kevin Reid, Greater London Authority Sarah Scott, Environment Agency Dave Webb, Environment Agency Support We would also like to thank the following for their support and contributions to the programme: • The Underwood Trust for their support to the Thames Rivers Restoration Trust • Valerie Selby (Wandsworth Borough Council) • Ian Tomes (Environment Agency) • HSBC's support of the WWF Thames programme through the global HSBC Climate Partnership • Thames21 • Rob and Rhoda Burns/Drawing Attention for design and graphics work Photo acknowledgements We are very grateful for the use of photographs throughout this document which are annotated as follows: 1 Environment Agency 2 The River Restoration Centre 3 Andy Pepper (ATPEC Ltd) HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This booklet is to be used in conjunction with an interactive website administered by the The River Restoration Centre (www.therrc.co.uk/lrap.php).Whilst it provides an overview of the aspirations of a range of organisations including those mentioned above, the main value of this document is to use it as a tool to find out about river restoration opportunities so that they can be flagged up early in the planning process.The website provides a forum for keeping such information up to date. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

Annual Report 2007 2008

1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 1 Richmond Borough Mind Annual Report 1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 2 April 2007-March 2008 Achievements and Performance This has been another year of change, as the Recovery Approach was Carers Support & Training introduced throughout the statutory mental health services in Richmond, We welcome the new Carers Strategy 2007-2010, a challenge to us all in Richmond Borough Mind to adapt to new, more whose aims include improved well being and quality of life for carers; making sure their contribution is outward looking, positive and empowering ways of working. recognised; increasing choice, control and information and providing training for carers and professionals. We continued to shape our service so it has a key role in In line with our strategic aims, we sought to modernise As an organisation, we have become stronger in the realising these aims: investigating the use of Carers and diversify our services throughout the year, tailoring course of the year, securing income for more frequent Vouchers, increasing the resources of our information activities at our drop-ins to attract a wide spectrum of in-house support and training for our staff, and library; and making funding bids for well being sessions. service users and fundraising for resources to move into working to strengthen our infrastructure in order to new fields like TimeBanking, Befriending and work to employ a Finance Officer and an Administrative The three support groups continued to meet in support Peer-Support groups. Later in the year, we Assistant as well as volunteers. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

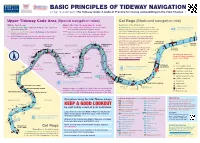

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Thistleworth Marina, Isleworth, TW7

Thistleworth Marina, Isleworth, TW7 Thistleworth Marina, TW7 £350,000 Residential Mooring A rare opportunity for a full cash buyer to acquire a converted navigable Dutch barge and highly sought after residential mooring on a marina which is owned by its residents. Mooring and maintenance fees are unusually low at £250 per month approx. and long term freehold security second to none. This secure residential mooring situated in a prime position at Thistleworth Marine on the River Thames is supplemented by a uniquely converted 65 ft. x 12 ft. foot 1923 Dutch barge conversion. Upon successful purchase of this beautiful barge you will become a shareholder of Thistleworth Marine Limited and proud owner of your own fully residential mooring on the River Thames. Located in the London Borough of Richmond adjacent to the Richmond Lock development, opposite Old Deer Park and within convenient walking distance of local shopping amenities at both St Margarets and Isleworth. The boat features superb living accommodation of an open plan kitchen/reception/diner, master cabin with en suite shower room, one further cabin with flexible use and a stunning, collapsible, teak wheelhouse. Further benefits include superb storage throughout, mains electricity, water and sewage, wiring for telephone and broadband, oil fired central heating and a glorious end of pontoon location providing stunning views of the River Thames and Isleworth Ait. Eendracht would make a comfortable home for those wanting a relaxed waterside lifestyle within a commutable distance of central London and the capability of River cruising and crossing the English Channel. Key information • Local Authority: London Borough of Hounslow • Internal Area: 517 sq. -

