Colorado State Trust Land Access Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOCO Grants Awarded in Fiscal Year 2018 by County County Grant Type

GOCO Grants Awarded in Fiscal Year 2018 by County County Grant Type Project Sponsor Project Title Grant Amount Adams Inspire City of Westminster Westy Power/Poder $1,423,297.00 Adams Restoration City of Thornton Big Dry Creek Pilot Project Floodplain Restoration $100,000.00 Adams Youth Corps City of Brighton Raptor Flyway Invasive Species Removal Project $36,000.00 City of Thornton/Adams County Big Dry Creek Adams Youth Corps City of Thornton $35,600.00 Master Plan Russian Olive Removal Alamosa Inspire City of Alamosa Recreation Inspires Opportunity (RIO) $501,399.00 Local Alamosa City of Alamosa Montana Azul Park Phase One $347,794.00 Government Arapahoe Inspire City of Sheridan Sheridan Inspire $1,703,842.00 Local Arapahoe City of Aurora Side Creek Playground Rejuvenation $90,007.00 Government Arapahoe Planning City of Aurora Plains Conservation Center Strategic Master Plan $75,000.00 South Suburban Park and Rec Arapahoe Youth Corps South Platte Park Weed Tree Removal $18,000.00 District Bent Open Space Southern Plains Land Trust Heartland Ranch Preserve Expansion $310,700.00 Bent Restoration Southern Plains Land Trust Prairie Stream Restoration $41,262.00 Local Boulder Town of Nederland Chipeta Park Enhanced Accessibility $31,727.58 Government Local Boulder Town of Jamestown Cal-Wood Educational Greenhouse $25,443.00 Government Eldorado Canyon State Park Entrance Station Boulder Parks Colorado State Parks $650,000.00 Relocation Boulder Parks Colorado State Parks Boulder County Feasibility Study - Hwy 36 $400,000.00 City of Louisville South Boulder Road Ped. & Boulder Planning City of Louisville $75,000.00 Bicycle Connectivity Feasibility Study and Plan Local Chaffee Town of Buena Vista Buena Vista Community Baseball Field $350,000.00 Government Chaffee Open Space Central Colorado Conservancy Elk Meadows Conservation Easement $46,200.00 Chaffee Parks Colorado State Parks Envision Recreation in Balance $99,367.00 Mt. -

Code of Colorado Regulations 1 J

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Colorado Parks and Wildlife CHAPTER P-7 - PASSES, PERMITS AND REGISTRATIONS 2 CCR 405-7 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS AND FEES RELATING TO PASSES, PERMITS AND REGISTRATIONS VEHICLE PASSES #700 - VEHICLE PASS 1. Except as otherwise provided in these regulations or by Colorado Revised Statutes, no motor vehicle shall be brought onto any Parks and Outdoor Recreation lands unless a valid pass issued by the Division is properly attached. Passes that are designed to be affixed to the windshield shall be attached to the extreme lower right-hand corner of the vehicle’s windshield in a position so that the pass may be observed and identified. For an annual vehicle pass, including an aspen leaf annual pass to be properly attached to a windshield it must be permanently affixed. Any vehicle without a windshield shall be treated as a special case, but evidence of a pass shall be required. Other types of passes, such as hang tag passes, shall be continuously displayed in the motor vehicle in the manner described on the pass while the motor vehicle is operated or parked on Division properties. 2. No vehicle pass shall be required for: a. Any snowmobile as defined in section 33-14-101, C.R.S.; b. Any off-highway vehicle as defined in section 33-14.5-101(3), C.R.S.; c. Any government-owned vehicle, emergency vehicle, or law enforcement vehicle on official business; d. Any commercial delivery vehicle delivering goods to the park or a park concessionaire when the goods are directly related to the operation of the park or concession; e. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

