Informgloucestershire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gloucestershire Local Nature Partnership

Gloucestershire Local Nature Partnership ‘Call for Evidence’ Response to Gloucestershire’s Local Industrial Strategy Page 1 of 54 Gloucestershire Local Nature Partnership Local Nature Partnerships (LNPs) were formed as part of the government’s 2011 white paper “The Natural Choice: Securing the value of nature”1. As part of a framework to strengthen local action to achieve the recovery of nature, LNPs were tasked to raise awareness about the vital services and benefits that a healthy natural environment brings for people, communities and the local economy. LNPs were to contribute to the green economy and complement Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), of which there is an expectation from government for LNPs and LEPs to form strong links that capture the value of nature. Here in Gloucestershire, the LNP is formed of over 30 organisations from public, private and third sector bodies from across the county, all working together as an informal partnership to recognise the importance of embedding nature's value in local decisions for the benefit of the nature, people and the economy. The GLNP Mission is to champion the essential role of Gloucestershire’s natural environment in sustaining a vibrant, healthy, prosperous economy and society. With a Vision of a healthy and valued natural environment, sustaining the economy and wellbeing of Gloucestershire. Our partnership provides a strong and innovative voice for the environment sector and is seen as a key partner in helping deliver the Gloucestershire County Council’s Strategy 2019-20222. We benefit from a solid working relationship with GFirst LEP, as well as all the District Councils. -

In 1968. the Report Consists of the Following Parts: L the Northgate Turnpike Roads 2 Early Administration and the Turnpike Trust

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1971 pages 1-58 [This edition was reprinted in 1987 by the Author in Hong Kong with corrections and revised pagination] THE NQRIH§AIE.IHBNBlKE N SPRY For more than one hundred and seventy years the road from the city of Gloucester to the top of Birdlip Hill, and the road which branched eastwards from it up Crickley Hill towards Oxford and later London, was maintained from the proceeds of the various turnpikes or toll gates along it. This report examines the history and administration of these roads from their earliest period to the demise of the Turnpike Trust in l87l and also details excavations across the road at Wotton undertaken in 1968. The report consists of the following Parts: l The Northgate Turnpike roads 2 Early administration and the Turnpike Trust 3 Tolls, exemptions and traffic 4 Road materials 5 Excavations at Wotton 1968 I Summary II The Excavations III Discussion References 1 IHE.NQBIH§AIE.BQADfi The road to Gloucester from Cirencester and the east is a section of the Roman road known as Ermine Street. The line of this road from Brockworth to Wotton has been considered to indicate a Severn crossing at Kingsholm one Km north of Gloucester, where, as late as the seventeenth century, a major branch of the river flowed slightly west of modern Kingsholm. The extent of early Roman archaeological material from Kingsholm makes it likely to have been a military site early in the Roman period. (l) Between Wotton Hill and Kingsholm this presumed line is lost; the road possibly passed through the grounds of Hillfield House and along the ridge, now marked by Denmark Road, towards the river. -

Air Quality Action Plan 2011

Environment Act 1995 Air Quality Action Plan 2011 Birdlip – Air Balloon Roundabout COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL Executive Summary Producing an Action Plan is a requirement of the Environment Act 1995. It follows the work carried out to assess the air quality in the area around the Air Balloon junction and the consideration of whether compliance with the air quality objectives, as set out in the Air Quality Regulations 2000 and Air Quality (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2002 have been achieved. The Air Quality in the area around the Air Balloon junction is not meeting the national air quality objectives for Nitrogen Dioxide pollution. |n developing the Action Plan various options that could impact on the area and the air quality within the Air Quality Management Area at Birdlip have been considered. In addition, the cost effectiveness of each action has been considered and the options have been ranked them according to effectiveness. This Action Plan was consulted on with residents and relevant organisations over the Summer of 2011, and the responses received have been reflected in the final version of the Action Plan. There are three properties of concern within the AQMA with permanent residents (or the potential for permanent residents). There are at least three residents in the two Air Balloon Cottages and at present there are no permanent residents in the Air Balloon Pub but there is potential for this to change in the future A Further Assessment carried out in 2010 included a source apportionment assessment and identified that within the AQMA nitrogen dioxide concentrations on both the A417 westbound and A417 southbound are substantially influenced by HGV vehicles. -

