1642-1652: the Diggers and the Levellers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

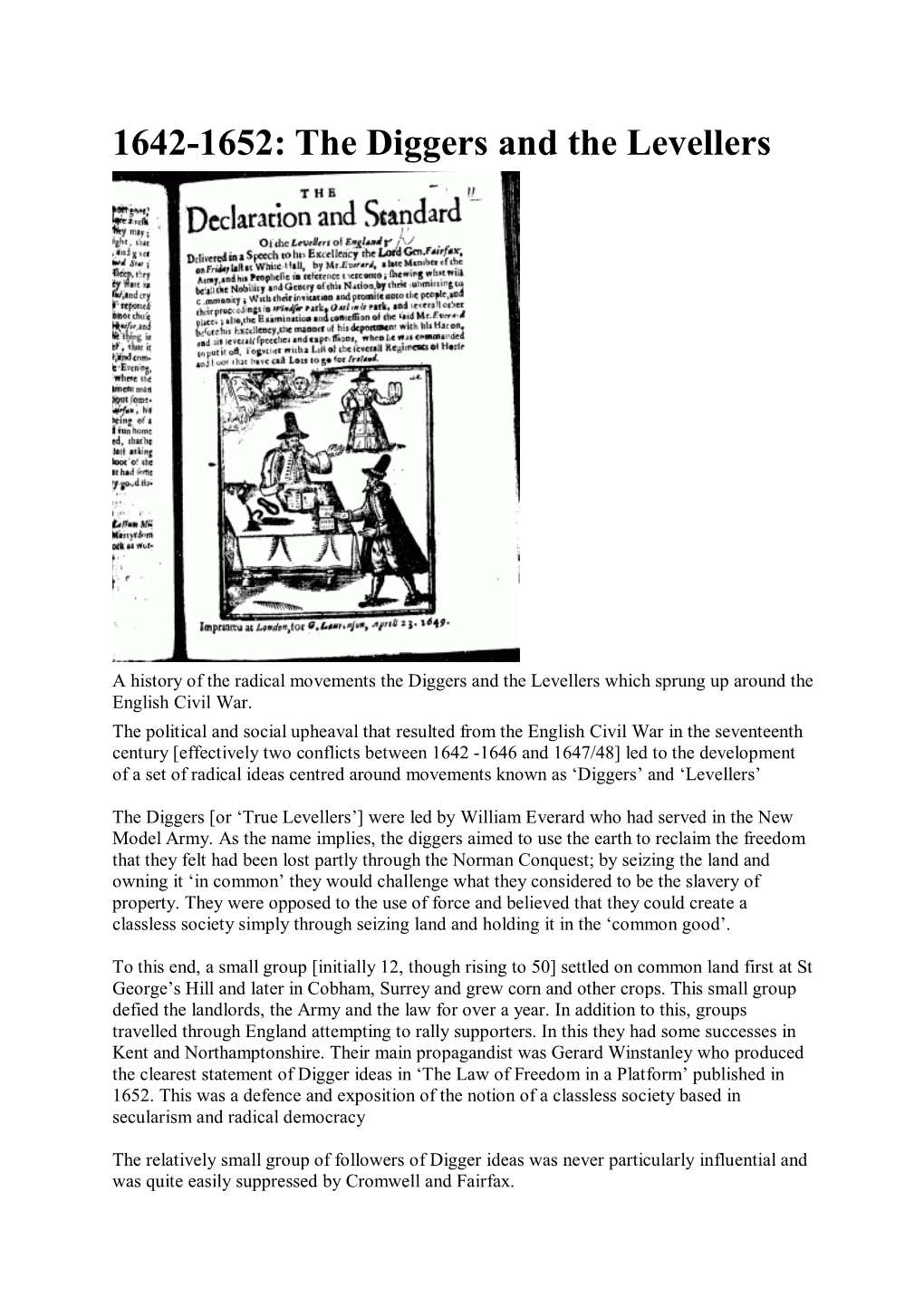

Levellers Standard

Registered Charity No: 272098 ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Tel/ Fax: 01483 532454 E-mail: [email protected] Website: ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/surreyarch Bulletin N u m b e r 3 2 8 April 1999 The True ^ Levellers Standard The State of Community opened, and-Prcfcntedtothe Sons of Men. Ferrard frififimtlej, fViSiam Everard, Richard Gtodff^o^me^ tohn Paimery Thcmoi Starrer lohnSotith, fyiUiamHoggrillj John Cottrton, Robert SawjcTy miliam TajUry Thonuu Eder, Chrifiofhtr Clifford^ Henry Sickfrfiafe, John 3arker, InhnTajlor^^. Beginning to Plant and Manure the Wade land upon George-Hill, in the Parifti of* fValtony in the Countx'of Snrrm. 'm L 0 N D 0 Ny Printed in the Yeer. M D C X LI *. Surrey: Seed-bed of Christian Socialism 350th Anniversary of the True Levellers on George's Hill Introduction Tony Benn MP In Gerrard Winstanley's pamphlet The True Levellers' Standard Advanced, published on 26th April 1649, these words appear that anticipated the conservationists and commune dwellers of today, that denounced the domination of man by man, proclaimed the equality of women and based it all on God and Nature's laws: In the beginning of Time, the great Creator, Reason, made the Earth to be a Common Treasury, to preserve Beasts, Birds, Fishes and Man, the lord that was to govern this Creation; for Man had Domination given to him, over the Beasts, Birds and Fishes; but not one word was spoken in the beginning, that one branch of manldnd should r u l e o v e r a n o t h e r . -

Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663)

Ezra’s Archives | 35 A Rhetorical Convergence: Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663) Benjamin Cohen In October 1917, following the defeat of King Charles I in the English Civil War (1642-1649) and his execution, a series of republican regimes ruled England. In 1653 Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate regime overthrew the Rump Parliament and governed England until his death in 1659. Cromwell’s regime proved fairly stable during its six year existence despite his ruling largely through the powerful New Model Army. However, the Protectorate’s rapid collapse after Cromwell’s death revealed its limited durability. England experienced a period of prolonged political instability between the collapse of the Protectorate and the restoration of monarchy. Fears of political and social anarchy ultimately brought about the restoration