Fernando M. Reimers Editor How Governments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROMOTING MATHEMATICAL THINKING in FINNISH MATHEMATICS EDUCATION Heidi Krzywacki, Leila Pehkonen & Anu Laine University of Helsinki

1 PROMOTING MATHEMATICAL THINKING IN FINNISH MATHEMATICS EDUCATION Heidi Krzywacki, Leila Pehkonen & Anu Laine University of Helsinki Abstract In this article, we outline some of the main characteristics of the mathematics education in the Finnish educational context. In Finland, at both primary and secondary school levels teachers are educated to be autonomous and reflective academic experts. This policy means there is a strong emphasis on teachers’ independence and autonomous responsibility and it also has many consequences for teaching mathematics. We start by discussing the main features of Finnish mathematics education through the outline stated in the National Core Curriculum and reflecting on the features of teacher education, which prepares academic, pedagogically thinking teachers for school work. In Finland, mathematics education is highly dependent on teachers and their understanding of teaching and learning mathematics. Secondly, we elaborate the practical and environmental aspects influencing schooling and the way mathematics is taught in Finnish comprehensive schools. The central aspects characterising Finnish mathematics education, such as the distribution of lesson hours, the availability of pedagogically well-structured learning materials and the principles of school assessment, are discussed. To conclude, Finnish teachers responsible for teaching mathematics play a significant role in maintaining and developing the quality of school mathematics education. Keywords: mathematics education, comprehensive school, curriculum, teacher education 1 Introduction In Finland, basic education in mathematics is carried out by primary school teachers, responsible for the first six years of schooling, i.e., grades 1-6 when pupils are 7 to 12 years old, and by specialised subject teachers, who teach mathematics at secondary school level in grades 7-9 when pupils are 13 to 16 years old. -

Nuno Crato Paolo Paruolo Editors How Access to Microdata

Nuno Crato Paolo Paruolo Editors Data-Driven Policy Impact Evaluation How Access to Microdata is Transforming Policy Design Data-Driven Policy Impact Evaluation Nuno Crato • Paolo Paruolo Editors Data-Driven Policy Impact Evaluation How Access to Microdata is Transforming Policy Design Editors Nuno Crato Paolo Paruolo University of Lisbon Joint Research Centre Lisbon, Portugal Ispra, Italy ISBN 978-3-319-78460-1 ISBN 978-3-319-78461-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78461-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018954896 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Inter- national License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Weekend Trips

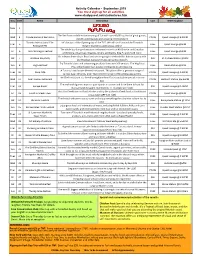

Activity Calendar - September 2019 You must sign up for all activities www.studyquest.net/studentarea.htm Day Date Name Description Cost Meeting place Mon 2 The Rec Room redefines the meaning of fun with over 40,000 sq. feet of great games, Wed 4 Arcade Games at Rec Room PYOW Quest Lounge @ 4:00PM mouth-watering eats and amazing entertainment Toronto International Film Let’s be part of the Opening day of the TIFF. We will stroll around the Toronto's Thur 5 FREE Quest Lounge @5PM Festival (TIFF) theatre district to spot famous actors! The whole day live performances welcomed more than 40 Chinese and Canadian Fri 6 Toronto Dragon Festival FREE Quest Lounge @3PM performing arts groups. Dragons, drums, acrobatics, King Fu and much more. It's independence day in Brazil and we are going to celebrate this date in a party with Sat 7 Brazilian Day Party $20 St Andrew Station @9PM Live Brazilian Carnaval drums and samba dancers Try Toronto’s best and unique veg products from over 160 vendors. The Veg Food Sun 8 Veg Food Fest FREE Union Station @1PM Fest is North America’s largest celebration of all things veg. A Toronto's washroom-themed restaurant. This place offers a generous range of Tues 10 Poop Café PYOW Quest Lounge @ 4:00PM various Asian desserts, from Thai rolled ice cream to Hong Kong egg waffles. Her Chef restaurant is a friendly neighbourhood fast-casual place specialize in rice Wed 11 Asian Fusion restaurant PYOW Bathurst Station @5:45PM box. The real-world games imprison participants in a room and force them to hunt for Thur 12 Escape Room $40 Quest Lounge @4:40PM clues around the game environment. -