CCLOA Directory 2021

2 0 2 1 Colorado’s Most Comprehensive Campground Guide View Complete Details on CampColorado.com Welcome to Colorado! Turn to CampColorado.com as your first planning resource. We’re delighted to assist as you plan your Colorado camping trips. Camp Colorado All Year Wildfires Table of Contents Go ahead! Take in the spring, autumn and winter festivals, Obey the local-most fire restrictions! That might be the Travel Resources & Essential Information ..................................................... 2 the less crowded trails, and some snowy adventures like campground office. On public land, it’s usually decided by snowshoeing, snowmobiling, cross country skiing, and the county or city. Camp Colorado Campgrounds, RV Parks, & Other Rental Lodging .............. 4 even downhill skiing. Colorado Map ................................................................................................. 6 Wildfires can occur and spread quickly. Be alert! Have an MAP Colorado State Parks, Care for Colorado ...................................................... 8 Many Colorado campgrounds are open all year, with escape plan. Page 6 Federal Campgrounds, National Parks, Monuments and Trails ................... 10 perhaps limited services yet still catering to the needs of those who travel in the off-seasons. Campfires aren’t necessarily a given in Colorado. Dry Other Campgrounds ...................................................................................... 10 conditions and strong winds can lead to burn bans. These Wildfire Awareness, Leave No -

Sanitary Disposals Alabama Through Arkansas

SANITARY DispOSAls Alabama through Arkansas Boniface Chevron Kanaitze Chevron Alaska State Parks Fool Hollow State Park ALABAMA 2801 Boniface Pkwy., Mile 13, Kenai Spur Road, Ninilchik Mile 187.3, (928) 537-3680 I-65 Welcome Center Anchorage Kenai Sterling Hwy. 1500 N. Fool Hollow Lake Road, Show Low. 1 mi. S of Ardmore on I-65 at Centennial Park Schillings Texaco Service Tundra Lodge milepost 364 $6 fee if not staying 8300 Glenn Hwy., Anchorage Willow & Kenai, Kenai Mile 1315, Alaska Hwy., Tok at campground Northbound Rest Area Fountain Chevron Bailey Power Station City Sewage Treatment N of Asheville on I-59 at 3608 Minnesota Dr., Manhole — Tongass Ave. Plant at Old Town Lyman Lake State Park milepost 165 11 mi. S of St. Johns; Anchorage near Cariana Creek, Ketchikan Valdez 1 mi. E of U.S. 666 Southbound Rest Area Garrett’s Tesoro Westside Chevron Ed Church S of Asheville on I-59 Catalina State Park 2811 Seward Hwy., 2425 Tongass Ave., Ketchikan Mile 105.5, Richardson Hwy., 12 mi. N of on U.S. 89 at milepost 168 Anchorage Valdez Tucson Charlie Brown’s Chevron Northbound Rest Area Alamo Lake State Park Indian Hills Chevron Glenn Hwy. & Evergreen Ave., Standard Oil Station 38 mi. N of & U.S. 60 S of Auburn on I-85 6470 DeBarr Rd., Anchorage Palmer Egan & Meals, Valdez Wenden at milepost 43 Burro Creek Mike’s Chevron Palmer’s City Campground Front St. at Case Ave. (Bureau of Land Management) Southbound Rest Area 832 E. Sixth Ave., Anchorage S. Denali St., Palmer Wrangell S of Auburn on I-85 57 mi. -

Colorado Wildfire Mitigation Projects

Programmatic Environmental Assessment Colorado Wildfire Mitigation Projects May 2014 Federal Emergency Management Agency Department of Homeland Security Region VIII Denver, Colorado 80225 Table of Contents Programmatic Environmental Assessment Colorado Wildfire Mitigation Projects Acronyms and Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................iii Section One Introduction ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background ..........................................................................................................................4 1.2 Purpose and Need ................................................................................................................ 5 Section Two Alternatives…………………………………………………………………..…6 2.1 Alternatives Not Retained………………………………………………………………... 6 2.2 Alternatives Considered……………………………………………………………….6 2.2.1 Alternative 1 – No Action ………………………………………………………...7 2.2.2 Alternative 2 – Vegetation Management……………………………………..........7 2.2.3 Alternative 3 – Structural Protection through Ignition-Resistant Construction…..9 Section Three Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences…………….....9 3.1 Physical Resources ....................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Affected Environment ................................................................................... 9 3.1.2 Environmental Consequences .................................................................... -