of monarchy under Charles I’s son and heir, Charles II in May 1660. The turmoil began when the Rump Parliament (previously ascendant in 1649-1653) seized power from Oliver Cromwell’s ineffectual son and successor, Richard, in spring 1659. England’s politically powerful army toppled the regime in October, before the Rump returned to power in December 1659. Ultimately, the Rump was once again deposed at the hands of General George Monck in February 1660, beginning a chain of events leading to the Restoration.1 In the following months Monck pragmatically maneuvered England toward a restoration and a political 1 The Rump Parliament refers to the Parliament whose membership was composed of those Parliamentarians that remained following the expulsion of members unwilling to vote in favor of executing Charles I and establishing a commonwealth (republic) in 1649. -

The Levellers' Conception of Legitimate Authority

Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades ISSN: 1575-6823 ISSN: 2340-2199 [email protected] Universidad de Sevilla España The Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority Ostrensky, Eunice The Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. 20, no. 39, 2018 Universidad de Sevilla, España Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28264625008 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative e Levellers’ Conception of Legitimate Authority A Concepção de Autoridade Legítima dos Levellers Eunice Ostrensky [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo, Brasil Abstract: is article examines the Levellers’ doctrine of legitimate authority, by showing how it emerged as a critique of theories of absolute sovereignty. For the Levellers, any arbitrary power is tyrannical, insofar as it reduces human beings to an unnatural condition. Legitimate authority is necessarily founded on the people, who creates the constitutional order and remains the locus of political power. e Levellers also contend that parliamentary representation is not the only mechanism by which the people may acquire a political being; rather the people outside Parliament are the collective agent able to transform and control institutions and policies. In this sense, the Levellers hold that a highly participative community should exert sovereignty, and that decentralized government is a means to achieve that goal. Araucaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Keywords: Limited Sovereignty, Constitution, People, Law, Rights. Filosofía, Política y Humanidades, vol. Resumo: Este artigo analisa como os Levellers desenvolveram uma doutrina da 20, no. -

