Performance and the Making of Holy Persons in Society and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(POST)COLONIAL AFRICA by Katherine Lynn Coverdale the F

ABSTRACT AN EXPLORATION OF IDENTITY IN CLAIRE DENIS’ AND MATI DIOP’S (POST)COLONIAL AFRICA by Katherine Lynn Coverdale The focus of this thesis is aimed at two female French directors: Claire Denis and Mati Diop. Both auteurs utilize framing to create and subsequently break down ideological boundaries of class and race. Denis’ films Chocolat and White Material show the impossibility of a distinct identity in a racialized post-colonial society for someone who is Other. With the help of Laura Mulvey and Richard Dyer, the first chapter of this work on Claire Denis offers a case study of the relationship between the camera and race seen through a deep analysis of several sequences of those two films. Both films provide an opportunity to analyze how the protagonists’ bodies are perceived on screen as a representation of a racial bias held in reality, as seen in the juxtaposition of light and dark skin tones. The second chapter analyzes themes of migration and the symbolism of the ocean in Diop’s film Atlantique. I argue that these motifs serve to demonstrate how to break out of the identity assigned by society in this more modern post-colonial temporality. All three films are an example of the lasting violence due to colonization and its seemingly inescapable ramifications, specifically as associated with identity. AN EXPLORATION OF IDENTITY IN CLAIRE DENIS’ AND MATI DIOP’S (POST)COLONIAL AFRICA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Katherine Lynn Coverdale Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2020 Advisor: Dr. -

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Votes and Proceedings

SECOND SESSION THIRTY-NINTH LEGISLATURE Votes and Proceedings of the Assembly Thursday, 19 May 2011 — No. 29 President of the National Assembly: Mr. Jacques Chagnon QUÉBEC Thursday, 19 May 2011 No. 29 The Assembly was called to order at 9.46 o'clock a.m. _____________ ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS Statements by Members Mrs. Houda-Pepin (La Pinière) made a statement to pay homage to the Moroccan women of the Americas. _____________ Mr. St-Arnaud (Chambly) made a statement to pay homage to Paul Bertrand dit St-Arnaud. _____________ Mrs. Vien (Bellechasse) made a statement about Hearing Month. _____________ Mrs. Champagne (Champlain) made a statement about the Association des descendants de Paul Bertrand dit St-Arnaud. _____________ 321 19 May 2011 Mr. Bonnardel (Shefford) made a statement to congratulate Mrs. Isabelle Lisé and Mr. Joslin Coderre on their efforts to make their golf club a greener place. _____________ Mr. Khadir (Mercier) made a statement to commemorate the Nakba and the victory of democracy in Palestine. _____________ Mr. Pelletier (Rimouski) made a statement about the award won by the UQAR at the Chambre de commerce du Québec gala. _____________ Mr. Hamad (Louis-Hébert) made a statement to underline the presence in the galleries of students from a dozen Québec City elementary schools. _____________ Mr. Simard (Kamouraska-Témiscouata) made a statement to pay homage to Mr. Adrien Gagnon. _____________ At 9.57 o'clock a.m., Mr. Ouimet, Second Vice-President, suspended the proceedings for a few minutes. _____________ 322 19 May 2011 The proceedings resumed at 10.12 o'clock a.m. _____________ Moment of reflection Introduction of Bills Mr. -

