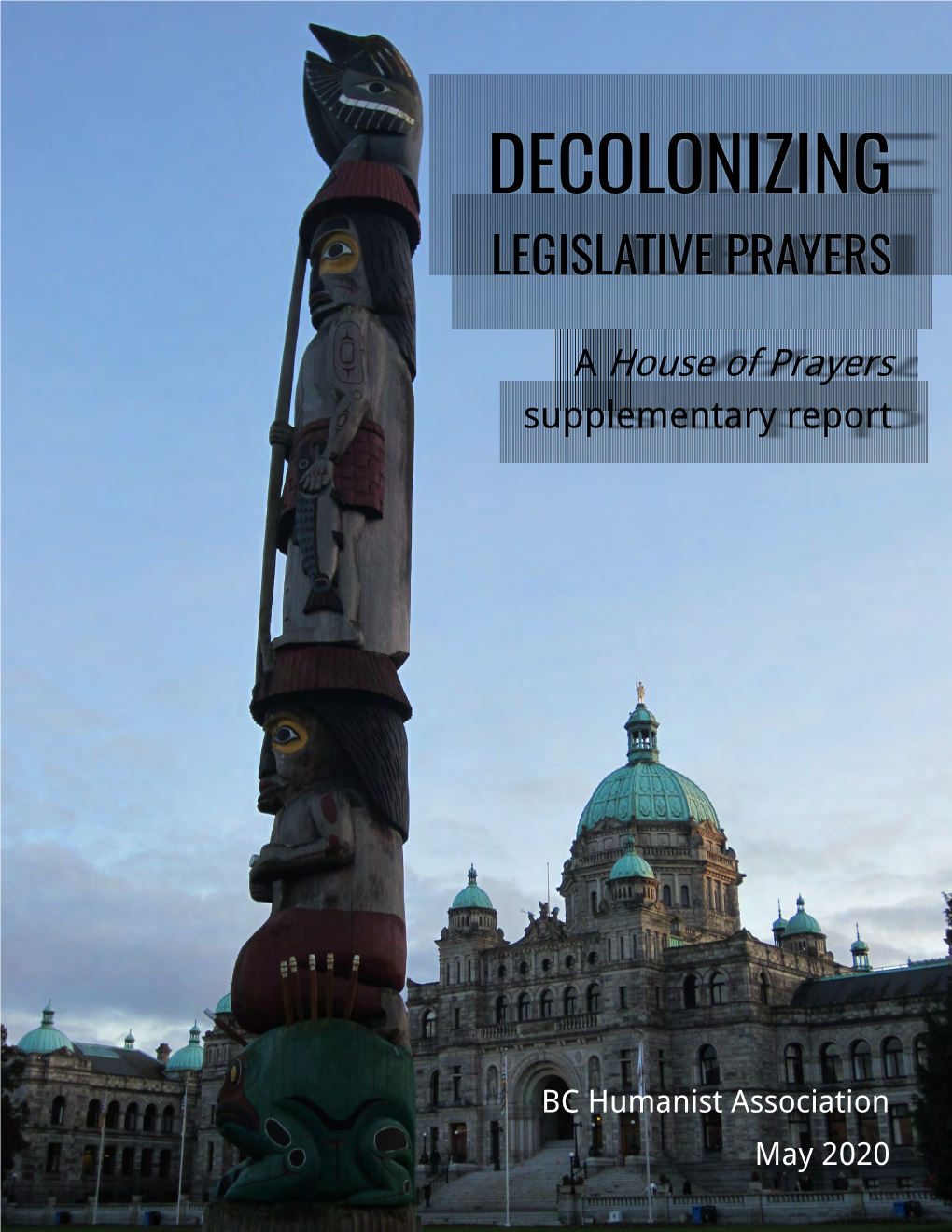

Decolonizing Legislative Prayers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report June 2, 2020 Today in BC

BC Today – Daily Report June 2, 2020 Quotation of the day “I cannot control people's activities — what I can do is provide you with the necessary advice and tools that you need to have a peaceful demonstration in a way that is not going to imperil your family, your loved ones, your community during this time and this pandemic.” Dr. Bonnie Henry cautions that public demonstrations — like the anti-racism demonstration that took place at the Vancouver Art Gallery yesterday — may be risky for community health. Today in B.C. On the schedule The house will reconvene for a summer session on June 22. Dr. Bonnie Henry and Health Minister Adrian Dix will provide an update on COVID-19 in B.C. at 3 p.m. Landlords who don't apply for aid can't evict businesses A new order under B.C.’s Emergency Program Act will protect eligible businesses from eviction if their landlords do not apply for the Canada Emergency Commercial Rent Assistance (CECRA) program. The federal program officially opened last week and uptake hasn’t met expectations, according to Finance Minister Carole James. “We’ve heard from small businesses and MLAs around the province that there are certainly some tenants [whose] landlords have been very clear that they don't want to bother, they don't want to take the time to apply for the federal program,” James told reporters. James hopes the order — which restricts commercial landlords from evicting tenants due to non-payment of rent, repayment lawsuits and repossession of property and goods — will encourage commercial landlords to apply to the federal aid program. -

