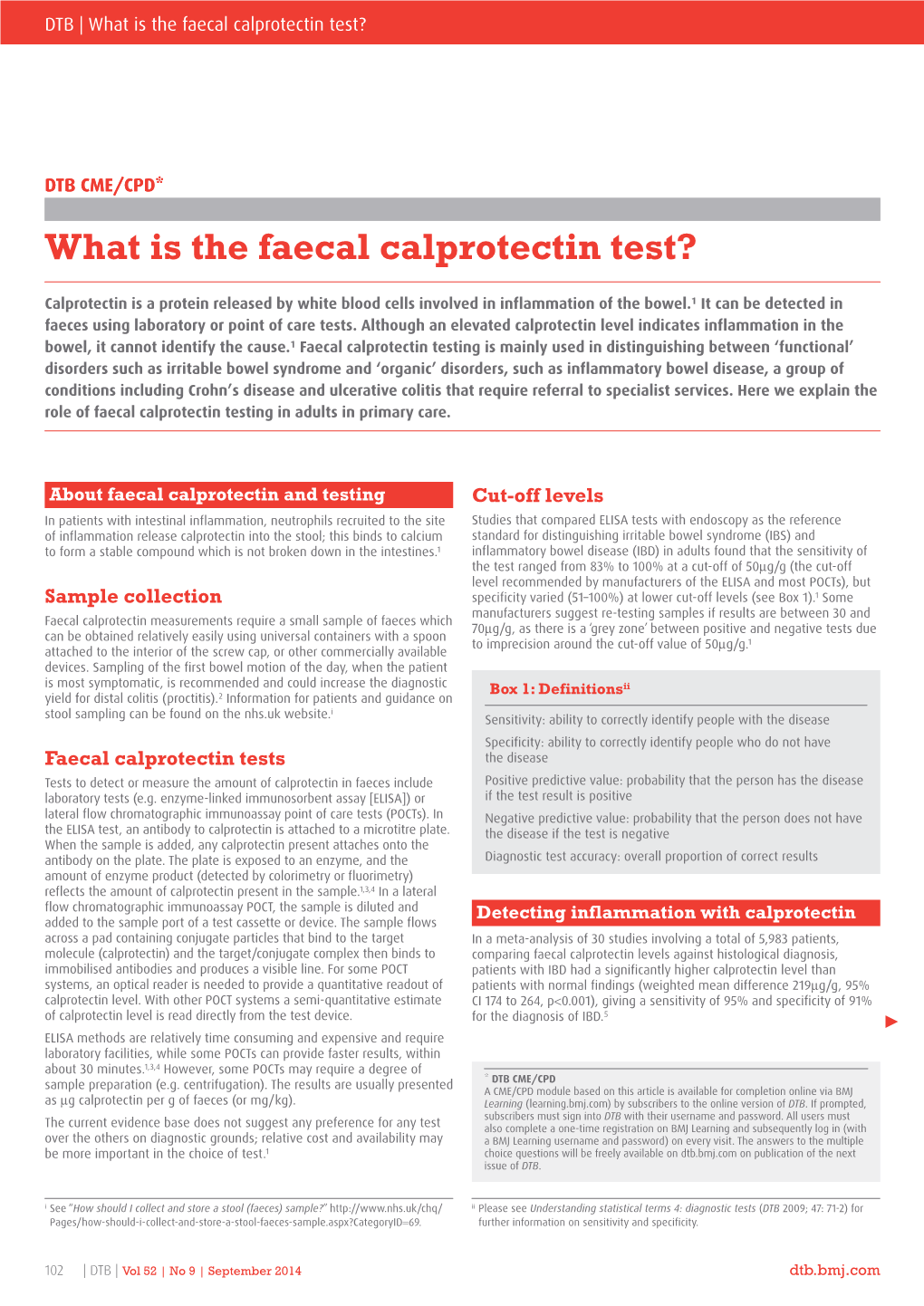

What Is the Faecal Calprotectin Test?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

