West Virginia Andrew Graham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

List of Participants Adamovich, Igor Ohio State University [email protected] Aydil, Eray University of Minnesota [email protected] Babaeva, Natalia University of Michigan [email protected] Barnat, Ed SNLA [email protected] Bartis, Elliot University of Maryland [email protected] Bilik, Narula University of Minnesota [email protected] Boris, David Naval Research Laboratory [email protected] Cohen, Adam PPPL [email protected] Demidov, Vladimir West Virginia University [email protected]; [email protected] Donnelly, Vince University of Houston [email protected] Economou, Demetre University of Houston [email protected] Efthimion, Philip PPPL [email protected] Feldman, Uri Naval Research Laboratory [email protected] Finnegan, Sean DOE [email protected] Fox-Lyon, Nick University of Maryland [email protected] Franek, James West Virginia University [email protected] Galitzine, Cyril University of Michigan [email protected] Girshick, Steven University of Minnesota [email protected] Godyak, Valery University of Michigan [email protected] Graves, David UC-Berkeley [email protected] Gray, Robert EP Technologies [email protected] Hara, Kentaro University of Michigan [email protected] Hershkowitz, Noah University of Wisconsin [email protected] Hopwood, Jeffrey Tufts University [email protected] Joseph, Eric IBM [email protected] Kaganovich, Igor PPPL [email protected] Kawamura, Emi UC-Berkeley [email protected] Khrabrov, Alex PPPL [email protected] Koepke, Mark West Virginia University [email protected] Kolobov, Vladimir CFDRC/Univ. of Alabama [email protected] Kortshagen, Uwe University of Minnesota [email protected] 1 Kramer, Nicolaas University of Minnesota [email protected] Kushner, Mark J. -

J. Sebastian Leguizamon CV

Juan Sebastian Leguizamon January 2019 Western Kentucky University Phone: (270) 745 − 3970 Department of Economics Email:[email protected] Bowling Green, KY 42101 Professional Experience Western Kentucky University, Assistant Professor of Economics 2015 - Present Vanderbilt University, Senior Lecturer- Economics 2013 - 2015 Tulane University, Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow- Murphy Institute of Political Economy 2011- 2013 West Virginia University, Graduate RA- Bureau of Business and Economic Research 2006- 2008 Inter-American Development Bank, D.C., Intern Research Assistant Jan 2005 - May 2005 Other Academic Appointments • Associate Editor, Revista de Economia del Caribe (August 2008- Present) • Book Review Co-Editor, Review of Regional Studies (August 2012- January 2015) Education Ph.D., Economics, 2011 -West Virginia University M.A., Economics, 2008 -West Virginia University B.S., Economics (Summa Cum Laude), 2005 -Davis & Elkins College with an additional major in Management Information Systems (MIS) Fields of Interest State and Local Public Finance, Public Policy, and Regional Economics Citizenship Colombia, USA Peer-Reviewed Publications [1] “Party Cues, Political Trends, and Fiscal Interactions in the United States” Contemporary Economic Policy. Accepted (with Martin Montero-Kusevic) [2] “The Housing Crisis, Foreclosures, and Local Tax Revenues.” Regional Science and Urban Eco- nomics. 2018, Vol. 70 pp. 300-311 (with James Alm). [3] “Health Insurance Subsidies and the Expansion of an Implicit Marriage Penalty: A Regional Com- parison of Various Means-Tested Programs.” Applied Economics Letters. 2018, Vol. 25(2) pp.130-135. (with Susane Leguizamon). [4] “Inflation Volatility and Economic Growth in Bolivia: A Regional Analysis.” Macroeconomics and Finance in Emerging Market Economies. 2018, Vol. 11(1) pp. -

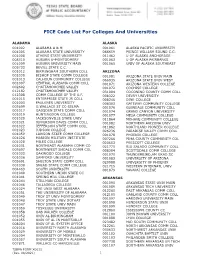

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

West Virginia University Athletics Brand Identity Brand Identity Vision

WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS BRAND IDENTITY BRAND IDENTITY VISION The objective of this exercise is to make sure that the brand is consistent across all applications and captures new audiences in an authentic and meaningful way. This guide outlines the evolution of the athletics brand and will serve as a reference resource for implementing the West Virginia University Athletics brand identity system. It will provide helpful guidelines that enable West Virginia Athletics staff, partners and suppliers to express the West Virginia Athletics brand effectively and appropriately across a wide range of applications and media. WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS BRAND IDENTITY 3 BRAND IDENTITY TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION ............................................................................... 3 BRAND OVERVIEW ............................................................ 5 PRIMARY IDENTITY FLYING WV MARK ............................................................. 7 COLOR PALETTE ...............................................................12 PRIMARY TYPEFACE .........................................................14 NUMERALS .......................................................................17 WORDMARKS ................................................................. 20 WEST VIRGINIA ........................................................... 22 MOUNTAINEERS .......................................................... 24 MONTANI SEMPER LIBERI ........................................... 26 SECONDARY IDENTITY SECONDARY TYPEFACE .................................................. -