Implant Ceramic Centre

A449449 HerefordHereford A44A44 11 A438A438 LLedburyedbury BanburyBanbury A422A422 8 A429A429 A438A438 A46A46 A49A49 A449A449 9 A43A43 How to find A465 M50 ChippingChipping M5 A435A435 10 4 NortonNorton Ross-Ross- 10 CheltenhamCheltenham Implant & Ceramic Centre Ltd GloucesterGloucester A361A361 A44A44 on-wyeon-wye A40A40 11 AA4040 A436A436 9 A424A424 A40A40 11a A40A40 A34A34 A46A46 A417A417 A435A435 M40 A40A40 Cirencester A417 A40 12 A429A429 A40A40 Stroud (A46) The SOUTH WEST 8a Oxford (A40) Stroud A4042 13 MiserdenMiserden M5 TO A48A48 A38A38 OxfordOxford Bristol A449 StroudStroud A419A419 CirencesterCirencester A361A361 8 TEWKESBURY, 7 A417 TO 14 A419A419 The SOUTH WEST THE NORTH GLOUCESTER, Bristol London Cirencester A420A420 WALES (M5) M5 A419A419 A417 M48 A46A46 A433A433 A429A429 A 11A 22 21 4 SwindonSwindon 1 Newport 7 20 17 M4 16 A338A338 A34A34 Avonmouthuth 18a 19 17 15 Cirencester A417 18 18 Oxford (A40) 19 A346A346 5 Portishead ChippenhamChippenham 14 13 M5 M M4 12 BristolBristol A46A46 1a A4A4 MarlboroughMarlborough Junction 1 Cheltenham A4A4 A350A350 Stroud A4A4 Weston A37A37 AA346346 NewburyNewbury A4A4 A46 BRISTOLBRISTOL BathBath Super AIRPORTAIRPORT Mare Cirencester A 4 Stow-on-the-Wold A436 A436 TO 17 Oxford (A40) A417 A46 ANDOVERSFORD, A46 TO WINCHCOMBE, M5 TO Gloucester CHELTENHAM A40, OXFORD, M40 N BRISTOL A417 Leckhampton THE SOUTH TO 6 A 4 3 LECKHAMPTON, The MIDLANDS A46 Cirencester Cheltenham A417 CHELTENHAM Tewkesbury B Birdlip R O (B4070) C IR C 3 6 EN 4 Gloucester C K A R ES W Cirencester OAD TE O R R T A417 D A H B R 4 Y K 17 P A C S S W I AIRAIR 11A I N S BALLOONBALLOON PA Cirencester A417 (PH)(PH) 0 1 mile 2 mile Stroud 7 1 B4070 4 E R Approximate scale M I A N W AY Birdlip ROYALROYAL GEORGEGEORGE Key HOTELHOTEL Recomended route TO Cranham 1 BIRDLIPB I R D L I P Scenic Scout H.Q. -

Romanhurst, Birdlip Hill, Witcombe, Gloucestershire GL3 4SN

ROMANHURST WITCOMBE GLOUCESTERSHIRE Romanhurst, Birdlip Hill, Witcombe, Gloucestershire GL3 4SN A VERSATILE PERIOD FAMILY HOME WITH PANORAMIC VIEWS PLUS APPROXIMATELY 4.5 ACRES OF ANCIENT MEADOWS, IDEALLY PLACED FOR ACCESSING GLOUCESTER, CHELTENHAM AND THE M5 MOTORWAY Semi-detached with Entrance Porch, Kitchen/Dining/ Sitting Room, further Reception Room with kitchenette, ground floor Cloak/Shower Room, Utility area, 4 first floor Bedrooms and Family Bathroom. Self-contained Annexe with its own access with Entrance Hall, Sitting Room, Kitchen, Bedroom and Bathroom over. Garage with additional storage, ample parking, Summer House/Studio, extensive Garden merging with adjacent Meadows, circa 4.5 acres PRICE GUIDE £795,000 DESCRIPTION implies, the Romans were among the first to recognise the strategic importance of this Romanhurst offers a versatile home, perfect for an extended family. With 4.5 acres of location, making it the confluence of several Roman roads. An excellent road network grounds, the property would make an ideal smallholding and offers a wonderful still exists today, with easy access to the A417 linking Junction 11a of the M5 motorway exploration ground for children. Semi-detached, Romanhurst has classic views over (Cheltenham) with M4 Motorway Junction 15 (Swindon), or across to the A40 for Oxford Witcombe Valley. The Victorian element ensures there is plenty of natural light and its and London. Gloucester and Cheltenham are easily accessed for schools, shopping and rooms are well-proportioned. No more so than the spectacular hub at its centre which sport - premier division rugby and National Hunt racing. Birdlip has an excellent village forms the focal point of the house, with a lovely old staircase leading off. -

