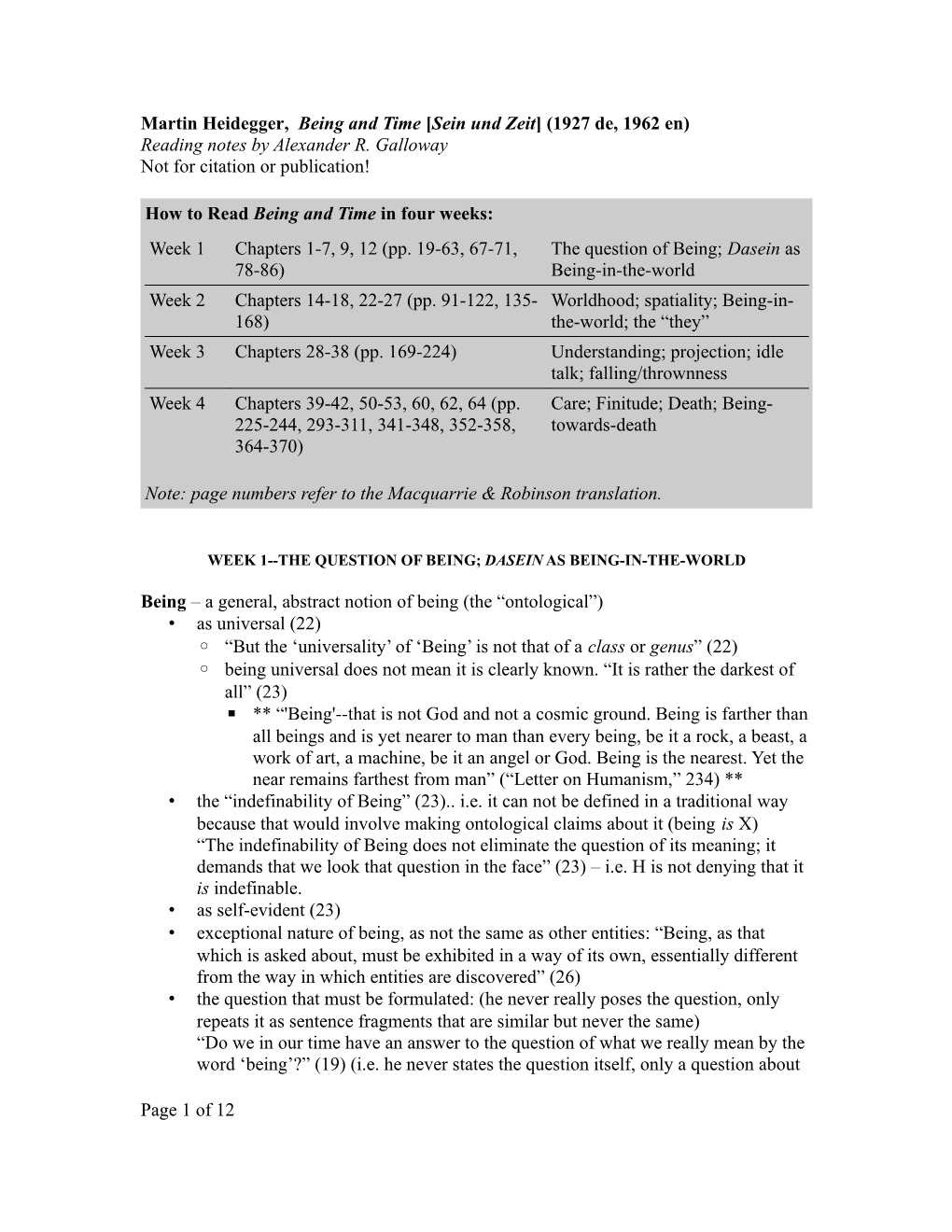

Martin Heidegger, Being and Time [Sein Und Zeit] (1927 De, 1962 En) Reading Notes by Alexander R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ontotheology? Understanding Heidegger’S Destruktion of Metaphysics* Iain Thomson

