European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World

Boston College Law Review Volume 60 Issue 7 Article 6 10-30-2019 Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World Lauren E. Beausoleil Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Internet Law Commons Recommended Citation Lauren E. Beausoleil, Free, Hateful, and Posted: Rethinking First Amendment Protection of Hate Speech in a Social Media World, 60 B.C.L. Rev. 2100 (2019), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol60/iss7/6 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE, HATEFUL, AND POSTED: RETHINKING FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION OF HATE SPEECH IN A SOCIAL MEDIA WORLD Abstract: Speech is meant to be heard, and social media allows for exaggeration of that fact by providing a powerful means of dissemination of speech while also dis- torting one’s perception of the reach and acceptance of that speech. Engagement in online “hate speech” can interact with the unique characteristics of the Internet to influence users’ psychological processing in ways that promote violence and rein- force hateful sentiments. Because hate speech does not squarely fall within any of the categories excluded from First Amendment protection, the United States’ stance on hate speech is unique in that it protects it. -

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report. -

Detecting White Supremacist Hate Speech Using Domain Specific

Detecting White Supremacist Hate Speech using Domain Specific Word Embedding with Deep Learning and BERT Hind Saleh, Areej Alhothali, Kawthar Moria Department of Computer Science, King Abdulaziz University,KSA, [email protected].,aalhothali,[email protected] Abstract White supremacists embrace a radical ideology that considers white people su- perior to people of other races. The critical influence of these groups is no longer limited to social media; they also have a significant effect on society in many ways by promoting racial hatred and violence. White supremacist hate speech is one of the most recently observed harmful content on social media. Traditional channels of reporting hate speech have proved inadequate due to the tremendous explosion of information, and therefore, it is necessary to find an automatic way to detect such speech in a timely manner. This research inves- tigates the viability of automatically detecting white supremacist hate speech on Twitter by using deep learning and natural language processing techniques. Through our experiments, we used two approaches, the first approach is by using domain-specific embeddings which are extracted from white supremacist corpus in order to catch the meaning of this white supremacist slang with bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) deep learning model, this approach reached arXiv:2010.00357v1 [cs.CL] 1 Oct 2020 a 0.74890 F1-score. The second approach is by using the one of the most re- cent language model which is BERT, BERT model provides the state of the art of most NLP tasks. It reached to a 0.79605 F1-score. Both approaches are tested on a balanced dataset given that our experiments were based on textual data only. -

How Does Political Hate Speech Fuel Hate Crimes in Turkey?

IJCJ&SD 9(4) 2020 ISSN 2202-8005 Planting Hate Speech to Harvest Hatred: How Does Political Hate Speech Fuel Hate Crimes in Turkey? Barbara Perry University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Canada Davut Akca University of Saskatchewan, Canada Fatih Karakus University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Canada Mehmet F Bastug Lakehead University, Canada Abstract Hate crimes against dissident groups are on the rise in Turkey, and political hate speech might have a triggering effect on this trend. In this study, the relationship between political hate speech against the Gulen Movement and the hate crimes perpetrated by ordinary people was examined through semi-structured interviews and surveys with victims. The findings suggest that a rise in political hate rhetoric targeting a given group might result in a corresponding rise in hate crimes committed against them, the effects of which have been largely overlooked in the current literature in the evolving Turkish context. Keywords Political hate speech; hate crimes; doing difference; group libel. Please cite this article as: Perry B, Akca D, Karakus F and Bastug MF (2020) Planting hate speech to harvest hatred: How does political hate speech fuel hate crimes in Turkey? International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. 9(4): 195-211. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i4.1514 Except where otherwise noted, content in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution. ISSN: 2202-8005 © The Author(s) 2020 Barbara Perry, Davut Akca, Fatih Karakus, Mehmet F Bastug: Planting Hate Speech to Harvest Hatred Introduction Hate speech used by some politicians against certain ethnic, religious, or political groups has in recent years become part of an increasing number of political campaigns and rhetoric (Amnesty International 2017). -

Online Hate Speech: Hate Or Crime?

ELSA International Online Hate Speech Competition Participant 039 Liina Laanpere, Estonia Online Hate Speech: Hate or Crime? Legal issues in the virtual world - Who is responsible for online hate speech and what legislation exists that can be applied to react, counter or punish forms of hate speech online? List of Abbreviations ACHPR – African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights ACHPR – African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights CERD – Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination ECHR – European Convention on Human Rights ECtHR – European Court of Human Rights EU – European Union ICCPR – International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ISP – Internet service providers OSCE – Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe UDHR – Universal Declaration on Human Rights UN – United Nations Introduction “Do offensive neo-Nazi skinheads have the right to propagate their odious ideology via the internet?” That question was posed by the representative of United States Mission to the OSCE in her statement at the Conference on Hate Speech. The first answer that probably pops into many minds would be “no way”. However, the speech continues: “Our courts have answered that they do. Does a person have the right to publish potentially offensive material that can be viewed by millions of people? Here again, the answer is of course.”1 That is an example of the fact that the issue of hate speech regulation is by no means black and white. Free speech is a vital human right, it is the cornerstone of any democracy. So any kind of restrictions on free speech must remain an exception. -