A True Account of the New Model Army

Paul Z. Simons A True Account of the New Model Army 1995 Contents The Set Up . 3 The New Model Army . 4 What They Believed . 5 What They Did . 7 Where They Went . 9 Conclusion . 10 2 Revolutions have generally required some form of military activity; and mili- tary activity, in turn, generally implies an army or something like one. Armies, however, have traditionally been the offspring of the revolution, impinging little on the revolutionary politics that animate them. History provides numerous examples of this, but perhaps the most poignant is the exception that proves the rule. Recall the extreme violence with which rebellious Kronstadt was snuffed out by Bolshevism’s Finest, the Red Guards. The lesson in the massacre of the sailors and soldiers is plain, armies that defy the “institutional revolution” can expect nothing but butchery. The above statements, however, are generalizable solely to modernity, that is to say, only to the relatively contemporary era wherein the as- sumption that armies derive their mandate from the nation-state; and the nation- state in turn derives its mandate from “the people.” Prior to the hegemony of such assumptions, however, there is a stark and glaring example of an army that to a great degree was the revolution. Specifically an army that pushed the revolution as far as it could, an army that was the forum for the political development of the revolution, an army that sincerely believed that it could realize heaven on earth. Not a revolutionary army by any means, rather an army of revolutionaries, regicides, fanatics and visionaries. -

Essex Under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Summer 1-1-2012 Essex under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum James Robert McConnell Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the European History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Political History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation McConnell, James Robert, "Essex under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum" (2012). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 686. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.686 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Essex under Cromwell: Security and Local Governance in the Interregnum by James Robert McConnell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Thesis Committee: Caroline Litzenberger, Chair Thomas Luckett David A. Johnson Jesse Locker Portland State University ©2012 Abstract In 1655, Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell’s Council of State commissioned a group of army officers for the purpose of “securing the peace of the commonwealth.” Under the authority of the Instrument of Government , a written constitution not sanctioned by Parliament, the Council sent army major-generals into the counties to raise new horse militias and to support them financially with a tax on Royalists which the army officers would also collect. In counties such as Essex—the focus of this study—the major-generals were assisted in their work by small groups of commissioners, mostly local men “well-affected” to the Interregnum government. -

6Th Form Text.Pdf

THE PUTNEY DEBATES EXHIBITION ST MARY’S CHURCH PUTNEY THE LEVELLERS social rank, driven by principle rather than personal material grievance. Lilburne, in particular, had been an active campaigner for a decade. In 1637, he had been flogged, pilloried, and imprisoned for publishing pamphlets critical of the bishops; nine years later, he was imprisoned by the House of Lords on various charges of seditious conduct (and indeed was still in the Tower at the time of the Putney Debates.) Lilburne argued that true sovereignty derived from the people. Popular sovereignty, he maintained, was an inalienable right, which had only been subverted after the Norman Conquest by the new landowning class as it developed institutions and The Putney Debates are an important practices which consolidated its own landmark in English political history. power. Following the Civil War, it was At St Mary’s Church, Putney, in the not enough to replace monarchical autumn of 1647, leading members of tyranny with a system which the Army Council, which then perpetuated the power of the effectively controlled England in the landowners represented in parliament. aftermath of Charles I’s defeat in the As Lilburne told the Lords at his trial Civil War, deliberated on proposals for in 1646, “all you intended when you a radical overhaul of the constitution. set us a - fighting was merely to These proposals, which for their time unhorse and dismount our old riders were breathtaking in their and tyrants, so that you might get up revolutionary boldness, anticipated and ride in their stead.” What was many of the ideological fault lines of needed was a system which reflected the next three to four centuries. -

