Current Ornithology Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bear River Refuge

Bear River Refuge MIGRATION MATTERS Summary Student participants increase their understanding of migration and migratory birds by playing Migration Matters. This game demonstrates the main needs Grade Level: (habitat, food/water, etc.) for migratory birds, and several of the pitfalls and 1 - 6 dangers of NOT having any of those needs readily available along the migratory flyway. Setting: Outside – pref. on grass, or large indoor Objectives - “Students will…” space with room to run. ● understand the concept of Migration / Migratory birds and be able to name at least two migratory species Time Involved: 20 – 30 min. ● indentify three reasons/barriers that explain why “Migration activity, 5 – 10 min. setup isn’t easy” (example: loss of food, habitat) Key Vocabulary: Bird ● describe how invasive species impact migratory birds Migration, Flyways, Wetland, Habitat, Invasive species Materials ● colored pipe-cleaners in rings to represent “food” Utah Grade Connections 5-6 laminated representations of wetland habitats 35 Bird Name tags (1 bird per student; 5 spp / 7 ea) 2 long ropes to delineate start/end of migration Science Core Background Social Studies Providing food, water, and habitat for migratory birds is a major portion of the US FWS & Bear River MBR’s mission. Migratory birds are historically the reason the refuge exists, and teaching the students about the many species of migratory birds that either nest or stop-off at the refuge is an important goal. The refuge hosts over 200 migratory species including large numbers of Wilson’s phalaropes, Tundra swans and most waterfowl, and also has upwards of 70 species nesting on refuge land such as White-faced ibis, American Avocet and Grasshopper sparrows. -

The Cuckoo Sheds New Light on the Scientific Mystery of Bird Migration 20 November 2015

The cuckoo sheds new light on the scientific mystery of bird migration 20 November 2015 Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen led the study with the use of miniature satellite tracking technology. In an experiment, 11 adult cuckoos were relocated from Denmark to Spain just before their winter migration to Africa was about to begin. When the birds were released more than 1,000 km away from their well-known migration route, they navigated towards the different stopover areas used along their normal route. "The release site was completely unknown to the cuckoos, yet they had no trouble finding their way back to their normal migratory route. Interestingly though, they aimed for different targets on the route, which we do not consider random. This individual and flexible choice in navigation indicates an ability to assess advantages and disadvantages of different routes, probably based on their health, age, experience or even personality traits. They evaluate their own condition and adjust their reaction to it, displaying a complicated behavior which we were able to document for the first time in migratory birds", says postdoc Mikkel Willemoes from the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen. Previously, in 2014, the Center also led a study mapping the complete cuckoo migration route from Satellite technology has made it possible for the first Denmark to Africa. Here they discovered that time to track the complete migration of a relocated during autumn the birds make stopovers in different species and reveal individual responses. Credit: Mikkel areas across Europe and Africa. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

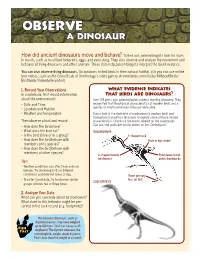

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

The Migration Strategy, Diet & Foraging Ecology of a Small

The Migration Strategy, Diet & Foraging Ecology of a Small Seabird in a Changing Environment Renata Jorge Medeiros Mirra September 2010 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University UMI Number: U516649 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516649 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declarations & Statements DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed j K>X).Vr>^. (candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 1 This thasjs is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree o f ..................... (insertMCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed . .Ate .^(candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledgedjjy explicit references. Signe .. (candidate) Date: 30/09/2010 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Migratory Bird Day Educator's Supplement