329 Fecal Calprotectin Testing

Medical Policy Fecal Calprotectin Testing Table of Contents • Policy: Commercial • Coding Information • Information Pertaining to All Policies • Policy: Medicare • Description • References • Authorization Information • Policy History Policy Number: 329 BCBSA Reference Number: 2.04.69 NCD/LCD: N/A Related Policies Fecal Analysis in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Dysbiosis, #556 Policy Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Medicare HMO BlueSM and Medicare PPO BlueSM Members Fecal calprotectin testing may be considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY for the evaluation of patients when the differential diagnosis is inflammatory bowel disease or noninflammatory bowel disease (including irritable bowel syndrome) for whom endoscopy with biopsy is being considered. Fecal calprotectin testing is considered INVESTIGATIONAL in the management of bowel disease, including the management of active inflammatory bowel disease and surveillance for relapse of disease in remission. Prior Authorization Information Inpatient • For services described in this policy, precertification/preauthorization IS REQUIRED for all products if the procedure is performed inpatient. Outpatient • For services described in this policy, see below for products where prior authorization might be required if the procedure is performed outpatient. Outpatient Commercial Managed Care (HMO and POS) Prior authorization is not required. Commercial PPO and Indemnity Prior authorization is not required. Medicare HMO BlueSM Prior authorization is not required. Medicare PPO BlueSM Prior authorization is not required. 1 CPT Codes / HCPCS Codes / ICD Codes Inclusion or exclusion of a code does not constitute or imply member coverage or provider reimbursement. Please refer to the member’s contract benefits in effect at the time of service to determine coverage or non-coverage as it applies to an individual member. -

Fecal Calprotectin Testing &

FECAL CALPROTECTIN TESTING & IBD Get the inside scoop from your poop! If you have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), you know that inflammation in your gastrointestinal tract can cause flares. When flares strike, you might experience painful cramps, diarrhea, bleeding, and fever. But how do you know if these symptoms are from a flare or some other cause? fCal is useful in patients with inactive ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, as it can help predict relapse and allow early treatment. The clue is in your poo… Benefits of Fecal Calprotectin (fCal) testing Non-invasive fCal testing requires no bowel preparation. Samples can be collected in the privacy of your home. You may still need to have a colonoscopy or biopsy. Identifies relapse or flares It’s important to know whether your symptoms are due to IBD or some other cause, so that your doctor can manage your symptoms appropriately. Large amounts of fCal in your stool mean you are likely experiencing IBD relapse. Low to normal levels usually mean your symptoms are due to something else, like irritable bowel syndrome. Monitors response to ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease treatment fCal levels may also be useful in monitoring disease activity and how well you are responding to your treatment. It may even help your doctor predict relapse if your fCal levels are high. When? There are no clear guidelines on how often you should take the fCal test, and fCal levels may vary for each person. It may be useful to monitor your level when your IBD is in remission. -

Calprotectin – Scientific Literature R-Biopharm – for Reliable Diagnostics

R-Biopharm – for reliable diagnostics Calprotectin – scientific literature R-Biopharm – for reliable diagnostics Content 1. Highlights ............................................................................................................3 2. Benefits of calprotectin management ..................................................................4 3. Calprotectin as a marker for the diagnosis of IBD ................................................5 3.1. Adult patients ......................................................................................................5 3.2. Pediatric patients ................................................................................................5 3.3. Cost-effectiveness of calprotectin measurements for suspected inflammatory bowel disease ................................................................................6 3.4. Diagnostic algorithm for suspected inflammatory bowel disease .........................6 4. Calprotectin as a surrogate marker for disease activity in IBD ������������������������������7 5. Calprotectin as a surrogate marker for mucosal healing in IBD ...........................8 6. Calprotectin as a predictive marker for relapse in IBD �����������������������������������������9 7. Calprotectin as a predictive marker for post-operative relapse in Crohn’s disease .............................................................................................10 8. Calprotectin as an aid in the decision to stop an IBD drug ................................. 11 9. Calprotectin and -