Rules of Study at the University of Lodz

RULES OF STUDY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF LODZ Approved by the Resolution of the Senate of the UL no. 449 of 14 June 2019. Contents: I. GENERAL PROVISIONS [§1-§8] II. STUDENT’S RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS. AWARDS AND DISTINCTIONS [§9-§19] III. TAKING UP STUDIES [§20-§28] IV. ORGANIZATION OF STUDIES [§29-§34] V. PRINCIPLES OF THE ECTS SYSTEM [§35-§37] VI. COMPLETION OF A SEMESTER/ ACADEMIC YEAR [§38-§47] VII. SPECIFIC PROVISIONS ON COURSES AND PROGRAMMES OUTSIDE THE MAIN FIELD OF STUDY AND AT OTHER UNIVERSITIES [§48-§49] VIII. LEAVES OF ABSENCE FROM STUDY [§50-§51] IX. DIPLOMA THESIS (MASTER’S, AND BACHELOR’S, INCLUDING BACHELOR OF ENGINEERING) [§52-§55] X. DIPLOMA EXAM (MASTER’S, AND BACHELOR’S, INCLUDING BACHELOR OF ENGINEERING). COMPLETION OF STUDIES. [§56-§59] XI. FINAL PROVISIONS [§60-§63] I. GENERAL PROVISIONS §1 1. Studies at the University of Lodz are organized pursuant to binding provisions, and in particular: − the Act on Higher Education and Science of 20 July 2018 (Polish Official Journal, Year 2018, item 1668 as amended), hereinafter referred to as „the Act”; − Statutes of the University of Lodz, hereinafter referred to as „the Statutes”; − the present Rules of Study at the University of Lodz, hereinafter referred to as „the Rules”. 2. The Rules apply to full-time (standard daytime) and extramural (evening, weekend) studies, whether first-cycle, second-cycle, or uniform (direct) Master's degree programmes, held at the University of Lodz. §2 1. The following terms used in the Rules shall have the following meaning: 1)Faculty Council – -

Fall 2011 Gazette

GAZETTE A Publication for EurAupair Program Participants and Friends Around the World! Fall 2011 • Volume 50 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Thanksgiving Dinner • Surfing in the Atlantic Ocean • EurAupair Cultural Events in February • Halloween is Fun! Crowned Miss Brazilian By EurAupair Au Pair Céline Dietrich from France • Day 2011 Céline Dietrich from France, the atmosphere and the kindness of and More! EurAupair au pair with the Bozniak/ the people with whom I spend this • Stronach family of Washington, DC, beautiful day. I took it as a good is a big fan of American Thanksgiving sign for the year that I will spend celebrations: with them and I was right - I had a “My name is Céline, I am French beautiful year. About Us... and I celebrate this month my first Because I had such a great day, EurAupair Intercultural Child Care year in the United States. I am living when in February my 25th birthday Programs is a non-profit, public benefit organization designated by the U.S. with a wonderful host family in came, I asked my host family to have Department of State to conduct the Washington, D.C. I extended my a birthday like Thanksgiving dinner Au Pair cultural exchange program experience, so I will stay six more with the turkey, the macaroni and under the Fulbright Hays Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act months here with them. Maybe it’s cheese, and all the other typical side of 1961 and is intended “to promote because of the color of fall that I dishes. My family from France was mutual understanding between the people of the United States and other am thinking about it, but my best visiting me, so it was the occasion countries by means of educational and memory here as an au pair was for them to try the famous dish and cultural exchanges”. -

The Reform and Modernization of Vocational Education and Training in China

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hao, Yan Working Paper The reform and modernization of vocational education and training in China WZB Discussion Paper, No. SP III 2012-304 Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Hao, Yan (2012) : The reform and modernization of vocational education and training in China, WZB Discussion Paper, No. SP III 2012-304, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/57097 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons -

Sept 27 @ 7:30 PM the Beacon Theatre P. 7

NEW YORK | SEPTEMBER 1 2017 | BRAZILIAN MUSIC FOUNDATION | ASUOS | EDITION#3 SEU JORGE Sept 27 @ 7:30 PM The Beacon Theatre P. 7 A TRIBUTE TO DAVID BOWIE EDITOR’S NOTE Dear friends, On September 7th we will be celebrating 195 years of Brazilian freedom, Independence Day, with lots of fanfare and excitement. “Brazil’s Independence was officially announced on the 7th of September 1822 from the hands of the Portuguese. Since then it has been a country. For ages Brazil has represented the great escape to a prehistoric, tropical heaven, igniting the Western imagination like no other South American country. Brazil had its unique attributes including having had a reigning monarch and an empire that boasts of a relatively bloodless independence from Portugal. Brazilians did not have to fight tooth and nail nor did they create any type revolt. The King himself declared in the Grito do Ipiranga, "By my blood, by my honor, and by God: I will make Brazil free" with the motto "Independence or Death!" Every year, thousands get together in a mad passion to proudly celebrate Brazilian Independence Day. A country of mythic proportions, people gather in the streets celebrating with banners, balloons and streamers. For those that do not know anything about Brazilian culture, here is an opportunity to go to one of the events, get in the green and yellow mood, and see the richness of Brazilian art and hear the variety of sounds, rhythms and styles that exist in our repertoire. Furthermore, I hope you just enjoy the magazine in general and support Brazilian Music Foundation’s mission, which is to promote, educate and advance Brazilian Music in the Americas. -

5. Education・ Vocational Training Preliminary Study for Iraq Reconstruction Projects in Hashemite Kingdome of Jordan Final Report

5. Education・ Vocational Training Preliminary Study for Iraq Reconstruction Projects in Hashemite Kingdome of Jordan Final Report 5 Education and Vocational Training 5.1 Outline of Education and Vocational Training in Iraq The population in Iraq is estimated at 2.6 million with annual population growth rate of approximately 2.8%. The education system in Iraq showed high performance rate until the early 1980s and it achieved nearly universal primary enrollment in 1980. Thereafter, for more than two decades, the enrollment rate went into a steady decline and the attendance went down at an alarming rate. Out of nearly 15,000 existing school buildings, 80% now require significant restoration. More than 1,000 schools need to be demolished and completely reconstructed. Another 4,600 require major repair based on information from the Ministry of Education. Table 5.1.1 No. of Students by Level of School (excluding higher education) Level of Education No. of Source Students Kindergarten 53,499 MOE and UNICEF Primary school 4,280,602 MOE and UNICEF Secondary education (Intermediate and Preparatory) 1,454,775 MOE, UNICEF, UNESCO and USAID Vocational school 62,841 MOE and UNICEF Teacher training school 66,139 MOE and UNICEF Table 5.1.2 No. of Students by Sex by Level of Education (excluding higher education) Level of Education Sex No. of Students Source Female 26,068(48.73%) MOE and UNICEF Kindergarten Male 27,431(51.27%) Female 1,903,618(44.47%) MOE and UNICEF Primary school Male 2,376,984(55.53%) Secondary education (Intermediate Female 585,937(40.28%) MOE, UNICEF, UNESCO and USAID and Preparatory) Male 868,838(59.72%) Vocational school Female 11,940(19%) MOE and UNICEF Teacher training school Male 50,901(81%) Table 5.1.3 No. -

The Conditions for Educational Achievement of Lower Secondary School Graduates

Rafał Piwowarski THE CONDITIONS FOR EDUCATIONAL ACHIEVEMENT OF LOWER SECONDARY SCHOOL GRADUATES (a research report) Warszawa 2004 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 I. Selection of research sample and organisation of research 12 II. Lower secondary school leaving exam 18 III. Characteristics of the research sample 27 1. Schools 27 2. Teachers 29 3. Students 35 4. Family home and parents 44 IV. Factors Conditioning School Achievement 49 1. Characteristics of Exam Results 49 2. Correlation Analysis 52 2.1. Correlations – Students 54 2.2. Correlations – Schools 58 3. Multiple Regression Analysis 61 3.1. Students – Variables 62 3.2. Students – Factor Analysis 67 3.3. Schools – Variables 70 CONCLUSIONS 73 ANNEXES 79 2 INTRODUCTION The education of children, adolescents and adults has been growing in importance with formal school instruction becoming longer and an increasing number of adults receiving continuous education. As education is becoming more widespread, a growing percentage of particular age groups can benefit from ever higher levels of the educational system. Yet more advanced levels of education are available only to those who perform better. In this context, increasingly measurable and objectively verifiable school achievements can either promote or be a hindrance to further educational, professional and personal careers. The Polish educational system has been undergoing reform since the mid-1990s. The highlights of the educational reform were the establishment of lower secondary schools (gimnazjum) and the introduction of an external system for the assessment of student progress. Since 1999, the educational system has consisted of compulsory uniform six-grade primary schools, compulsory uniform three-grade lower secondary schools (representing the first level of secondary education) and various types of upper secondary school (offering two to three years of instruction). -