Race, Civil Rights, and Hate Speech in the Digital Era." Learning Race and Ethnicity: Youth and Digital Media.Edited by Anna Everett

Citation: Daniels, Jessie. “Race, Civil Rights, and Hate Speech in the Digital Era." Learning Race and Ethnicity: Youth and Digital Media.Edited by Anna Everett. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008. 129–154. doi: 10.1162/dmal.9780262550673.129 Copyright: c 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Published under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Unported 3.0 license. Race, Civil Rights, and Hate Speech in the Digital Era Jessie Daniels City University of New York—Hunter College, Urban Public Health and Sociology Introduction The emergence of the digital era has had unintended consequences for race, civil rights, and hate speech. The notion prevalent in the early days of new media, either that race does not exist on the Internet or that cyberspace represents some sort of halcyon realm of “colorblindness,” is a myth. At the same time MCI was airing its infamous commercial proclaiming “there is no race” on the Internet,1 some were already practiced at adapting white supremacy to the new online environment, creating Web sites that showcase hate speech along with more sophisticated Web sites that intentionally disguise their hateful purpose. Yet, there has been relatively little academic attention focused on racism in cyberspace.2 Here I take up the issue of racism and white supremacy online with the goal of offering a more nuanced understanding of both racism and digital media, particularly as they relate to youth. Specifically, I address two broad categories of white supremacy online: (1) overt hate Web sites that target individuals or groups, showcase racist propaganda, or offer online community for white supremacists; and (2) cloaked Web sites that intentionally seek to deceive the casual Web user. -

Protecting Electoral Integrity in the Digital Age

PROTECTING ELECTORAL INTEGRITY IN THE DIGITAL AGE The Report of the Kofi Annan Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age January 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Kofi Annan Commission on Elections and Democracy in the Digital Age ................. 1 VII. Summary of Recommendations ............................................................................................. 91 Building Capacity ...................................................................................................................... 91 Members of the Commission ............................................................................................................... 5 Building Norms ......................................................................................................................... 93 Foreword .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Action by Public Authorities ................................................................................................... 94 Action by Platform ................................................................................................................... 96 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 14 Building Capacity ............................................................................................................................... 17 Building Norms .................................................................................................................................. -

Combating Global White Supremacy in the Digital Era

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY Graduate Center 2009 Combating Global White Supremacy in the Digital Era Jessie Daniels CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_pubs/197 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 09_120_Ch09.qxd 4/21/09 5:31 AM Page 159 CHAPTER NINE Combating Global White Supremacy in the Digital Era In cyberspace the First Amendment is a local ordinance. —John Perry Barlow In 2002 Tore W. Tvedt, founder of the hate group Vigrid and a Norwegian cit- izen, was sentenced to time in prison for posting racist and anti-Semitic propa- ganda on a website. The Anti-Racism Center in Oslo filed a police complaint against Tvedt. On Vigrid’s website, Tvedt puts forward an ideology that mixes neo-Nazism, racism, and religion. Tvedt was tried and convicted in the Asker and Baerum District Court on the outskirts of Oslo. The charges were six counts of violating Norway’s antiracism law and one count each of a weapons violation and interfering with police. He was sentenced to seventy-five days in prison, with forty-five days suspended, and two years’ probation. Activists welcomed this as the first conviction for racism on the Internet in Norway. Following Tvedt’s release from prison, his Vigrid website is once again online.1 In contrast to the Norwegian response, many Americans seem to view white supremacy online as speech obviously protected under the First Amendment. -

58 the Dangers of Free Speech: Digital Hate Crimes Hate Crimes In

Ramapo Journal of Law and Society The Dangers of Free Speech: Digital Hate Crimes SARA ELJOUZI* Hate Crimes in the Digital World Hate speech on the Internet has perpetuated a free reign to attack others based on prejudices. While some may dismiss the attacks as rants reduced to a small online community, the truth is that their collective voice is motivating dangerous behavior against minority groups. However, the perpetrators of online hate speech are shielded by anonymous creators and private usernames, and, furthermore, their strongest line of defense rests in the United States Constitution: In the United States, under the First Amendment to the Constitution, online hate speech enjoys the same protections as any other form of speech. These speech protections are much more robust than that of the international community. As a result, hate organizations have found a safe-haven in the United States from which to launch their hateful messages (Henry, 2009, p. 235). The freedom afforded to online users has ultimately compromised the safety of Americans who are targets of hate speech and hate crimes. The First Amendment was created to protect citizens’ right to free speech, but it has also established a sense of invincibility for extremists who thrive in the digital world. Hate Speech and The First Amendment In June 2017, a case arose in the Supreme Court that challenged the limits of free speech. In Matal v. Tam, 582 U.S. __, the court unanimously ruled that they cannot deny the creation of trademarks that disparage certain groups or include racist symbols (Volokh, 2017, p. -