T E D U L G O E R · Internationa l Journal o f Philo sophical Studies Vol.8(3), 297–327; · T a p y u lo o r Gr & Fr ancis Ontotheology? Understanding Heidegger’s Destruktion of Metaphysics* Iain Thomson Abstract Heidegger’s Destruktion of the metaphysical tradition leads him to the view that all Western metaphysical systems make foundational claims best understood as ‘ontotheological’. Metaphysics establishes the conceptual parameters of intelligibility by ontologically grounding and theologically legitimating our changing historical sense of what is. By rst elucidating and then problematizing Heidegger’s claim that all Western metaphysics shares this ontotheological structure, I reconstruct the most important components of the original and provocative account of the history of metaphysics that Heidegger gives in support of his idiosyncratic understanding of metaphysics. Arguing that this historical narrative generates the critical force of Heidegger’s larger philosophical project (namely, his attempt to nd a path beyond our own nihilistic Nietzschean age), I conclude by briey showing how Heidegger’s return to the inception of Western metaphysics allows him to uncover two important aspects of Being’s pre-metaphysical phenomeno- logical self-manifestation, aspects which have long been buried beneath the metaphysical tradition but which are crucial to Heidegger’s attempt to move beyond our late-modern, Nietzschean impasse. Keywords: Heidegger; ontotheology; metaphysics; deconstruction; Nietzsche; nihilism Upon hearing the expression ‘ontotheology’, many philosophers start looking for the door. Those who do not may know that it was under the title of this ‘distasteful neologism’ (for which we have Kant to thank)1 that the later Heidegger elaborated his seemingly ruthless critique of Western metaphysics. -

Kierkegaard on Selfhood and Our Need for Others

Kierkegaard on Selfhood and Our Need for Others 1. Kierkegaard in a Secular Age Scholars have devoted much attention lately to Kierkegaard’s views on personal identity and, in particular, to his account of selfhood.1 Central to this account is the idea that a self is not something we automatically are. It is rather something we must become. Thus, selfhood is a goal to realize or a project to undertake.2 To put the point another way, while we may already be selves in some sense, we have to work to become real, true, or “authentic” selves.3 The idea that authentic selfhood is a project is not unique to Kierkegaard. It is common fare in modern philosophy. Yet Kierkegaard distances himself from popular ways of thinking about the matter. He denies the view inherited from Rousseau that we can discover our true selves by consulting our innermost feelings, beliefs, and desires. He also rejects the idea developed by the German Romantics that we can invent our true selves in a burst of artistic or poetic creativity. In fact, according to Kierkegaard, becom- ing an authentic self is not something we can do on our own. If we are to succeed at the project, we must look beyond ourselves for assistance. In particular, Kierkegaard thinks, we must rely on God. For God alone can provide us with the content of our real identi- ties.4 A longstanding concern about Kierkegaard arises at this point. His account of au- thentic selfhood, like his accounts of so many concepts, is religious. -

Vietnamese Existential Philosophy: a Critical Reappraisal

VIETNAMESE EXISTENTIAL PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL REAPPRAISAL A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Hi ền Thu Lươ ng May, 2009 i © Copyright 2009 by Hi ền Thu Lươ ng ii ABSTRACT Title: Vietnamese Existential Philosophy: A Critical Reappraisal Lươ ng Thu Hi ền Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Lewis R. Gordon In this study I present a new understanding of Vietnamese existentialism during the period 1954-1975, the period between the Geneva Accords and the fall of Saigon in 1975. The prevailing view within Vietnam sees Vietnamese existentialism during this period as a morally bankrupt philosophy that is a mere imitation of European versions of existentialism. I argue to the contrary that while Vietnamese existential philosophy and European existentialism share some themes, Vietnamese existentialism during this period is rooted in the particularities of Vietnamese traditional culture and social structures and in the lived experience of Vietnamese people over Vietnam’s 1000-year history of occupation and oppression by foreign forces. I also argue that Vietnamese existentialism is a profoundly moral philosophy, committed to justice in the social and political spheres. Heavily influenced by Vietnamese Buddhism, Vietnamese existential philosophy, I argue, places emphasis on the concept of a non-substantial, relational, and social self and a harmonious and constitutive relation between the self and other. The Vietnamese philosophers argue that oppressions of the mind must be liberated and that social structures that result in violence must be changed. Consistent with these ends Vietnamese existentialism proposes a multi-perspective iii ontology, a dialectical view of human thought, and a method of meditation that releases the mind to be able to understand both the nature of reality as it is and the means to live a moral, politically engaged life. -

A Hermeneutic Phenomenological Inquiry Into the Lived Experiences of Taiwanese Parachute Students

