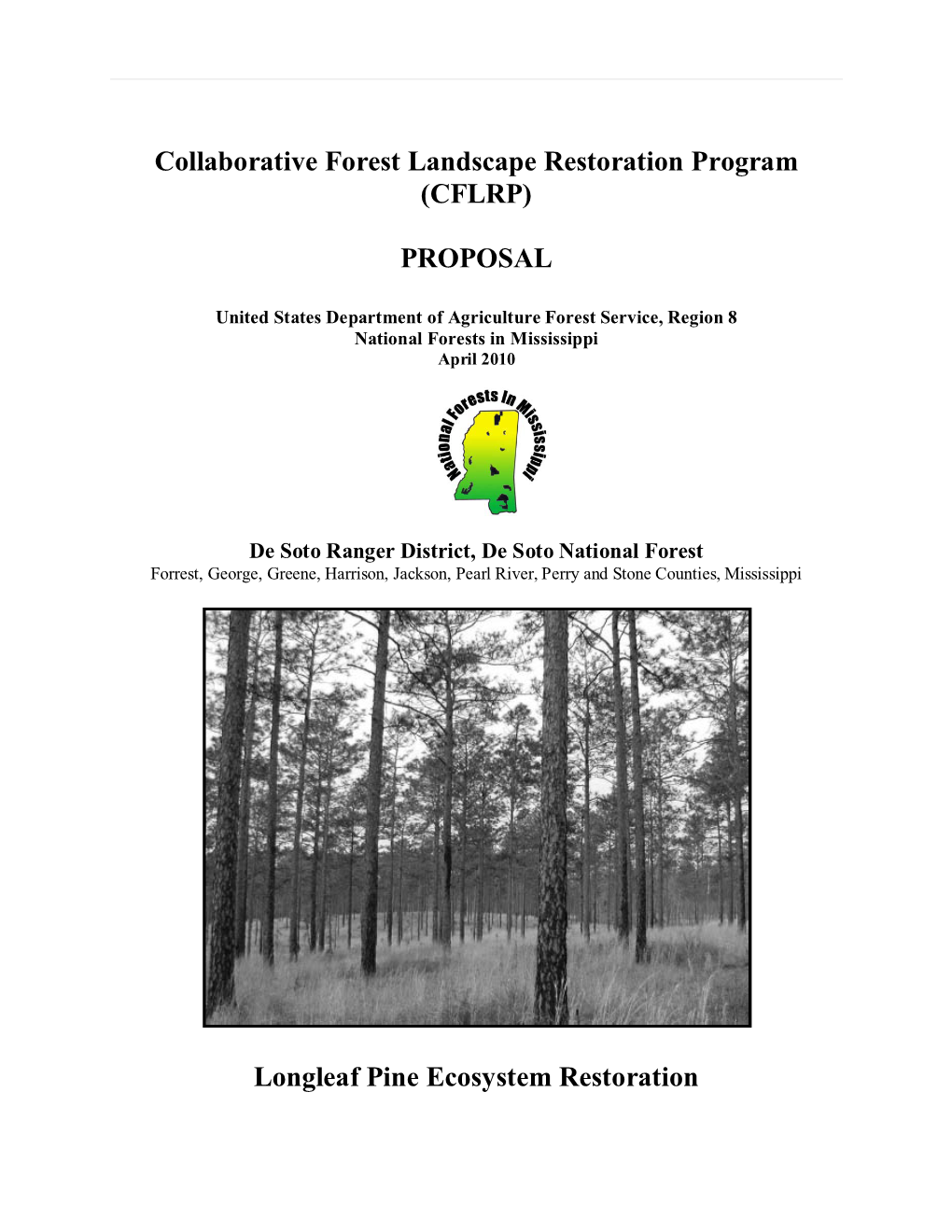

Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Our 25Th Year of Blazing a Trail for Longleaf Restoration

19005112_Longleaf-Leader-WINTER-2020_rev.qxp_Layout 1 1/9/20 10:44 AM Page 2 Our 25th Year of Blazing a Trail for Longleaf Restoration Volume Xii - issue 4 WiNTeR 2020 19005112_Longleaf-Leader-WINTER-2020_rev.qxp_Layout 1 1/9/20 10:44 AM Page 3 19005112_Longleaf-Leader-WINTER-2020_rev.qxp_Layout 1 1/9/20 10:44 AM Page 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 14 56 23 44 10 President’s Message....................................................2 LANDOWNER CORNER .......................................23 Calendar ....................................................................4 TECHNOLOGY CORNER .....................................26 Letters from the Inbox ...............................................5 REGIONAL UPDATES .........................................29 Understory Plant Spotlight........................................7 Wildlife Spotlight .....................................................8 ARTS & LITERATURE ........................................40 2019 – A Banner Year for Longleaf ..........................10 Longleaf Destinations ..............................................44 The Alliance Teaches its 100th Longleaf Academy: PEOPLE .................................................................47 A Look Back............................................................14 SUPPORT THE ALLIANCE ................................50 RESEARCH NOTES .............................................18 Heartpine ................................................................56 PUBLISHER The Longleaf Alliance, E D I T O R Carol Denhof, ASSISTANT EDITOR -

