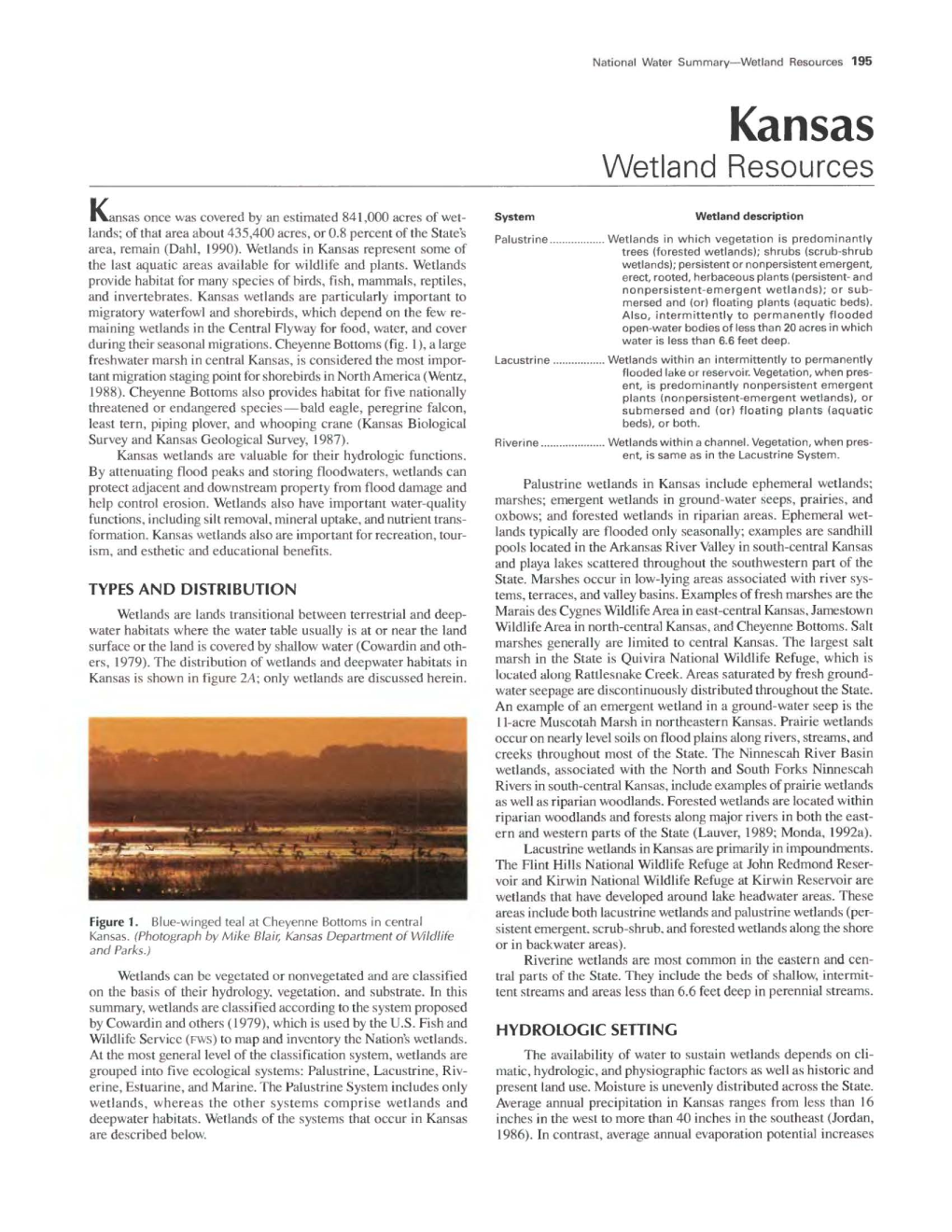

Kansas Wetland Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Kansas Severe Weather Awareness

