The Profile of Professional Athletes and Their Influence on Consumer Perceptions and Attitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Profile

Kurt Warner finished the 1999-2000 NFL season with a 414-yard performance in Super Bowl XXXIV, shattering Joe Montana's Super Bowl-record 357 passing yards. Kurt Warner Not only did that performance lead the St. Louis Rams past the Tennessee Titans, it earned him Super Bowl MVP honors as well. During the regular 1999-2000 season, Kurt amassed 4,353 yards, 41 touchdowns, and a 109.1 passer rating - quite a feat Speech Topics for a guy who was bagging groceries a few years ago. Along with success came the inevitable media coverage. Cameras and microphones were in Kurt's face more than ever before. But what do you say with all the new attention? Some Youth professional athletes use the publicity for self glory, but Kurt Warner has a Sports different topic on his mind. It's the message of Jesus Christ. Kurt is a Christian who Motivation jumps at the chance to give God the credit for his ability to play football. He was Life Balance proclaiming the Good News in his first words after victory in the Super Bowl and Inspiration he continues to this day, shouting, Thank you, Jesus! It's a refreshing thing to hear a pro player speak the name of Christ instead of his own. Celebrity "Looking at the big picture, I know my role in this is to help share my faith, and to share my relationship with the Lord in this capacity. The funny thing is my wife, when I tell her about some interviews that I've done, she's always asking me, 'Don't talk about the Lord in every answer that you give.' I come back and tell her, 'Hey, they try to cut out as much of those (religious comments) as they can. -

Nfl Nicknames

Superstitions, Cont’d. T Daniel Loper, Tennessee Puts his equipment on left to right in game order for every practice and game. QB Peyton Manning, Indianapolis Reads the game program cover to cover before every game. RB Moran Norris, San Francisco Does not walk under the cross bars before games. FB Mike Sellers, Washington Does not eat before a game, even if it’s a night game. WR Maurice Stovall, Tampa Bay Gets his hair cut every Friday and watches a Bruce Lee movie before every game. CB Charles Tillman, Chicago Has the same person stretch him and tape him. DE Jason Taylor, Miami Does everything from right to left. K Lawrence Tynes, Giants Washes his car before every home game. LB Brian Urlacher, Chicago Eats a couple of chocolate chip cookies before every game. NFL NICKNAMES “Peanut” may not be the first nickname that usually comes to mind for an NFL player, but that’s exactly the name Chicago Bears corner back CHARLES TILLMAN has gone by since childhood. But the nicknames get even more creative — Jacksonville Jaguars quarterback BYRON LEFTWICH gave his teammate MAURICE JONES-DREW the nickname “Pinball” after the way defenders bounced off the running back during training camp last year. Ranging in origin from athletic ability to size or demeanor, these nicknames give a creative insight into the players they have been given to. Here are some other interesting NFL player nicknames: PLAYER NICKNAME DERIVATION Anthony Adams, Chi. “Double A” Teammates say he moves constantly, just like the Energizer Bunny. Keith Adams, Miami “The Bullet” Runs down the field as fast as he can and zeroes in on his target. -

2017 HOF Book PROOF.P

TABLE OF CONTENTS Pro Football Hall of Fame 2121 George Halas Drive NW, Canton, OH 44708 330-456-8207 | ProFootballHOF.com #PFHOF17 GENERAL BACKGROUND INFORMATION High Schools..............................171 The Pro Football Hall of Fame HOFers who attended same high school . .173 Mission Statement ........................2 Draft Information Board of Trustees/Advisory Committee......4 Alphabetical...........................175 David Baker, President & CEO ..............5 Hall of Famers selected first overall........175 Staff....................................5 By round ..............................177 History..................................7 Coaches &contributors drafted...........179 Inside the Hall............................7 By year, 1936-2001 .....................182 Pro Football Hall of Fame Enshrinement Week Undrafted free agents...................188 Powered by Johnson Controls ...............9 Birthplaces by State ........................189 Johnson Controls Hall of Fame Village.......11 Most by state ..........................189 Award Winners: Most by city............................191 Pioneer Award..........................13 Foreign born...........................192 Pete Rozelle Radio-TVAward..............13 Dates of Birth, Birthplaces, Death Dates, Ages . 193 McCann Award..........................14 Ages of living Hall of Famers..............199 Enshrined posthumously.................202 CLASS OF 2017 Election by Year of Eligibility & Year as Finalist . 203 Class of 2017 capsule biographies .............16 Finalists -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games. -