Motor Vehicle Use Map 2016-2017 De Soto Ranger District De Soto National Forest Mississippi

Motor Vehicle Use Map 2016-2017 De Soto Ranger District De Soto National Forest Mississippi United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Region Motor Vehicle Use Map 2016-2017 THE PURPOSE AND CONTENTS OPERATOR RESPONSIBILITIES EXPLANATION OF LEGEND ITEMS OF THIS MAP Operating a motor vehicle on National Forest Roads Open to Highway Legal Vehicles Only: System roads, National Forest System trails, and in This map dated 09/15/2016 shows the National Forest System roads, National Forest System trails, areas on National Forest System lands carries a These roads are open only to motor vehicles greater responsibility than operating that vehicle in a and the areas on National Forest System lands in the licensed under State law for general operation on all De Soto National Forest that are designated for city or other developed setting. Not only must the public roads within the State. motor vehicle operators know and follow all motor vehicle use pursuant to 36 CFR 212.51. The map contains a list of those designated roads, trails, applicable traffic laws, but they also need to show concern for the environment as well as other forest and areas that enumerates the types of vehicles Trails Open to Motorcycles Only: users. The misuse of motor vehicles can lead to the allowed on each route and in each area and any seasonal restrictions that apply on those routes and temporary or permanent closure of any designated These trails are open only to motorcycles. Sidecars road, trail, or area. Operators of motor vehicles are in those areas. are not permitted. -

Public Law 98-515 98Th Congress an Act

98 STAT. 2420 PUBLIC LAW 98-515—OCT. 19, 1984 Public Law 98-515 98th Congress An Act Oct. 19, 1984 To designate certain National Forest System lands in the State of Mississippi as [S. 2808] wilderness, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Mississippi United States of America in Congress assembled, That this Act may National Forest be cited as the "Mississippi National Forest Wilderness Act of 1984". Wilderness Act of 1984. National DESIGNATION OF WILDERNESS AREAS Wilderness Preservation SEC. 2. In furtherance of the purposes of the Wilderness Act (16 System. U.S.C. 1131-1136), the following lands in the State of Mississippi are National Forest System. hereby designated as wilderness and, therefore, as components of 16 use the National Wilderness Preservation System: 1132 note. (1) certain lands in the De Soto National Forest, Mississippi, which comprise approximately four thousand five hundred and sixty acres, as generally depicted on a map entitled "Proposed Black Creek Wilderness", dated January 1979, and which shall be known as the Black Creek Wilderness; and 16 use (2) certain lands in the De Soto National Forest, Mississippi, 1132 note. which comprise approximately nine hundred and forty acres, as generally depicted on a map entitled "Proposed Leaf Wilder ness", dated January 1979, and which shall be known as the Leaf Wilderness. MAPS AND DESCRIPTIONS SEC. 3. As soon as practicable after enactment of this Act, the Secretary of Agriculture shall file a map and a legal description of each wilderness area designated by this Act with the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs and the Committee on Agriculture of the United States House of Representatives and with the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry of the United States Senate. -

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,881 2nd Totals 54,922 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,750 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,935 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,987 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,867 Chilton Talladega National Forest 23,027 6th Totals 83,894 2019 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/19/2019 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,796 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 74,012 Alabama Totals 670,928 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,952 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,974,292 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,846 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,067 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass -

National Forests in Mississippi

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Land and Resource Management Plan National Forests in Mississippi Forest Supervisor’s Office – Jackson, Mississippi Bienville National Forest – Forest, Mississippi Delta National Forest – Rolling Fork, Mississippi De Soto National Forest: Chickasawhay Ranger District – Laurel, Mississippi De Soto Ranger District - Wiggins, Mississippi Holly Springs National Forest – Oxford, Mississippi (Includes the Yalobusha Unit) Homochitto National Forest – Meadville, Mississippi Tombigbee National Forest – Ackerman, Mississippi (Includes the Ackerman and Trace Units) Responsible Official: Elizabeth Agpaoa, Regional Forester Southern Region -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