…/2 March 30, 2020 Honourable John Horgan Honourable Carole James

March 30, 2020 Honourable John Horgan Honourable Carole James Honourable Lisa Beare Honourable Michelle Mungall Premier of British Columbia Minister of Finance and Minister of Tourism, Minister of Jobs, Economic West Annex Deputy Premier Arts and Culture Development and Competitiveness Parliament Buildings Room 143 Room 151 Room 301 Victoria, BC V8V 1X4 Parliament Buildings Parliament Buildings Parliament Buildings Victoria, BC V8V 1X4 Victoria, BC V8V 1X4 Victoria, BC V8V 1X4 Dear Premier Horgan, Minister James, Minister Beare, and Minister Mungall, April 1st is just around the corner. May 1st is coming soon after that. We don’t know how long this pandemic will last. But we know that many of our small and medium sized businesses need help to pay their rent on April 1st and will likely need the same assistance in the coming few months. Many businesses were directed to close to slow the spread of COVID-19 and to reduce the burden on our healthcare system. Many others have done so voluntarily. We acknowledge their sacrifice. As a group of community and business leaders who have been meeting twice weekly since the pandemic began to impact Victoria, we are asking you to immediately put in place rent relief measures to keep our local businesses afloat. They are the heart of our community. We’ve been hearing about the need for rent relief from businesses for a couple of weeks now. And we’re listening closely and watching for provincial measures designed to help them. The tax deferral measures you announced certainly help. The $40,000 interest free federal loan available to business for one year will also help and could be used to pay rent. -

2018 12 10 FINAL RHTF Rep

1 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Housing is the foundation of healthy families and strong communities. Having a safe place to call home is a basic and critical need for every person and every family. Unfortunately, many people in British Columbia are struggling to find a safe and secure home they can afford. Longstanding issues with the laws and regulations that govern rental housing in B.C. have made the search for, and the provision of, secure, quality, affordable housing even more difficult. Weak protections, inconsistent enforcement, and other loopholes are leaving people vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. The residential tenancy laws, policies and services are not meeting the needs of renters and rental housing providers in British Columbia today as the Residential Tenancy Act has not undergone a comprehensive review in 16 years. The existing residential tenancy system can be difficult to navigate, is outdated and fails to serve those who need it. For instance, the fact that the Act does not allow landlords and tenants to serve each other documents over email is a small example of antiquated regulations that make solving disputes more time consuming, expensive and difficult. For these reasons, Premier John Horgan appointed a Rental Housing Task Force in April 2018, to advise on how to improve security and fairness for renters and landlords throughout the province. The Task Force is composed of three members. It is led by the Premier’s Advisor on Residential Tenancy, MLA Spencer Chandra Herbert. MLA Adam Olsen, and MLA Ronna-Rae Leonard complete the team. During the spring and summer of 2018, the Rental Housing Task Force conducted a provincewide engagement with landlords, renters and others concerned citizens. -

BC Today – Daily Report February 20, 2020 Today In

BC Today – Daily Report February 20, 2020 Quotation of the day “It's not been quite three years that we've been in government … [and] it's a lot to fix after 16 years.” Finance Minister Carole James says the NDP government is struggling to fix and fund issues and programs ignored by the former Liberal rulers. Today in B.C. On the schedule The house will convene at 10 a.m. for question period. Wednesday’s debates and proceedings Attorney General David Eby introduced Bill 7, Arbitration Amendment Act, which will repeal and replace B.C.'s existing domestic arbitration framework and shift family arbitration provisions under the Family Law Act. The house spent the afternoon debating Bill 4, Budget Measures Implementation Act, which was introduced by Finance Minister Carole James on Tuesday afternoon after her budget speech. At the legislature The BC Care Providers Association hosted MLAs from both sides of the aisle at a lunch-time lobbying event. Provincial, federal officials strive for resolution to ongoing infrastructure blockades Premier John Horgan missed question period yesterday to participate in a conference call with his fellow premiers to discuss how to handle ongoing infrastructure blockades taking place across Canada in support of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who oppose the Coastal GasLink pipeline. Following the call, Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe — who currently chairs the Council of the Federation — said the premiers are calling on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to join them in a teleconference meeting today to “discuss paths to a peaceful resolution and an end to the illegal blockades.” Horgan’s office released a joint letter from B.C. -

Official Report of Debates (Hansard)