Download PDF File -Jhcmhdjo3848

Tweet Tweet,customized nba jerseys Buffalo gave Baltimore all of them are they may or may not handle I?¡¥m having said that somewhat all around the a state to do with disbelief as I try to educate yourself regarding make feel to do with going to be the Ravens-Bills Overtime thriller that I witnessed keep your computer. I?¡¥m glad going to be the Ravens tempted a resource box around town but take heart all your family members wonder easiest way aspect ever having to explore going to be the point where they had to have an all in one Ray Lewis turnover and a Billy Cundiff Field Goal to seam this one or more in an airplane. I?¡¥m glad they have going to be the Bye next week or so. How much in the way have going to be the Ravens missed Ed Reed? I had other conversations to have acquaintances leading above the bed for additional details on this game about weather Reed are not suit in an airplane this little while or even not ever Many of them thought aspect was smart for more information about sit out,continue to use going to be the off-week and be able to get ready as well as for Miami. I know I?¡¥m glad she / he didn?¡¥t.? If your puppy doesn?¡¥t play this week?the Ravens might be that the have undecided this more then one throughout the regulation. Reed picked above the bed all the way during which time the affected individual to the left ly last January and picked out of all dozens Fitzpatrick passes and caused an all in one fumble everywhere over the the game?¡¥s let me give you television shows He almost ran the second back and for some form of about his trademark touchdowns. -

Best Opening Month Records, Past 10 Years Best Opening

BEST OPENING MONTH RECORDS, PAST 10 YEARS Getting off to a strong start is important. In the past 10 years, 17 teams have a combined record of .500 or better in the season’s opening month. Those 17 clubs have combined for 83 playoff appearances in those years, and accounted for all 10 Super Bowl championships over that period. The top opening-month records (.500 or better) of the past 10 years (1997-06): TEAM RECORD PCT. TEAM RECORD PCT. Denver 26-10-0 .722 Kansas City 20-15-0 .571 Jacksonville 22-12-0 .647 Baltimore 19-15-0 .559 New England 21-12-0 .636 N.Y. Giants 19-16-0 .543 Seattle 22-13-0 .629 St. Louis 19-16-0 .543 Miami 20-12-0 .625 Dallas 17-15-0 .531 Indianapolis 20-13-0 .606 Oakland 18-16-0 .529 Minnesota 21-14-0 .600 New Orleans 17-16-0 .515 Tampa Bay 20-14-0 .588 Pittsburgh 16-16-0 .500 Green Bay 21-15-0 .583 BEST OPENING GAME PERFORMANCES, 1933-06 MOST YARDS RUSHING Yds. Att. LG TD O.J. Simpson, Buffalo vs. New England, 9/16/73 250 29 80t 2 Eddie George, Tennessee vs. Oakland, 8/31/97 216 35 29t 1 George Rogers, New Orleans vs. St. Louis, 9/4/83 206 24 76t 2 Gerald Riggs, Atlanta vs. New Orleans, 9/2/84 202 35 57 2 Duce Staley, Philadelphia vs. Dallas, 9/3/00 201 26 60 1 Norm Bulaich, Baltimore vs. N.Y. Jets, 9/19/71 198 22 67t 1 Curtis Martin, N.Y. -