2019 KANSAS SEVERE WEATHER AWARENESS Information Packet TORNADO SAFETY DRILL SEVERE WEATHER Tuesday, March 5, 2019 AWARENESS WEEK 10am CST/9am MST March 4-8, 2019 Backup Date: March 7, 2019 KANSAS SEVERE WEATHER AWARENESS WEEK MARCH 4-8, 2019 Table of Contents Page Number 2018 Kansas Tornado Overview 3 Kansas Tornado Statistics by County 4 Meet the 7 Kansas National Weather Service Offices 6 2018 Severe Summary for Extreme East Central and Northeast Kansas 7 NWS Pleasant Hill, MO 2018 Severe Summary for Northeast and East Central Kansas 9 NWS Topeka, KS 2018 Severe Summary for Central, South Central and Southeast Kansas 12 NWS Wichita, KS 2018 Severe Summary for North Central Kansas 15 NWS Hastings, NE 2018 Severe Summary for Southwest Kansas 17 NWS Dodge City, KS 2018 Severe Summary for Northwest Kansas 22 NWS Springfield, MO 2018 Severe Summary for Southeastern Kansas 23 NWS Goodland, KS Hot Spot Notifications 27 Weather Ready Nation 29 Watch vs. Warning/Lightning Safety 30 KANSAS SEVERE WEATHER AWARENESS WEEK MARCH 4-8, 2019 2 2018 Kansas Tornado Overview Tornadoes: 45 17 below the 1950-2018 average of 62 50 below the past 30 year average of 95 48 below the past 10 year average of 93 Fatalities: 0 Injuries: 8 Longest track: 15.78 miles (Saline to Ottawa, May 1, EF3) Strongest: EF3 (Saline to Ottawa, May 1; Greenwood, June 26) Most in a county: 9 (Cowley). Tornado days: 14 (Days with 1 or more tornadoes) Most in one day: 9 (May 2, May 14) Most in one month: 34 (May) First tornado of the year: May 1 (Republic Co., 4:44 pm CST, EF0 5.29 -

515 S. Kansas Ave., Suite 201 | Topeka, KS 66603 JAG-K MISSION

Dear Member of the House Education Committee, Thank you for the opportunity to discuss Jobs for America’s Graduates-Kansas (JAG-K). JAG-K is a 501(c)3 organization that invests in kids facing numerous obstacles to success. These are students generally not on track to graduate from high school, and, more than likely, headed for poverty or continuing in a generational cycle of poverty. JAG-K gives students hope for a better outcome. Incorporating a successful research-based model that was developed in Delaware in 1979 and taken nationally in 1980, JAG-K partners with schools and students to help them complete high school and then get on a career path. Whether they pursue post-secondary education, vocational training, the military or move directly into the workforce, our students are guided by JAG-K Career Specialists (Specialists) along the way. JAG-K Specialists invest time, compassion, understanding and love into the program and their students. The specialists continue to work with students for a full year past high school. The results are amazing. Our JAG-K students have a graduation rate exceeding 91 percent statewide, and more than 84 percent are successfully employed or on a path to employment. These are results for students who were generally not on a path to success prior to participating in JAG-K. We believe JAG-K could be part of the statewide solution in addressing “at-risk” students who may not be on track to graduate or need some additional assistance. Although JAG-K is an elective class during the school year, our Specialists maintain contact and offer student support throughout the summer months and during a 12 -month follow-up period after their senior year. -

KDWPT Kiosk Part 1

Wetlands and Wildlife National Scenic Byway There are over 800 bird Welcome to the Wetlands and Wildlife National The Wetlands and Wildlife National Scenic egrets, great blue herons, whooping cranes, and species in the United States Byway is one of a select group designated bald eagles. Cheyenne Bottoms and Quivira are Scenic Byway, showcasing the life of two of with over 450 found in by the Secretary of the U.S. Department home to nearly half of America’s bird species, of Transportation as “America’s Byways,” 19 reptile species, nine amphibian species, and the world’s most important natural habitats. Kansas and over 350 in offering special experiences of national and a variety of mammals. At the superb Kansas Cheyenne Bottoms and international significance. The byway connects Wetlands Education Center, along the byway two distinctly diverse types of wetlands that and adjacent to Cheyenne Bottoms, state-of-the- Quivira. Besides birds, attract a worldwide audience of birdwatchers, art exhibits and expert naturalists will introduce there are 23 species of lovers of wildlife, photographers, naturalists, the subtle wonders of the area. mammals, 19 species of and visitors in search of the quiet beauty of nature undisturbed. On the southern end of the byway, the 22,000- reptiles, and nine species of acre Quivira National Wildlife Refuge offers Cheyenne Bottoms is America’s largest inland a contrasting wetlands experience – a rare amphibians. freshwater marsh and hosts a staggering inland saltwater marsh. The refuge’s marshes, variety of wildlife. It is considered one of the sand dunes, prairies, and timber support most important stopping points for shorebird such endangered species as the least tern and migration in the Western Hemisphere, snowy plover and provide habitats for quail, hosting tens of thousands of North America’s meadowlarks, raptors, and upland mammals. -