Decision Document City Council

2010-05-11 Decision Document - City Council http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2010/cc/decisions/2010-05-11-cc4... Decision Document City Council Meeting No. 49 Contact Marilyn Toft, Manager Meeting Date Tuesday, May 11, 2010 Phone 416-392-7032 Wednesday, May 12, 2010 Start Time 9:30 AM E-mail [email protected] Location Council Chamber, City Hall The Decision Document is for preliminary reference purposes only. Please refer to the Council Minutes for the official record of Council's proceedings. Routine Matters - Meeting 49 RM49.1 Presentation Received Ward: All Moment of Silence City Council Decision May 11, 2010 Members of Council observed a moment of silence and remembered the following persons who passed away: Florence Honderich Louis (Lou) Lockyer, and Carlo Varone May 12, 2010 Members of Council observed a moment of silence and remembered the following person who passed away: Fred Foster Background Information (City Council) Condolence Motion for Florence Honderich (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2010/rm/bgrd/backgroundfile-30358.pdf ) Condolence Motion for Louis (Lou) Lockyer (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2010/rm/bgrd/backgroundfile-30359.pdf ) Condolence Motion for Carlo Varone (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2010/rm/bgrd/backgroundfile-30360.pdf ) Condolence Motion for Fred Foster (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2010/rm/bgrd/backgroundfile-30361.pdf ) 1 of 162 6/18/2010 11:57 PM 2010-05-11 Decision Document - City Council http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2010/cc/decisions/2010-05-11-cc4... RM49.2 ACTION Adopted Ward: All Confirmation of Minutes City Council Decision City Council confirmed the Minutes of Council from the regular meeting held on March 31 and April 1, 2010, and the special meeting held on April 15, 2010, in the form supplied to the Members. -

Taking the SAT® I: Reasoning Test Scoring and Answers Sections

Taking the SAT® I: Reasoning Test Scoring and Answers Sections The materials in these files are intended for individual use by students getting ready to take an SAT Program test; permission for any other use must be sought from the SAT Program. Schools (state-approved and/or accredited diploma-granting secondary schools) may reproduce them, in whole or in part, in limited quantities, for face-to-face guidance/teaching purposes but may not mass distribute the materials, electronically or otherwise. These materials and any copies of them may not be sold, and the copyright notices must be retained as they appear here. This permission does not apply to any third-party copyrights contained herein. No commercial use or further distribution is permitted. The College Board: Expanding College Opportunity The College Board is a national nonprofit membership association whose mission is to prepare, inspire, and connect students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the association is composed of more than 4,300 schools, colleges, universities, and other educational organizations. Each year, the College Board serves over three million students and their parents, 23,000 high schools, and 3,500 colleges through major programs and services in college admissions, guidance, assessment, financial aid, enrollment, and teaching and learning. Among its best-known programs are the SAT®, the PSAT/NMSQT®, and the Advanced Placement Program® (AP®). The College Board is committed to the principles of excellence and equity, and that commitment is embodied in all of its programs, services, activities, and concerns. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.com. Copyright 2003 by College Entrance Examination Board. -

Geography Studies in Poland After 1989 — Selected Issues

MISCELLANEA GEOGRAPHICA – REGIONAL STUDIES ON DEVELOPMENT Vol. 17 • No. 3 • 2013 • pp. 19-25 • ISSN: 2084-6118 • DOI: 10.2478/v10288-012-0042-1 Geography studies in Poland after 1989 — selected issues Abstract Changes in the position of geography as a field of education are examined Mariola Tracz1 in the context of the socio-political transition in Poland after 1989 and in Adam Hibszer2 relation to the changes in higher education. The influences of changes in higher education on the number of geography students in the years 1990–2009, the regional differentiation of interest in geography studies, 1Institute of Geography, and developments in staff and the organization of schools with geography Pedagogical University of Cracow programmes are analysed. In the years 1989/90–2008/09 the number e-mail: [email protected] of higher education schools offering geography programmes increased 2Faculty of Earth Sciences, by one third. The range of programmes offered was widened with new University of Silesia specialisations e-mail: [email protected] Keywords geography studies • higher education institutions • number of students recruitment Received:20 May 2013 © University of Warsaw – Faculty of Geography and Regional Studies Accepted: 1 August 2013 Introduction Since 1989, the onset of political transition in Poland, we have ● a strong interest of young people in training at an academic observed multi-aspectual changes in the system of academic level education. Political transformation became the impulse to modify ● the growing importance of services and an increasing laws on higher education and induce development of a network of demand for highly qualified employees, resulting from the higher education schools.