Status Report from the American Acne & Rosacea Society On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compositions Comprising Drospirenone Molecularly

(19) & (11) EP 1 748 756 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61K 9/00 (2006.01) A61K 9/107 (2006.01) 29.04.2009 Bulletin 2009/18 A61K 9/48 (2006.01) A61K 9/16 (2006.01) A61K 9/20 (2006.01) A61K 9/14 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 05708751.2 A61K 9/70 A61K 31/565 (22) Date of filing: 10.03.2005 (86) International application number: PCT/IB2005/000665 (87) International publication number: WO 2005/087194 (22.09.2005 Gazette 2005/38) (54) COMPOSITIONS COMPRISING DROSPIRENONE MOLECULARLY DISPERSED ZUSAMMENSETZUNGEN AUS DROSPIRENON IN MOLEKULARER DISPERSION DES COMPOSITIONS CONTENANT DROSPIRENONE A DISPERSION MOLECULAIRE (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR • FUNKE, Adrian HU IE IS IT LI LT LU MC NL PL PT RO SE SI SK TR D-14055 Berlin (DE) Designated Extension States: • WAGNER, Torsten AL BA HR MK YU 13127 Berlin (DE) (30) Priority: 10.03.2004 EP 04075713 (74) Representative: Wagner, Kim 10.03.2004 US 551355 P Plougmann & Vingtoft a/s Sundkrogsgade 9 (43) Date of publication of application: P.O. Box 831 07.02.2007 Bulletin 2007/06 2100 Copenhagen Ø (DK) (60) Divisional application: (56) References cited: 08011577.7 / 1 980 242 EP-A- 1 260 225 EP-A- 1 380 301 WO-A-01/52857 WO-A-20/04022065 (73) Proprietor: Bayer Schering Pharma WO-A-20/04041289 US-A- 5 569 652 Aktiengesellschaft US-A- 5 656 622 US-A- 5 789 442 13353 Berlin (DE) Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Ocps) Used in the NM Family Planning Program (FPP

The following slides are intended to familiarize nurses and clinicians with oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) used in the NM Family Planning Program (FPP). The FPP does not intend for this information to supersede the Family Planning Protocol particularly on the requirement for Public Health Nurses in the Public Health Offices to consult a clinician as stated in the Protocol when in doubt or if it is necessary to switch the client’s OCP type. 1 2 Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) contain two hormones; estrogen and progestin. In general, any combined OCP is good for most women who are eligible to take estrogen according to the CDC U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC). Once again, refer to the US MEC chart to find out if OCP is a suitable choice for clients with specific health conditions. To learn a little bit about what each hormone does, the FPP is providing the following summary: Estrogen: provides endometrial stability = menstrual cycle control. A higher estrogen dose increases the venous thromboembolism (VTE) or clot risk but OCP clot risk is still less harmful than the clot risk related to pregnancy and giving birth. Progestin: provides most of the contraceptive effect by ‐Preventing luteinizing hormone (LH) surge /ovulation ‐Thickening the cervical mucus to prevent sperm entry. Two major OCP formations are available. Monophasic: There is only one dose of estrogen and progestin in each active pill in the packet; and Multiphasic: There are varying doses of hormones, particularly progestin in the active pills. 3 Section 3 of the FPP Protocol contains the OCP Substitute Table, which groups OCPs into 6 classes according to the estrogen dosage, the type of progestin and the formulations. -

Endocrinology 12 Michel Faure, Evelyne Drapier-Faure

Chapter 12 Endocrinology 12 Michel Faure, Evelyne Drapier-Faure Key points 12.1 Introduction Q HS does not generally appear to be In 1986 Mortimer et al. [14] reported that hi- associated with signs of hyperan- dradenitis suppurativa (HS) responded to treat- drogenism ment with the potent antiandrogen cyproterone acetate. They suggested that the disease could Q Sex hormones may affect the course of be androgen-dependent [8]. This hypothesis HS indirectly through, for example, was also upheld by occasional reports of women their effects on inflammation with HS under antiandrogen therapy [18]. Actu- ally, the androgen dependence of HS (similarly Q The role of end-organ sensitivity to acne) is only poorly substantiated. cannot be excluded at the time of writing 12.2 Hyperandrogenism and the Skin Q The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in HS has not been system- Androgen-dependent disorders encompass a atically investigated broad spectrum of overlapping entities that may be related in women to the clinical consequenc- es of the effects of androgens on target tissues and of associated endocrine and metabolic dys- functions, when present. #ONTENTS 12.1 Introduction ...........................95 12.2.1 Androgenization 12.2 Hyperandrogenism and the Skin .........95 12.2.1 Androgenization .......................95 One of the less sex-specific effects of androgens 12.2.2 Androgen Metabolism ..................96 12.2.3 Causes of Hyperandrogenism ...........96 is that on the skin and its appendages, and in particular their action on the pilosebaceous 12.3 Lack of Association between HS unit. Hirsutism is the major symptom of hyper- and Endocrinopathies ..................97 androgenism in women. -

