University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón by BRUCE ISAACS

4.3 Reality Effects: The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón BY BRUCE ISAACS Between 2001 and 2013, Alfonso Cuarón, working in concert with long-time collaborator, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, produced several works that effectively modeled a signature disposition toward film style. After a period of measured success in Hollywood (A Little Princess [1995], Great Expectations [1998]), Cuarón and Lubezki returned to Mexico to produce Y Tu Mamá También (2001), a film designed as a low- budget, independent vehicle (Riley). In 2006, Cuarón directed Children of Men, a high budget studio production, and in March 2014, he won the Academy Award for Best Director for Gravity (2013), a film that garnered the praise of the American and European critical establishment while returning in excess of half a billion dollars worldwide at the box office (Gravity, Box Office Mojo). Lubezki acted as cinematographer on each of the three films.[1] In this chapter, I attempt to trace the evolution of a cinematographic style founded upon the “long take,” the sequence shot of excessive duration. Reality Effects Each of Cuarón’s three films under examination demonstrates a fixation on the capacity of the image to display greater and more complex indices of time and space, holding shots across what would be deemed uncomfortable durations in a more conventional mode of cinema. As Udden argues, Cuarón’s films are increasingly defined by this mark of the long take, “shots with durations well beyond the industry standard” (26-27). Such shots are “attention-grabbing spectacles,” displaying the virtuosity of the filmmaker over and above the requirement of narrative unfolding. -

American Road Movies of the 1960S, 1970S, and 1990S

Identity and Marginality on the Road: American Road Movies of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1990s Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies. © Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Abrégé …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Acknowledgements …..………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Chapter One: The Founding of the Contemporary Road Rebel …...………………………...… 23 Chapter Two: Cynicism on the Road …………………………………………………………... 41 Chapter Three: The Minority Road Movie …………………………………………………….. 62 Chapter Four: New Directions …………………………………………………………………. 84 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………………..... 90 Filmography ……………………………………………………………………………………. 93 2 Abstract This thesis examines two key periods in the American road movie genre with a particular emphasis on formations of identity as they are articulated through themes of marginality, freedom, and rebellion. The first period, what I term the "founding" period of the road movie genre, includes six films of the 1960s and 1970s: Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider (1969), Francis Ford Coppola's The Rain People (1969), Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Richard Sarafian's Vanishing Point (1971), and Joseph Strick's Road Movie (1974). The second period of the genre, what I identify as that -

Diciembreenlace Externo, Se Abre En

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 91 3691125 Fax: 91 4672611 (taquilla) [email protected] 91 369 2118 http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html (gerencia) Fax: 91 3691250 MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala diciembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2009 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.45 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico DICIEMBRE 2009 Monte Hellman Dario Argento Cine para todos - Especial Navidad Charles Chaplin (I) El nuevo documental iberoamericano 2000-2008 (I) La comedia cinematográfica española (II) Premios Goya (y V) El Goethe-Institut Madrid presenta: Ulrike Ottinger Buzón de sugerencias Muestra de cortometrajes de la PNR Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

On Anamorphic Adaptations and the Children of Men

ISSN 1751-8229 Volume Eleven, Number Two On Anamorphic Adaptations and the Children of Men Gregory Wolmart, Drexel University, United States Abstract In this article, I expand upon Slavoj Zižek’s “anamorphic” reading of Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men (2006). In this reading, Zižek distinguishes between the film’s ostensible narrative structure, the “foreground,” as he calls it, and the “background,” wherein the social and spiritual dissolution endemic to Cuaron’s dystopian England draws the viewer into a recognition of the dire conditions plaguing the post-9/11, post-Iraq invasion, neoliberal world. The foreground plots the conventional trajectory of the main character Theo from ordinary, disaffected man to self-sacrificing hero, one whose martyrdom might pave the way for a new era of regeneration. According to Zižek, in this context the foreground merely entertains, while propagating some well-worn clichés about heroic individualism as demonstrated through Hollywood’s generic conventions of an action- adventure/political thriller/science-fiction film. Zižek contends that these conventions are essential to the revelation of the film’s progressive politics, as “the fate of the individual hero is the prism through which … [one] see[s] the background even more sharply.” Zižek’s framing of Theo merely as a “prism” limits our understanding of the film by not taking into account its status as an adaptation of P.D. James’ The Children of Men (1992). This article offers such an account by interpreting the differences between the film and its literary source as one informed by the transition from Cold War to post-9/11 neoliberal conceptions of identity and politics. -

