Observations on the Nesting of Crabro Tenuis (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changes in the Insect Fauna of a Deteriorating Riverine Sand Dune

., CHANGES IN THE INSECT FAUNA OF A DETERIORATING RIVERINE SAND DUNE COMMUNITY DURING 50 YEARS OF HUMAN EXPLOITATION J. A. Powell Department of Entomological Sciences University of California, Berkeley May , 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY OF EXPLOITATION 4 HISTORY OF ENTOMOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS 7 INSECT FAUNA 10 Methods 10 ErRs s~lected for compar"ltive "lnBlysis 13 Bio1o~ica1 isl!lnd si~e 14 Inventory of sp~cies 14 Endemism 18 Extinctions 19 Species restricted to one of the two refu~e parcels 25 Possible recently colonized species 27 INSECT ASSOCIATES OF ERYSIMUM AND OENOTHERA 29 Poll i n!ltor<'l 29 Predqt,.n·s 32 SUMMARY 35 RECOm1ENDATIONS FOR RECOVERY ~4NAGEMENT 37 ACKNOWT.. EDGMENTS 42 LITERATURE CITED 44 APPENDICES 1. T'lbles 1-8 49 2. St::ttns of 15 Antioch Insects Listed in Notice of 75 Review by the U.S. Fish "l.nd Wildlife Service INTRODUCTION The sand dune formation east of Antioch, Contra Costa County, California, comprised the largest riverine dune system in California. Biogeographically, this formation was unique because it supported a northern extension of plants and animals of desert, rather than coastal, affinities. Geologists believe that the dunes were relicts of the most recent glaciation of the Sierra Nevada, probably originating 10,000 to 25,000 years ago, with the sand derived from the supratidal floodplain of the combined Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. The ice age climate in the area is thought to have been cold but arid. Presumably summertime winds sweeping through the Carquinez Strait across the glacial-age floodplains would have picked up the fine-grained sand and redeposited it to the east and southeast, thus creating the dune fields of eastern Contra Costa County. -

Arquivos De Zoologia MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO

Arquivos de Zoologia MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO ISSN 0066-7870 ARQ. ZOOL. S. PAULO 37(1):1-139 12.11.2002 A SYNONYMIC CATALOG OF THE NEOTROPICAL CRABRONIDAE AND SPHECIDAE (HYMENOPTERA: APOIDEA) SÉRVIO TÚLIO P. A MARANTE Abstract A synonymyc catalogue for the species of Neotropical Crabronidae and Sphecidae is presented, including all synonyms, geographical distribution and pertinent references. The catalogue includes 152 genera and 1834 species (1640 spp. in Crabronidae, 194 spp. in Sphecidae), plus 190 species recorded from Nearctic Mexico (168 spp. in Crabronidae, 22 spp. in Sphecidae). The former Sphecidae (sensu Menke, 1997 and auct.) is divided in two families: Crabronidae (Astatinae, Bembicinae, Crabroninae, Pemphredoninae and Philanthinae) and Sphecidae (Ampulicinae and Sphecinae). The following subspecies are elevated to species: Podium aureosericeum Kohl, 1902; Podium bugabense Cameron, 1888. New names are proposed for the following junior homonyms: Cerceris modica new name for Cerceris modesta Smith, 1873, non Smith, 1856; Liris formosus new name for Liris bellus Rohwer, 1911, non Lepeletier, 1845; Liris inca new name for Liris peruanus Brèthes, 1926 non Brèthes, 1924; and Trypoxylon guassu new name for Trypoxylon majus Richards, 1934 non Trypoxylon figulus var. majus Kohl, 1883. KEYWORDS: Hymenoptera, Sphecidae, Crabronidae, Catalog, Taxonomy, Systematics, Nomenclature, New Name, Distribution. INTRODUCTION years ago and it is badly outdated now. Bohart and Menke (1976) cleared and updated most of the This catalog arose from the necessity to taxonomy of the spheciform wasps, complemented assess the present taxonomical knowledge of the by a series of errata sheets started by Menke and Neotropical spheciform wasps1, the Crabronidae Bohart (1979) and continued by Menke in the and Sphecidae. -