Comparing the Effects of Combined Oral Contraceptives Containing Progestins with Low Androgenic and Antiandrogenic Activities on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis In

JMIR RESEARCH PROTOCOLS Amiri et al Review Comparing the Effects of Combined Oral Contraceptives Containing Progestins With Low Androgenic and Antiandrogenic Activities on the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Mina Amiri1,2, PhD, Postdoc; Fahimeh Ramezani Tehrani2, MD; Fatemeh Nahidi3, PhD; Ali Kabir4, MD, MPH, PhD; Fereidoun Azizi5, MD 1Students Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 2Reproductive Endocrinology Research Center, Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 3School of Nursing and Midwifery, Department of Midwifery and Reproductive Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 4Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran 5Endocrine Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic Of Iran Corresponding Author: Fahimeh Ramezani Tehrani, MD Reproductive Endocrinology Research Center Research Institute for Endocrine Sciences Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences 24 Parvaneh Yaman Street, Velenjak, PO Box 19395-4763 Tehran, 1985717413 Islamic Republic Of Iran Phone: 98 21 22432500 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Different products of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) can improve clinical and biochemical findings in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) through suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Objective: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to compare the effects of COCs containing progestins with low androgenic and antiandrogenic activities on the HPG axis in patients with PCOS. -

Hair Depilation for Hirsutism

Hair Depilation for Hirsutism Policy NHS NWL CCGs will fund facial hair depilation only when the following criteria are met: Facial There is an existing endocrine medical condition and severe facial hirsutism Ferriman Gallwey Score of 3 or more per area requested Medical treatments such as hormone suppression therapy has been tried for at least one year and failed. Patients with a BMI>30 should be in a weight reduction programme and should at least 5% of their body weight. Peri Anal Removal of excess hairs in the peri anal area will only be funded as part of treatment for pilonidal sinuses. Other Area Have undergone reconstructive surgery leading to abnormally located hair- bearing skin Laser treatment for excess hair (hirsutism) will only be funded for 6 treatment sessions and only at NHS commissioned services. Hair depilation for sites other than the above is not routinely funded and may be available via the IFR route under exceptional circumstances. These polices have been approved by the eight Clinical Commissioning Groups in North West London (NHS Brent CCG, NHS Central London CCG, NHS Ealing CCG, NHS Hammersmith and Fulham CCG, NHS Harrow CCG, NHS Hillingdon CCG, NHS Hounslow CCG and NHS West London CCG). Background Hirsutism is excessive hair growth in women in areas of the body where only to develop coarse hair, primarily on the face and neck area.1 Unwanted and excessive hair growth is a common problem and considerable amounts of time and money are spent on hair removal. It affects about 5-10% of women, and is often quoted as a cause of emotional distress. -

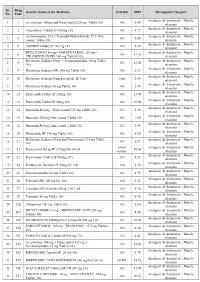

PMBJP Product.Pdf

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Metformin for the Treatment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a Little Help Along the Way

DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04668.x JEADV ORIGINAL ARTICLE Metformin for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a little help along the way R. Verdolini,† N. Clayton,‡,* A. Smith,‡ N. Alwash,† B. Mannello§ †Department of Dermatology, Princess Alexandra Hospital NHS trust, Harlow, Essex, and ‡Department of Dermatology, The Royal London Hospital, London, UK §Mannello Statistics, Via Rodi, Ancona, Italy *Correspondence: N. Clayton. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Background Despite recent insights into its aetiology, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) remains an intractable and debilitating condition for its sufferers, affecting an estimated 2% of the population. It is characterized by chronic, relapsing abscesses, with accompanying fistula formation within the apocrine glandbearing skin, such as the axillae, ano-genital areas and breasts. Standard treatments remain ineffectual and the disease often runs a chronic relapsing course associated with significant psychosocial trauma for its sufferers. Objective To evaluate the clinical efficacy of Metformin in treating cases of HS which have not responded to standard therapies. Methods Twenty-five patients were treated with Metformin over a period of 24 weeks. Clinical severity of the disease was assessed at time 0, then after 12 weeks and finally after 24 weeks. Results were evaluated using Sartorius and DLQI scores. Results Eighteen patients clinically improved with a significant average reduction in their Sartorius score of 12.7 and number of monthly work days lost reduced from 1.5 to 0.4. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI) also showed a significant improvement in 16 cases, with a drop in DLQI score of 7.6. -

