The Death Penalty in North Carolina, 1910- 1961 Seth Kotch a Dissertation Submitted to the Fa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death Row U.S.A

DEATH ROW U.S.A. Summer 2017 A quarterly report by the Criminal Justice Project of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Deborah Fins, Esq. Consultant to the Criminal Justice Project NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Death Row U.S.A. Summer 2017 (As of July 1, 2017) TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATH ROW INMATES KNOWN TO LDF: 2,817 Race of Defendant: White 1,196 (42.46%) Black 1,168 (41.46%) Latino/Latina 373 (13.24%) Native American 26 (0.92%) Asian 53 (1.88%) Unknown at this issue 1 (0.04%) Gender: Male 2,764 (98.12%) Female 53 (1.88%) JURISDICTIONS WITH CURRENT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 33 Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Wyoming, U.S. Government, U.S. Military. JURISDICTIONS WITHOUT DEATH PENALTY STATUTES: 20 Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico [see note below], New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin. [NOTE: New Mexico repealed the death penalty prospectively. The men already sentenced remain under sentence of death.] Death Row U.S.A. Page 1 In the United States Supreme Court Update to Spring 2017 Issue of Significant Criminal, Habeas, & Other Pending Cases for Cases to Be Decided in October Term 2016 or 2017 1. CASES RAISING CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS First Amendment Packingham v. North Carolina, No. 15-1194 (Use of websites by sex offender) (decision below 777 S.E.2d 738 (N.C. -

Ch 5 NC Legislature.Indd

The State Legislature The General Assembly is the oldest governmental body in North Carolina. According to tradition, a “legislative assembly of free holders” met for the first time around 1666. No documentary proof, however, exists proving that this assembly actually met. Provisions for a representative assembly in Proprietary North Carolina can be traced to the Concessions and Agreements, adopted in 1665, which called for an unicameral body composed of the governor, his council and twelve delegates selected annually to sit as a legislature. This system of representation prevailed until 1670, when Albemarle County was divided into three precincts. Berkeley Precinct, Carteret Precinct and Shaftsbury Precinct were apparently each allowed five representatives. Around 1682, four new precincts were created from the original three as the colony’s population grew and the frontier moved westward. The new precincts were usually allotted two representatives, although some were granted more. Beginning with the Assembly of 1723, several of the larger, more important towns were allowed to elect their own representatives. Edenton was the first town granted this privilege, followed by Bath, New Bern, Wilmington, Brunswick, Halifax, Campbellton (Fayetteville), Salisbury, Hillsborough and Tarborough. Around 1735 Albemarle and Bath Counties were dissolved and the precincts became counties. The unicameral legislature continued until around 1697, when a bicameral form was adopted. The governor or chief executive at the time, and his council constituted the upper house. The lower house, the House of Burgesses, was composed of representatives elected from the colony’s various precincts. The lower house could adopt its own rules of procedure and elect its own speaker and other officers. -

Read Our Full Report, Death in Florida, Now

USA DEATH IN FLORIDA GOVERNOR REMOVES PROSECUTOR FOR NOT SEEKING DEATH SENTENCES; FIRST EXECUTION IN 18 MONTHS LOOMS Amnesty International Publications First published on 21 August 2017 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2017 Index: AMR 51/6736/2017 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of Contents Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 ‘Bold, positive change’ not allowed ................................................................................ -

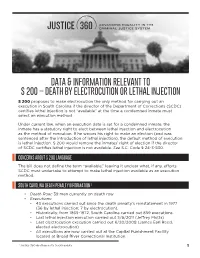

Death by Electrocution Or Lethal Injection

DATA & INFORMATION RELEVANT TO S 200 – DEATH BY ELECTROCUTION OR LETHAL INJECTION S 200 proposes to make electrocution the only method for carrying out an execution in South Carolina if the director of the Department of Corrections (SCDC) certifies lethal injection is not “available” at the time a condemned inmate must select an execution method. Under current law, when an execution date is set for a condemned inmate, the inmate has a statutory right to elect between lethal injection and electrocution as the method of execution. If he waives his right to make an election (and was sentenced after the introduction of lethal injection), the default method of execution is lethal injection. S 200 would remove the inmates’ right of election if the director of SCDC certifies lethal injection is not available. See S.C. Code § 24-3-530. CONCERNS ABOUT S 200 LANGUAGE The bill does not define the term “available,” leaving it unclear what, if any, efforts SCDC must undertake to attempt to make lethal injection available as an execution method. SOUTH CAROLINA DEATH PENALTY INFORMATION 1 • Death Row: 39 men currently on death row • Executions: • 43 executions carried out since the death penalty’s reinstatement in 1977 (36 by lethal injection; 7 by electrocution). • Historically, from 1865–1972, South Carolina carried out 859 executions. • Last lethal injection execution carried out 5/6/2011 (Jeffrey Motts) • Last electrocution execution carried out 6/20/2008 (James Earl Reed, elected electrocution) • All executions are now carried out at the Capital Punishment Facility located at Broad River Correctional Institution. 1 Justice 360 death penalty tracking data. -

