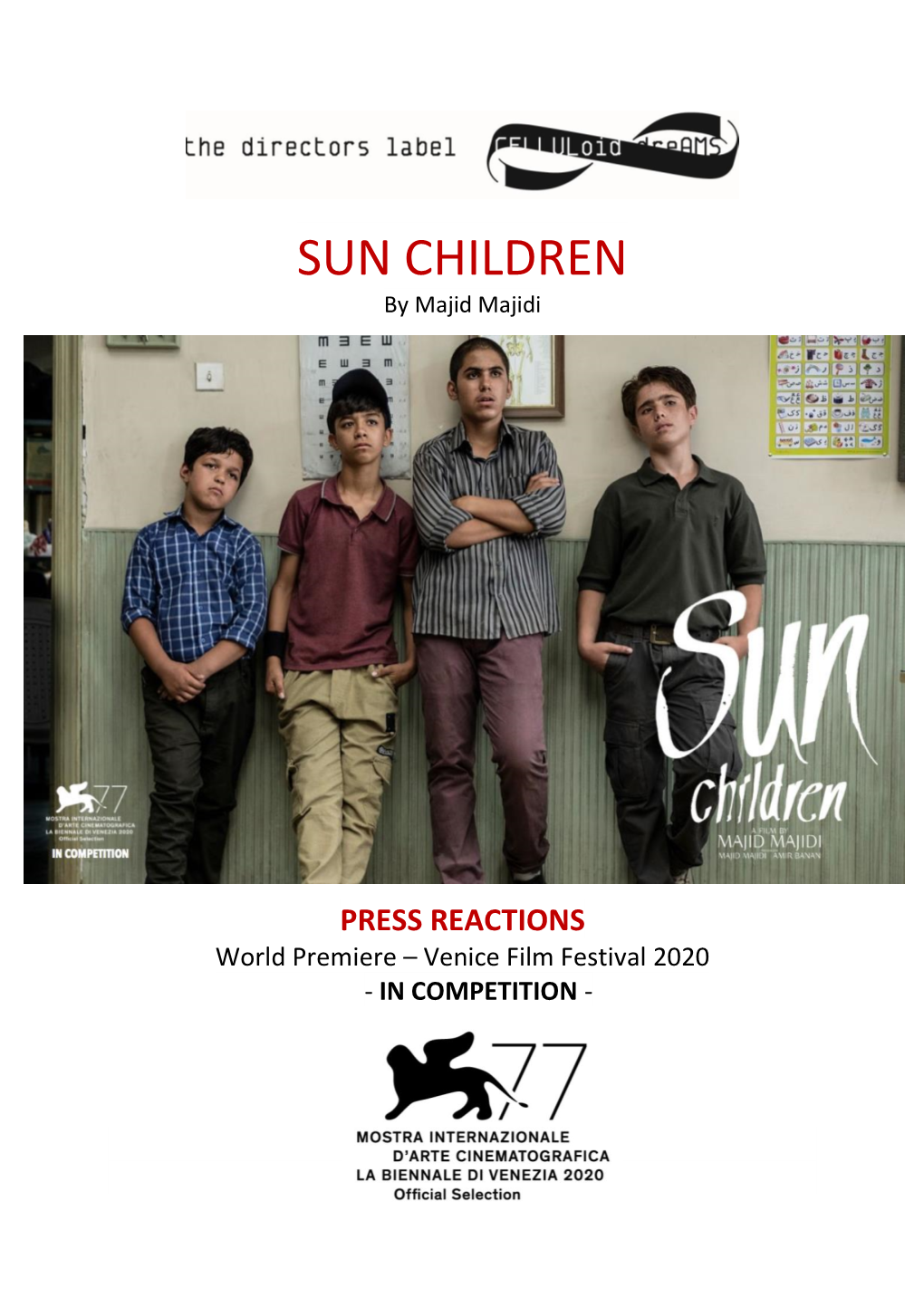

SUN CHILDREN by Majid Majidi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Studies 181B Political Islam and the Response of Iranian