Intersectional Hate Speech Online

Platforms, Experts, Tools: Specialised Cyber-Activists Network Intersectional Hate Speech Online Project funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (2014-2020) About the Project The EU-funded project sCAN – Platforms, Experts, Tools: Specialised Cyber-Activists Network (2018- 2020), coordinated by Licra (International League Against Racism and Antisemitism), aims at gather- ing expertise, tools, methodology and knowledge on cyber hate and develop-ing transnational com- prehensive practices for identifying, analysing, reporting and counter-acting online hate speech. This project draws on the results of successful European projects already realised, for example the project “Research, Report, Remove: Countering Cyber-Hate phenomena” and “Facing Facts”, and strives to continue, emphasize and strengthen the initiatives developed by civil society for counteracting hate speech. Through cross-European cooperation, the project partners are enhancing and (further) intensifying their fruitful collaboration. The sCAN project partners are contributing to selecting and providing rel- evant automated monitoring tools to improve the detection of hateful con-tent. Another key aspect of sCAN is the strengthening of the monitoring actions (e.g. the monitoring exercises) set up by the European Commission. The project partners are also jointly gathering knowledge and findings to bet- ter identify, ex-plain and understand trends of cyber hate at a transnational level. Furthermore, this project aims to develop cross-European capacity -

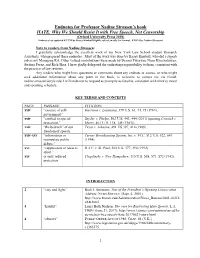

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen's Book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship

Endnotes for Professor Nadine Strossen’s book HATE: Why We Should Resist It with Free Speech, Not Censorship (Oxford University Press 2018) Endnotes last updated 4/27/18 by Kasey Kimball (lightly edited, mostly for format, 4/28/18 by Nadine Strossen) Note to readers from Nadine Strossen: I gratefully acknowledge the excellent work of my New York Law School student Research Assistants, who prepared these endnotes. Most of the work was done by Kasey Kimball, who did a superb job as my Managing RA. Other valued contributions were made by Dennis Futoryan, Nana Khachaturyan, Stefano Perez, and Rick Shea. I have gladly delegated the endnoting responsibility to them, consistent with the practice of law reviews. Any readers who might have questions or comments about any endnote or source, or who might seek additional information about any point in the book, is welcome to contact me via Email: [email protected]. I will endeavor to respond as promptly as feasible, consistent with a heavy travel and speaking schedule. KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS PAGE PASSAGE CITATION xxiv “essence of self- Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64, 74, 75 (1964). government.” xxiv “entitled to special Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443, 444 (2011) (quoting Connick v. protection.” Myers, 461 U. S. 138, 145 (1983)). xxiv “the bedrock” of our Texas v. Johnson, 491 US 397, 414 (1989). freedom of speech. xxiv-xxv “information or Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 641 manipulate public (1994). debate.” xxv “suppression of ideas is R.A.V. v. St. -

Online Hate Speech

Online hate speech Introduction into motivational causes, effects and regulatory contexts Authors: Konrad Rudnicki and Stefan Steiger Design: Milos Petrov This project is funded by the Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme of the European Union (2014-2020) The content of this manual represents the views of the author only and is their sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains. ONLINE HATE SPEECH WHAT IS ONLINE HATE SPEECH? │ 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS WHAT IS ONLINE HATE SPEECH? Defining a fuzzy concept 5 Practical definitions 6 HATE - AN EMOTION A psychological perspective 7 Why is it everywhere? 8 GLOBALIZATION OF HATE 9 VICTIMS OF HATE Gender 10 Race/ethnicity/nationality 12 Sexuality 16 HATE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE VICTIMS Consequences 17 Moderators 19 HATE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE PERPETRATORS Motivations 20 Moderators 22 HATE FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE BYSTANDERS Perceptions 23 Moderators 24 COUNTER-COMMUNICATION Definition 26 Effectiveness 27 Challenges 29 Recommendations 30 ONLINE HATE SPEECH WHAT IS ONLINE HATE SPEECH? │ 4 CONTENT MODERATION Definition 32 Effectiveness 33 Challenges 35 Recommendations 37 PSYCHOEDUCATION Definition 40 Effectiveness 41 Recommendations 42 HATE SPEECH AND POLITICAL REGULATION 43 MODES OF HATE SPEECH REGULATION 45 HATE SPEECH REGULATION IN GERMANY Legal framework 47 Recent developments 49 Reporting and sanctioning 49 HATE SPEECH REGULATION IN IRELAND Legal framework 50 Recent developments 51 Reporting