People Restoring America's Forests

People Restoring America’s Forests: A Report on the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program November 2011 Executive Summary Covering one-third of the United States, forests store and filter half the nation’s water supply; provide jobs to more than a million wood products workers; absorb 20% of U.S. carbon emissions; generate $14.8 billion of recreation revenue on Forest Service lands alone; and provide habitat for thousands of wildlife and plant species across the country. Yet this year’s record mega-fires, along with 8.6 million acres of standing, beetle-killed trees, are cause for concern in our forests. A century of fire suppression, spreading pests, sprawl, and climate change are proving a perfect storm of threats to the forests our nation depends on for water, recreation, wood and other services. In an effort to preserve those critical services, the bipartisan Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration (CFLR) program was established in 2009 to foster collaborative, science-based restoration on priority forest landscapes across the U.S. The purpose of this pilot program is “…to encourage the collaborative, science-based ecosystem restoration of priority forest landscapes” (P.L. 111-11). CFLRP is unique among government programs in that it was established specifically to 1) create job stability, 2) achieve a reliable wood supply, 3) restore forest health, and 4) reduce the costs of fire suppression in overgrown forests. The ultimate goal of CFLRP is to collaboratively achieve improved forest benefits for people, water, and wildlife in a way that can be shared across the Forest Service’s 193 million acres, and beyond. -

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,881 2nd Totals 54,921 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,750 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,935 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,988 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,867 Chilton Talladega National Forest 22,986 6th Totals 83,853 2018 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/13/2018 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,796 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 74,012 Alabama Totals 670,888 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,952 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,974,292 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,846 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,067 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass -

Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,887 2nd Totals 54,927 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,749 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,934 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,987 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,983 Chilton Talladega National Forest 23,821 6th Totals 84,804 2020 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,738 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 73,954 Alabama Totals 671,786 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,860 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,979,060 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,684 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,065 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass -

2018 Annual Report: SERPPAS RCW Translocation Project

SERPPAS RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER TRANSLOCATION PROJECT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT January 2019 Authors Aliza Sager, Sager Ecological Consulting, LLC, Eglin Air Force Base Sarah Lauerman, Aves Consulting, LLC, Osceola National Forest Ralph Costa, Ralph Costa’s Woodpecker Outfit (RCWO), LLC, SERPPAS RCW Coordinator Introduction and Project History Translocations have been part of the recovery effort for the federally endangered red-cockaded woodpecker (RCW) since the late 1980s (Costa and Kennedy 1994, Hess and Costa 1995). This management technique involves moving RCWs (subadult birds) to new locations within existing populations to boost population growth rates as well as to establish new populations within their historic range. Inter-population translocations (hereafter “translocations”) are conducted between donor populations and recipient populations using criteria presented in the Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Dryobates borealis (Chesser et al 2018)) Recovery Plan: Second Revision (hereafter “Recovery Plan”) (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2003). Requirements for qualifying as donor or recipient population are described in the Recovery Plan. The importance of translocations in saving small, fragmented, and at-risk populations from extirpation has been clearly demonstrated (Rudolph et al. 1992, Haig et al. 1993, Brown and Simpkins 2004, Hedman et al. 2004, Morris and Werner 2004, Stober and Jack 2004) as well as its effectiveness in reintroducing RCWs into new habitats within its historic range (Hagan and Costa 2001, Hagan et al. 2004). In 1998, the Southern Range Translocation Cooperative (SRTC) was created to coordinate the distribution of the limited number of RCWs available for translocation in the southeastern portion of the species range (Costa and DeLotelle 2006). An annual SRTC meeting in Tallahassee, Florida allocates available RCWs in a modified version of the alternating-year model described by Saenz et al. -

Experimental Forests and Ranges of the USDA Forest Service

United States Department of Experimental Forests and Ranges Agriculture Forest Service of the USDA Forest Service Northeastern Research Station General Technical Report NE-321 Revised Abstract The USDA Forest Service has an outstanding scientific resource in the 79 Experimental Forests and Ranges that exist across the United States and its territories. These valuable scientific resources incorporate a broad range of climates, forest types, research emphases, and history. This publication describes each of the research sites within the Experimental Forests and Ranges network, providing information about history, climate, vegetation, soils, long-term data bases, research history and research products, as well as identifying collaborative opportunities, and providing contact information. The Compilers MARY BETH ADAMS, soil scientist, LINDA H. LOUGHRY, secretary, LINDA L. PLAUGHER, support services supervisor, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, Timber and Watershed Laboratory, Parsons, West Virginia. Manuscript received for publication 17 November 2003 Published by: For additional copies: USDA FOREST SERVICE USDA Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073-3294 359 Main Road September 2004 Delaware, OH 43015-8640 Revised March 2008 Fax: (740)368-0152 Revised publication available in CD-ROM only Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us Experimental Forests and Ranges of the USDA Forest Service Compiled by: Mary Beth Adams Linda Loughry Linda Plaugher Contents Introduction