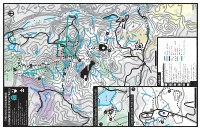

THE C OOLIDGE R ANGE SUMMER RECREATION TR AILS Legend Giff

VERMONT THE COOLIDGE RANGE Long Trail North 100 Tucker Johnson 2000 Thundering North SUMMER RECREATION TRAILS Brook Rd Willard Gap Giord Woods Kent Pond Coolidge State Forest State Park Giord Woods State Park 3 Coolidge State Park Deer Leap Mtn Plymsbury Wildlife Management Area 2782’ Rd River Green Mountain National Forest Deer Leap Old Maine Jct. Appalachain Trail Corridor Overlook Rutland City Forest 2000 k West Hill Rd o o Forest Legacy Public Access Easments r B t n e 4 K 4 Killington Rd Pico Pond VERMONT 3000 100 3 Wheelerville Rd 4 3800 Churchill Scott Pico Camp/ spring Pico Peak 3957’ Little Pico Gre o k 3110’ at R oaring Bro Ottauquechee River Rams Head Mtn 3618’ East Roaring Brook Rd Brewers Corners Shagback Mtn Brewers Brook 7 Snowdon Peak 2688’ 3592’ 1800 Skye Peak 2000 3816’ 1600 2200 Cooper Lodge Ed dy 2400 Bro ok 2600 4 Killington Peak ok 2800 s ro 4235’ Fall B 3000 3 Bear Mtn Wheelerville Rd Ottauquechee 3262’ River Notch Rd Mendon Peak 3800 3840’ 3600 Little Killington Peak 3939’ 3200 Ma 3000 dden Brook Reservoir Brook Giord Woods State Park Trails VERMONT North VERMONT Shrewsbury Peak 100 100 3710’ Smith Peak ok Robinson Hill ro 3205’ B t n 2747’ e Shrewsbury Peak rg a S 6 Kent Pond 3200 9 Gov. Clement 3000 1 2800 5 2600 Woodard Jockey Hill Reservoir 2400 2640’ Russell Stone Hut Hill CCC Road 1800 Ingalls Hill Russell Hill 1600 2654’ 2545’ 2000 Tinker Brook 8 Black Pond ko Thundering T ro Brook Rd i n B 2200 k e r 1000 500 0 1000 2000 4 feet Tin Shanty Rd Shanty Tin Black River North Coolidge State Park Trails Upper Cold River Rd Burnt Mtn 2803’ VERMONT 1200 100A 2000 Cold River Rd 2 Northam Rd Round Top Mtn Rd 1400 VERMONT North Shrewsbury Old Plymouth Rd 100 k to Coolidge State Park oo Br ing via Rt 100A 3 mi. -

Your Guide to Colorado's 41 State Parks

COLORADO PARKS & WILDLIFE Your Guide to Colorado’s 41 State Parks 2019-2020 Edition cpw.state.co.us CAMPING RESERVATIONS • 1-800-244-5613 • cpw.state.co.us i Welcome to Your State Parks! Plan Your Visit Wherever you go in Colorado, there’s Colorado’s state parks are open every day of the year, weather Cheyenne Mountain a state park waiting to welcome State Park permitting. Day-use areas are generally open from 5 a.m. to you. Mountains or prairies, rivers or 10 p.m., and some parks may have closed gates after hours. forests, out in the country or next to Campgrounds are open 24 hours a day. Contact individual parks the city… Colorado’s 41 state parks are for specific hours of operation and office hours. Check our website as diverse as the state itself, and they for seasonal or maintenance closures: cpw.state.co.us offer something for everyone. Take a hair-raising whitewater river trip, or Entrance Passes kick back in a lawn chair and watch All Colorado state parks charge an entrance fee. Cost of a daily pass the sunset. Enjoy a family picnic, cast may vary by park ($8–$9). They cover all occupants of a vehicle and a line in the water, take a hike, ride a are valid until noon the day after purchase. Some parks may charge horse, try snowshoeing or discover a per-person fee for cyclists and walk-ins ($4). Fees are used to help geocaching. From Eastern Plains pay operating costs. Cherry Creek State Park charges an additional parks at 3,800 feet to high-mountain fee for the Cherry Creek Basin Water Quality Authority. -

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 2 CCR 405-1 Colorado Parks and Wildlife