Calprotectin and Calgranulin C Serum Levels in Bacterial Sepsis

Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 93 (2019) 219–226 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/diagmicrobio ☆ Calprotectin and calgranulin C serum levels in bacterial sepsis Eva Bartáková a,MarekŠtefan a,Alžběta Stráníková a, Lenka Pospíšilová b, Simona Arientová a,Ondřej Beran a, Marie Blahutová b, Jan Máca a,c,MichalHoluba,⁎ a Department of Infectious Diseases, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and Military University Hospital Prague, U Vojenské nemocnice 1200, 169 02 Praha 6, Czech Republic b Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Military University Hospital Prague, U Vojenské nemocnice 1200, 169 02 Praha 6, Czech Republic c Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, University Hospital of Ostrava, 17. listopadu 1790/5, 708 52 Ostrava-Poruba, Czech Republic article info abstract Article history: The aim of this study was to evaluate the serum levels of calprotectin and calgranulin C and routine biomarkers in Received 26 March 2018 patients with bacterial sepsis (BS). The initial serum concentrations of calprotectin and calgranulin C were signif- Received in revised form 2 October 2018 icantly higher in patients with BS (n = 66) than in those with viral infections (n = 24) and the healthy controls Accepted 10 October 2018 (n = 26); the level of calprotectin was found to be the best predictor of BS, followed by the neutrophil- Available online 17 October 2018 lymphocyte count ratio (NLCR) and the level of procalcitonin (PCT). The white blood cell (WBC) count and the NLCR rapidly returned to normal levels, whereas PCT levels normalized later and the increased levels of Keywords: Sepsis calprotectin, calgranulin C, and C-reactive protein persisted until the end of follow-up. -

Calprotectin-Mediated Zinc Chelation Inhibits Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Protease Activity in Cystic Fibrosis Sputum

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432981; this version posted February 26, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Calprotectin-mediated zinc chelation inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa protease activity in cystic fibrosis sputum Danielle M. Vermilyeaa, Alex W. Crockera, Alex H. Giffordb,c, and Deborah A. Hogana,# a Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire b Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire c The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Lebanon, New Hampshire Running title: Calprotectin inhibits P. aeruginosa proteases # Address correspondence to: Department of Microbiology and Immunology Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth Rm 208 Vail Building Hanover, NH 03755 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (603) 650-1252 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.25.432981; this version posted February 26, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Abstract 2 Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces pathways indicative of low zinc availability in the cystic 3 fibrosis (CF) lung environment. To learn more about P. aeruginosa zinc access in CF, we grew 4 P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 directly in expectorated CF sputum. -

Comparing of Faecal Calprotectin Levels in Patients with Osteoarthritis Taking Nsaid Treatment and Patients Without Nsaids Therapy

Original Research Article: (2020), «EUREKA: Health Sciences» full paper Number 2 COMPARING OF FAECAL CALPROTECTIN LEVELS IN PATIENTS WITH OSTEOARTHRITIS TAKING NSAID TREATMENT AND PATIENTS WITHOUT NSAIDS THERAPY Olena Gubska1 [email protected] Andrii Kuzminets1 [email protected] Artem Panin1 [email protected] 1Department of Therapy, Infectious Disease and Dermatology Postgraduate Education Bogomolets National Medical University 13 T. Shevchenko blvd., Kyiv, Ukraine, 01601 Abstract Faecal calprotectin (FC) level can be increased in several conditions, which are characterised by neutrophilic inflammation. Some medications, particularly NSAIDs, can elevate its level as well. NSAIDs are taken by patients in many chronic conditions, includ- ing osteoarthritis (OA). On the other hand, there is growing evidence that osteoarthritis is not only a degenerative disease, but it has a significant inflam- matory component. The role of systemic inflammation is well-known in inflammatory joint diseases, but there is some evidence that it can play an essential role in the OA as well. It can suggest that in the OA, the inflammatory changes could be found in the different organs and systems. The aim of this study was to investigate the FC level in patients with osteoarthritis depending on the NSAIDs intake and to compare it to the FC levels in healthy adults. Materials and methods. In this small observational study, we evaluated the FC levels in patients suffering from OA (36 per- sons), divided them into two groups depending on their NSAIDs intake, and compared it to FC levels in healthy participants (12 persons). We compared the FC levels depending on the selectivity of the NSAIDs taken by our participants, as well. -