2018 Canadian NAWMP Report

September 2018 nawmp.wetlandnetwork.ca HabitatMatters 2018 Canadian NAWMP Report “Autumn Colours – Wood Duck” from the 2018 Canadian Wildlife Habitat Conservation Stamp series. Artist: Pierre Girard North American Waterfowl Management Plan —— Plan nord-américain de gestion de la sauvagine —— Plan de Manejo de Aves Acuáticas Norteamérica TableContents of 1 About the NAWMP 2 National Overview 2 Accomplishments 3 Expenditures and Contributions 4 Canadian Waterfowl Habitat Benefits All North Americans 6 Habitat Joint Ventures 7 Prairie Habitat Joint Venture 12 Eastern Habitat Joint Venture 17 Pacific Birds Habitat Joint Venture 23 Canadian Intermountain Joint Venture 28 Species Joint Ventures 29 Sea Duck Joint Venture 31 Black Duck Joint Venture 33 Arctic Goose Joint Venture 36 Partners About the NAWMP Hooded Merganser duckling. The North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP) Laura Kaye is an international partnership to restore, conserve and protect waterfowl populations and associated habitats through management decisions based on strong biological waterfowl populations. Mexico became a signatory to the foundations. The ultimate goal is to achieve abundant and NAWMP with its update in 1994. As a result, the NAWMP resilient waterfowl populations and sustainable landscapes. partnership extends across North America, working at national The NAWMP engages the community of users and supporters and regional levels on a variety of waterfowl and habitat committed to conserving and valuing waterfowl and wetlands. management issues. In 1986, the Canadian and American governments signed this Since its creation, the NAWMP’s partners have worked to international partnership agreement, laying the foundation conserve and restore wetlands, associated uplands and other for international cooperation in the recovery of declining key habitats for waterfowl across Canada, the United States and Mexico. -

Jan Garton and the Campaign to Save Cheyenne Bottoms

POOL 2 –CHEYENNE BOTTOMS, 1984 “Now don’t you ladies worry your pretty little heads. There’s $2,000 in our Article by Seliesa Pembleton budget to take care of the Bottoms this summer.” With those words we were Photos by Ed Pembleton ushered from the office of an indifferent agent of the Kansas Fish and Game Commission (now Kansas Department of Wildlife Parks, and Tourism). Little did he know those were fighting words! snewofficersoftheNorthernFlint Jan Garton came forward to volunteer endangered, too. Water rights for the Hills Audubon Chapter in as conservation committee chair, and with Bottoms were being ignored; stretches of AManhattan, Jan Garton and I had some urging, also agreed to be chapter the Arkansas River were dry; and flows travelled to Pratt seeking a copy of a secretary. We set about finding other from Walnut Creek, the immediate water Cheyenne Bottoms restoration plan community leaders to fill the slate of source, were diminished. prepared years before by a former officers and pull the organization out of Bottoms manager. We were dismissively its lethargy. We recognized the need for a Like a Watershed: Gathering told, “It’s around here somewhere.” compelling cause to rally around and Jan Information & Seeking Advice Managing to keep her cool, Jan informed immediately identified Cheyenne Bottoms Our first actions were to seek advice the agent he needed to find it because we as the issue that inspired her to volunteer. from long-time Audubon members and would be back! On the drive home from By the end of the first year, chapter others who shared concern about the that first infuriating meeting we had time membership had almost doubled in part Bottoms. -

Des Oueds Mythiques Aux Rivières Artificielles : L'hydrographie Du Bas-Sahara Algérien

P hysio-Géo - Géographie Physique et Environnement, 2010, volume IV 107 DES OUEDS MYTHIQUES AUX RIVIÈRES ARTIFICIELLES : L'HYDROGRAPHIE DU BAS-SAHARA ALGÉRIEN Jean-Louis BALLAIS (1) (1) : CEGA-UMR "ESPACE" CNRS et Université de Provence, 29 Avenue Robert Schuman, 13621 AIX-EN- PROVENCE. Courriel : [email protected] RÉSUMÉ : À la lumière de recherches récentes, l'hydrographie du Bas-Sahara est revisitée. Il est montré que les oueds mythiques, Igharghar à partir du sud du Grand Erg Oriental, Mya au niveau de Ouargla et Rhir n'existent pas. Parmi les oueds réels fonctionnels, on commence à mieux connaître ceux qui descendent de l'Atlas saharien avec leurs barrages et beaucoup moins bien ceux de la dorsale du M'Zab. Des oueds réels fossiles viennent d'être découverts dans le Souf, à l'amont du Grand Erg Oriental. Les seules vraies rivières, pérennes, tel le grand drain, sont celles alimentées par les eaux de collature des oasis et des réseaux pluviaux des villes. MOTS CLÉS : oueds mythiques, oueds fossiles, oueds fonctionnels, rivières artificielles, Bas-Sahara, Algérie. ABSTRACT: New researches on Bas-Sahara hydrography have been performed. They show that mythical wadis such as wadi Igharghar from south of the Grand Erg Oriental, wadi Mya close to Ouargla and wadi Rhir do not exist. Among the functional real wadis, those that run from the saharan Atlas mountains are best known, due to their dams. Those of the M'Zab ridge are still poorly studied. Fossil real wadis have been just discovered in the Souf region, north of the Grand Erg Oriental. -