An Endosymbiotic Streptomycete in the Antennae of Philanthus Digger Wasps

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2006), 56, 1403–1411 DOI 10.1099/ijs.0.64117-0 ‘Candidatus Streptomyces philanthi’, an endosymbiotic streptomycete in the antennae of Philanthus digger wasps Martin Kaltenpoth,1 Wolfgang Goettler,1,2 Colin Dale,3 J. William Stubblefield,4 Gudrun Herzner,2 Kerstin Roeser-Mueller1 and Erhard Strohm2 Correspondence 1University of Wu¨rzburg, Department for Animal Ecology and Tropical Biology, Am Hubland, Martin Kaltenpoth D-97074 Wu¨rzburg, Germany martin.kaltenpoth@biozentrum. 2University of Regensburg, Department of Zoology, D-93040 Regensburg, Germany uni-wuerzburg.de 3University of Utah, Department of Biology, 257 South 1400 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA 4Fresh Pond Research Institute, 173 Harvey Street, Cambridge, MA 02140, USA Symbiotic interactions with bacteria are essential for the survival and reproduction of many insects. The European beewolf (Philanthus triangulum, Hymenoptera, Crabronidae) engages in a highly specific association with bacteria of the genus Streptomyces that appears to protect beewolf offspring against infection by pathogens. Using transmission and scanning electron microscopy, the bacteria were located in the antennal glands of female wasps, where they form dense cell clusters. Using genetic methods, closely related streptomycetes were found in the antennae of 27 Philanthus species (including two subspecies of P. triangulum from distant localities). In contrast, no endosymbionts could be detected in the antennae of other genera within the subfamily Philanthinae (Aphilanthops, Clypeadon and Cerceris). On the basis of morphological, genetic and ecological data, ‘Candidatus Streptomyces philanthi’ is proposed. 16S rRNA gene sequence data are provided for 28 ecotypes of ‘Candidatus Streptomyces philanthi’ that reside in different host species and subspecies of the genus Philanthus. -

Appendix 5: Fauna Known to Occur on Fort Drum

Appendix 5: Fauna Known to Occur on Fort Drum LIST OF FAUNA KNOWN TO OCCUR ON FORT DRUM as of January 2017. Federally listed species are noted with FT (Federal Threatened) and FE (Federal Endangered); state listed species are noted with SSC (Species of Special Concern), ST (State Threatened, and SE (State Endangered); introduced species are noted with I (Introduced). INSECT SPECIES Except where otherwise noted all insect and invertebrate taxonomy based on (1) Arnett, R.H. 2000. American Insects: A Handbook of the Insects of North America North of Mexico, 2nd edition, CRC Press, 1024 pp; (2) Marshall, S.A. 2013. Insects: Their Natural History and Diversity, Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY, 732 pp.; (3) Bugguide.net, 2003-2017, http://www.bugguide.net/node/view/15740, Iowa State University. ORDER EPHEMEROPTERA--Mayflies Taxonomy based on (1) Peckarsky, B.L., P.R. Fraissinet, M.A. Penton, and D.J. Conklin Jr. 1990. Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Northeastern North America. Cornell University Press. 456 pp; (2) Merritt, R.W., K.W. Cummins, and M.B. Berg 2008. An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, 4th Edition. Kendall Hunt Publishing. 1158 pp. FAMILY LEPTOPHLEBIIDAE—Pronggillled Mayflies FAMILY BAETIDAE—Small Minnow Mayflies Habrophleboides sp. Acentrella sp. Habrophlebia sp. Acerpenna sp. Leptophlebia sp. Baetis sp. Paraleptophlebia sp. Callibaetis sp. Centroptilum sp. FAMILY CAENIDAE—Small Squaregilled Mayflies Diphetor sp. Brachycercus sp. Heterocloeon sp. Caenis sp. Paracloeodes sp. Plauditus sp. FAMILY EPHEMERELLIDAE—Spiny Crawler Procloeon sp. Mayflies Pseudocentroptiloides sp. Caurinella sp. Pseudocloeon sp. Drunela sp. Ephemerella sp. FAMILY METRETOPODIDAE—Cleftfooted Minnow Eurylophella sp. Mayflies Serratella sp. -