Saint Matthew Church the PULSE

Saint Matthew Church The PULSE October 14, 2018 Detroit, Michigan MASS OF ANOINTING ~ THIS WEEKEND Saturday, 4:30 pm ~ Sunday, 10:00 am Readings for the Week of October 14, 2018 Saints Isaac Jogues, Jean de Brébeuf, and Companions’ Story ~ Feast Day, October 19 Sunday: Wis 7:7-11/Ps 90:12-13, 14-15, 16-17 [14]/ Heb 4:12-13/Mk 10:17-30 or 10:17-27 Isaac Jogues and his companions were the first martyrs of Monday: Gal 4:22-24, 26-27, 31--5:1/Ps 113:1b-2, 3-4, the North American continent officially recognized by the 5a and 6-7 [cf. 2]/Lk 11:29-32 Church. As a young Jesuit, Isaac Jogues, a man of learning Tuesday: Gal 5:1-6/Ps 119:41, 43, 44, 45, 47, 48 [41a]/ and culture, taught literature in France. He gave up that career Lk 11:37-41 to work among the Huron Indians in the New World, and in Wednesday: Gal 5:18-25/Ps 1:1-2, 3, 4 and 6 [cf. Jn 8:12]/ 1636, he and his companions, under the leadership of Jean de Lk 11:42-46 Brébeuf, arrived in Quebec. The Hurons were constantly Thursday: 2 Tm 4:10-17b/Ps 145:10-11, 12-13, 17-18 warred upon by the Iroquois, and in a few years Father Jogues was captured by the Iroquois and imprisoned for 13 months. [12]/Lk 10:1-9 His letters and journals tell how he and his companions were Friday: Eph 1:11-14/Ps 33:1-2, 4-5, 12-13 [12]/ led from village to village, how they were beaten, tortured, and Lk 12:1-7 forced to watch as their Huron converts were killed. -

WWII Veterans Last Name L

<%@LANGUAGE="JAVASCRIPT" CODEPAGE="65001"%> WWII Veterans last name L Labbe, Lawrence A. 9 Lea St. Label, Raoul 33 Hampton St. Labell, Morris 10 Concord St. LaBelle, Leo Desire 78 Exchange St. LaBelle, Paul A. 27 Farley St. Laberge, Fernand A. 444 Haverhill St. LaBonte, Andrew Shea 1085 Essex St. Labonte, Jean P. 439 South Broadway Labonte, John P. 439 South Broadway Labonte, Louis J. 5 Atkinson St. Labonte, Paul 439 South Broadway Labranche, Alfred 507 Essex St. Labranche, Armand C. 16 Bennett St. LaBranche, Claude G. 12 Tremont St. Labrecque, George A. Labrecque, Gerard J. Labrecque, John W. 13 Wyman St. Labrecque, Rene A. 108 Margin St. Labrie, Lionel 6 Cedar St. Lacaillade, Francis M. Lacaillade, Maurice C. LaCarte, John L. 28 Congress St. LaCarubba, John S. 34 Wilmot St. LaCarubba, Mario J. 34 Wilmot St. Lacasse, Albert J. 329 Broadway Lacasse, Andrew L. Lacasse, Arthur P. 329 Broadway Lacasse, Edward R. 329 Broadway Lacasse, Hubert L. 88 Columbus Ave. Lacasse, Joseph Lacasse, Wilfred V. 152 Spruce St. Lacey, Alphonse M. Lacey, Julian J. 57 Juniper St. Lacey, Richard L. 49 Avon St. LaChance, Albert Elizard 35 Tremont St. LaChance, Arthur R. 35 Irene St. LaChance, Julian 57 Groton St. LaChance, Ronald J. Lachance, Victor T. LaChapelle, Wilbrod A. 154 Margin St. Lacharite, Edward A. 34 Bellevue St. Lacharite, Edward A. 34 Bellevue St. 1 of 14 LaCharite, Leonard LaCharite, Robert F. 99 Arlington St. Lacharite, Wilfred E. Lacolla, Vincent 35 Sargent St. Lacourse, George J. Lacouter, Francis Roy Lacroix, Adelard Lacroix, Ernest Wilfred LaCroix, Henry E. Oxford St. Lacroix, Lionel 327 South Broadway LaCroix, Louis Lacroix, Maurice J. -