Old Dominion University Board of Visitors April 27, 2017 2

AGENDA Old Dominion University Board of Visitors April 27, 2017 2 BOARD OF VISITORS OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Thursday, April 27, 2017, 8:30 a.m. Kate and John R. Broderick Dining Commons AGENDA I. Call to Order Carlton Bennett, Rector II. Resolution Approving 2017-2018 Operating Budget and Plan and Comprehensive Fee Proposal (pp. 5-6) Carlton Bennett, Rector III. Recess for Standing Committees Carlton Bennett, Rector IV. Reconvene Carlton Bennett, Rector V. Approval of Minutes – December 8, 2016 Meeting Carlton Bennett, Rector VI. Approval of Minutes – February 3, 2017 Board Retreat Carlton Bennett, Rector VII. Rector’s Report Carlton Bennett, Rector VIII. President's Report John R. Broderick, President IX. Reports of Standing Committees A. Audit Committee Frank Reidy, Vice Chair B. Academic and Research Advancement Committee Mary Maniscalco-Theberge, Chair 1. Tenure Recommendations (p. 7) 2. Award of Tenure to a Faculty Member (p. 8) 3. Approval of Faculty Representative to the Board of Visitors (p. 9) 4. Resolution Approving Dual Employment (p. 10) 3 Consent Agenda 5. Faculty Appointments (pp. 11-16) 6. Administrative Faculty Appointments (pp. 17-22) 7. Emeritus/Emerita Appointments (pp. 23-31) C. Administration and Finance Committee Ross Mugler, Presiding Chair D. Student Enhancement & Engagement Committee Jay Harris, Chair E. University Advancement Committee Frank Reidy, Chair X. Old/Unfinished Business Carlton Bennett, Rector XI. New Business Carlton Bennett, Rector XII. Adjourn Carlton Bennett, Rector 4 Return to Top RESOLUTION APPROVING 2017-2018 OPERATING BUDGET AND PLAN AND COMPREHENSIVE FEE PROPOSAL RESOLVED, that upon the recommendation of the President, the Board of Visitors approves the proposed expenditure plan in the University’s 2017-2018 Operating Budget and Plan and the corresponding 2017-2018 Comprehensive Fee Proposal. -

CARRIE B. LEE (Kerekes), Ph.D

CARRIE B. LEE (Kerekes), Ph.D. Associate Teaching Professor 285 Bellamy Building Department of Economics 113 Collegiate Loop College of Social Sciences and Public Policy Tallahassee, FL 32306 Florida State University E-mail: [email protected] Academic Positions 2018- Associate Teaching Professor of Economics, Florida State University 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Economics, Florida Gulf Coast University 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Economics, Florida Gulf Coast University 2007-2008 Charles G. Koch Doctoral Fellow, West Virginia University 2006-2007 Graduate Teaching Assistant, West Virginia University 2003-2004 2005-2006 Graduate Research Assistant, West Virginia University Education 2008 Ph.D. in Economics, West Virginia University 2006 M.A. in Economics, West Virginia University 2003 B.S. in Economics, minor in Spanish, West Virginia University, Magna Cum Laude Teaching Experience 2018- Florida State University, Undergraduate Courses: Principles of Microeconomics; Financial Markets, the Banking System, and Monetary Policy (honors) 2008-2018 Florida Gulf Coast University, Undergraduate Courses: Principles of Microeconomics, Principles of Macroeconomics, Intermediate Price Theory, Economic Development, Money and Capital Markets 2004-2007 West Virginia University, Undergraduate Courses: The Economic System, Principles of Microeconomics, Principles of Macroeconomics Academic Awards and Fellowships 2012 Best Research Paper Award 2011-2012, Lutgert College of Business, FGCU 2009 Young Scholars Fellow, Association of Private Enterprise Education 2007-2008 Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation Doctoral Fellow 2008 Young Scholars Fellow, Association of Private Enterprise Education 2007 Vickers Doctoral Student Teaching Award, West Virginia University 2007 Young Scholars Fellow, Association of Private Enterprise Education 2006 Earhart Fellow, Association of Private Enterprise Education 2005 Earhart Fellow, Association of Private Enterprise Education Journal Articles Kerekes, Carrie B. -