![1934-11-30 [P C-6]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0667/1934-11-30-p-c-6-700667.webp)

1934-11-30 [P C-6]

assigned by Paramount to write RUSSIAN in Dietrich's next film. Which doesn't Back to Pioneer Days Best-Dressed Film Girls look as If that company expected her MALE Columbia's New Film to leave it, as has been rumored. CHORUS Other rumors are to the effect that Film Wheels' Classified for Directors Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer is testing Rosa- Story,'Wagon mund Plnchot for a part in "The Good Earth," though she is supposed to be scheduled to appear in "The «eat· BSc. SI.10. Sl.SS. Sî.tn. Mrs. Some Hard Fighting and Riding in New Picture Committee Will Select Smartest-Looking Extras •Brave Live On." Porter » (Dr—»·«)■ IMP Gi NA. 71St (Copyright. 1934, by the North American CeneUtntl·· Ball· Tact· 4:40 f. a. at the Metropolitan—The Star's Santa to Receive More Money for Appearing Newspaper Alliance, Inc.) in Claus Expedition by Plane. Society Scenes. Mammoth School of Fish. World-famous Vlellnlat. TAMPA, Fla. OP).—Aviators flying S1.6S. S2.20, W.Î5. SS.S0. over the Gulf of Mexico recently Mrs. Dtmr'· (Or··»'·) WHEELS." film in the accepted manner, accomplish- BY MOLLIE MERRICK. ous casting men from the studios and isoo o. s "Τ TAGON sighted a school of kingfish extending able a hard- two fashion artists, as unan- Comtitotlon Ball. 8m.. Dm. ». 4 P.m. ol the hard only by clean-living, calif., November yet a front. It / saga fighting along 35-mile appeared Firit Tim· mt Per alar Price·: \/\ fighting son of the West. In so doing 30 (N.A.NA.).—One of the nounced. -

Activity Worksheets LEVEL 3 Teacher Support Programme

PENGUIN READERS Activity worksheets LEVEL 3 Teacher Support Programme Psycho Photocopiable While reading a ‘I’m sorry I wasn’t in the office.’ Chapters 1–3 ……………………………………………… 1 Answer these questions about Marion Crane. b ‘What an amusing young man.’ a How old is she? ……………………………………………… ……………………………………………… c ‘You can’t bring strange young girls up to this b What kind of work does she do? house.’ ……………………………………………… ……………………………………………… c Is she married? d ‘I made trouble for you. I’m sorry.’ ……………………………………………… ……………………………………………… d Is she a happy woman? Why? / Why not? e ‘A boy’s best friend is his mother.’ ……………………………………………… ……………………………………………… e Does she have any brothers or sisters? f ‘If you love someone, you don’t leave them.’ ……………………………………………… ……………………………………………… 2 Complete the sentences with the names from g ‘I made a bad mistake.’ the box. ……………………………………………… 5 Choose the right answer. Tommy Cassidy Marion Crane a Why does Marion stop at the motel? … Sam Loomis Mr Lowery the policeman 1 Because she doesn’t want to see the a ………………… wants to marry her policeman again. boyfriend. 2 Because she is tired and hungry. b ………………… needs $11,000 to pay his 3 Because she wants to call Sam. debts. b Why does Marion write the wrong name in c ………………… is late to work after lunch the visitor’s book? … but her boss is having lunch with a customer. 1 Because she and Sam meet secretly. d ………………… is an unpleasant man with 2 Because she always does. lots of money. 3 Because she doesn’t want the police to find e ………………… leaves work with $40,000. her. f ………………… sees Marion Crane in her c Where does Marion hide the money? … car at some traffic lights. -