Fifh Session, 41st Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday, February 18, 2020 Morning Sitting Issue No. 307 THE HONOURABLE DARRYL PLECAS, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC Fifth Session, 41st Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Darryl Plecas EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Deputy Premier and Minister of Finance............................................................................................................................Hon. Carole James Minister of Advanced Education, Skills and Training..................................................................................................... Hon. Melanie Mark Minister of Agriculture.........................................................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General.................................................................................................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ............................................................................................................ Hon. Katrine Conroy Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. -

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY of BRITISH COLUMBIA

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY of BRITISH COLUMBIA John organ Premier of British Columbia Parliament Buildings V8V 1 X4 Dear Premier Morgan, We are writing you concerning today's introduction of the Electoral Referendum Act, 2018, a piece of legislation that will enable a province wide referendum that will ask British Columbians whether BC should adopt a voting system based on a form of proportional representation. As part of this announcement, it was outlined that the Attorney General will be acting as an independent official and that his office will be responsible for drafting the referendum process and question. It was further outlined that in order to ensure independence, the Attorney General will be recusing himself from Cabinet and/or caucus discussions regarding the referendum. We want to express our support for these measures that will ensure a fair, transparent, and legitimate referendum process and question can be developed. This question of independence also touches on the agreement outlined in the Confidence and Supply Agreement signed between our two caucuses, which creates a relationship that includes consultation on key policy measures. To further ensure that the Attorney General s office can operate with independence, we want to confirm in writing that the BC Green Caucus will not seek to consult with the Attorney General s office when it comes to evaluating submissions that are made to the ministry during the engagement phase, or on the subsequent decisions regarding the development of a referendum process and referendum question. We look forward to working with you and your caucus on directly engaging with British Columbians about the importance of changing to a system of proportional representation, and strongly campaigning in support of this once the process has been developed by the Attorney General. -

December 12, 2018

B.C. Today – Daily Report December 12, 2018 Quotation of the day “As soon as you announce your political party, a minimum of 50 per cent of your audience hates you.” NDP MLA Bowinn Ma weighs in on political partisanship in the second installment of BC Today’s deep dive into whether PR systems can change the game for female politicians. Today in B.C. On the schedule The House is adjourned for the winter break. MLAs are scheduled to return to the House on February 12, 2019 for the delivery of the government’s throne speech. B.C. Liberals continue to press for answers from the Speaker ahead of today’s committee meeting Ahead of this morning’s meeting of the Finance and Audit Committee, Liberal Party House Leader Mary Polak released an open letter listing more than a dozen “issues [that] must be addressed urgently” at the meeting, as well as the Legislative Assembly Management Committee’s (LAMC) meeting on December 19. “The credibility of the Legislature and its budget setting must be resolved prior to the expenditure of more public money on services that you have alleged to be subject to criminal activity of a financial nature,” Polak wrote in the five-page letter, which is addressed to Speaker Darryl Plecas. Many of the items — which Polak argues should be settled at the outset of the committee meetings — relate to statements made by the Speaker during last week’s LAMC meeting. Polak wants details, including the scope and timeline of forensic audits into the offices of the Speaker, clerk and sergeant-at-arms that Plecas forcefully called for. -

June 4, 2015 Letter from Premier Christy Clark to the Mayor Regarding Housing Affordability, Foreign Investment and Ownership

~YOF · CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information a Privacy File No. : 04-1 000-20-2017-468 March 14, 2018 ?.22(1) Re: Request for Access to Records under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the "Act") I I am responding to your request originally received on November 22, 2017 and then clarified · on December ·7, 2017 for: 1. Any and all subsequent written exchanges between the City .of Vancouver and the Province relating to foreign investment in local real estate from June 1, 2015 to November 21, 2017; City of Vancouver: • the Mayor's Office and Mayor Robertson Province: • The Former Premier Clark • The Current Premier Horgan • Shayne Ramsay of BC Housing • Mike de ~ong , former Minister of Finance • Carole James, current Minister of Finance • Rich Coleman, former Minister of Housing • Ellis Ross, former Minister of Housing • Selina Robinson, current Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing 2. Any and all minutes of meetings, briefing notes or other documents relating to discussions or consultations between the City of Vancouver and the Province regarding housing affordability sihce from June 1, 2015 to November 21 , 2017; and City of Vancouver: • the Mayor's Office and Mayor Robertson Province: • The Former Premier Clark City Hall 453 West 12th Avenue Vancouver BC VSY 1V4 vancouver.ca City Cle rk's Department tel: 604.873.7276 fax: 604.873.7419 • The Current Premier Horgan • Shayne Ramsay of BC Housing • Mike de Jong, former Minister of Finance • Carole James, current Minister of Finance • Rich Coleman, former Minister of Housing • Ellis Ross, former Minister of Housing • Selina Robinson, current Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing 3. -