A HERMENEUTIC PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF TAIWANESE PARACHUTE STUDENTS By Benjamin T. OuYang Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillm ent Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2004 Advisory Committee: Professor Francine Hultgren, Chair and Advisor Associate Professor Jing Lin Ms. Su -Chen Mao Associate Professor Marylu McEwen Dr. Maria del Carmen Torres -Queral Copyright by Benjamin T. OuYang 2004 ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A HERMENEUTIC PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF TAIWANESE PARACHUTE STUDENTS. Benjamin T. OuYang, Doctor of Philosophy, 2004 Dissertatio n directed by: Dr. Francine H. Hultgren Department of Education Policy and Leadership The purpose of this study is to understand the lived experiences of Taiwanese parachute students, so named because of their being sent to study in the United States, fr equently unaccompanied by their parents. Significant themes are revealed through hermeneutic phenomenological methodology and developed using the powerful metaphor of landing. Seven parachute students took part in several in -depth conversations with the researcher about their experiences living in the States, immersed in the English language and the American culture. Their stories are reflective accounts, which when coupled with literary and philosophic sources, reveal the essence of this experience of living in a foreign land. Voiced by teenage and young adult parachute students, the metaphor of landing as shown in their search for establishing a home and belonging, is the slate for the writing of this work’s main themes. The research opens up to a deeper understanding of this phenomenon in such themes as foreignness, landing and surveying the area; lost in the language; homesickness; and trying to establish friendships. -

52 Philosophy in a Dark Time: Martin Heidegger and the Third Reich

52 Philosophy in a Dark Time: Martin Heidegger and the Third Reich TIMOTHY O’HAGAN Like Oscar Wilde I can resist everything except temptation. So when I re- ceived Anne Meylan’s tempting invitation to contribute to this Festschrift for Pascal Engel I accepted without hesitation, before I had time to think whether I had anything for the occasion. Finally I suggested to Anne the text of a pub- lic lecture which I delivered in 2008 and which I had shown to Pascal, who responded to it with his customary enthusiasm and barrage of papers of his own on similar topics. But when I re-read it, I realized that it had been written for the general public rather than the professional philosophers who would be likely to read this collection of essays. So what was I to do with it? I’ve decided to present it in two parts. In Part One I reproduce the original lecture, unchanged except for a few minor corrections. In Part Two I engage with a tiny fraction of the vast secondary literature which has built up over the years and which shows no sign of abating. 1. Part One: The 2008 Lecture Curtain-Raiser Let us start with two dates, 1927 and 1933. In 1927 Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (volume II) was published. So too was Martin Heidegger’s magnum opus Being and Time. In 1933 two appointments were made: Hitler as Chancellor of the German Reich and Heidegger as Rector of Freiburg University. In 1927 it was a case of sheer coincidence; in 1933 the two events were closely linked. -

The Authenticity of Faith in Kierkegaard's Philosophy

The Authenticity of Faith in Kierkegaard’s Philosophy The Authenticity of Faith in Kierkegaard’s Philosophy Edited by Tamar Aylat-Yaguri and Jon Stewart The Authenticity of Faith in Kierkegaard’s Philosophy, Edited by Tamar Aylat-Yaguri and Jon Stewart This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Layout and cover design by K.Nun Design, Denmark 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Tamar Aylat-Yaguri, Jon Stewart and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4990-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4990-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Contributors vi Introduction vii Acknowledgements xvi List of Abbreviations xvii Chapter One Jacob Golomb: Was Kierkegaard an Authentic Believer? 1 Chapter Two Shai Frogel: Acoustical Illusion as Self-Deception 12 Chapter Three Roi Benbassat: Faith as a Struggle against Ethical Self-Deception 18 Chapter Four Edward F. Mooney: A Faith that Defies Self-Deception 27 Chapter Five Darío González: Faith and the Uncertainty of Historical Experience 38 Chapter Six Jerome (Yehuda) Gellman: Constancy of Faith? Symmetry and Asymmetry in Kierkegaard’s Leap of Faith 49 Chapter Seven Peter Šajda: Does Anti-Climacus’ Ethical-Religious Theory of Selfhood Imply a Discontinuity of the Self? 60 Chapter Eight Tamar Aylat-Yaguri: Being in Truth and Being a Jew: Kierkegaard’s View of Judaism 68 Chapter Nine Jon Stewart, Kierkegaard and Hegel on Faith and Knowledge 77 Notes 93 CONTRIBUTORS Tamar Aylat-Yaguri, Department of Philosophy, Tel-Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv, P.O.B 39040, Tel-Aviv 61390, Israel. -