LBR 2007 Front Matter V5.1

1 London Bird Report No.72 for the year 2007 Accounts of birds recorded within a 20-mile radius of St Paul's Cathedral A London Natural History Society Publication Published April 2011 2 LONDON BIRD REPORT NO. 72 FOR 2007 3 London Bird Report for 2007 produced by the LBR Editorial Board Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements – Pete Lambert 5 Rarities Committee, Recorders and LBR Editors 7 Recording Arrangements 8 Map of the Area and Gazetteer of Sites 9 Review of the Year 2007 – Pete Lambert 16 Contributors to the Systematic List 22 Birds of the London Area 2007 30 Swans to Shelduck – Des McKenzie Dabbling Ducks – David Callahan Diving Ducks – Roy Beddard Gamebirds – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Divers to Shag – Ian Woodward Herons – Gareth Richards Raptors – Andrew Moon Rails – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Waders – Roy Woodward and Tim Harris Skuas to Gulls – Andrew Gardener Terns to Cuckoo – Surender Sharma Owls to Woodpeckers – Mark Pearson Larks to Waxwing – Sean Huggins Wren to Thrushes – Martin Shepherd Warblers – Alan Lewis Crests to Treecreeper – Jonathan Lethbridge Penduline Tit to Sparrows – Jan Hewlett Finches – Angela Linnell Buntings – Bob Watts Appendix I & II: Escapes & Hybrids – Martin Grounds Appendix III: Non-proven and Non-submitted Records First and Last Dates of Regular Migrants, 2007 170 Ringing Report for 2007 – Roger Taylor 171 Breeding Bird Survey in London, 2007 – Ian Woodward 181 Cannon Hill Common Update – Ron Kettle 183 The establishment of breeding Common Buzzards – Peter Oliver 199 -

Downloaded from BOLD Or Requested from Other Authors

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Towards a global DNA barcode reference library for quarantine identifcations of lepidopteran Received: 28 November 2018 Accepted: 5 April 2019 stemborers, with an emphasis on Published: xx xx xxxx sugarcane pests Timothy R. C. Lee 1, Stacey J. Anderson2, Lucy T. T. Tran-Nguyen3, Nader Sallam4, Bruno P. Le Ru5,6, Desmond Conlong7,8, Kevin Powell 9, Andrew Ward10 & Andrew Mitchell1 Lepidopteran stemborers are among the most damaging agricultural pests worldwide, able to reduce crop yields by up to 40%. Sugarcane is the world’s most prolifc crop, and several stemborer species from the families Noctuidae, Tortricidae, Crambidae and Pyralidae attack sugarcane. Australia is currently free of the most damaging stemborers, but biosecurity eforts are hampered by the difculty in morphologically distinguishing stemborer species. Here we assess the utility of DNA barcoding in identifying stemborer pest species. We review the current state of the COI barcode sequence library for sugarcane stemborers, assembling a dataset of 1297 sequences from 64 species. Sequences were from specimens collected and identifed in this study, downloaded from BOLD or requested from other authors. We performed species delimitation analyses to assess species diversity and the efectiveness of barcoding in this group. Seven species exhibited <0.03 K2P interspecifc diversity, indicating that diagnostic barcoding will work well in most of the studied taxa. We identifed 24 instances of identifcation errors in the online database, which has hampered unambiguous stemborer identifcation using barcodes. Instances of very high within-species diversity indicate that nuclear markers (e.g. 18S, 28S) and additional morphological data (genitalia dissection of all lineages) are needed to confrm species boundaries. -

Outdoor Learning Providers in the Borough

Providers of Outdoor Learning in Richmond Environmental, Friends of Parks and Residents Groups Environment Trust Website: www.environmenttrust.co.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8891 5455 Contact: Stephen James Events are advertised on http://www.environmenttrust.co.uk/whats-on Friends of Barnes Common Website: www.barnescommon.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 07855 548 404 Contact: Sharon Morgan Events are advertised on www.barnescommon.org.uk/learning Friends of Bushy and Home Parks Website: www.fbhp.org.uk Email: [email protected] Events are advertised on www.fbhp.org.uk/walksandtalks Green Corridor Land based horticultural qualifications for young people aged 14-35. Website: www.greencorridor.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 01403 713 567 Contact: Julie Docking Updated March 2016 Friends of the River Crane Environment (FORCE) Website: www.force.org.uk Email: [email protected] For walks and talks, community learning, and outdoor learning for schools in sites in the lower Crane Valley see http://e-voice.org.uk/force/calendar/view Friends of Carlisle Park Website: http://e-voice.org.uk/friendsofcarlislepark/ Ham United Group Website: www.hamunitedgroup.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 2941 Contact: Penny Frost River Thames Boat Project Educational, therapeutic and recreational cruises and activities on the River Thames. Website: www.thamesboatproject.org Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 3509 Contact: Pippa Thames Explorer Trust Website: www.thames-explorer.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8742 0057 Contact: Lorraine Conterio or Simon Clarke Summer playscheme - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/families/summer-playscheme Foreshore walks - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/foreshore-walks/ YMCA London South West Website: www.ymcalsw.org Contact: Myke Catterall Updated March 2016 Thames Young Mariners Thames Young Mariners in Ham offer outdoor learning opportunities for schools, youth groups, families and adults all year round including day and residential visits.