Activity 6. Putney Debates Define the Rights of Englishmen Source

Activity 6. Putney Debates Define the Rights of Englishmen Source: Adapted from http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/STUputneydebates.htm, accessed May 30, 2010 Background: The Putney Debates in England took place in 1647. They involved leaders of the New Model Army and Parliament that were challenging King Charles I for power. The question debated was whether ordinary men without property were entitled to the right to vote. Participants in the debate included Thomas Rainsborough, a military officer and Member of Parliament, who was considered a radical and supporter of the Leveller movement, Edward Sexby and John Wildman, military officers who were leaders of the Levellers, and Henry Ireton, who represented the senior officers in the New Model Army and argued that the vote should be based on the ownership of property. Ireton and his supporters believed that while men might have the same “natural rights” before God, they had different civil rights awarded by government. The political program of the Levellers included voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, trial by jury, and the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords. A year after the Putney Debates, Thomas Rainsborough was murdered by his opponents. Instructions: After you read and reenact the debate, imagine you are assigned to be the final speaker and write a presentation expressing your views. As a follow-up, write a 250- word editorial for an American colonial newspaper explaining how the Putney Debates and the positions taken by the Levellers will affect colonial rights. -

The Levellers Movement and Had Been Amongst the Leaders of a Mutiny Against Cromwell, Whom They Accused of Betraying the Ideals of the ‘Civil War ’

Levellers Day book cover_Levellers Day book cover 04/05/2015 08:33 Page 1 Written by PETA STEEL T H E L E THE V Published in May 2 01 5 by SERTUC E Congress House, Great Russell Street L L London WC1B 3LS E R LEVELLERS MOVEMENT 020 7467 1220 [email protected] S M O V AN ACCOUNT OF PERHAPS THE FIRST POLITICAL MOVEMENT E M TO REPRESENT THE ORDINARY PEOPLE E N T Additional sponsorship from Including THE DIGGERS AND RANTERS, ASLEF, Unison South East Region, and Unite OLIVER CROMWELL, THE AGREEMENT OF THE PEOPLE and MAGNA CARTA South East S E R T U C Printed by Upstream PUBLISHED BY SERTUC 020 7358 1344 [email protected] £2 Levellers Day book cover_Levellers Day book cover 04/05/2015 08:33 Page 2 CONTENTS THE LEVELLERS 1 THE DIGGERS AND THE RANTERS 11 THE CIVIL WARS 15 THE NEW MODEL ARMY 19 AGREEMENT OF THE PEOPLE 23 THE PUTNEY DEBATES 27 THOMAS RAINSBOROUGH 31 PETITIONS 34 THE BISHOPSGATE MUTINY 37 THE BANBURY MUTINY 38 THE MAGNA CARTA 40 OLIVER CROMWELL 43 JOHN LILBURNE 49 GERRARD WINSTANLEY 55 RICHARD OVERTON 58 KATHERINE CHIDLEY 60 KING CHARLES I 63 THE STAR CHAMBER 66 JOHN MILTON 68 Levellers Day book new_Levellers book new to print 04/05/2015 09:07 Page 1 FOREWORD THERE’S little to disagree with the Levellers over: “they wanted a democracy where there was no King, and a reformed House of Commons that represented the people, and not the vested interests of the ruling classes ”. -

Why Did Cromwell's New Model Army Win the Civil War?