Calprotectin Poster

70th AACC Annual Scientific Meeting & Clinical Lab Expo July 29 – August 2, 2018, Chicago, Illinois, USA Calprotectin Antibodies With Different Binding Specificities Can Be Used as Tools to Detect Multiple Calprotectin Forms 1 Laura-Leena Kiiskinen1, Sari Tiitinen 1Medix Biochemica, Klovinpellontie 3, FI-02180 Espoo, Finland Calprotectin –A Pro-Inflammatory Protein Materials & Methods Calprotectin (leucocyte L1-protein) We have developed five mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) is a pro-inflammatory protein against human calprotectin: 3403 (#100460), 3404 (#100468), primarily secreted by neutrophils, 3405 (#100469), 3406 (#100470) and 3407 (#100618). Binding macrophages and monocytes at the specificities of the antibodies were studied in fluorescent site of inflammation1–4. Neutrophils immunoassays (FIA) using purified recombinant monomeric accumulate in mucosa, where calprotectin subunits S100A8 (#710018; Medix Biochemica) calprotectin is released and easily and S100A9 (#710019; Medix Biochemica), and the S100A8/A9 detectable4. complex (#610061; Medix Biochemica) as antigens. Calprotectin is comprised of two Antigens were coated onto a microtiter plate (#473709; NUNC®) calcium-binding monomers, a at 50 ng/well, blocked for 1h at room temperature, and 93-amino-acid S100A8 (MRP-8) and antibodies added at concentrations 31–1,000 ng/mL. Bound a 114-amino-acid S100A9 (MRP-14). antibodies were detected using an europium (Eu)-labeled Dimers pair non-covalently with each DELFIA® Eu-N1 Rabbit Anti-Mouse IgG antibody (#AD0207; other, forming heterotetramers. S100A8 PerkinElmer) as described previously9. and S100A9 both contain two EF-hand The specificities of calprotectin antibody pairs were studied in type Ca2+ binding sites (Figure 1). sandwich FIA. Capture antibodies (150 ng/well) were incubated Elevated serum or fecal calprotectin with the S100A8/A9 complex at concentrations 0.15–1,000 levels are indicative of several ng/mL. -

The Role of Calprotectin (S100A8/A9) in the Pathogenesis of Glomerulonephritis and ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Ruth Jennifer Pepp

The role of Calprotectin (S100A8/A9) in the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis and ANCA-associated vasculitis Ruth Jennifer Pepper UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Declaration of originality I, Ruth Pepper, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicted in the thesis. 2 Abstract Glomerulonephritis is a common cause of end-stage renal failure and a feature of ANCA- associated vasculitis (AAV). AAV is an example of a small vessel vasculitis, characterised by inflammation of the endothelium and glomeruli in which the interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells play a crucial role. Macrophages have been demonstrated to have a critical role during the initiation and progression of glomerulonephritis, with the persistence of macrophages in the renal biopsy being associated with a poorer outlook. Calprotectin (also termed S100A8/A9, mrp8/14), is a complex of 2 small calcium binding proteins that is abundantly expressed in neutrophils and monocytes as well as early infiltrating macrophages and is a known ligand of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE). There is growing evidence in animal models and in patients with autoimmune diseases, of calprotectin being involved in the inflammatory response, as well as being a marker of activation of innate immunity. I have initially characterised the presence of calprotectin-positive cells in the renal biopsy of patients with focal and crescentic AAV glomerulonephritis, therefore linking the presence of these cells with renal outcome. Patients with active AAV have elevated serum calprotectin levels, as well as significant expression on neutrophils and monocytes, which although decrease during remission, does not normalise. -

FAECAL CALPROTECTIN Who Should Be

FAECAL CALPROTECTIN Who should be tested? Calprotectin is an S-100 protein (mainly produced by neutrophils) measured in stool and is a non-specific marker of inflammation. It is relatively sensitive for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) at around 97%, but is NOT very specific (approximately 70%). In children over 5 years of age with a high clinical suspicion of IBD (persistent diarrhoea with or without blood, abdominal pain, weight loss, family history of IBD) and in the context of a negative stool infection screen, we recommend urgent referral to the RHSC GI team with a calprotectin sent concurrently. Like adult practice, the relevance of faecal calprotectin testing is to determine who requires further, more invasive, investigation and to help understand if inflammation is playing a part in the patient’s symptoms (i.e. IBS versus IBD). We are keen that this test is performed in the workup of relevant children along with relevant blood testing and either performed in primary care or at RHSC as part of the open access service. Who should not be tested? Not only are children under the age of 5 years less likely to present with IBD but baseline faecal calprotectin is higher in this age group making interpretation more difficult therefore this should be avoided. Faecal calprotectin should also not be performed in children on aspirin or NSAIDs or who are recovering from (within 4 weeks) an obvious gastrointestinal infection; it should be routine to send stools concurrently for bacteriology (C diff in selected cases if there is suspicion and risk factors) and virology when requesting a faecal calprotectin. -