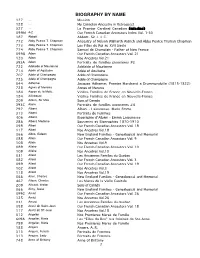

Biography by Name 127

BIOGRAPHY BY NAME 127 ... Missing 128 ... My Canadian Ancestry in Retrospect 327 ... Le Premier Cardinal Canadien (missing) 099M A-Z Our French Canadian Ancestors Index Vol. 1-30 187 Abbott Abbott, Sir J. J. C. 772 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Ancestry of Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich and Abby Pearce Truman Chapman 773 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Les Filles du Roi au XVII Siecle 774 Abby Pearce T. Chapman Samuel de Champlain - Father of New France 099B Adam Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 21 120 Adam Nos Ancetres Vol.21 393A Adam Portraits de familles pionnieres #2 722 Adelaide of Maurienne Adelaide of Maurienne 714 Adele of Aquitaine Adele of Aquitaine 707 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 725 Adele of Champagne Adele of Champagne 044 Adhemar Jacques Adhemar, Premier Marchand a Drummondville (1815-1822) 728 Agnes of Merania Agnes of Merania 184 Aigron de la Motte Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 184 Ailleboust Vieilles Familles de France en Nouvelle-France 209 Aitken, Sir Max Sons of Canada 393C Alarie Portraits de familles pionnieres #4 292 Albani Albani - Lajeunesse, Marie Emma 313 Albani Portraits de Femmes 406 Albani Biographie d'Albani - Emma Lajeunesse 286 Albani, Madame Souvenirs et Biographies 1870-1910 098 Albert Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 18 117 Albert Nos Ancetres Vol.18 066 Albro, Gideon New England Families - Genealogical and Memorial 088 Allain Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 9 108 Allain Nos Ancetres Vol.9 089 Allaire Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. 10 109 Allaire Nos Ancetres Vol.10 031 Allard Les Anciennes Familles du Quebec 082 Allard Our French Canadian Ancestors Vol. -

Blackbourn Veronica a 20101

The Beloved and Other Monsters: Biopolitics and the Rhetoric of Reconciliation in Post-1994 South African Literature by Veronica A. Blackbourn A thesis submitted to the Department of English Language and Literature In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (December, 2010) Copyright © Veronica A. Blackbourn, 2010 Abstract This dissertation examines the use of inter-racial relationships as emblems of political reconciliation in South African fiction from and about the transition from apartheid to democracy. Positive representations of the relationships that apartheid prohibited would seem to constitute a rejection of apartheid itself, but through an analysis of novels by Lewis DeSoto, Elleke Boehmer, Zoë Wicomb, Marlene van Niekerk, Ivan Vladislavić, and J.M. Coetzee, I argue that the trope of the redemptive inter-racial relationship in fact reinscribes what Foucault would designate a biopolitical obsession with race as a foundational construct of the nation. Chapter 2 examines an attempt to write against the legacy of apartheid by repurposing the quintessentially South African genre of the plaasroman, but Lewis DeSoto‘s A Blade of Grass (2003) fails to reverse the narrative effects created by the plaasroman structure, implicated as the plaasroman is and has been in a biopolitical framework. Chapter 3 examines Elleke Boehmer‘s rewriting of South African history to insist on the genealogical ―truth‖ of the racial mixing of the country and its inhabitants, but Bloodlines (2000) yet retains the obsession with racial constructs that it seeks to dispute. Zoë Wicomb‘s Playing in the Light (2006), meanwhile, invokes genealogical ―truth‖ as a corrective to apartheid constructions of race, but ultimately disallows the possibility of genealogical and historical narratives as correctives rather than continuations of apartheid. -