Gloucestershire Parish Map

Gloucestershire Parish Map MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT 1 Charlton Kings CP Cheltenham 91 Sevenhampton CP Cotswold 181 Frocester CP Stroud 2 Leckhampton CP Cheltenham 92 Sezincote CP Cotswold 182 Ham and Stone CP Stroud 3 Prestbury CP Cheltenham 93 Sherborne CP Cotswold 183 Hamfallow CP Stroud 4 Swindon CP Cheltenham 94 Shipton CP Cotswold 184 Hardwicke CP Stroud 5 Up Hatherley CP Cheltenham 95 Shipton Moyne CP Cotswold 185 Harescombe CP Stroud 6 Adlestrop CP Cotswold 96 Siddington CP Cotswold 186 Haresfield CP Stroud 7 Aldsworth CP Cotswold 97 Somerford Keynes CP Cotswold 187 Hillesley and Tresham CP Stroud 112 75 8 Ampney Crucis CP Cotswold 98 South Cerney CP Cotswold 188 Hinton CP Stroud 9 Ampney St. Mary CP Cotswold 99 Southrop CP Cotswold 189 Horsley CP Stroud 10 Ampney St. Peter CP Cotswold 100 Stow-on-the-Wold CP Cotswold 190 King's Stanley CP Stroud 13 11 Andoversford CP Cotswold 101 Swell CP Cotswold 191 Kingswood CP Stroud 12 Ashley CP Cotswold 102 Syde CP Cotswold 192 Leonard Stanley CP Stroud 13 Aston Subedge CP Cotswold 103 Temple Guiting CP Cotswold 193 Longney and Epney CP Stroud 89 111 53 14 Avening CP Cotswold 104 Tetbury CP Cotswold 194 Minchinhampton CP Stroud 116 15 Bagendon CP Cotswold 105 Tetbury Upton CP Cotswold 195 Miserden CP Stroud 16 Barnsley CP Cotswold 106 Todenham CP Cotswold 196 Moreton Valence CP Stroud 17 Barrington CP Cotswold 107 Turkdean CP Cotswold 197 Nailsworth CP Stroud 31 18 Batsford CP Cotswold 108 Upper Rissington CP Cotswold 198 North Nibley CP Stroud 19 Baunton -

Ridge Cottage £420,000

Ridge Cottage Stroud Road, Birdlip GL4 8JN A wonderfully unique home located on the edge of this desirable village affording stunning far-reaching views. This charming detached house is constructed of Cotswold stone and enjoys other character features such as stone mullion leaded windows, exposed timbers, flagstone floors and a lovely red brick fire place. Guide Price £420,000 The main living room benefits from a dual aspect with French doors opening out in to the garden and those amazing views. A mezzanine floor not only adds further character but a useful space creating the ideal study or bedroom. The entrance hallway flows into the fitted kitchen. Another light, open space with a range of oak fronted wall and base units, integrated fridge, electric oven and hob. There is a double bedroom and bathroom of three-piece white suite with an electric shower over the bath. The rear garden is paved with mature planted borders Ground Floor creating the perfect place to sit, relax and enjoy the view. 44.2 SQ.M (475 SQ.FT.) A truly individual home, in a privileged setting enjoying a breath-taking vista and with the benefit of driveway parking for 2/3 cars to the front surrounded by a Cotswold stone wall. First Floor: 20.9 SQ.M (225 SQ.FT.) PROPERTY INFORMATION Services: Mains electricity, water and drainage are connected to the property. Electric storage heating. Total Approx Floor Area: Gigaclear fast fibre broadband. 65.1 SQ.M (701 SQ.FT.) EPC E (50). Outgoings: Council Tax Band ‘D’ 2021/22 charges £1,822.92. -