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Colorado Parks and Wildlife CHAPTER P-1 - PARKS AND OUTDOOR RECREATION LANDS 2 CCR 405-1 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL PARKS AND OUTDOOR RECREATION LANDS AND WATERS # 100 - PARKS AND OUTDOOR RECREATION LANDS A. Definitions 1. “Parks and Outdoor Recreation Lands” shall mean, whenever used throughout these regulations, all parks and outdoor recreation lands and waters under the administration and jurisdiction of the Division of Parks and Wildlife. 2. “Wearable Personal Flotation Device” shall mean a U.S. Coast Guard approved personal flotation device that is intended to be worn or otherwise attached to the body. A personal flotation device labeled or marked as Type I, II, III, or V (with Type I, II, or III performance) is considered a wearable personal flotation device as set forth in the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 33, Parts 175 and 181(2014). B. When these regulations provide that an activity is prohibited except as posted or permitted as posted, the Division will control these activities by posting signs identifying the prohibited or authorized activities, specifying the affected area and the basis for the posting. The Division will apply the following criteria in determining if an activity will be restricted or authorized pursuant to posting: 1. Public safety or welfare. 2. Potential impacts to wildlife, parks or outdoor recreation resources. 3. Remediation of prior impacts to wildlife, parks or outdoor recreation resources. 4. Whether the activity will unreasonably interfere with existing authorized activities or third party agreements. -

The Cache La Poudre River: from Snow to Flow

The Cache la Poudre River: From Snow to Flow The Cache la Poudre River is located in northern Colorado. It spans nearly 130 miles in length and drops over 6,100 feet (1860 meters) in elevation. The river is a popular destination for rafting and fishing, two activities that rely on continuing flow of water. But where is this water coming from and where does it go? Let's find out. Activity Introduction This activity uses a series of interactive web maps, embedded videos, and printable worksheets to help you learn about watershed hydrology. Want to test your watershed knowledge? Click here to take a pre-test. (We'll compare your answers with a post-test later to see how much you've learned!) Note, there are two types of links throughout this story: - Links in green will open a new tab and direct you to a different site - Links in blue are locations highlighted on our map, click on them to explore the map content Teachers These online activities support an in-depth curriculum module for middle school students and beyond. This module can be used for education on hydrologic processes within the Cache la Poudre Watershed, in Northern Colorado. To access additional resources, visit our research website. There you can find lesson plans, student worksheets, and additional materials. Vocabulary Hydrology - the science involving the presence, distribution, movement, and properties of water on land Hydrologic Cycle - the circulation of water as it moves between the land, oceans, and atmosphere. Main components include: precipitation, evaporation, soil water, groundwater, and streamflow. -

State Forest State Park Management Plan

Table of Contents Management Planning Team ................................................................................................... 5 Partners and Stakeholders ...................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 7 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 9 Park Description ..................................................................................................................... 9 Purpose of the Plan ................................................................................................................ 9 Relationship to the CPW Strategic Plan .............................................................................10 Park Goals ..........................................................................................................................11 Previous Planning Efforts ...................................................................................................12 Public Input Process ...........................................................................................................12 Influences on Management ................................................................................................13 Management Considerations ..............................................................................................13 -

Parks and Outdoor Recreation Chapter 1

AS APPROVED - 11/19/2020 FINAL REGULATIONS - CHAPTER P-1 - PARKS AND OUTDOOR RECREATION LANDS ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS APPLICABLE TO ALL PARKS AND OUTDOOR RECREATION LANDS AND WATERS # 100 - PARKS AND OUTDOOR RECREATION LANDS PARK-SPECIFIC RESTRICTIONS D. In addition to the general land and water regulations, the following restrictions shall also apply: 1. Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area a. Except in established campgrounds where toilet facilities are provided, all overnight campers must provide and use a portable toilet device capable of carrying human waste out of the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area. Contents of the portable toilet must be emptied in compliance with law and may not be deposited within the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area, unless at a facility specifically designated by the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area. b. Building or tending fires is allowed pursuant to regulation # 100b.7., except at the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area fire containers must have at least a two inch rigid side. Fire containers must be elevated up off the ground. c. Swimming is permitted in the Arkansas River from the confluence of the East Fork/Lake Fork of the Arkansas within the boundaries of the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area. All persons swimming within designated whitewater parks and all persons under the age of 13 swimming anywhere in the Arkansas River within the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area must wear a properly fitting U.S. Coast Guard approved wearable personal flotation device. d. No motorboats shall be permitted on the Arkansas River from the confluence of the East Fork/Lake Fork of the Arkansas to the west end of Pueblo Reservoir.