1642 and 1649 by Iroquois Natives

Canadian Martyrs Church officially blessed Half a country away, Midland, Ont., there is a shrine dedicated to eight Canadian Jesuit Martyrs killed between 1642 and 1649 by Iroquois natives. Now a new church at 5771 Granville Ave. in Richmond has been dedicated to the memory of Sts. Isaac Jogues, Jean de Brebeuf, Charles Garnier, Anthony Daniel, Gabriel Lalemant, Noel Chabanel, John La Lande and Rene Goupil, Jesuit pioneering missionaries who brought the Gospel to the Huron and Iroquois in Canada and the U.S. All were priests except the Jesuit associates Rene Goupil, who was a surgeon, and John La Lande. They were beautified by Pope Pius XI on June 21, 1925, and canonized by the same Pontiff five years later. On March 2, nearly 1,000 jubilant parishioners crowded into the new church while an overflow audience watched the dedication Mass via a closed-circuit broadcast in the parish hall. Archbishop Adam Exner, OMI, exhorted Canadian Martyrs’parishioners to adhere to their sainted patrons’ legacy of “determination, steadfast faith, and unwavering commitment to building up the Kingdom of God here on earth.” The house, he said, is a witness of their faith to all who look upon it. “The parishioners of this parish, most of them, have come from faraway countries and have seen the need to build a new parish. After much searching, the land and the church were bought. Many of you were here for the blessing of the first church. Soon after, it became clear that the church was simply too small and that a new and larger church and parish facilities were needed. -

CUHSLMCM M165.Pdf (932.2Kb)

Volume 25, Annual Meeting Issue October, 2004 2004 MCMLA Award Winners MCMLA 2004 Wrap-Up Sarah Kirby, Chair Lenora Kinzie 2004 MCMLA Awards Committee 2003-04 MCMLA Chair On behalf of the MCMLA 2004 Honors & Awards Thanks to all who worked so hard to make 2004 a Committee, I would like to announce the winners. great year! Lots of exciting changes have taken place All of the candidates are winners! It was a difficult and there is more to come. The idea for a special decision because all of the candidates are very annual meeting MCMLA EXPRESS is an excellent outstanding and very qualified. example of changes taking place. The new web redesign is another. Have you been online yet to Barbara McDowell Award Erica Lake check it out? Special thanks to the Publications Committee. Bernice M. Hetzner Award Lisa Traditi Outsta nding Achievement Award Peggy Mullaly-Quijas The following recap of my Kansas City Chair Report is a short review of the past year…actions, decisions, and future plans. The Business Meeting minutes with Erica Lake is the medical librarian at LDS additional details will be on the web page in the very Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. Erica has made a near future. major impact as a leader in her hospital system, Intermountain Health Care. She has been a Leadership Grant: Last November we applied for dynamic force in the evaluation and selection of MLA’s Leadership and Management Section grant to electronic databases with corporate-wide access. provide additional funding to support Dr. Michelynn Erica is very active in the local consortium, Utah McKnight’s CE presentation “Proving Your Worth” Health Sciences Library Consortium, and is at the annual meeting. -

Sacred Heart Parish

Liturgical Publications 3171 LENWORTH DR. #12 MISSISSAUGA, ON L4X 2G6 1-800-268-2637 Sacred Heart Parish Pastor: 17 Washington Street, SPOT Father Jeff Bergsma Paris, Ontario N3L 2A2 You can book an appointment 519-442-2465 Fax: 519- 442-1475 with Father at [email protected] Shopping Locally Saves Gas! www.sacredheartparishparis.com SPOT fatherbergsma.youcanbook.me Welcome to Sacred Heart Parish For advertising space please call 1-800-268-2637 250 - 1 SPOT Remember... DO YOU HAVE A Let our advertisers know PRODUCT OR you saw their ad here. Sunday Mass Times: Confessions: Saturday 5pm Saturday 11am-12pm SERVICE TO This bulletin is Sunday 9am and 11am or by appointment SPOT OFFER? provided ADVERTISE IT IN YOUR LOCAL CHURCH BULLETIN each week to your Weekday Mass Times: Matrimony: EFFECTIVE TRUSTED AND REASONABLY PRICED 1-800-268-2637 Tuesday - Friday 9am Speak with Father one year in church at no charge. advance. The advertisers Baptism: make this possible! Second Sunday of the month. Parish Groups: Please patronize Registration forms available Catholic Women's League online and at the back of the St. Vincent DePaul them and let them Church. Be A Man (Brantford Area) know where you saw their ad! Parish Schools: New Parishioners: Sacred Heart of Jesus We welcome you to our parish 519-442-4443 family. Please fill out a parish Holy Family registration form, they are available 519-442-5333 at the back of the Church. 250 - 1 THIRTY-FIRST SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME NOVEMBER 5, 2017 250 - 1 Next Week’s Mass Schedule: St. Marguerite d'Youville (1701–1771). -