Calprotectin: an Ignored Biomarker of Neutrophilia in Pediatric Respiratory Diseases

children Review Calprotectin: An Ignored Biomarker of Neutrophilia in Pediatric Respiratory Diseases Grigorios Chatziparasidis 1 and Ahmad Kantar 2,* 1 Primary Cilia Dyskinesia Unit, School of Medicine, University of Thessaly, 41110 Thessaly, Greece; [email protected] 2 Pediatric Asthma and Cough Centre, Instituti Ospedalieri Bergamaschi, University and Research Hospitals, 24046 Bergamo, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Calprotectin (CP) is a non-covalent heterodimer formed by the subunits S100A8 (A8) and S100A9 (A9). When neutrophils become activated, undergo disruption, or die, this abundant cytosolic neutrophil protein is released. By fervently chelating trace metal ions that are essential for bacterial development, CP plays an important role in human innate immunity. It also serves as an alarmin by controlling the inflammatory response after it is released. Extracellular concentrations of CP increase in response to infection and inflammation, and are used as a biomarker of neutrophil activation in a variety of inflammatory diseases. Although it has been almost 40 years since CP was discovered, its use in daily pediatric practice is still limited. Current evidence suggests that CP could be used as a biomarker in a variety of pediatric respiratory diseases, and could become a valuable key factor in promoting diagnostic and therapeutic capacity. The aim of this study is to re-introduce CP to the medical community and to emphasize its potential role with the hope of integrating it as a useful adjunct, in the practice of pediatric respiratory medicine. Citation: Chatziparasidis, G.; Kantar, Keywords: calprotectin; S100A8/A9; children; lung A. Calprotectin: An Ignored Biomarker of Neutrophilia in Pediatric Respiratory Diseases. Children 2021, 8, 428. -

Calprotectin, Stool

Test Summary Calprotectin, Stool be used as 1 of the initial tests in patients with suspected IBD; Test Code: 16796 levels can help avoid unnecessary colonoscopy, as normal levels are not typically associated with active IBD.2 Conversely, Specimen Requirements: 1 g frozen stool; 0.3 g levels above normal are consistent with organic diseases such minimum as IBD and colorectal cancer, and warrant consideration of colonoscopy.2,4 CPT Code*: 83993 Calprotectin testing can also be used to monitor response to IBD treatment, since lower concentrations correlate with less severe disease and better response to treatment.5 CLINICAL USE The correlation, however, is higher in patients with colonic • Diagnose inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) than ileal disease activity.6,7 Failure of calprotectin level to normalize with treatment is considered an indication for • Differentiate IBD from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) further endoscopic evaluation, regardless of symptoms.8 • Monitor patients with IBD for treatment response and Among IBD patients who are in remission, calprotectin helps relapse predict those who will experience a relapse. Gisbert et al CLINICAL BACKGROUND showed that an elevated calprotectin concentration predicted Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by chronic, relapse during the next 12 months with a sensitivity of 69% relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract lining. and a specificity of 75%.9 Costa et al showed that Crohn The 2 primary forms of IBD are Crohn disease and ulcerative disease patients in remission had a 2-fold, and ulcerative colitis, which share clinical symptoms such as abdominal colitis patients a 14-fold, increased risk of relapse when the pain, dyspepsia, and diarrhea that can be profuse and bloody.1 stool calprotectin concentration was elevated.10 Another Abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and diarrhea (non-bloody) are study showed that Crohn disease patients with an elevated also seen in patients with IBS. -

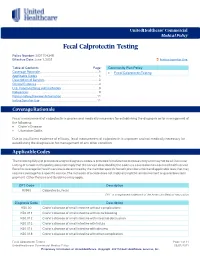

Fecal Calprotectin Testing

UnitedHealthcare® Commercial Medical Policy Fecal Calprotectin Testing Policy Number: 2021T0434R Effective Date: June 1, 2021 Instructions for Use Table of Contents Page Community Plan Policy Coverage Rationale ........................................................................... 1 • Fecal Calprotectin Testing Applicable Codes .............................................................................. 1 Description of Services ..................................................................... 3 Clinical Evidence ............................................................................... 4 U.S. Food and Drug Administration ................................................ 9 References ......................................................................................... 9 Policy History/Revision Information..............................................11 Instructions for Use .........................................................................11 Coverage Rationale Fecal measurement of calprotectin is proven and medically necessary for establishing the diagnosis or for management of the following: • Crohn’s Disease • Ulcerative Colitis Due to insufficient evidence of efficacy, fecal measurement of calprotectin is unproven and not medically necessary for establishing the diagnosis or for management of any other condition. Applicable Codes The following list(s) of procedure and/or diagnosis codes is provided for reference purposes only and may not be all inclusive. Listing of a code in this policy does not imply that