“Bringing the Region to the World and the World to the Region:”1 the Impact of Place on the Role of Universities in Non-Metropolitan Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-LPN BN Professional Practice (Clinical) Preparation Guide

Post-LPN BN Professional Practice (Clinical) Preparation Guide Post-LPN BN students registering in professional practice (clinical) courses must be prepared to demonstrate, at a minimum, the knowledge, skills, and clinical behaviours outlined in the College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Alberta, Competency Profile for LPN’s, 5th edition, February, 2020 Students are required to seek self-remediation as needed prior to registration in NURS 401, NURS 435, and NURS 437. Throughout the clinical courses, students (with guidance from instructors/preceptors) will be expected to progress toward meeting College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta, Entry-Level Competencies for the Practice of Registered Nurses (March 2019) Read this entire document prior to planning to register in clinical courses to understand all requirements. Note: A program GPA of 3.0 is required for all clinical courses. Students are responsible for: • meeting all deadlines • completing pre-requisite courses • earning a program GPA of 3.0 • submitting pre-requisite clinical placement documentation • reviewing Alberta Health Services (AHS) and other clinical placement agency modules; and • registering in clinical courses prior to deadlines. Clinical Courses Clinical courses are offered three times per year and are “paced” over a four-month period. A paced course means that students work together with set timelines and due dates to complete the course. One clinical course can be taken per term. • Fall term: September–December • Winter term: January–April • Spring term: April-July for NURS 401; May–August for NURS 435, 437, 441 NURS 401: Professional Practice with Adults Experiencing Health Alterations • An invigilated Medication Safety and Calculation Quiz must be successfully completed in the first month of the course, prior to the four-week clinical rotation. -

Decolonizing Description at the University of Alberta Libraries

Unsettling Our Practices: Decolonizing Description at the University of Alberta Libraries Sharon Farnel, Denise Koufogiannakis, Ian Bigelow, Anne Carr-Wiggin, Debbie Feisst, Kayla Lar-Son, Sheila Laroque Edmonton, AB, Canada T6G 2R3 · We are located on Treaty 6 / Métis Territory. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Decolonizing Description Current Initiatives Working Group - The final report of the Truth and - Libraries, as sites of learning in “promote initiatives in all types of As part of UAL’s Academic Residency Program, Sheila Reconciliation Commission of and of themselves as well as key libraries to advance reconciliation Laroque has been hired to work on these recommendations of Canada (TRC) included 94 Calls to units within post-secondary by supporting the TRC Calls to - Fall of 2016, University of Alberta Libraries (UAL) the Working Group. Some of the things she is focusing on Action was released in 2015 institutions, have a responsibility Action and to promote collaboration struck a Decolonizing Description Working Group - These Calls to Action focus on the and opportunity to contribute to in these issues across the include: (DDWG) to investigate, define, and propose a plan of educational system, as it has reconciliation through Canadian library communities” (p. - Outreach with universities and institutions that have contributed to the negative collaborations and partnerships 1). action for how we could represent Indigenous peoples already begun or are doing similar work relationship between Indigenous - The Canadian -

Letter from Scientists Regarding the Boreal Forest

Letter from scientists regarding the Boreal Forest Dear Premier Charest, In a letter sent in May 2007, 1,500 scientists from more than 50 countries around the world, including 71 from Quebec, asked Canadian government leaders to ensure the protection of at least 50% of Canada’s Boreal forest. Since making this appeal, we have followed the progression of this file with keen interest. We were delighted to hear, on November 15, 2008, the commitment that "by 2015, [...] 50% of the area covered by the Plan Nord will be protected from industrial, mining and energy development." This commitment was reiterated in March in your speech at Mont Saint-Bruno National Park announcing that Quebec had reached its objective of 8% protected areas. Your commitment deserves our public support; in protecting northern Quebec’s natural environment and ensuring responsible development in the rest of the area, your government will set in motion one of the most ambitious sustainable development and nature conservation projects in North America, and one that could serve as a model for the rest of the world. Scientists have already catalogued some of the natural resources that constitute the natural heritage of northern Quebec. In terms of wildlife, northern Quebec provides habitat for 340 million birds,i more than a million tundra caribou and some of the largest populations of freshwater fish in North America. However, the populations of some species are too low: the woodland caribou, the wolverine and the golden eagle are all on Quebec’s threatened or vulnerable species lists. In terms of the region’s ecological benefits to society, including water filtration and carbon storage, their value is estimated at 13.8 times the value of the natural resources extracted from it each year. -