PEELER: O. Max Gardner's Legacy Lives Strong

PEELER: O. Max Gardner's Legacy Lives Strong BY TIM PEELER RALEIGH, N.C. – O. Max Gardner would probably have to recuse himself from rooting for a winner this weekend. And, rest assured, the consummate politician would. That's because Gardner, the great Depression-era governor and leader of the "Shelby Dynasty" of North Carolina politics, was a pioneering football player and athlete at the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts at the turn of the 20th century. He would never pull against his alma mater. But he is also half the namesake of Gardner-Webb University, the Boiling Springs, N.C., institution that will send its football team to play against NC State Saturday evening at Carter- Finley Stadium. Kickoff is slated for 6 p.m. It may well be the first time in the history of college football that a team has faced an opponent that is named after one of its former players. More than 60 of the 246 Division I football schools (121 Football Bowl Series and 125 Football Championship Series) are named for individuals, but Gardner is believed to be the only one who played college football. There's no evidence that Austin Peay, the Rev. Alfred Cookman, P.G. Grambling, William Hofstra or Frank Park Samford – all of whom have institutions of higher learning named after them – ever donned helmet and pads during their college days. All the other schools were named after people born and raised well before college football began or most definitely not football players. So this first meeting between in-state schools might also make a little college football history. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Thursday, March 12, 2020 6:30Pm-7:50Pm Friday, March 13, 2020 8:00Am-9:20Am Friday, March 13, 2020 8:00Am-9:20Am Friday, March 1

1 Thursday, March 12, 2020 Friday, March 13, 2020 6:30pm-7:50pm 8:00am-9:20am Invited Speaker Georgian Symposium Stuart PSI CHI AND COGNITIVE KEYNOTE: STEVEN PINKER TEACHING OF PSYCHOLOGY SYMPOSIUM: FACULTY AND Thursday, March 12, 2020 STUDENT PERSPECTIVES ON BLENDED FORMAT 6:30pm-7:50pm COURSES Friday, March 13, 2020 8:00am-9:20am CHAIR: SHAUN COOK THE ELEPHANT, THE EMPEROR, AND THE MATZO BALL: CHAIR: RICHARD HARNISH COMMON KNOWLEDGE AS A RATIFIER OF HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS FACULTY AND STUDENT PERSPECTIVES ON BLENDED FORMAT COURSES STEVEN PINKER (HARVARD UNIVERSITY) Come join us for an engaging session focused on active learning Why do we veil our intentions in innuendo rather than blurting strategies that can be implemented in your blended course. them out? Why do we blush and weep? Why do we express Faculty and students will share their perspectives on a variety of outrage at public violations of decorum? Why are dictators so strategies that used active learning to improve students' learning threatened by free speech and public protests? Why don’t experience. bystanders pitch in to help? I suggest that these phenomena may be explained by the logical distinction between shared knowledge Presentations (A knows x and B knows x) and common knowledge (A knows x, B knows x, A knows that B knows x, B knows that A knows x, ad Blended Course Initiative at Penn State New Kensington infinitum). Game theory specifies that common knowledge is by Joy Krumenacker (Penn State University) necessary for coordination, in which two or more agents can cooperate for mutual benefit. -

Petitioner, V

No. 17-___ IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— WILLIAM HAROLD KELLEY, Petitioner, v. STATE OF FLORIDA, Respondent. ———— On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Florida Supreme Court ———— PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ———— LAURENCE H. TRIBE SYLVIA H. WALBOLT Of Counsel Counsel of Record CARL M. LOEB UNIVERSITY CHRIS S. COUTROULIS PROFESSOR AND PROFESSOR E. KELLY BITTICK, JR. OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW JOSEPH H. LANG, JR. HARVARD LAW SCHOOL* CARLTON FIELDS Hauser 420 JORDEN BURT, P.A. 1575 Massachusetts Avenue Corporate Center Three at Cambridge, MA 02138 International Plaza (617) 495-1767 4221 W. Boy Scout Blvd. Tampa, FL 33607 * University affiliation (813) 223-7000 noted for identification [email protected] purposes only Counsel for Petitioner May 25, 2018 WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 CAPITAL CASE QUESTION PRESENTED In Hurst v. Florida, 136 S. Ct. 616 (2016) (“Hurst I”), this Court held that Florida’s capital sentencing scheme violated the Sixth Amendment because a jury did not make the findings necessary for a death sentence. In Hurst v. State, 202 So. 3d 40 (Fla. 2016) (“Hurst II”), the Florida Supreme Court further held that under the Eighth Amendment the jury’s findings must be unanimous. Although the Florida Supreme Court held that the Hurst decisions applied retroactively, it created over sharp dissents a novel and unprecedented rule of partial retroactivity, limiting their application only to inmates whose death sentences became final after Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584 (2002). Ring, however, addressed Arizona’s capital sentencing scheme and was grounded solely on the Sixth Amendment, not the Eighth Amendment. -