Half Title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS in CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN

<half title>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS</half title> i Traditions in World Cinema General Editors Linda Badley (Middle Tennessee State University) R. Barton Palmer (Clemson University) Founding Editor Steven Jay Schneider (New York University) Titles in the series include: Traditions in World Cinema Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Jay Schneider (eds) Japanese Horror Cinema Jay McRoy (ed.) New Punk Cinema Nicholas Rombes (ed.) African Filmmaking Roy Armes Palestinian Cinema Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi Czech and Slovak Cinema Peter Hames The New Neapolitan Cinema Alex Marlow-Mann American Smart Cinema Claire Perkins The International Film Musical Corey Creekmur and Linda Mokdad (eds) Italian Neorealist Cinema Torunn Haaland Magic Realist Cinema in East Central Europe Aga Skrodzka Italian Post-Neorealist Cinema Luca Barattoni Spanish Horror Film Antonio Lázaro-Reboll Post-beur Cinema ii Will Higbee New Taiwanese Cinema in Focus Flannery Wilson International Noir Homer B. Pettey and R. Barton Palmer (eds) Films on Ice Scott MacKenzie and Anna Westerståhl Stenport (eds) Nordic Genre Film Tommy Gustafsson and Pietari Kääpä (eds) Contemporary Japanese Cinema Since Hana-Bi Adam Bingham Chinese Martial Arts Cinema (2nd edition) Stephen Teo Slow Cinema Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge Expressionism in Cinema Olaf Brill and Gary D. Rhodes (eds) French Language Road Cinema: Borders,Diasporas, Migration and ‘NewEurope’ Michael Gott Transnational Film Remakes Iain Robert Smith and Constantine Verevis Coming-of-age Cinema in New Zealand Alistair Fox New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas Dolores Tierney www.euppublishing.com/series/tiwc iii <title page>NEW TRANSNATIONALISMS IN CONTEMPORARY LATIN AMERICAN CINEMAS Dolores Tierney <EUP title page logo> </title page> iv <imprint page> Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. -

The Horror Within the Genre

Alfred Hitchcock shocked the world with his film Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), once he killed off Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) half way through the film. Her sister, Lila Crane (Vera Miles), would remain untouched even after Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) attacked her and her sisters lover. Unlike her sister, Lila did not partake in premarital sex, and unlike her sister, she survived the film. Almost 20 years later audiences saw a very similar fate play out in Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978). Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) managed to outlive her three friends on Halloween night. Once she slashed her way through Michael Myers (Nick Castle), Laurie would remain the lone survivor just as she was the lone virgin. Both Lila and Laurie have a common thread: they are both conventionally beautiful, smart virgins, that are capable of taking down their tormentors. Both of these women also survived a male murder and did so by fighting back. Not isolated to their specific films, these women transcend their characters to represent more than just Lila Crane or Laurie Strode—but the idea of a final girl, establishing a trope within the genre. More importantly, final girls like Crane and Strode identified key characteristics that contemporary audiences wanted out of women including appearance, morality, sexual prowess, and even femininity. While their films are dark and bloodstained, these women are good and pure, at least until the gruesome third act fight. The final girl is the constant within the slasher genre, since its beginning with films like Psycho and Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960). -

S • Homophones • One-Word Titles • Cool Beans • Landmark Addresses • Light the Way Multiple “A”S 1