Dear Educator, elcome to the International Migratory Bird Day Educator’s Supplement. The Supplement provides activities and direction to Wadditional resources needed to teach students about migratory birds. The activities are appropriate for grade levels three through eight and can be used in classrooms as well as in informal educational settings. Birds offer virtually endless opportunities to teach and learn. For many, these singing, colorful, winged friends are the only form of wildlife that students may experience on a regular basis. Wild birds seen in backyards, suburban neighborhoods, and urban settings can connect children to the natural world in ways that captive animals cannot. You may choose to teach one activity, a selection of activities, or all five activities. If you follow the complete sequence of activities, the Supplement is structured to lead students through an Adopt-a-Bird Project. Detailed instruc- tions for the Adopt-a-Bird Project are provided (Getting Started, p. 9). Your focus on migratory birds may be limited to a single day, to each day of IMBD week, or to a longer period of time. Regardless of the time period you choose, we encourage you to consider organizing or participating in a festival for your school, organization, or community during the week of International Migratory Bird Day, the second Saturday of May. The IMBD Educator’s Supplement is a spring board into the wondrous, mysterious, and miraculous world of birds and their migration to other lands. There are many other high quality migratory bird curriculum products currently available to support materials contained in the Supplement. -

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List

Beginning Birdwatching 2021 Resource List Field Guides and how-to Birds of Illinois-Sheryl Devore and Steve Bailey The New Birder’s Guide to Birds of North America-Bill Thompson III Sibley’s Birding Basics-David Sibley Peterson Guide to Bird Identification-in 12 Steps-Howell and Sullivan Clubs and Organizations Chicago Ornithological Society-www.chicagobirder.org DuPage Birding Club-www.dupagebirding.org Evanston-North Shore Bird Club-www.ensbc.org Illinois Audubon Society-www.illinoisaudubon.org Will, Kane, Lake Cook county Audubon chapters (and others in Illinois) Illinois Ornithological Society-www.illinoisbirds.org Illinois Young Birders-(ages 9-18) monthly field trips and yearly symposiums Wild Things Conference 2021 American Birding Association- aba.org On-line Resources Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds, eBird, Birdcast Radar, Macaulay Library (sounds), Youtube series: Inside Birding: Shape, Habitat, Behavior DuPage Birding Club-Youtube channel, Mini-tutorials, Bird-O-Bingo card, DuPage hot spot descriptions Facebook: Illinois Birding Network, Illinois Rare Bird Alert, World Girl Birders, Raptor ID, What’s this Bird? Birdnote-can subscribe for informative, weekly emails-also Podcast Birdwatcher’s Digest podcasts: Out There With the Birds, Birdsense Podcasts: Laura Erickson’s For the Birds, Ray Brown’s Talkin’ Birds, American Birding Podcast (ABA) Blog: Jeff Reiter’s “Words on Birds” (meet Jeff on his monthly walks at Cantigny, see DuPage Birding Club website for schedule) Illinois Birding by County-countywiki.ilbirds.com -

Bird Migration in South Florida

BIRD MIGRATION IN SOUTH FLORIDA Many gardeners appreciate the natural world beyond plants and create landscapes with the intention of attracting and sustaining wildlife, particularly birds. Birds provide added interest, and often color, to the garden. In Miami-Dade county, there are familiar birds who reside here year round including the ubiquitous Northern Cardinal, Blue Jay and Northern Mockingbird, while others visit only during periods of migration. The fall migration of birds heading south to warmer climates for the winter usually begins in September and lasts well into November. The relatively warm weather of south Florida means that some bird species returning to their spring breeding grounds to the north can begin to be seen here as early as January, although February is generally regarded as the start of the spring migratory season. For some birds south Florida is a way station on their flight south to take advantage of warmer winter weather in the southern hemisphere. Others, such as the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher and the Palm WarBler, migrate to south Florida and make our area their winter home. The largest grouping of migratory birds seen here are the warBlers. While many have the word “warbler” in their names, others do not. They do share the distinction of being rather small birds – from the 4 ½ inch Northern Parula to the 6 inch Ovenbird – with most warblers measuring around 5 inches in length. Many warbler names reflect the color of their feathers, e.g., the Black-throated Blue Warbler and the Black-and-white Warbler. The Ovenbird gets its name from the dome shape of its nest built on the ground. -