Missouri's Death Penalty in 2017: the Year in Review

Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty 6320 Brookside Plaza, Suite 185; Kansas City, MO 64113 816-931-4177 www.madpmo.org Missouri’s Death Penalty in 2017: The Year in Review A year-end compilation of death penalty data for the state of Missouri. Table of Contents I. Executive Summary 2 II. Missouri Death Sentences in 2017 3 New Death Sentences 3 Unconstitutionality of Judicial Override 3 Non-Death Outcomes: Jury Rejections 4 Non-Death Outcomes: Pleas for Life Without Parole 5 III. Missouri Executions 7 Executions in Missouri and Nationally 7 Missouri’s Executed in 2017 - Mark Christeson 8 Missouri Executions by County - a Death Belt 9 Regional Similarity of Executions and Past Lynching Behaviors 10 Stays of Execution and Dates Withdrawn 12 IV. Current Death Row 13 Current Death Row by County and Demographics 13 On Death Row But Unfit for Execution 15 Granted Stay of Execution 15 Removed from Death Row - Not By Execution 16 V. Missouri’s Death Penalty in 2018 17 Pending Missouri Executions and Malpractice Concerns 17 Recent Botched Executions in Other States 17 Pending Capital Cases 18 VI. Table 1 - Missouri’s Current Death Row, 2017 19 VII. Table 2 - Missouri’s Executed 21 VIII. MADP Representatives 25 1 I. Executive Summary Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty (MADP) - a statewide organization based in Kansas City, Missouri - publishes this annual report to inform fellow citizens and elected officials about developments and related issues associated with the state’s death penalty in 2017 and recent years. This report includes information about the following death penalty developments in the state of Missouri: ● Nationally, executions and death sentences remained near historically low levels in 2017, the second fewest since 1991. -

Execution Ritual : Media Representations of Execution and the Social Construction of Public Opinion Regarding the Death Penalty

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty. Emilie Dyer 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dyer, Emilie 1987-, "Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 388. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/388 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXECUTION RITUAL: MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May, 2011 -------------------------------------------------------------- EXECUTION RITUAL : MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Brook Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2011 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director (Dr. -

Mediaguide 2021 Duke Baseb

2021 DUKE BASEBALL MEDIA GUIDE QUICK FACTS 1889 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST YEAR OF PROGRAM All-Time Program Record ...................... 2,135-1,800-34 SCHEDULE & GAME DAY GUIDE Most Victories in a Season............................. 45 (2018) 3 ROSTER & PRONUNCIATION GUIDE 4-5 BY THE NUMBERS 105 All-ACC Honorees HEAD COACH CHRIS POLLARD & STAFF 6 81 MLB Draft Selections 43 MLB Alumni 13 All-Americans 2020 REVIEW 7 8 NCAA Tournament Appearances 3 College World Series Appearances ANNUAL LEDGER 8-9 DUKE UNIVERSITY ALL-TIME LETTERWINNERS & CAPTAINS 10-16 Location ........................................................Durham, N.C. Founded ......................................1838 as Trinity College ACC CHAMPIONSHIP HISTORY 17 Enrollment .................................................................6,994 Colors ..............................Duke Blue (PMS 287) & White Nickname ......................................................... Blue Devils NCAA CHAMPIONSHIP HISTORY 18 Conference ...................................................................ACC President ...............................................Dr. Vincent Price Athletic Director ................................Dr. Kevin M. White OPPONENT SUMMARY 19-23 CHRIS POLLARD SERIES RESULTS 24-43 HEAD COACH 630-495-3 245-177 96-114 ANNUAL RESULTS All-Time At Duke ACC 44-69 Associate Head Coach ............................. Josh Jordan Assistant Coach ......................................... Jason Stein ALL-TIME STATISTICS 70-73 Pitching Coach .........................................Chris -

Did You Know? North Carolina

Did You Know? North Carolina Discover the history, geography, and government of North Carolina. The Land and Its People The state is divided into three distinct topographical regions: the Coastal Plain, the Piedmont Plateau, and the Appalachian Mountains. The Coastal Plain affords opportunities for farming, fishing, recreation, and manufacturing. The leading crops of this area are bright-leaf tobacco, peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. Large forested areas, mostly pine, support pulp manufacturing and other forest-related industries. Commercial and sport fishing are done extensively on the coast, and thousands of tourists visit the state’s many beaches. The mainland coast is protected by a slender chain of islands known as the Outer Banks. The Appalachian Mountains—including Mount Mitchell, the highest peak in eastern America (6,684 feet)—add to the variety that is apparent in the state’s topography. More than 200 mountains rise 5,000 feet or more. In this area, widely acclaimed for its beauty, tourism is an outstanding business. The valleys and some of the hillsides serve as small farms and apple orchards; and here and there are business enterprises, ranging from small craft shops to large paper and textile manufacturing plants. The Piedmont Plateau, though dotted with many small rolling farms, is primarily a manufacturing area in which the chief industries are furniture, tobacco, and textiles. Here are located North Carolina’s five largest cities. In the southeastern section of the Piedmont—known as the Sandhills, where peaches grow in abundance—is a winter resort area known also for its nationally famous golf courses and stables.