Religious Studies 181B Political Islam and the Response of Iranian Cinema Fall 2012 Wednesdays 5‐7:50 PM HSSB 3001E PROFESSOR JANET AFARY Office: HSSB 3047 Office Hours; Wednesday 2:00‐3:00 PM E‐Mail: [email protected] Assistant: Shayan Samsami E‐Mail: [email protected] Course Description Artistic Iranian Cinema has been influenced by the French New Wave and Italian neorealist styles but has its own distinctly Iranian style of visual poetry and symbolic lanGuaGe, brinGinG to mind the delicate patterns and intricacies of much older Iranian art forms, the Persian carpet and Sufi mystical poems. The many subtleties of Iranian Cinema has also stemmed from the filmmakers’ need to circumvent the harsh censorship rules of the state and the financial limitations imposed on independent filmmakers. Despite these limitations, post‐revolutionary Iranian Cinema has been a reGular feature at major film festivals around the Globe. The minimalist Art Cinema of Iran often blurs the borders between documentary and fiction films. Directors employ non‐professional actors. Male and female directors and actors darinGly explore the themes of Gender inequality and sexual exploitation of women in their work, even thouGh censorship laws forbid female and male actors from touchinG one another. In the process, filmmakers have created aesthetically sublime metaphors that bypass the censors and directly communicate with a universal audience. This course is an introduction to contemporary Iranian cinema and its interaction with Political Islam. Special attention will be paid to how Iranian Realism has 1 developed a more tolerant discourse on Islam, culture, Gender, and ethnicity for Iran and the Iranian plateau, with films about Iran, AfGhanistan, and Central Asia. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

With Holocaust Cartoon Exhibit

Prayer Times Noon:13:03 Evening: 20:15 Dawn: 4:43 (tomorrow) Sunrise: 6:41 (tomorrow) SEPTEMBER 6, 2020 ART&CULTURE I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y www.tehrantimes.com Managing Director: Mohammad Shojaeian Editor-in-Chief: Ali A.Jenabzadeh Iran counters Charlie Editorial Dept.: Fax: (+98 21) 88808214 — 88808895 [email protected] Switchboard Operator: Tel: (+98 21) 43051000 Advertisements Dept.: Telefax: (+98 21) 43051430 Hebdo’s insult to Public Relations Office: Tel: (+98 21) 88805807 Subscription & Distribution Dept.: Tel: (+98 21) 43051603 Webmaster: [email protected] Printed at: Jame Jam Bartar Borna - 44197737 Prophet Muhammad Tehrantimes79 Tehrantimes79 Tehrantimes79 (S) with Holocaust No. 18, Bimeh Alley, Nejatollahi St., Tehran, Iran P.o. Box: 14155-4843 Zip Code: 1599814713 cartoon exhibit 1 “I believe they are trying to promote Shojaei-Tabatabai said that the previous Islamophobia by republishing these cartoons acts by the magazine were not taken into that are against Prophet Muhammad (S),” account when they organized several cartoon asserted Shojaei-Tabatabai who is a prominent exhibits, and this time there are also plans Former secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council Saeid Jalili (L) and cartoonist. to hold an international cartoon exhibit Art Bureau’s Visual Arts Office director Masud Shojaei-Tabatabai visit the cartoon “Creating and promoting hatred, and under the probable title of “The Atonement exhibition “Keep Calm, I Am the Queen” at Abolfazl Aali Gallery in Tehran on June hurting the hearts of millions of Muslims of the Holocaust”. 11, 2019. (Mehr/Shahab Qayyumi) GUIDE TO across the world, is a vain action and this is “The reason lies behind the fact that they SPIRITUAL AWAKENING far from logic,” he said. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Film Press Kit Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt8b69s3fs No online items Guide to the Film Press Kit Collection Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Fax: (805) 893-5749 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/speccoll/speccoll.html © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Guide to the Film Press Kit PA Mss 39 1 Collection Guide to the Film Press Kit Collection Collection number: PA Mss 39 Department of Special Collections Davidson Library University of California, Santa Barbara Processed by: Staff, Department of Special Collections, Davidson Library Date Completed: 10/21/2011 Encoded by: Zachary Liebhaber © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Film Press Kit collection Dates: 1975-2005 Collection number: PA Mss 39 Creator: University of California, Santa Barbara, Arts and Lectures Collection Size: 9 linear ft.(28 boxes). Repository: University of California, Santa Barbara. Library. Dept. of Special Collections Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Abstract: Press kits for motion pictures, mostly independent releases, including promotional material, clippings, and advertising materials. Physical location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access The use of the collection is unrestricted. Many of these films were shown by the UCSB Arts and Lectures series. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Drama Movies