POPE JOHN PAUL II ASSEMBLY NEWS Volume 5, Issue 8 March 2014 Affiliated Councils: Monsignor James Corbett Warren Memorial Council 5073 St

POPE JOHN PAUL II ASSEMBLY NEWS Volume 5, Issue 8 March 2014 Affiliated Councils: Monsignor James Corbett Warren Memorial Council 5073 St. Gabriel Council 10061 Conseil St. Antoine-Daniel 10340 Faithful Friar's Message: “This is the time of fulfilment. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the “Good News”. (Mark 1:15) Next Wednesday is Ash Wednesday. It is a time when we switch gears to look at our journey of faith. We recall our baptismal promises and how we are fulfilling our call as disciples of the Lord. It is a time to strengthen our faith, prayer life and sacrifice during this penitential time. It is also the time when we welcome the catechumens make their final preparation to enter into the Catholic Faith. Many of us have been sponsors to some of them. How do we show the example of Faith, Hope and Love to them and to our families and at council meetings. Prayer, fasting and almsgiving should be our companions in the journey of Lent. As fellow Knights, we should try to be more faithful to our meetings and our service. Do not always leave it to the faithful few. We have many members in our councils. During this Lenten time, I encourage all the members to think and commit more time to our councils and parishes without neglecting our families. It is imperative that each of us give the example of prayer, fasting and reaching out to those in need. Pax Tecum “Who fasts, but does no other good, saves his bread, Fr. -

Midland Exploration Options to Probe Metals Its La Peltrie Gold Property East of Lower Detour Zone 58N

MIDLAND EXPLORATION OPTIONS TO PROBE METALS ITS LA PELTRIE GOLD PROPERTY EAST OF LOWER DETOUR ZONE 58N Montreal, July 9, 2020. Midland Exploration Inc. (“Midland”) (TSX-V: MD) is pleased to announce the execution of an option agreement with Probe Metals Inc. (“Probe”) for its La Peltrie gold property. The La Peltrie property, wholly owned by Midland, consists of 435 claims (240 square kilometres) and covers, over a distance of more than 25 kilometres, a series of NW-SE-trending subsidiary faults to the south of the regional Lower Detour Fault. The La Peltrie property is located approximately 25 kilometres southeast of the high-grade Lower Detour Zone 58N deposit held by Kirkland Lake Gold Ltd, which hosts indicated resources totalling 2.87 million tonnes at a grade of 5.8 g/t Au (534 300 oz Au) and inferred resources totalling 0.97 million tonnes at a grade of 4.35 g/t Au (136 100 oz Au). It is also located proximal to the B26 deposit held by SOQUEM, where indicated resources are estimated at 6.97 million tonnes grading 1.32% Cu, 1.80% Zn, 0.60 g/t Au and 43.0 g/t Ag, and inferred resources at 4.41 million tonnes grading 2.03% Cu, 0.22% Zn, 1.07 g/t Au and 9.0 g/t Ag (see press release by SOQUEM dated March 4, 2018). The La Peltrie property is also located 25 kilometres northwest of the former Selbaie mine, which historically produced 56.5 million tonnes of ore grading 1.9% Zn, 0.9% Cu, 38.0 g/t Ag and 0.6 g/t Au.