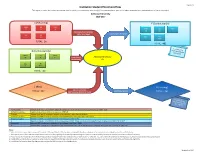

Institution Student Enrolment Flow

Page 1 of 2 Institution Student Enrolment Flow This report provides the student enrolment data for public post-secondary institution(s) for a given academic year and student movement into, within and out of the institution(s). Ambrose University 2017-2018 A (Returning) E (Continuing On) CARU UU POLY 7 6 4 CARU UU POLY 70 8 5 From System to Institution (After Year Away) Continuing in the System CCC IAI 4 16 CCC IAI 10 424 TOTAL:Alberta 30University of the Arts TOTAL: 472 B (Continuing Into) CARU UU POLY 35 5 7 From System Ambrose University to Institution 701 CCC IAI 5 431 TOTAL: 458 C (New) G (Leaving) New to Institution Leaving the System TOTAL: 213 (Not in System for Prev. 6 Years) TOTAL: 229 A (Returning) Students that were not enrolled in 2016-17, but had an enrolment record at some point between 2011 - 2016 B (Continuing into) Students that were enrolled in the system in 2016-17 C (New) Students that had NO enrolment records in the previous 6 years (New to system) D (Student Cohort) Students enrolled full-time or part-time in the institution(s) in the cohort year (2017-2018) E (Continuing On) Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2018-2019) F Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2018-2019), and received a credential from Ambrose University in 2017-2018 G (Leaving) Students NOT enrolled at an institution in the following year (2018-2019) H Students NOT enrolled in an institution for the following year (2018-2019), but received a credential from Ambrose University in 2017-2018 Notes: 1. -

David Suzuki

David Suzuki David Takayoshi Suzuki (born March 24, 1936) is a Canadian scientist, environmental activist, and broadcaster. Suzuki received his BA from Amherst College in Massachusetts in 1958 and his Ph.D in zoology from the University of Chicago in 1961. Since the mid 1970s, Suzuki has become known for his TV and radio series and books about nature and the environment. For his work popularizing science and environmental issues, he has been presented with 19 honorary degrees (all doctorates) from schools in Canada, The United States, and Australia. Early in his research career he studied genetics, using the popular model organism Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies). To be able to use his initials in naming any new genes he found, he studied Drosophila temperature- sensitive phenotypes (DTS). He gained several international awards for his research into these mutations. He was a professor in the zoology department at the University of British Columbia for over thirty years (from 1963 until his retirement in 2001) and has since been professor emeritus at a university research institute. Since 1979, Suzuki has hosted The Nature of Things, a CBC television show that has aired in nearly fifty countries worldwide. In this show, Suzuki aimed to stimulate interest in the natural world, to point out what some of the threats to human well-being and wildlife habitat were, and to point out some promising alternatives in terms of sustainability. Suzuki has been a very prominent proponent of renewable energy sources and the soft energy path. A Planet for the Taking, a 1985 hit series, averaged about 2 million viewers per episode and earned him a United Nations Environment Medal in 1985. -

7. Undergraduate Fees and Refunds

Undergraduate 7. Undergraduate Fees Calendar Home and Refunds General Information The following fees are effective for students registering with a start date of Student September 1, 2018 to August 31, 2019. Support Services Course fees are all-inclusive, and are calculated by combining the tuition fees, Admission, learning resources fee, and Students’ Registration Union and Alumni Relations fees. and Evaluation If you formally withdraw from your individualized study course or your Undergraduate grouped study course, you must follow the Programs regulations in the following sections that apply to you. Undergraduate Courses For more information related to undergraduate fees and refunds, use the Examinations links on the left. and Grades Undergraduate Fees and Information effective Sept. 1, 2018 to Refunds Aug. 31, 2019. Fees Updated June 18 2018 by laurab Refunds Delinquent Accounts Receipts Form T2202A The content on these pages was captured on January 11, 2019, and is effective January 1, 2019 to August 31, 2019. The online Calendar is the official version. If there are any discrepancies between this publication and the online version, the online Calendar will be binding. Undergraduate Undergraduate Fees and Calendar Home Refunds General Information 7.1 Fees Student Support The following fees are effective for Services students registering with a start date of September 1, 2018 to August 31, 2019. Admission, Registration Course fees are all-inclusive and are calculated by combining the tuition fees, and Evaluation learning resources fee, and Students' Undergraduate Union and Alumni Relations fees. Choose the fees relevant to your situation from Programs the links on the left. Undergraduate Courses Information effective Sept. -