Libraries DRAMA MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 42 DVD-5254 12 DVD-1200 70's DVD-0418 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 8 1/2 DVD-3832 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 8 1/2 c.2 DVD-3832 c.2 127 Hours DVD-8008 8 Mile DVD-1639 1776 DVD-0397 9th Company DVD-1383 1900 DVD-4443 About Schmidt DVD-9630 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Accused DVD-6182 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 1 Ace in the Hole DVD-9473 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 1 Across the Universe DVD-5997 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adam Bede DVD-7149 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs 4 Adjustment Bureau DVD-9591 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs 1 Admiral DVD-7558 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs 5 Adventures of Don Juan DVD-2916 25th Hour DVD-2291 Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert DVD-4365 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 Advise and Consent DVD-1514 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 Affair to Remember DVD-1201 3 Women DVD-4850 After Hours DVD-3053 35 Shots of Rum c.2 DVD-4729 c.2 Against All Odds DVD-8241 400 Blows DVD-0336 Age of Consent (Michael Powell) DVD-4779 DVD-8362 Age of Innocence DVD-6179 8/30/2019 Age of Innocence c.2 DVD-6179 c.2 All the King's Men DVD-3291 Agony and the Ecstasy DVD-3308 DVD-9634 Aguirre: The Wrath of God DVD-4816 All the Mornings of the World DVD-1274 Aladin (Bollywood) DVD-6178 All the President's Men DVD-8371 Alexander Nevsky DVD-4983 Amadeus DVD-0099 Alfie DVD-9492 Amar Akbar Anthony DVD-5078 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul DVD-4725 Amarcord DVD-4426 Ali: Fear Eats the Soul c.2 DVD-4725 c.2 Amazing Dr. -

The Man Who Made It Possible

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13806 Thursday NOVEMBER 12, 2020 Aban 22, 1399 Rabi’ Al awwal 26, 1442 We will use every Komeil Ghasemi new Iran, Qatar to expand Qajar-era paintings by opportunity to lift U.S. gold medalist of co-op in electricity, water Suratgar added to National sanctions Page 2 2012 Olympics Page 3 sectors Page 4 Cultural Heritage list Page 8 Aluminum ingot output rises 69% in 7 months on year TEHRAN — Production of the aluminum The monthly aluminum ingot out- ingot in Iran rose 69 percent during the put has also risen 56 percent to stand at The man who made first seven months of the current Irani- 35,556 tons in the seventh month of the an calendar year (March 20-October 21) present year. compared to the same period of time in Production of the aluminum ingot the past year. in the country is planned to increase 63 The country’s aluminum ingot out- percent by the end of the current Iranian Page 3 put stood at 247,335 tons during the calendar year (March 20, 2021). it possible seven-month period of this year. Continued on page 4 Tehran voices indifference toward result of U.S. election TEHRAN — Deputy Foreign Minister through which the fake grandeur of the Abbas Araghchi has said Iran is neither United States’ democracy was broken in terrified of a second term of the Trump the world. -

Komunikasi Budaya Melalui Media Audio-Visual (Studi Atas Film Children of Heaven, the Color of Paradise, Dan Baran Karya Majid Majidi)