Dean Leonard C

ACADEMIC DEAN LEONARD C. NELSON COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND SCIENCES THE POSITION West Virginia University Institute of Technology (WVU Tech), part of the WVU system of campuses, is seeking an innovative, strategic, and dynamic leader to serve as the Dean of the Leonard C. Nelson College of Engineering and Sciences located in Beckley, West Virginia. RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE DEAN The Dean is the chief academic, fiscal, and administrative officer of the Leonard C. Nelson College of Engineering and Sciences and reports to the Campus Provost. He/she provides leadership for the faculty and articulates the College’s vision, qualities, and distinctiveness both within the University and to external constituencies. The Dean is responsible for curriculum planning and development, faculty and staff development, evaluation and budget administration. He/she is responsible for setting priorities and sustaining an environment of academic excellence. In order to be successful, the ideal candidate for the position of Dean of the Leonard C. Nelson College of Engineering and Sciences will: / Provide leadership and support for the College’s engineering and physical sciences programs / Promote the achievements of its students, faculty, and staff on a local, state, and national scale / Encourage and support faculty excellence in teaching, scholarship, and service / Ensure the integrity of program assessments and accreditation / Expand partnerships with businesses and other organizations in the local community to create opportunities for experiential learning -

West Virginia University at Parkersburg

WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY AT PARKERSBURG Financial Statements as of and for the Years Ended June 30, 2016 and 2015 and Independent Auditors’ Reports WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY AT PARKERSBURG TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 1 - 2 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS (RSI) (UNAUDITED) 3-15 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR YEARS ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 AND 2015: Statements of Net Position 16 Component Unit - WVU at Parkersburg Foundation, Inc. - Statements of Financial Position 17 Statements of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Net Position 18 Component Unit - WVU at Parkersburg Foundation, Inc. - Statements of Activities 19-20 Statements of Cash Flows 21-22 Notes to Financial Statements 23-60 REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION (RSI) 61 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT ON INTERNAL CONTROL OVER FINANCIAL 62-63 REPORTING AND ON COMPLIANCE AND OTHER MATTERS BASED ON AN AUDIT OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS PERFORMED IN ACCORDANCE WITH GOVERNMENT AUDITING STANDARDS CliftonLarsonAllen LLP CLAconnect.com INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT Board of Governors West Virginia University at Parkersburg Parkersburg, West Virginia Report on the Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying financial statements of West Virginia University at Parkersburg, a campus of the West Virginia Higher Education Policy Commission as of and for the year ended June 30, 2016 and 2015, and the related statements of revenue, expenses, and changes in net position, and cash flows for the years then ended, and the related notes to the financial statements, which collectively comprise -

1 JOYCE E. MCCONNELL J.D., LL.M. West

JOYCE E. MCCONNELL J.D., LL.M. West Virginia University Provost & Vice President for Academic Affairs Thomas R. Goodwin Professor of Law EXECUTIVE LEADERSHIP Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, West Virginia University, July 2014-present: As chief academic and budget officer, I serve as second on the leadership team of E. Gordon Gee, President of West Virginia University (WVU), a public flagship, land-grant, Carnegie Research 1 and Carnegie Engaged institution. My role is internal and external: As the academic and budget officer, I am responsible for campuses, colleges, centers, institutes, curriculum, students, faculty, research, libraries, facilities master planning, and outreach, including Extension. In my external role, I represent WVU with WV’s congressional delegation, governor, federal and state agencies, higher education institutions, legislature, business leaders, non- governmental organizations, communities, and alumni. In the recently completed $1.2 billion campaign, I partnered with the President Gee and the CEO of the WVU Foundation to build relationships with high-value donors, foundations, and corporations and personally achieved multi-million dollar gifts. Institution Description • WVU’s mission is threefold: provide excellent quality educational access and success; conduct research focused on meeting West Virginia’s and the world’s challenges; and, engage with West Virginia and the world to enhance prosperity, health and quality of life. • WVU has 28,000+ students split equally between resident and non-resident. Non- resident students are from all 50 states and 110 countries. • 21% of students are first-generation. • WVU offers 200+ degree programs on three campuses. • On main campus, there are 15 colleges: Agriculture, Arts and Sciences, Business and Economics, Creative Arts, Dentistry, Engineering, Education and Human Services, Honors, Law, Media, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Physical Activity and Sports Science, and Public Health. -