Institution Student Enrolment Flow

Page 1 of 2 Institution Student Enrolment Flow This report provides the student enrolment data for public post-secondary institution(s) for a given academic year and student movement into, within and out of the institution(s). Ambrose University 2016-2017 A (Returning) E (Continuing On) CARU UU POLY 12 9 9 CARU UU POLY 73 12 6 From System to Institution (After Year Away) Continuing in the System CCC IAI 4 16 CCC IAI 7 428 TOTAL: 36 TOTAL: 482 B (Continuing Into) CARU UU POLY 43 8 5 From System Ambrose University to Institution 725 CCC IAI 4 431 TOTAL: 457 C (New) G (Leaving) New to Institution Leaving the System TOTAL: 232 (Not in System for Prev. 6 Years) TOTAL: 243 A (Returning) Students that were not enrolled in 2015-16, but had an enrolment record at some point between 2010 - 2015 B (Continuing into) Students that were enrolled in the system in 2015-16 C (New) Students that had NO enrolment records in the previous 6 years (New to system) D (Student Cohort) Students enrolled full-time or part-time in the institution(s) in the cohort year (2016-2017) E (Continuing On) Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2017-2018) F Students enrolled in an institution for the following year (2017-2018), and received a credential from Ambrose University in 2016-2017 G (Leaving) Students NOT enrolled at an institution in the following year (2017-2018) H Students NOT enrolled in an institution for the following year (2017-2018), but received a credential from Ambrose University in 2016-2017 Notes: 1. -

Welcome to CFB EDMONTON

Welcome to CFB EDMONTON CAFconnection.ca/Edmonton For over 30 years we have been a community of families helping families. Children, pets, partners, and friends, we are there for you every step of the way. The Edmonton Garrison Military Family Resource Centre supports military families as they navigate the unique challenges of military life through programs and services that enhance their strength and resilience. 2 780-973-4011 ext. 6300 | CAFconnection.com/Edmonton MFRC Table of Contents SERVICES Welcome to Edmonton......................................................................5 Military Family Resource Centre...................................................6 Military and Community Services..............................................10 Welcome Services..............................................................................13 WELCOME Alberta Health Care..........................................................................14 Settling In Driving/Transportation....................................................................16 Education........................................................................................... 17 ALBERTA HEALTH ALBERTA Employment Resources....................................................................20 Francophone Resources....................................................................21 Edmonton and Area..........................................................................22 Points of Interest...............................................................................27 -

Introduction

University of Lethbridge STUDENT FEE REPORT – 2004-05 Introduction • Instructional fees are only one of several financial components that determine the cost of education at the University of Lethbridge. In addition to tuition and other mandatory fees, related costs including textbooks, parking, housing and food must be considered. This report compares the changing costs of education over a ten-year period from 1994-95 to 2004-05 at the University of Lethbridge. These costs are then compared to other Western Canadian Universities for the same years. With increasing operating costs and low provincial grants, it is important to maintain current levels of enrolment. Maintaining competitive fees is one way to achieve this. • The University Calendar, Proposed Fees and Rates report, and the Student Debt report provided in depth information on all fees charged to students at the University of Lethbridge. This report gives the amount of a fee, explains the fee’s purpose, and compares the fee to those charged at other Western Canadian Universities. University of Lethbridge STUDENT FEE REPORT – 2004-05 Table of Contents Executive Summary Pg Glossary of Fees Pg Fee Descriptions Pg Analysis Table 1: Student Budget Analysis Table Pg Student Budget Analysis Pg Graph 1: Sample Student Budgets Pg Table 2: Fee Comparison 1994-2005 Pg University Revenue Analysis Pg Table 3: Tuition Revenue Pg Graph 2: % Difference Revenue Analysis Pg Graph 3: U of L Tuition Fees (1993/94-2003/04) Pg Table 4: Revenues Pg Graph 4: Revenue Distribution (%) Pg Graph 5: Revenue Distribution ($) Pg Table 5: Revenue Analysis Pg Graph 6: % Changes in Enrolment, etc. -