Througham Slad Manor

THROUGHAM SLAD MANOR BISLEY, GLOUCESTERSHIRE Gloucestershire Cotswolds u Througham Slad Manor stands in the most delightful secluded position in the heart of the Cotswolds with superb views over the surrounding wooded valleys. u The property stands in a peaceful setting at the end of a No Through Road, however is conveniently placed for access to Cirencester, Cheltenham and Stroud which all provide extensive shopping and recreational facilities. u Communications are good with easy access to the M5 and M4 about 11 and 27 miles distant respectively. A regular train service runs from Kemble Station (about 10 miles south) to London Paddington taking approximately 85 minutes. u The house is well located for social activities, with the Cotswold, the VWH and The Duke of Beaufort’s hunts nearby; golf at the nearby Cirencester club and other courses at Naunton Downs, Cheltenham, Burford and Minchinhampton. Racing at Cheltenham and Bath; polo at Cirencester Park and Westonbirt. u Believed to date from the mid 16th century with 18th century additions, the manor was altered in the 1930’s by the renowned architect Norman Jewson for the Cadbury family. Of Cotswold stone construction, under a stone tile roof, the manor house has some wonderful period features including mullioned windows, a fine Norman Jewson staircase and inglenook fireplaces. u The house has been improved in recent years to provide fabulous family accommodation. The Barn, once a recording studio, has been converted to an excellent guest cottage, and a new swimming pool installed with terracing and superb views over the valley below. Ground Floor u Reception hall with Cotswold stone flagged floor and u Kitchen/breakfast room, a wonderful family kitchen with oak u Master bedroom suite, a beautiful light bedroom open to restored elm panelling. -

Stratigraphical Framework for the Middle Jurassic Strata of Great

Stratigraphical framework for the Middle Jurassic strata of Great Britain and the adjoining continental shelf Geology and Landscape Programme Research Report RR/11/06 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/11/06 The National Grid and other Stratigraphical framework for the Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database rights 2012. Ordnance Survey Licence Middle Jurassic strata of Great No. 100021290 Britain and the adjoining Key words Geology, stratigraphy, lithostratigraphy, Inferior Oolite continental shelf Group, Great Oolite Group, Ravenscar Group, Great Estuarine Group, Sutherland Group, Ancholme Group, Jurassic. A J M Barron, G K Lott, J B Riding Front cover Hilltop Quarry, Leckhampton Hill, Cheltenham, Glos.: the Birdlip Limestone Formation overlain by the Aston Limestone Formation. (P775213, A J M Barron) Bibliographical reference BARRON, A J M, LOTT, G K, AND RIDING, J B. 2012. Stratigraphical framework for the Middle Jurassic strata of Great Britain and the adjoining continental shelf. British Geological Survey Research Report, RR/11/06. 187pp. ISBN 978 0 85272 695 2 Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided -

Beverley Cottage Birdlip

COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL Dated 25th February 2020 COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL TREE PRESERVATION ORDER NO 20/00002 Beverley Cottage, Birdlip Town and Country Planning Act 1990 The Town and Country Planning (Tree Preservation)(England) Regulations 2012 TREE PRESERVATION ORDER relating to Beverley Cottage, Birdlip Trin ity Road, Cirencester, Gloucestershire, GL7 IPX Tel: 01285 623000 Fax: 01285 623900 www.cotswold.gov.uk TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 THE TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (TREE PRESERVATION)(ENGLAND) REGULATIONS 2012 COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL TREE PRESERVATION ORDER NO 20/00002 Beverley Cottage, Birdlip 2020 The Cotswold District Council, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by section 198 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 make the following Order- Citation 1. This Order may be cited as TPO Number 20/00002, Beverley Cottage, Birdlip 2020 Interpretation 2. (1) In this Order "the authority" means the Cotswold District Council. (2) In this Order any reference to a numbered section is a reference to the section so numbered in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and any reference to a numbered regulation is a reference to the regulation so numbered in the Town and Country Planning (Tree Preservation)(England) Regulations 2012. Effect 3. (1) Subject to article 4, this Order takes effect provisionally on the date on which it is made. (2) Without prejudice to subsection (7) of section 198 (power to make tree preservation orders) or subsection (1) of section 200 (tree preservation orders: Forestry Commissioners) and, subject to the exceptions in regulation 14, no person shall- (a) cut down, top, lop, uproot, wilfully damage, or wilfully destroy; or (b) cause or permit the cutting down, topping, lopping, wilful damage or wilful destruction of, · any tree specified in the Schedule to this Order except with the written consent of the authority in accordance with regulations 16 and 17, or of the Secretary of State in accordance with regulation 23, and, where such consent is given subject to conditions, in accordance with those conditions. -

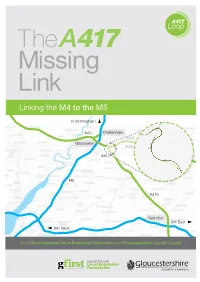

Linking the M4 to the M5

Linking the M4 to the M5 To Birmingham A40 Cheltenham A436 Gloucester A436 To Oxford A40 A417 M5 A419 Swindon M4 East M4 West From and BristolGloucestershire Local Enterprise Partnership Gloucestershire County Council A417 Loop | Connecting the M4 to M5 3 CONTENTS FOREWORD For more than 20 years, Gloucestershire and surrounding counties have been looking for a solution to the ‘Missing Link’ on the A417.The 5km stretch of road, near Nettleton Bottom, is the only single carriageway along the strategic 50km route between the 3 Foreword / Pledge M4 and M5. The route is a key link between the West Midlands and London and is used daily by more than 34,000 The Problem 4 vehicles. The ‘Missing Link’ is often very heavily congested and there are frequent accidents, affecting people across Gloucestershire and further afield. What We Want / The Solution 6 Gloucestershire County Council has consistently campaigned for something to be done to address the problem, which is seriously affecting our local economy and, more importantly, people’s safety. Recent 8 The Economic Impact fatalities on the ‘Missing Link’ are a tragic reminder of why we need to act now. The A417 loop scheme, the only workable solution to this problem, is not currently included in any 10 Connectivity Research in Gloucestershire 2013 national infrastructure delivery programme despite more than 20 years of investigations. We’ve worked with the Highways Agency (HA) which has invested its time and money into finding the 11 Case Study right solution – now we need that solution to be implemented. Gloucestershire is firmly behind the A417 Loop scheme. -

A417 Missing Link

A417 Missing Link Welcome We are seeking your views on our proposed route options for a solution to the A417 Missing Link. The information we receive during this consultation will help us develop a preferred route. We would encourage you to read the information on display today, take a copy of our consultation booklet and provide your thoughts by completing a feedback form. You can either complete a feedback form and leave it with us today, post it to us or it can be found online. Address: FREEPOST A417 MISSING LINK Website: www.highways.gov.uk/a417-missing-link Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0300 123 5000 Your feedback is important to us in shaping a solution for this section of the A417. We will consider all feedback we receive and use it to help us develop our proposals further. Please send us your feedback form by the end of 29 March 2018. Highways England – Creative BSR18_0036 A417 Missing Link About the A417 Together, the A417 and A419 through the Cotswolds make up one of the south west’s most important road corridors, helping people get to work and school and visit family and friends. But there’s a problem. While most of the route is dual carriageway, there’s one section that isn’t. Known as the ‘Missing Link’, this 3-mile stretch of single carriageway on the A417 between the Brockworth bypass and Cowley roundabout restricts the flow of traffic, causing congestion and pollution. Congestion can be so unpredictable that some motorists rat run along local roads, affecting the communities along these routes.