Us Anti-Doping Agency

2019U.S. ANTI-DOPING AGENCY WALLET CARDEXAMPLES OF PROHIBITED AND PERMITTED SUBSTANCES AND METHODS Effective Jan. 1 – Dec. 31, 2019 CATEGORIES OF SUBSTANCES PROHIBITED AT ALL TIMES (IN AND OUT-OF-COMPETITION) • Non-Approved Substances: investigational drugs and pharmaceuticals with no approval by a governmental regulatory health authority for human therapeutic use. • Anabolic Agents: androstenediol, androstenedione, bolasterone, boldenone, clenbuterol, danazol, desoxymethyltestosterone (madol), dehydrochlormethyltestosterone (DHCMT), Prasterone (dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA , Intrarosa) and its prohormones, drostanolone, epitestosterone, methasterone, methyl-1-testosterone, methyltestosterone (Covaryx, EEMT, Est Estrogens-methyltest DS, Methitest), nandrolone, oxandrolone, prostanozol, Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (enobosarm, (ostarine, MK-2866), andarine, LGD-4033, RAD-140). stanozolol, testosterone and its metabolites or isomers (Androgel), THG, tibolone, trenbolone, zeranol, zilpaterol, and similar substances. • Beta-2 Agonists: All selective and non-selective beta-2 agonists, including all optical isomers, are prohibited. Most inhaled beta-2 agonists are prohibited, including arformoterol (Brovana), fenoterol, higenamine (norcoclaurine, Tinospora crispa), indacaterol (Arcapta), levalbuterol (Xopenex), metaproternol (Alupent), orciprenaline, olodaterol (Striverdi), pirbuterol (Maxair), terbutaline (Brethaire), vilanterol (Breo). The only exceptions are albuterol, formoterol, and salmeterol by a metered-dose inhaler when used -

Downloaded 9/24/2021 7:05:26 PM

Environmental Science Processes & Impacts PAPER View Article Online View Journal | View Issue Solid-phase extraction as sample preparation of water samples for cell-based and other in vitro Cite this: Environ. Sci.: Processes Impacts,2018,20,493 bioassays† a bc d b Peta A. Neale, Werner Brack, Selim A¨ıt-A¨ıssa, Wibke Busch, ef b d Juliane Hollender, Martin Krauss, Emmanuelle Maillot-Marechal,´ Nicole A. Munz,ef Rita Schlichting,b Tobias Schulze, b Bernadette Voglere and Beate I. Escher *abg In vitro bioassays are increasingly used for water quality monitoring. Surface water samples often need to be enriched to observe an effect and solid-phase extraction (SPE) is commonly applied for this purpose. The applied methods are typically optimised for the recovery of target chemicals and not for effect recovery for bioassays. A review of the few studies that have evaluated SPE recovery for bioassays showed a lack of experimentally determined recoveries. Therefore, we systematically measured effect recovery of a mixture of 579 organic chemicals covering a wide range of physicochemical properties that were spiked into a pristine water sample and extracted using large volume solid-phase extraction (LVSPE). Assays indicative of activation of xenobiotic metabolism, hormone receptor-mediated effects and adaptive stress responses were applied, with non-specificeffects determined through cytotoxicity measurements. Overall, effect recovery was found to be similar to chemical recovery for the majority of bioassays and LVSPE blanks had no effect. Multi-layer SPE exhibited greater recovery of spiked chemicals compared to LVSPE, but the blanks triggered cytotoxicity at high enrichment. Chemical recovery data together with single chemical effect data were used to retrospectively estimate with reverse recovery modelling that there was typically Received 19th November 2017 less than 30% effect loss expected due to reduced SPE recovery in published surface water monitoring Accepted 15th February 2018 studies. -

Desogestrel-Only Pill (Cerazette)

J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care: first published as 10.1783/147118903101197593 on 1 July 2003. Downloaded from Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care Clinical Effectiveness Unit A unit funded by the FFPRHC and supported by the University of Aberdeen and SPCERH to provide guidance on evidence-based practice New Product Review (April 2003) Desogestrel-only Pill (Cerazette) Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 2003; 29(3): 162–164 Evidence from a randomised trial has shown that a 75 mg (microgrammes) desogestrel pill inhibits ovulation in 97% of cycles. Thus, on theoretical grounds, we would expect the desogestrel pill to be more effective than existing progestogen- only pills (POPs). However, Pearl indices from clinical trials comparing it to a levonorgestrel POP were not significantly different. Therefore an evidence-based recommendation cannot be made that the desogestrel pill is different from other POPs in terms of efficacy, nor that it is similar to combined oral contraception (COC) in this respect. An evidence-based recommendation can be made that the desogestrel-only pill is similar to other POPs in terms of side effects and acceptability. The desogestrel-only pill is not recommended as an alternative to COC in routine practice, but provides a useful alternative for women who require oestrogen-free contraception. In clinical trials: l Ovulation was inhibited in 97% of cycles at 7 and 12 months after initiation. l The Pearl index was 0.41 per 100 woman-years, which was not significantly different from a levonorgestrel-only pill. However, the trial providing these data was too small to detect a clinically important difference. -

Pharmaceuticals Appendix

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADITOPRIME 56066-63-8 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADRENALONE 99-45-6 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 AFALANINE 2901-75-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 AFLOQUALONE 56287-74-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 AFUROLOL 65776-67-2 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 AGANODINE 86696-87-9 ACEFURTIAMINE 10072-48-7 AKLOMIDE 3011-89-0 ACEFYLLINE CLOFIBROL 70788-27-1