Habitat Model for Species

Habitat Model for Species: Yellow Mud Turtle Distribution Map Kinosternon flavescens flavescens Habitat Map Landcover Category 0 - Comments Habitat Restrictions Comments Collins, 1993 Although presence of aquatic vegetation is preferred (within aquatic habitats), it is not necessary. May forage on land and is frequently found crawling from one body of water to another, Webb, 1970 Study in OK. Described as a grassland species. Royal, 1982 Study in KS. Two individuals found on unpaved road between the floodplain and dune sands in Finney Co. Kangas, 1986 Study in Missouri. Abundance of three populations could be accounted for by amount of very course sand in their Webster, 1986 Study Kansas. Species prefers a tan-colored loess "mud" to a dark-brown sandy loam bottom. Addition of aquatic plants to sandy loam caused a shift to vegetated [#KS GAP] All habitat selections were bases on listed criteria (in comment section) and the presence of the selected habitat in the species known range in Kansas. [#Reviewer] Platt: Most observations on upland are within 20-30 feet of an aquatic habitat. But it is sometimes found much farther from water, probably migrating grom one pond to [#Reviewer2] Distler: On the Field Station, observed once in 17 years along abandoned road though cottonwood floodplain woodland, which is adjacent to CRP. 15 - Buttonbush (Swamp) Shrubland Collins, 1993 26 - Grass Playa Lake Kangas, 1986 Study in Missouri. Selected based on "marsh" in Habitat section and species range. 27 - Salt Marsh/Prairie Kangas, 1986 Study in Missouri. Selected based on "marsh" in Habitat section and species range. 28 - Spikerush Playa Lake Kangas, 1986 Study in Missouri. -

Ramsar COP8 DOC. 29 Regional Overview of the Implementation Of

“Wetlands: water, life, and culture” 8th Meeting of the Conference of the Contracting Parties to the Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971) Valencia, Spain, 18-26 November 2002 Ramsar COP8 DOC. 29 Information Paper English and Spanish only Regional overview of the implementation of the Convention and its Strategic Plan 1997-2002: North America The National Reports upon which this overview is based can be consulted on the Ramsar Web site, on http://ramsar.org/cop8_nr_natl_rpt_index.htm Contracting Parties in North America: Canada, Mexico, and United States of America (3). Contracting Parties whose National Reports are included in this analysis: Canada, Mexico, United States of America (3). 1. Main achievements since COP7 and priorities for 2003-2005 1.1 Main achievements since COP7 1. There are 3 countries in the North America region; all are already Contracting Parties. 2. To 31 August 2002 the region has 61 Ramsar sites, covering an area of almost 15.4 million hectares. This represents approximately 15% of the world’s Wetlands of International Importance. 3. In COP7 Resolution VII.12, Canada committed itself to designating three new sites and carrying out two site expansions. Since COP7 only two new Ramsar sites were designated in North America: Dzilam (reserva estatal) in Mexico, and Quivira National Wildlife Refuge in the United States of America (USA), covering 61,707 and 8,958 ha. respectively. Additionally, two sites were expanded in the same period: Cheyenne Bottoms State Game Area in the USA – extension of 2,942 ha; total site area of 10,978 ha – and Mer Bleue Conservation Area in Canada – extension of 243 ha; total site area of 3,343 ha. -

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus Adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2020 Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes Emily Rebecca Mausteller [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Mausteller, Emily Rebecca, "Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes" (2020). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1313. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1313 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EASTERN DIAMONDBACK RATTLESNAKE (CROTALUS ADAMANTEUS) AMBUSH SITE SELECTION IN COASTAL SALTWATER MARSHES A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Biological Sciences by Emily Rebecca Mausteller Approved by Dr. Shane Welch, Committee Chairperson Dr. Jayme Waldron Dr. Anne Axel Marshall University December 2020 i APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Emily Mausteller, affirm that the thesis, Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) Ambush Site Selection in Coastal Saltwater Marshes, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the Biological Sciences Program and the College of Science. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. -