Temporality and Historicality of Dasein at Martin Heidegger

Sincronía ISSN: 1562-384X [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara México Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Javorská, Andrea Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Sincronía, no. 69, 2016 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=513852378011 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Filosofía Temporality and historicality of dasein at martin heidegger. Andrea Javorská [email protected] Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Eslovaquia Abstract: Analysis of Heidegger's work around historicity as an ontological problem through the existential analytic of Being Dasein. It seeks to find the significant structure of temporality represented by the historicity of Dasein. Keywords: Heidegger, Existentialism, Dasein, Temporality. Resumen: Análisis de la obra de Heidegger en tornoa la historicidad como problema ontológico a través de la analítica existencial del Ser Dasein. Se pretende encontrar la estructura significativa de temporalidad representada por la historicidad del Dasein. Palabras clave: Heidegger, Existencialismo, Dasein, Temporalidad. Sincronía, no. 69, 2016 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Martin Heidegger and his fundamental ontology shows that the question Received: 03 August 2015 Revised: 28 August 2015 of history belongs among the most fundamental questions of human Accepted: -

Heidegger Letter on Humanism Translation GROTH

Martin Heidegger LETTER ON "HUMANISM"*1 Translated by Miles Groth, PhD We still by no means think decisively enough about the essence of action. One knows action only as the bringing about of an effect, the effectiveness of which is assessed according to its usefulness. However, the essence of action is perfecting <something>. Perfecting means to unfold something in the fullness of its essence, <and in so doing> to bring it forth, producere. Therefore, <the> perfectible is actually only that which already is. Yet that which above all "is," is be[-ing]. Thinking perfects the relation of be[-ing] to the essence of man. It does not make or effect this relation. Thinking only bears it as that which is handed over to be[-ing]. This bearing consists in the fact that in thinking be[-ing] comes into language. Language is the place for be[- ing]. Man lives by its accommodation. Those who are thoughtful and those who are poetic are the overseers of these precincts. Overseeing for them is perfecting the evidence of be[-ing], insofar as they bring this up in their utterances and save it in language. Thinking does not in that way just turn into action in the sense that an effect issues from it or that it is applied <to something>. Thinking acts in that it thinks. This <kind of> action is presumably the simplest and at the same time the highest because it concerns the relation of be[-ing] to man. But all effecting 1Heidegger's marginal notes in his copies of the various editions of the lecture are included in GA 9. -

Life Is Suffering: Thrownness, Duhkha, Gaps, and the Origin of Existential-Spiritual Needs for Information

Roger Chabot The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada LIFE IS SUFFERING: THROWNNESS, DUHKHA, GAPS, AND THE ORIGIN OF EXISTENTIAL-SPIRITUAL NEEDS FOR INFORMATION Abstract: LIS scholars have spent considerable time investigating the incipient stages of information seeking: the so-called “information need” as well as a host of other motivators. A study of twenty New Kadampa Buddhists, whose experiences were collected through semi-structured interviews, sought to explore their spiritual information practices and their motivations for engaging in such behaviour. An analysis of these interviews suggests that Martin Heidegger’s concept of thrownness can be paralleled with Buddhism’s First Noble Truth and Dervin’s gap metaphor, all which identify existential-level faults as inherent to the human condition. This paper offers that it is these closely-related problematic elements of human existence that are the origin of spiritual and existential motivations for engaging in spiritual information practices. 1. Introduction A need for information can be understood as “the motivation people think and feel to seek information” (Cole, 2012, p. 3). LIS scholars have spent considerable time unravelling the complex web of needs, wants, desires, and states that have been used to describe the incipient stages of information seeking. In a similar manner, psychology of religion scholars sought to explain the origins of the motivations behind individuals’ pursuit of religious or spiritual paths, concluding that they satisfy one or more ‘fundamental’ or ‘basic’ human needs or motives (Kirkpatrick, 2013) and that they are a manner of “facilitat[ing] dealing with fundamental existential issues” (Oman, 2013, p. 36). Spiritual teachings, understood as information, play a large role in the everyday practice of spiritual paths and thus could be similarly motivated by these concerns. -