Inferring the Wintering Distribution of The

1 1 INFERRING THE WINTERING DISTRIBUTION OF THE MEDITERRANEAN 2 POPULATIONS OF EUROPEAN STORM PETRELS (Hydrobates pelagicus ssp 3 melitensis) FROM STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS AND OBSERVATIONAL FIELD 4 DATA 5 INFIRIENDO LA DISTRIBUCIÓN INVERNAL DE LAS POBLACIONES 6 MEDITERRÁNEAS DE PAÍÑO EUROPEO (Hydrobates pelagicus ssp melitensis) A 7 PARTIR DE ANÁLISIS DE ISÓTOPOS ESTABLES Y DATOS OBSERVACIONALES 8 DE CAMPO. 9 Carlos Martínez1-5-6, Jose L. Roscales2, Ana Sanz-Aguilar3-4 and Jacob González-Solís5 10 11 1. Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, A. dos Portugueses S/N, 12 Campus do Bacanga, 65085-580, São Luís, Brazil, E-mail: [email protected] 13 2. Instituto de Química Orgánica General, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 14 Juan de la Cierva 3, 28006, Madrid, Spain, E-mail: [email protected] 15 3. Animal Demography and Ecology Group, Instituto Mediterráneo de Estudios 16 Avanzados, IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), Miquel Marquès 21, E-07190 Esporles, Islas 17 Baleares, Spain, E-mail: [email protected] 18 4. Área de Ecología, Universidad Miguel Hernández, Avenida de la Universidad s/n, 19 Edificio Torreblanca, 03202 Elche, Alicante, Spain 20 5. Institut de Recerca de la Biodiversitat (IRBio) and Departament de Biologia Evolutiva, 21 Ecologia i Ciències Ambientals, Facultat de Biologia, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. 22 Diagonal 643, 08028, Barcelona, Spain, E-mail: [email protected] 23 6. Corresponding author. 24 25 Author contributions: All authors formulated the questions; J. L. R., A. S.-A. and J. G.- 26 S. collected data; all authors supervised research; J. L. R. and J. G.-S. -

Ment for Advanoed Ornithology (Zoology 119) at the University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan, Michigan

THE LIFE HISTORY THE RUBY-THROATED HUMBBIHGBIRD .by -- J, Reuben Sandve Minneapolis, Minnesota A report of an original field study conduotsd aa a require- ment for Advanoed Ornithology (Zoology 119) at the University of Michigan Biological Station, Cheboygan, Michigan. +4 f q3 During the summer of 1943 while at the Univereity of Michigan Biological Station in Cheboygam County, Michigan, I was afforded fhe opportunity of making eon8 observations- - on the nesting habits of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archl- lochue colubrie). Observations were carried on far a two week period starting July 7 when a nest with two young waa . discovered and terminating on July 21, on whloh day the young left the nest. Although obeerrafions on a number of nests would have been more satiefaotory, no attempt was mMe to find additional nests both because of the latenese of the seaeon and the unlikehihood of finding any withln the Station area. The purpoae of this study has been to gain further in- formation on a necessarily limited phase of the life hlstory of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird which would contribute 1,n a emall way to a better understanding of its habite and behavior. Observations were made almoet exclusively from a tower blind whose floor was located four feet from the nest. A limited amount of observation was done outside of the blind with a pair of eight power binoculars. I -Nest The nest waa located in a small Whlte Birch (Betula -alba) about 22 feet from the ground and plaoed four feet out on a limb which was one-half Inch in diameter, It -

What Is a Population? an Empirical Evaluation of Some Genetic Methods for Identifying the Number of Gene Pools and Their Degree of Connectivity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 2006 What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity Robin Waples NOAA, [email protected] Oscar Gaggiotti Université Joseph Fourier, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Waples, Robin and Gaggiotti, Oscar, "What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity" (2006). Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. 463. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/463 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Molecular Ecology (2006) 15, 1419–1439 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02890.x INVITEDBlackwell Publishing Ltd REVIEW What is a population? An empirical evaluation of some genetic methods for identifying the number of gene pools and their degree of connectivity ROBIN S. WAPLES* and OSCAR GAGGIOTTI† *Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Blvd East, Seattle, WA 98112 USA, †Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (LECA), Génomique des Populations et Biodiversité, Université Joseph Fourier, Grenoble, France Abstract We review commonly used population definitions under both the ecological paradigm (which emphasizes demographic cohesion) and the evolutionary paradigm (which emphasizes reproductive cohesion) and find that none are truly operational.