Chemistry and Pharmacology of Solitary Wasp Venoms

5 Chemistry and Pharmacology of Solitary Wasp Venoms TOM PIEK and WILLEM SPANJER Farmacologisch Laboratorium Universiteit van Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands I. Introduction 161 II. Diversity of Solitary Wasp Venoms 162 A. Symphyta 162 B. Apocrita 164 III. Pharmacology of Solitary Wasp Venoms 230 A. Effects on Metabolism and Endocrine Control . 230 B. Neurotoxic Effects 234 IV. Conclusion 287 References 289 I. INTRODUCTION This chapter reviews our present knowledge on the pharmacology and chemistry of venoms produced by solitary wasps. Among the Hymenoptera that produce a venom the social wasps (Chapter 6), bees (Chapter 7) and ants (Chapter 9) are most familiar to men. The venoms of these social Hymenoptera are used by these insects for defending themselves and their colonies. These venoms produce pain and local damage in large vertebrates and are lethal to insects and small vertebrates. Multiple stings of bees, ants or wasps, as well as allergic reactions, may be responsible for killing larger vertebrates. Of all solitary wasps, only some bethylid species may attack humans (see Bethylioidea, Section II,B,3). In this discussion the term social wasps refers to members of the Vespinae, despite the fact that some wasps, while taxonomically included in solitary wasp families, display social or semi-social life. If, for example, hymenopteran social behaviour is simply defined by the activity of an individual benefiting the larvae of another individual of the same species, then the sphecid wasp Microstigmus comes must be qualified as a social wasp (Matthews, 1968). If sociality is the condition shown by species in which there is division of labour, then the guarding behaviour of males of the sphecid Tachytes 161 VENOMS OF THE HYMENOPTERA Copyright © 1986 by Academic Press Inc. -

American Entomology, Or Descriptions of the Insects of North

) fl' ,- ^7 7 ENTOMOLOGY, BeioictftftConsi V ( i_ 1 B R A R , INSECTS OF NORTH AMERICA. ILLUSTRATED BY COLOURED FIGURES ORIGINAL DRAWINGS EXECUTED FROM NATURE. BY THOMAS SAY, Curator of ihe American Philosophical Society, and of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia ; Correspondent of the Philomathique Society of Paris ; and Professor of Natural History in the University of Pennsylvania, and of Zoology in the Philadelphia Museum. ^^..._„__ --» " Each moss, Each shell, each crawling insect, holds a rank Important in the plan of Him who fram'd This scale of beings." STILHNGFLIET. PUBLISHED BY SAMUEL AUGUSTUS MITCHELL. FOR SALE BY ANTHONY FINLET, CORNER OF FOURTH AND CHESNUT 8T. William Brown, Printer. 1824. TO MACLURE, WILLIAM , PRESIDENT OF THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES OF PHILADELPHIA, AND OF THE AMERICAN GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, &c. &c. Distinguished as a successful cultivator, and munificent patron, of the Natural Sciences, this Work is respectfully inscribed, By his much obliged, and most obedient serv^ant, THE AUTHOR. " As there is no part of nature too mean for the Divine Pre- sence; so there is no kind of subject, having its foundation in nature, that is below the dignity of a philosophical inquiry." Harris. IPtr(f;»re The author's design, in the present work, is to exemplify the genera and species of the in- sects of the United States, by means of coloured engravings. He enters upon the task without any expectation of pecuniary remuneration, and fully aware of the many obstacles by which he must inevitably be opposed. The graphic execution of the work will ex- hibit the present state of the arts in this country, as applied to this particular department of natural science, as no attention will be wanting, in this respect, to render the work worthy of the encou- ragement of the few who have devoted a portion of their attention to animated nature. -