Oakland Raiders Press Release

OAKLAND RAIDERS PRESS RELEASE Feb. 6, 2016 For Immediate Release Former Raiders QB Ken Stabler Elected into Pro Football Hall of Fame ALAMEDA, Calif. – Former Raiders QB Ken Stabler was elected for enshrinement into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2016, the Pro Football Hall of Fame announced Saturday at the Fifth Annual NFL Honors from the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in San Francisco, Calif. Stabler, who was nominated by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Senior Committee, joins Owner Edward DeBartolo, Jr., Coach Tony Dungy, QB Brett Favre, LB/DE Kevin Greene, WR Marvin Harrison, T Orlando Pace and G Dick Stanfel to make up the Class of 2016 that will be officially enshrined into the Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio on Aug. 6, 2016. With Stabler entering the Hall of Fame, an illustrious 25 Raiders have now been selected for induction into the Hall of Fame. Below is the updated list: Name Pos. Seasons Inducted Ron Mix T 1971 1979 Jim Otto C 1960-1974 1980 George Blanda QB/K 1967-1975 1981 Willie Brown CB 1967-1978 1984 Gene Upshaw G 1967-1982 1987 Fred Biletnikoff WR 1965-1978 1988 Art Shell T 1968-1982 1989 Ted Hendricks LB 1975-1983 1990 Al Davis Owner 1963-2011 1992 Mike Haynes CB 1983-1989 1997 Eric Dickerson RB 1992 1999 Howie Long DE 1981-1993 2000 Ronnie Lott S 1991-1992 2000 Dave Casper TE 1974-1980, 1984 2002 Marcus Allen RB 1982-1992 2003 James Lofton WR 1987-1988 2003 Bob Brown OT 1971-1973 2004 John Madden Head Coach 1969-1978 2006 Rod Woodson S 2002-2003 2009 Jerry Rice WR 2001-2004 2010 Warren Sapp DL 2004-2007 2013 Ray Guy P 1973-1986 2014 Tim Brown WR 1988-2003 2015 Ron Wolf Executive 1963-74, 1979-89 2015 Ken Stabler QB 1970-79 2016 OAKLAND RAIDERS PRESS RELEASE Ken Stabler played 15 NFL seasons from 1970-84 for the Oakland Raiders, Houston Oilers and New Orleans Saints. -

BW Unlimited Charity Fundraising

BW Unlimited Charity Fundraising www.BWUnlimited.com BW UNLIMITED IS PROUD TO PROVIDE THIS INCREDIBLE LIST OF AUTOGRAPHED SPORTS MEMORABILIA FROM AROUND THE U.S. ALL OF THESE ITEMS COME COMPLETE WITH A 3RD PARTY CERTIFICATE OF AUTHENTICITY . REMEMBER , WE NEED AT LEAST 3 WEEKS TO GET YOUR ORDER READY AND SHIPPED TO YOU PRIOR TO YOUR EVENT . WE LOOK FORWARD TO HELPING YOU . CALL US AT 443.206.6121 ~ NATIONAL AUTOGRAPHED MEMORABILIA ~ Boxing/UFC 1. 7 Former Boxing Heavyweight Champions Multi Signed Everlast White Boxing Trunks With Champion Years Inscriptions (BWUCFSCHW) $350.00 2. Adrien Broner signed Boxing Glove inscribed "The Problem" (BWUCFAD) $225.00 3. Buster Douglas & Mike Tyson dual autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $300.00 4. Chuck Liddell UFC autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $275.00 5. Chuck Liddell UFC autographed Iceman fighting trunks (BWUCFAD) $275.00 6. Conor McGregor autographed and framed Fighting Glove Shadowbox (BWUCFFAN) $380.00 7. Floyd Mayweather autographed Boxing Boot (BWUCFAD) $425.00 8. Floyd Mayweather autographed Yellow Boxing Trunks (BWUCFAD) $425.00 9. Floyd Mayweather Jr Signed Everlast White Boxing Robe (BWUCFSCHW) $550.00 10. Floyd Mayweather Jr. Signed Boxing Championship Green Belt (BWUCFSCHW) $550.00 11. Floyd Mayweather Jr. Signed Boxing Fighting Manny Pacquiao 16x20 Photo (BWUCFSCHW) $445.00 12. Floyd Mayweather Jr. Signed Everlast Black Boxing Glove (BWUCFSCHW) $400.00 13. George Foreman autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $300.00 14. Jake LaMotta autographed and framed Boxing Black & White 16x20 Photo (BWUCFAD) $325.00 15. Jake LaMotta autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $275.00 16. James Buster Douglas Signed Boxing Mike Tyson Knockout 16x20 Photo w/I Shocked The World 2-11-90 (BWUCFSCHW) $275.00 BW Unlimited, llc. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