Cheyenne Bottoms, Barton County

Cheyenne Bottoms, Barton County. 2KANSAS HISTORY CREATING A “SEA OF GALILEE” The Rescue of Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area, 1927–1930 by Douglas S. Harvey ot long ago, Cheyenne Bottoms, located in Barton County, Kansas, was the only lake of any size in the state of Kansas. After a big rainstorm, it was the largest body of water within hundreds of miles. But when the rains failed to come, which was more often than not, the Bottoms would be invisible to the untrained eye— just another trough in a sea of grass. Before settlement, when the Indian and bison still dominated the region, Nephemeral wetlands and springs such as these meant the difference between life and death for many inhabitants of the Central Plains. Eastward-flowing streams briefly interrupted the sea of grass and also provided wood, water, and shelter to the multitude of inhabitants, both two- and four-legged. Flocks of migratory birds filled the air in spring and fall, most migrating between nesting grounds in southern Canada and the arctic and wintering grounds near the Gulf of Mexico and the tropics. These migrants rejuvenated themselves on their long treks at these rivers, but especially they relied on the ephemeral wetlands that dotted the Plains when the rains came.1 Douglas S. Harvey is an assistant instructor of history and Ph.D. student at the University of Kansas. He received his master’s degree in history from Wichita State University. Research interests include wetlands of the Great Plains, ecological remnants of the Great Plains, and bison restoration projects. The author would like to thank Marvin Schwilling of Emporia, the Barton County Title Company, Helen Hands and Karl Grover at Cheyenne Bot- toms, and everyone else who assisted in researching this article. -

The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands

NATIONAL WETLANDS NEWSLETTER, vol. 29, no. 2. Copyright © 2007 Environmental Law Institute.® Washington D.C., USA.Reprinted by permission of the National Wetlands Newsletter. To subscribe, call 800-433-5120, write [email protected], or visit http://www.eli.org/nww. The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands: Assessment of International Designations Within the United States The Ramsar Convention is an international framework used to protect wetlands. At this time, the United States has 22 designated sites listed as wetlands of international importance. In this Article, the authors analyze survey data collected from each of these 22 sites to determine whether and how Ramsar designation benefits these wetland areas. BY ROYAL C. GARDNER AND KIM DIANA CONNOLLY ssues related to wetlands and wetland protection often involve engage in international cooperation.6 Its nonregulatory approach boundaries. Sometimes the lines are drawn on the ground, has led some to ask what benefits are associated with Ramsar des- delineating between so-called “jurisdictional” wetlands and ignation. For example, the United States has a maze of federal, uplands. Sometimes the boundaries are conceptual: trying state, and local laws that protect wetlands, so does the international Ito determine the proper relationship between the federal and state recognition of a site provide any additional returns? To answer governments with respect to wetland permits, or trying to balance this question, we surveyed all 22 U.S. Ramsar sites.7 Although the the need to protect the aquatic environment without inappropri- results varied from site to site, we found that Ramsar designation ately limiting activities on private property. Other times interna- adds some value to all sites. -

Accomplishment Plan

Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council Laws of Minnesota 2019 Accomplishment Plan General Information Date: 05/10/2021 Project Title: Shallow Lake & Wetland Protection & Restoration Program - Phase VIII Funds Recommended: $6,150,000 Legislative Citation: ML 2019, 1st Sp. Session, Ch. 2, Art. 1, Sec. 2, subd, 4(b) Appropriation Language: $6,150,000 the first year is to the commissioner of natural resources for an agreement with Ducks Unlimited to acquire lands in fee and to restore and enhance prairie lands, wetlands, and land buffering shallow lakes for wildlife management under Minnesota Statutes, section 86A.05, subdivision 8. A list of proposed acquisitions must be provided as part of the required accomplishment plan. Manager Information Manager's Name: Jon Schneider Title: Manager Minnesota Conservation Program Organization: Ducks Unlimited Address: 311 East Lake Geneva Road City: Alexandria, MN 56308 Email: [email protected] Office Number: 3207629916 Mobile Number: 3208150327 Fax Number: 3207591567 Website: www.ducks.org Location Information County Location(s): Kandiyohi, Lincoln, Murray, Jackson, Lyon, Redwood, Cottonwood, Swift, Sibley, Big Stone and Meeker. Eco regions in which work will take place: Prairie Activity types: Protect in Fee Priority resources addressed by activity: P a g e 1 | 15 Wetlands Prairie Narrative Abstract This Phase 8 request funds Ducks Unlimited’s prairie land acquisition and restoration program. DU will acquire 560 acres of land containing drained wetlands in the Prairie Pothole Region of SW Minnesota for restoration and transfer to the Minnesota DNR for inclusion in the state WMA system. This land acquisition and restoration program focuses on restoring cropland with wetlands along shallow lakes and adjoining WMAs containing large wetlands to help restore prairie wetland habitat complexes for breeding ducks and other wildlife.