Michelle R. B Row N

Brown Michelle R. address] [Type your 76712 TX way Wood Drive, West Woodland 805 MICHELLE R. BROWN M VITA [email protected] Education: ICHELLE DATE SCHOOL DEGREE MAJOR Summers West Virginia University -- Education 1991 & 1990 Morgantown, West Virginia R. 1988 University of Kentucky M. A. Interior Design [Type your phone number] B Lexington, Kentucky ROWN 1986 Tennessee Technological University B. S. Home Economics Cookeville, Tennessee Interior Design 805Woodland West Dr. Wood SUMMERS East Tennessee State University -- Interior Design 1985 & 1987 Johnson City, Tennessee FALL 1982 - East Tennessee State University -- Home Economics [Type your e Spring 1984 Johnson City, Tennessee 254 Auxiliary Areas of Study: - 772 - Computer Aided Design (Auto CADD) - 1178 mail address]mail MS/DOS and Apple Macintosh Color Rendering way TX [email protected] edu H H 254 Business Classes: Accounting, Managerial Accounting, Essentials of Law, & Consumer Economics - Professional Experience: 710 - Senior Lecturer – Interior Design Baylor University 6260 O Family & Consumer Sciences Waco, Texas 2009 to Present 2014 to Present – ID Division Leader Lecturer – Interior Design Baylor University Family & Consumer Sciences Waco, Texas 2002 to 2009 Project Designer The Architect 2000 to 2002 Garden City, Kansas Senior Interior Designer Interiors 1995 to 2000 (Full Time) Morgantown, West Virginia Interior Designer 1990 to 1995 (Part Time) Assistant Professor West Virginia University Interior Design Morgantown, West Virginia 1988 to 1995 -

Old Dominion University Board of Visitors June 18, 2020 BOARD of VISITORS OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Emergency Meeting Thursday, June 18, 2020, 10:00 A.M

AGENDA Old Dominion University Board of Visitors June 18, 2020 BOARD OF VISITORS OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY Emergency Meeting Thursday, June 18, 2020, 10:00 a.m. AGENDA A. Call to Order Lisa Smith, Rector B. Approval of Minutes Lisa Smith, Rector 1. March 23, 2020 Emergency Meeting 2. April 23, 2020 Emergency Meeting 3. May 21, 2020 Special Emergency Meeting C. Ratification of Actions Taken by the Executive Committee Lisa Smith, Rector 1. Appointment of Head Football Coach – February 20, 2020 (p. 5) 2. Authorize President to Use Emergency Hire Process for Women’s Head Basketball Coach – April 16, 2020 (p. 6) D. Approval of Proposed 2020-2021 Tuition & Fees (p. 7) Greg DuBois, Vice President for Administration and Finance E. Enrollment Update and 2020-2021 Operating Budget and Plan Presentation (p. 8) Don Stansberry, Interim Vice President for Student Enhancement & Enrollment Services Greg DuBois, Vice President for Administration and Finance F. Rector’s Report Lisa Smith, Rector 1. Board of Visitors Budget Presentation Kay Kemper, Vice Rector G. President’s Report John R. Broderick, President H. Reports of Standing Committees 1. Academic and Research Advancement Committee Toykea Jones, Chair a. Dual Employment (p. 9) 2 Consent Agenda a. Faculty Appointments (pp. 10-12) b. Administrative Appointments (pp. 13-20) c. Emeritus and Emerita Appointments (pp. 21-35) Regular Agenda d. Proposed Revisions to the Policy on Reappointment/Annual Review or Nonreappointment of Faculty (pp. 36-40) e. Proposed Revisions to the Policy on Tenure (pp. 41-53) f. Proposed Revisions to the Policy on Promotion in Rank (pp. 54-62) g. -

Curriculum Vitae F. Carson Mencken Professor and Director of Graduate

Curriculum Vitae F. Carson Mencken Professor and Director of Graduate Studies Department of Sociology Baylor University One Bear Place Box 97326 Waco, TX 76798 Work: (254) 710-4863 Home: (254) 857-7727 email: [email protected] Education B.S. College of Charleston, SC (Sociology) 1987, summa cum laude M.A. Louisiana State University (Sociology) 1989 Ph.D. Louisiana State University (Sociology) 1994 Professional Positions Professor, Department of Sociology, Baylor University (6/2006 to present) Research Fellow, Center for Religious Inquiry Across the Disciplines, Baylor University Associate Editor, Rural Sociology, 2005-06. Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, Baylor University (8/2002 to 5/2006). Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Sociology, Baylor University (6/2004 to present). Chair, Division of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Applied Social Sciences, West Virginia University (6/1/2001-6/30/2002). Associate Professor of Sociology, Division of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Applied Social Sciences, West Virginia University (7/1/00-6/30/2002). Adjunct Associate Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics, College of Agriculture, Forestry and Consumer Sciences, West Virginia University (7/1/00-6/30/2002). Assistant Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, West Virginia University (8/94–6/00). Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, West Virginia University (8/96-8/00). Faculty Research Associate, Regional Research Institute, West Virginia University (5/95 to 6/30/02). Awards and Honors • 2005 GSA Outstanding Graduate Faculty Teaching Award, Baylor University • "Civic Engagement and County Economic Growth in Appalachia during the 1990s" Co- authored with Chris Bader and Clay Polson received the Southwestern Sociological Association Distinguished Paper Award for 2005.