Why did Cromwell’s New Model Army win the Civil War? • At the start of the civil war, the King’s armies were much better equipped. It took a while for Parliament to gather money through tax. After this got going, Parliament’s New Model Army made huge improvements. There were only four major battles during the Civil War: • 1642 Edgehill (near Birmingham). Indecisive, but the King came out on top. • 1644 Marston Moor (Yorkshire). Parliament won. • 1645 Naseby (Northamptonshire) Cromwell’s New Model Army (for Parliament) won. • 1648 Preston (North West of England). Cromwell’s armies defeated the Royalists. This was the last major battle before Charles I was executed. TASK: Answer these questions in full sentences. There are 14 possible marks. Subheading: The Battle of Edgehill 1. When, where and why was the battle held? (3 marks). 2. Give two reasons why the king’s army won. (2 marks). 3. How does Sources C disagree with Source B about the outcome of the battle? WHY do they disagree? (What is the PURPOSE of Source C?) (2 marks). Subheading: The Battle of Marston Moor 4. Which city was being besieged in 1644 by Parliamentarians? (1 mark). 5. Who did Charles send a letter to in order to help this city? (1 mark). 6. How did Prince Rupert avoid battle with the Parliamentary army under Oliver Cromwell? (1 mark). 7. Prince Rupert then decided to risk battle with the Parliamentarians on 2 July, 1644. Give two reasons why the Royalists lost this battle. (2 marks). 8. What can you learn about Cromwell’s military leadership in Source D? (Use a quote to support your answer). -

The Making of Englishmen Studies in the History of Political Thought

The Making of Englishmen Studies in the History of Political Thought Edited by Terence Ball, Arizona State University JÖrn Leonhard, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg Wyger Velema, University of Amsterdam Advisory Board Janet Coleman, London School of Economics and Political Science, UK Vittor Ivo Comparato, University of Perugia, Italy Jacques Guilhaumou, CNRS, France John Marshall, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA Markku Peltonen, University of Helsinki, Finland VOLUME 8 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ship The Making of Englishmen Debates on National Identity 1550–1650 By Hilary Larkin LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www. knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Titian (c1545) Portrait of a Young Man (The Young Englishman). Galleria Palatina (Palazzo Pitti), Florence, Italy. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Larkin, Hilary. The making of Englishmen : debates on national identity, 1550-1650 / by Hilary Larkin. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The militia of London, 1641-1649 Nagel, Lawson Chase The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 THE MILITIA OF LONDON, 16Lf].16Lt9 by LAWSON CHASE NAGEL A thesis submitted in the Department of History, King' a Co].].ege, University of Lox4on for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 1982 2 ABSTBAC The Trained Bands and. -

Putney Started Life As a Small Dwelling by the River Thames, and Has

THE CENTRE OF PUTNEY SINCE 1990 1684 1883 The Waterman School in Putney is founded in by Former Prime Minister Clement Attlee a London merchant as a token of his gratitude for 1729 is born in Putney. being saved from drowning by a Putney Waterman. An Act of Parliament is passed due to the efforts of Sir Robert Walpole and the original timber Putney Bridge is eventually built in 1729. Only the second bridge to be built across the 1880 Thames in London after London Bridge. 1990 Putney Bridge underground station opens, with Putney Exchange opens in May 1990. The mall East Putney following in 1889. Both were served costs £40million to build, and is bought 5 years by steam locomotives until electrification in 1905. later by our current owners. Designed by Chapman Taylor, with Stained Glass windows designed by Alan Younger, famous in his field. 2015 1302 For the first time in history the Putney started life as a small dwelling by the river Putney church near the bridge is dedicated 1846 men and women’s Oxford & to St Mary, built originally as a chapel of Cambridge boat races both start Putney Station opens. ease to Wimbledon. Precise date unknown from Putney, with both teams but records date an ordination in 1302. 1780 racing on the same day. Thames, and has evolved into one of the most A hurricane strikes the Putney area, damaging buildings and land from Lord Besborough’s desirable and celebrated areas of London. house at Roehampton, ending at Hammersmith where the church sustained considerable damage It is also the birthplace of some of history’s most 1647 The Putney debates, where officers and soldiers of ST.