Category Trivia August 2021 There are six categories with six questions in each category. The categories are: • Multiple “A” s • Homophones • One-Word Titles • Cool Beans • Landmark Addresses • Light the Way Multiple “A”s 1. What organization represents retired people, is a source of information on topics of interest to seniors, and offers many membership benefits? AARP It stands for American Association of Retired People. Multiple “A”s 2. What are the initials of the 12-step program for alcoholics? AA It stands for Alcoholics Anonymous. Multiple “A”s 3. What are the letters for a two-year college degree? AA It stands for associate of arts. Some undergraduates earn an AA at a community college before completing the final two years of a bachelor’s degree at a four-year university. Multiple “A”s 4. What does NAACP stand for? National Association for the Advancement of Colored People It was founded in 1909, and it’s the largest and oldest civil rights organization in the United States. Multiple “A”s 5. What organization oversees college athletics? NCAA It stands for National Collegiate Athletic Association. Multiple “A”s 6. What is the highest bond rating? AAA Also known as investment-grade bonds, they are the safest bonds. Bonds rated CCC and below are considered junk bonds, and they pay the highest interest rate due to the possibility that investors may lose their entire investment. Homophones 7. What is your mother’s sister and an insect? Aunt/ant Homophones 8. What is an advertisement and how you arrive at a sum of numbers? Ad/add Today, advertisements come in many forms, from written copy to interactive videos. -

Children of Men

Children of Men Synopsis In 2027, as humankind faces the likelihood of its own extinction, a disillusioned government agent agrees to help transport and protect a miraculously pregnant woman to a sanctuary at sea where her child's birth may help scientists to save the future of mankind. Introduction This resource is aimed at students of Film and Media Studies and may be also of interest to English students in the consideration of genre. www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2007. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites. Studying Science Fiction Science fiction has, as one of its central conventional elements, the ‘What if…?’ question. For example, ‘What if aliens took over the world?’ This question is then played out during the narrative. Look at the list of sci-fi titles in the table below and think about the ‘What if…?’ questions that they deal with. Science fiction film ‘What if…?’ question Alien Bladerunner Transformers The Matrix War of the Worlds Brazil www.filmeducation.org 2 ©Film Education 2007. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites. Fact and Fiction Science fiction as a genre has its origins in Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein (written in 1831). The social context in which she wrote the novel are very significant as society was changing rapidly and science was making possible things that belonged in the realms of imagination. The relationship between scientific possibility and fiction formed the basis of a new kind of genre, which made the exploration of these potentially scary ‘What If…?’ questions possible. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

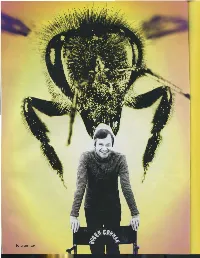

30 MENTAL FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA by IAN LENDLER

30 MENTAL_FLOSS • HOW ROGER CORMAN REVOLUTIONIZED Cl EMA BY IAN LENDLER MENTALFLOSS.COM 31 the Golden Age of Hollywood, big-budget movies were classy affairs, full of artful scripts and classically trained actors. And boy, were they dull. Then came Roger Corman, the King of the B-Movies. With Corman behind the camera, motorcycle gangs and mutant sea creatures .filled the silver screen. And just like that, movies became a lot more fun. .,_ Escape from Detroit For someone who devoted his entire life to creating lurid films, you'd expect Roger Corman's biography to be the stuff of tab loid legend. But in reality, he was a straight-laced workaholic. Having produced more than 300 films and directed more than 50, Corman's mantra was simple: Make it fast and make it cheap. And certainly, his dizzying pace and eye for the bottom line paid off. Today, Corman is hailed as one of the world's most prolific and successful filmmakers. But Roger Corman didn't always want to be a director. Growing up in Detroit in the 1920s, he aspired to become an engineer like his father. Then, at age 14, his ambitions took a turn when his family moved to Los Angeles. Corman began attending Beverly Hills High, where Hollywood gossip was a natural part of the lunchroom chatter. Although the film world piqued his interest Corman stuck to his plan. He dutifully went to Stanford and earned a degree in engineering, which he didn't particularly want. Then he dutifully entered the Navy for three years, which he didn't particularly enjoy.