Heidegger, Being and Time

Heidegger's Being and Time 1 Karsten Harries Heidegger's Being and Time Seminar Notes Spring Semester 2014 Yale University Heidegger's Being and Time 2 Copyright Karsten Harries [email protected] Heidegger's Being and Time 3 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Ontology and Fundamental Ontology 16 3. Methodological Considerations 30 4. Being-in-the-World 43 5. The World 55 6. Who am I? 69 7. Understanding, Interpretation, Language 82 8. Care and Truth 96 9. The Entirety of Dasein 113 10. Conscience, Guilt, Resolve 128 11. Time and Subjectivity 145 12. History and the Hero 158 13. Conclusion 169 Heidegger's Being and Time 4 1. Introduction 1 In this seminar I shall be concerned with Heidegger's Being and Time. I shall refer to other works by Heidegger, but the discussion will center on Being and Time. In reading the book, some of you, especially those with a reading knowledge of German, may find the lectures of the twenties helpful, which have appeared now as volumes of the Gesamtausgabe. Many of these have by now been translated. I am thinking especially of GA 17 Einführung in die phänomenologische Forschung (1923/24); Introduction to Phenomenological Research, trans. Daniel O. Dahlstrom (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2005) GA 20 Prolegomena zur Geschichte des Zeitbegriffs (1925); History of the Concept of Time, trans. Theodore Kisiel (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1985) GA 21 Logik. Die Frage nach der Wahrheit (1925/26). Logic: The Question of Truth, trans. Thomas Sheehan GA 24 Die Grundprobleme der Phänomenologie (1927); The Basic Problems of Phenomenology, trans. -

Arendt's Critical Dialogue with Heidegger KOISHIKAWA Kazue

Thinking and Transcendence: Arendt’s Critical Dialogue with Heidegger KOISHIKAWA Kazue Adjunct Faculty, University of Tsukuba Abstract : In the introduction to The Life of the Mind: Thinking (1977), Hannah Arendt explains that it was her observation of Adolf Eichmann’s “thoughtlessness” — his inability to think — at his trial in Jerusalem that led her to reexamine the human faculty of thinking, particularly in respect to its relation to moral judgment. Yet, it is not an easy task for her readers to follow how Arendt actually constructs her arguments on this topic in this text. The purpose of this paper is to delineate Arendt’s criticisms of Heidegger in order to articulate the characteristics of her own account of thinking in relation to morality. The paper first suggests the parallelism between Heidegger’s “wonder” and Arendt’s “love” as the beginning of philosophizing, i.e., thinking, and point out a peculiar circularity in Heidegger’s account of thinking. Secondly, the paper traces Arendt’s criticism of Heidegger’s account of thinking in §18 of the LM 1. Thirdly, the paper discusses why Arendt thinks Heidegger’s account of thinking is problematic by examining Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics (1929). Finally, based on the above analyses and discussions, the paper explores the nature of Arendt’s account of thinking to show how her conception of thinking provides a basis for moral judgment. In the introduction to The Life of the Mind: Thinking (1977), Hannah Arendt explains that it was her observation of Adolf Eichmann’s “thoughtlessness” — his inability to think — at his trial in Jerusalem that led her to reexamine the human faculty of thinking, particularly in respect to its relation to moral judgment. -

Mood-Consciousness and Architecture

Mood-Consciousness and Architecture Mood-Consciousness and Architecture: A Phenomenological Investigation of Therme Vals by way of Martin Heidegger’s Interpretation of Mood A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of SCIENCE in ARCHITECTURE In the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2011 by Afsaneh Ardehali Master of Architecture, California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 1987 Committee Members: John E. Hancock (Chair) Nnamdi Elleh, Ph.D. Mood-Consciousness and Architecture abstract This thesis is an effort to unfold the disclosing power of mood as the basic character of all experiencing as well as theorizing in architecture. Having been confronted with the limiting ways of the scientific approach to understanding used in the traditional theoretical investigations, (according to which architecture is understood as a mere static object of shelter or aesthetic beauty) we turn to Martin Heidegger’s existential analysis of the meaning of Being and his new interpretation of human emotions. Translations of philosophers Eugene Gendlin, Richard Polt, and Hubert Dreyfus elucidate the deep meaning of Heidegger’s investigations and his approach to understanding mood. In contrast to our customary beliefs, which are largely informed by scientific understanding of being and emotions, this new understanding of mood clarifies our experience of architecture by shedding light on the contextualizing character of mood. In this expanded horizon of experiencing architecture, the full potentiality of mood in our experience of architecture becomes apparent in resoluteness of our new Mood-Consciousness of architecture.