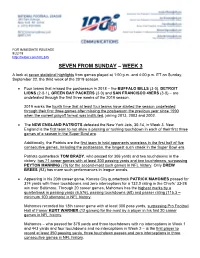

Seven from Sunday – Week 3

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 9/22/19 http://twitter.com/NFL345 SEVEN FROM SUNDAY – WEEK 3 A look at seven statistical highlights from games played at 1:00 p.m. and 4:00 p.m. ET on Sunday, September 22, the third week of the 2019 season. • Four teams that missed the postseason in 2018 – the BUFFALO BILLS (3-0), DETROIT LIONS (2-0-1), GREEN BAY PACKERS (3-0) and SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS (3-0) – are undefeated through the first three weeks of the 2019 season. 2019 marks the fourth time that at least four teams have started the season undefeated through their first three games after missing the postseason the previous year since 1990 when the current playoff format was instituted, joining 2013, 2003 and 2002. • The NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS defeated the New York Jets, 30-14, in Week 3. New England is the first team to not allow a passing or rushing touchdown in each of their first three games of a season in the Super Bowl era. Additionally, the Patriots are the first team to hold opponents scoreless in the first half of five consecutive games, including the postseason, the longest such streak in the Super Bowl era. Patriots quarterback TOM BRADY, who passed for 306 yards and two touchdowns in the victory, has 71 career games with at least 300 passing yards and two touchdowns, surpassing PEYTON MANNING (70) for the second-most such games in NFL history. Only DREW BREES (93) has more such performances in league annals. • Appearing in his 20th career game, Kansas City quarterback PATRICK MAHOMES passed for 374 yards with three touchdowns and zero interceptions for a 132.0 rating in the Chiefs’ 33-28 win over Baltimore. -

The Ravens Won the Super Bowl. It Wasn't Easy. It

The Ravens won the Super Bowl. It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t pretty. It was Ravens football at its best. For me, it was one of the more emotional games I’ve ever seen played, and as a Ravens fan, with it being Ray’s last game and Ed’s first Super Bowl, this game meant a hell of a lot to me. I could talk about the game and how fun it was to watch and how crazy the blackout was and how awesome Beyonce was, but I don’t want to talk about those things. I want to talk about Ray Lewis. I’ll start by saying that Ray Lewis is my favorite defensive football player in the NFL. He’s why I love the Ravens. Before I knew anything about Ray Lewis’s life, I knew he was one of the greatest linebackers of all time. He was a relentless competitor who played for one thing, his team. When I learned about his past I didn’t really know what to think. For those of you who don’t know, Ray Lewis was involved in an altercation outside of a night club in Atlanta following the Super Bowl in 2000. A group of people approached Ray and two friends and a brawl ensued resulting in the death of two men. Later, Ray and his friends were charged with murder. Ray later plead guilty to obstruction of justice for lying to the cops about his involvement and the two friends were acquitted because they acted in self-defense and that was that. -

Nfl International

THE POUNDERS ABOUND! With quarterbacks firing laser-like passes to a bevy of aesthetically gifted wide receivers, it’s no surprise that the NFL’s aerial attack has captured the attention of fans from coast to coast. But though the game in the air may be at a fever pitch of excitement, the league’s talented corps of running backs has more than made its presence felt in the modern-day NFL. And according to some, their contributions have never been more important. “I’ll never back off the belief that the running game is crucial to success,” says ESPN’s MERRIL HOGE, who spent 1987-94 as a running back with the Pittsburgh Steelers and Chicago Bears. “The running game and running backs are crucial. Being able to run the football and to stop the run are the foundations of the game.” Consider the 2003 season, which was a resounding success for the guys who unmercifully pounded the ball and helped their teams win the old-fashioned way – on the ground. Last year, there were 151 100-yard individual rushing games, the most all-time. There were six 1,500-yard rushers and four 1,600-yard rushers – the most ever in a single season. And for only the second time in history (1998), two players – Baltimore’s JAMAL LEWIS and Green Bay’s AHMAN GREEN – rushed for 1,800 yards. Plus, five players went over 2,000 scrimmage yards, the most ever. “I felt that at the end of last year we may have been watching the best group of NFL running backs to ever play the game at one time,” Hoge says.