Phd Thesis, University of Würzburg

Protective bacteria and attractive pheromones Symbiosis and chemical communication in beewolves (Philanthus spp., Hymenoptera, Crabronidae) Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Martin Kaltenpoth aus Hagen Würzburg 2006 Eingereicht am: ………………………………………………………………….…….………..… Mitglieder der Promotionskommission: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Martin J. Müller Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Erhard Strohm Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Roy Gross Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: ………………………………………………….………….….. Doktorurkunde augehändigt am: …………………………………………….…………………… 2 “We are symbionts on a symbiotic planet, and if we care to, we can find symbiosis everywhere.” Lynn Margulis, “Symbiotic Planet” (1998) “There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.” Douglas Adams, “The Restaurant at the End of the Universe” (1980) 3 4 CONTENTS LIST OF PUBLICATIONS..................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1: GENERAL INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 9 1.1 Symbiosis ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.1.1 Insect-bacteria symbiosis..................................................................................... -

Great Lakes 'Entomologist

Vol. 23, No. 2 Summer 1990 THE GREAT LAKES 'ENTOMOLOGIST PUBLISHED BY 'THE MICHIGAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY· THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Volume 23 No.2 ISSN 0090-0222 TABI,E OF CONTENTS Late summer-fall solitary wasp fauna of central New York (Hymenoptera: Tiphiidae, Pompilidae, Sphecidae) Frank E. Kurczewski and Robert E. Acciavatti .................................57 Aggregation behavior of a willow flea beetle, Altica subplicata (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) Catherine E. Bach and Deborah S. Carr .......................................65 Gyrinidae of Wisconsin, with a key to adults of both sexes and notes on distribution and habitat William L. Hilsenhoff ......................................................77 Parasitoids of Chionaspis pinifoliae (Homoptera: Diaspididae) in Iowa Daniel L. Burden and Elwood R. Hart ........................................93 Eastern range extension of Leptoglossus occidentalis with a key to Leptoglossus species o( America north of Mexico (Heteroptera: Coreidae) l.E. McPherson, R.l. Packauskas, S.l. Taylor, and M.F. O'Brien ................99 Seasonal flight patterns of Hemiptera (excluding Miridae) in a southern Illinois black walnut plantation l.E. McPherson and B.C. Weber ............................................105 COVER ILLUSTRATION Calopteryx maculata Beauv. (Odonata: Calopterygidae). Photograph by G.W. Bennett THE MICHIGAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY 1989-1990 OFFICERS President Richard J. Suider President-Elect Eugene Kenaga Executive Secretary M.C. Nielsen Journal Editor Mark F. O'Brien Newsletter Editor Robert Haack The Michigan Entomological Society traces its origins to the old Detroit Entomological Society and was organized on 4 November 1954 to "...promote the science of entomology in all its branches and by all feasible means, and to advance cooperation and good fellowship among persons interested in entomology." The Society attempts to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information in both amateur and professional circles, and encourages the study of insects by youth. -

Proquest Dissertations

COLONIZATION OF RESTORED PEATLANDS BY INSECTS: DIPTERA ASSEMBLAGES IN MINED AND RESTORED BOGS IN EASTERN CANADA Amélie Grégoire Taillefer Department ofNatural Resource Sciences McGill University, Montreal August 2007 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science ©Amélie Grégoire Taillefer, 2007 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Bran ch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51272-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-51272-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Sphecos: a Forum for Aculeate Wasp Researchers

SPHECOS Number 5 - February 1982 A Newsletter for Aculeate Wasp Researchers Arnold S. Menke, editor Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA c/o u. s. National Museum of Natural History Washington DC 20560 Notes from the Editor This issue of Sphecos is coming to you later than planned. Your editor has been inundated with administrative matters and time has simply slipped by. Highlights of this issue involve news about people, some scientific notes, a few obituaries, some trip reports and of course the usual recent literature coverage which includes another of Robin Edwards 1 special vespoid sections. I want to take this opportunity to thank Helen Proctor for typing most of this newsletter for me. Thanks also go to LUdnri:l"a Kassianoff for translating some Russian titles into English, and to Yiau Min Huang for translating some Chinese titles into English. Judging by the comments received, the readership of Sphecos 4 enjoyed Eric Grissell's "profile" (p. 9) more than anything else in the issue. Congratulations Eric! Sphecos is gaining considerable recogn1t1on via reviews in journals. The most recent and most extensive being published in "Soviet Bibliography" for 1980, issue #6. The nearly 2 page lauditory review by I. Evgen'ev concludes with the statement "Sphecos [is] a highly useful publication for people around the world who study wasp biology and systematics" [Woj Pulawski generously translated the entire review for me into English]. Currently Sphecos is mailed to about 350 waspologists around the world. This figure includes a few libraries such as those at the BMNH, the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Leningrad, the Albany Museum, Grahamstown, and the Nederlandse Entomologische Vereniging, Amsterdam to list a sample. -