2015–2016 Academic Calendar Macewan University

2015–2016 Academic Calendar MacEwan University MacEwan University • 2015–2016 A C A D E M I C C A L E N D A R • MacEwan.ca 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION APPLIED DEGREE PROGRAMS 4 2015–2016 Academic Schedule 95 Bachelor of Applied Business Administration – 5 2015–2016 Holidays Observed Accounting 6 University Pillars 97 Bachelor of Applied Communications in Professional 6 Positioning Statement Writing – suspended 6 Educational Philosophy Statement 98 Bachelor of Applied Human Service Administration 6 Educational Goals POST-DIPLOMA CERTIFICATE PROGRAMS 7 Campus Locations 101 Cardiac Nursing Post-basic Certificate 8 Phone Directory 102 Perioperative Nursing for Registered Nurses REGISTRARIAL INFORMATION 104 Post-basic Nursing Practice 11 Admissions and Transfer 106 Wound Management Post-basic Certificate 20 Enrolment UNIVERSITY TRANSFER PROGRAMS 21 Student Records and Transcripts 109 Bachelor of Physical Education Transfer 24 Fees 111 Bachelor of Science in Engineering Transfer 29 Educational Funding, Scholarships and Awards 30 International Students CERTIFICATE AND DIPLOMA PROGRAMS 32 Institutional Graduation Regulations 114 Accounting and Strategic Measurement 32 Policies 117 Acupuncture 120 Arts and Cultural Management SERVICES FOR STUDENTS 123 Asia Pacific Management 34 Aboriginal Education Centre 125 Business Management 34 Alumni Status 131 Correctional Services 34 Child Care Centre 133 Design Studies 34 Library 137 Design Studies (3 majors)– suspended 34 MacEwan Athletics 140 Disability Management in the Workplace 34 MacEwan Bookstores 142 -

In Times of Crisis, We Can Come Together to Find Solutions

Spring 2020 finding solutions davidsuzuki.org In times of crisis, we can come together to find solutions We’re living in extraordinary times. I’m writing these Before the pandemic, we saw youth rise all over the lines to you from my home, without knowing the future, world, and a human tide of more than a million people practising physical distancing and adhering to the best march throughout Canada. It was a magnificent show of advice about coping with COVID-19. solidarity with the promise of a new world. We are all experiencing a heightened sense of fear and No doubt, this promise is still alive. Because on the other uncertainty. But we also feel hope and resilience, and we side of the health, financial and economic crises, we’ll see communities coming together in unprecedented ways. still have to respond to the climate emergency. We did not choose to be faced with these huge challenges and we will Our hearts go out to those directly affected by this sometimes be tempted to give in to discouragement. But global pandemic. And our deepest gratitude is to the we will not give in, because together we will succeed. professionals working tirelessly on the front lines to try and keep everyone healthy and safe. Thank you. On the other side of the COVID-19 crisis, we will have gained confidence in our ability to unite when emergency Thank you also to the everyday heroes reaching out to requires it and mobilize our efforts toward a common goal. vulnerable people in their families and communities and Isn't that exactly what we need to do to respond to the offering support, friendship and compassion. -

David Suzuki Foundation's

David Suzuki at WORK Copyright © 2009 David Suzuki Foundation ISBN 978-1-897375-27-3 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data for this publication is available through the National Library of Canada. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank Great-West Life for becoming the first national supporter of the David Suzuki at Work program. The authors wish to thank the following individuals and organizations for their participation in the focus group that seeded ideas for this toolkit: Gayle Hadfield; Eric Randall, Next Level Games; Anne Stobart, Emily Carr University of Art & Design; and Henry Stoch, Deloitte. Some of their experiences are included here as case histories. Other case histories were adapted from Doing Business in a New Climate: A Guide to Measuring, Reducing and Offsetting Greenhouse Gas Emissions, a David Suzuki Foundation publication by Deborah Carlson and Paul Lingl. Special thanks to Mountain Equipment Coop for inspiration on the Dumpster Dive initiative and Working Design for the graphics on the original toolkit. We also thank, from the David Suzuki Foundation: Ashley Arden, Nelson Agustín, Lindsay Coulter, Lana Gunnlaugson, Katie Harper, Calvin Jang, Randi Kruse, Kim Lai, Nina Legac, Katie Loftus, Gail Mainster, Akua Schatz, Aryne Sheppard and Kim Vickers. DESIGN TITLE DESIGN Nelson Agustín Erika Rathje PHOTOGRAPHS iStockphoto Nelson Agustín (cover two upper right, pp 19 bottom, 25, 32, 49) College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta (p 23) Creative Commons http://www.flickr.com/photos/jillslivingroom/2404296545/ Deloitte (p 28 bottom) Kent Kallberg (pp 3, 4) Linda Mackie (cover lower right, pp 11, 28 upper right, 33, 52, 54, 56, 57, 61) Brooke McDonald (p 54 top) You are invited to provide feedback on Next Level Games (p 16 top) this toolkit, and share your success and Erika Rathje (p 59) challenges with greening your workplace by emailing [email protected].