LAPORAN PENELITIAN KOMUNIKASI BUDAYA MELALUI MEDIA AUDIO-VISUAL (STUDI ATAS FILM CHILDREN OF HEAVEN, THE COLOR OF PARADISE, DAN BARAN KARYA MAJID MAJIDI) Ketua Peneliti Dr. A. Rani Usman, M.Si NIDN: ID Peneliti: Anggota: Ahmad Fauzan, M.Ag Bustami, S. Sos.I Nazarullah, S.Sos.I Hayatullah Zuboidi, S.Sos.I Kategori Penelitian Penelitian Pengembangan Program Studi Bidang Ilmu Kajian Dakwah dan Komunikasi Sumber Dana DIPA UIN Ar-Raniry Tahun PUSAT PENELITIAN DAN PENERBITAN LEMBAGA PENELITIAN DAN PENGABDIAN KEPADA MASYARAKAT UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI AR-RANIRY BANDA ACEH OKTOBER 201 LEMBARAN IDENTITAS DAN PENGESAHAN LAPORAN PENELITIAN PUSAT PENELITIAN DAN PENERBITAN LP2M UIN AR-RANIRY TAHUN 201 a. Judul Penelitian : Komunikasi Budaya Melalui Media Audio-Visual (Studi Atas Film Children of Heaven, the Color of Paradise, dan Baran Karya Majid Majidi) b. Kategori Penelitian : Penelitian Pengembangan Program Studi c. No. Registrasi : - d. Bidang Ilmu yang diteliti : Dakwah dan Komunikasi Peneliti/Ketua Peneliti a. Nama Lengkap : Dr. A. Rani Usman, M.Si b. Jenis Kelamin : Laki-Laki (Kosongkan bagi Non PNS) c. NIP : d. NIDN : e. NIPN (ID Peneliti) : f. Pangkat/Gol. : Pembina Utama / IV/c g. Jabatan Fungsional : Lektor Kepala h. Fakultas/Prodi : Pascasarjana / KPI i. Anggota Peneliti 1 Nama Lengkap : Ahmad Fauzan, M.Ag Jenis Kelamin : Laki-Laki Fakultas/Prodi : Pascasarjan / IAI j. Anggota Peneliti 2 Nama Lengkap : Nazarullah, S.Sos.I Jenis Kelamin : Laki-laki Fakultas/Prodi : Pascasarjana / KPI k Anggota Peneliti 3 : Bustami, S. Sos.I Nama Lengkap : Laki-laki Jenis Kelamin : Pascasarjana / KPI Fakultas/Prodi : Hayatullah Zuboidi, S.Sos.I l Anggota Peneliti : Perempuan Nama Lengkap : Pascasarjana / KPI Jenis Kelamin Fakultas / Prodi Lokasi Penelitian : Banda Aceh Jangka Waktu Penelitian : (enam) Bulan Th Pelaksanaan Penelitian : Jumlah Biaya Penelitian : Rp. -

13881 Saturday FEBRUARY 13, 2021 Bahman 25, 1399 Rajab 1, 1442

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13881 Saturday FEBRUARY 13, 2021 Bahman 25, 1399 Rajab 1, 1442 Ghalibaf: Iran’s strategic Ali Moradi Iran sits at UN TIR Even ‘illegal migrants’ principle is to develop nominated for executive board for 3rd in Iran will get ties with China Page 2 IWF presidency Page 3 consecutive time Page 4 COVID-19 vaccine Page 7 Iran’s top judge holds talks with Iraqi leaders SPECIAL ISSUE TEHRAN - Iran’s Judiciary Chief Ebra- him Raeisi held talks with several Iraqi political and judicial leaders including President Barham Salih, Prime Min- ister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, and Head of Iraq’s Supreme Judicial Council Faiq Zaidan. The man of On Monday, February 8, Ayatollah Raisi paid a two-day visit to Iraq. During his meeting with his Iraqi counterpart, the two sides signed three memoranda of understanding to boost judicial and legal cooperation between the two neighboring countries. theoretical Continued on page 3 Bandar Abbas-Latakia direct shipping line to be launched by early Mar. battlefields TEHRAN - Iran is going to establish a direct shipping line between its south- ern port of Bandar Abbas and Syria’s Mediterranean port of Latakia on March In memory of Ayatollah 10, Head of Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce Keyvan Kashefi announced. Mohammad Taghi Continued on page 4 Mesbah Yazdi, the Iranian “Yadoo” tops at 39th renowned theorist and Fajr Film Fsetival philosopher TEHRAN – War drama “Yadoo” was the top winner of the 39th Fajr Film Festival by garnering awards in several categories, including best film and best director.