Marine Turtles- Environmentally Sensitive Species Environment

E n viron men t TO BAGO n ewsl etter Environment TOBAGO March 2014 nvironment TOBA- E GO (ET) is a non- government, non-profit, vol- unteer organisation , not Marine Turtles- Environmentally Sensitive Species subsidized by any one group, corporation or government Environment TOBAGO body. Founded in 1995, ET is a proactive advocacy group that On the 18th February the EMA (Environmental Management Authority) Biodi- campaigns against negative versity Council was reconstituted, to which Environment TOBAGO is a member. The environmental activities throughout Tobago. We first order was to declare environmentally sensitive species for Tobago (and Trinidad) achieve this through a variety which included five marine turtles and White-Tailed Sabre Winged Hummingbird which of community and environ- is endemic to Tobago. This article focuses of these sensitive marine species. mental outreach programmes. Planet Earth has been occupied by ancient creatures, long before man (homo Environment TOBAGO is sapiens) made their appearance. Marine turtles, air breathing reptiles, have been around funded mainly through grants for over 150 million years. These amazing creatures make sea journeys of 1000 to 1400 and membership fees. These funds go back into implement- miles every 2 years- traversing the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, before returning to their ing our projects. We are natal (beach of birth) beaches to nest; laying eggs 5 to 7 times during a 4 month period. grateful to all our sponsors rd over the years and thank In Trinidad & Tobago, we have become known as the place where the 3 largest them for their continued populations of nesting sea turtles in the world visit every year. -

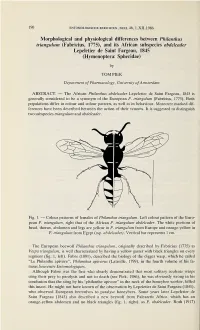

Morphological and Physiological Differences

190 ENTOMOLOGISCHE BERICHTEN, DEEL 46, 1.XII. 1986 Morphological and physiological differences between Philanthus triangulum (Fabricius, 1775), and its African subspecies abdelcader Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau, 1845 (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) by TOM PIEK Department of Pharmacology, University of Amsterdam ABSTRACT. — The African Philanthus abdelcader Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau, 1845 is generally considered to be a synonym of the European P. triangulum (Fabricius, 1775). Both populations differ in colour and colour pattern, as well as in behaviour. Moreover marked dif¬ ferences have been described between the action of their venoms. It is suggested to distinguish two subspecies triangulum and abdelcader. Fig. 1 — Colour patterns of females of Philanthus triangulum. Left colour pattern of the Euro¬ pean P. triangulum, right that of the African P. triangulum abdelcader. The white portions of head, thorax, abdomen and legs are yellow in P. triangulum from Europe and orange-yellow in P. triangulum from Egypt (ssp. abdelcader). Vertical bar represents 1 cm. The European beewolf Philanthus triangulum, originally described by Fabricius (1775) as Vespa triangulum, is well characterized by having a yellow gaster with black triangles on every segment (fig. 1, left). Fabre (1891), described the biology of the digger wasp, which he called “Le Philanthe apivore”, Philanthus apivorus (Latreille, 1799), in the fourth volume of his fa¬ mous Souvenirs Entomologiques. Although Fabre was the first who clearly demonstrated that most solitary aculeate wasps sting their prey to paralysis and not to death (see Piek, 1986), he was obviously wrong in his conclusion that the sting by his “philanthe apivore" in the neck of the honeybee worker, killed this insect.