LIST of YOUR MLAS in the PROVINCE of BRITISH COLUMBIA As of April 2021

LIST OF YOUR MLAS IN THE PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA As of April 2021 NAME RIDING CAUCUS Bruce Banman Abbotsford South BC Liberal Party Michael de Jong, Q.C. Abbotsford West BC Liberal Party Pam Alexis Abbotsford-Mission BC NDP Roly Russell Boundary-Similkameen BC NDP Janet Routledge Burnaby North BC NDP Hon. Anne Kang Burnaby-Deer Lake BC NDP Hon. Raj Chouhan Burnaby-Edmonds BC NDP Hon. Katrina Chen Burnaby-Lougheed BC NDP Coralee Oakes Cariboo North BC Liberal Party Lorne Doerkson Cariboo-Chilcotin BC Liberal Party Dan Coulter Chilliwack BC NDP Kelli Paddon Chilliwack-Kent BC NDP Doug Clovechok Columbia River-Revelstoke BC Liberal Party Fin Donnelly Coquitlam-Burke Mountain BC NDP Hon. Selina Robinson Coquitlam-Maillardville BC NDP Ronna-Rae Leonard Courtenay-Comox BC NDP Sonia Furstenau Cowichan Valley BC Green Party Hon. Ravi Kahlon Delta North BC NDP Ian Paton Delta South BC Liberal Party G:\Hotlines\2021\2021-04-14_LIST OF YOUR MLAS IN THE PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA.docx Hon. Mitzi Dean Esquimalt-Metchosin BC NDP Jackie Tegart Fraser-Nicola BC Liberal Party Peter Milobar Kamloops-North Thompson BC Liberal Party Todd Stone Kamloops-South Thompson BC Liberal Party Ben Stewart Kelowna West BC Liberal Party Norm Letnick Kelowna-Lake Country BC Liberal Party Renee Merrifield Kelowna-Mission BC Liberal Party Tom Shypitka Kootenay East BC Liberal Party Hon. Katrine Conroy Kootenay West BC NDP Hon. John Horgan Langford-Juan de Fuca BC NDP Andrew Mercier Langley BC NDP Megan Dykeman Langley East BC NDP Bob D'Eith Maple Ridge-Mission BC NDP Hon. -

Official Report of Debates (Hansard)

First Session, 42nd Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday, March 1, 2021 Afernoon Sitting Issue No. 16 THE HONOURABLE RAJ CHOUHAN, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC First Session, 42nd Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Raj Chouhan EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Minister of Advanced Education and Skills Training...........................................................................................................Hon. Anne Kang Minister of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries......................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General and Minister Responsible for Housing .............................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ....................................................................................................................Hon. Mitzi Dean Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. Katrina Chen Minister of Citizens’ Services.....................................................................................................................................................Hon. -

March 1, 2021 Dr. Bonnie Henry Provincial Health Officer Ministry Of

March 1, 2021 Dr. Bonnie Henry Provincial Health Officer Ministry of Health PO Box 9648 STN PROV GOVT 1515 Blanshard St. Victoria, B.C. V8W 9P4 Dear Dr. Henry, By way of introduction, we represent a province-wide, cross-section of meeting and event professionals who are working to develop a safe and measured plan for the timely and responsible re-opening of our sector to preserve businesses and put people back to work. The plan is designed to support and ensure compatibility with the Province’s COVID-19 mitigation objectives and to be part of the early phase of a reopening plan for the overall tourism industry in BC. This proposed restart plan specific to business meetings and events is intended for two purposes: 1. To re-activate the meetings & events industry, which has virtually been shut down since March with hundreds of companies closed and thousands of people out of work 2. To allow venues and professional organizers to conduct safe, in-person meetings & events that will re-engage our workforce and stimulate creativity, innovation and community building. Based on research, evidence, best-practices, and specific health and safety protocols, we believe that slowly and carefully re-starting the BC meetings & events sector can be achieved in compliance with PHO directives that ensure the protection and well-being of attendees, employees and suppliers. Until recent restrictions were imposed in December, meetings and events for up to 50 attendees were permitted under public health orders. Over an eight month period leading up to December 2020, evidence suggests that business meetings and events can be held safely when health and safety protocols are successfully implemented in the planning and operations of these gatherings. -

BC Today – Daily Report January 27, 2021 Today in B.C

BC Today – Daily Report January 27, 2021 Quotation of the day “Just plain nonsense.” Liberal Public Safety critic Mike Morris is skeptical of the savings the NDP government says B.C. drivers will see under ICBC’s new no-fault model, launching in May. Today in B.C. Written by Shannon Waters On the schedule The house is adjourned until March 1. B.C.’s natural resource ministers will participate in a roundtable discussion at the virtual BC Natural Resources Forum this afternoon, sharing their thoughts on the “pivotal role” the industries will play “in restoring the province’s economic prosperity.” B.C. boasts ‘most robust’ provincial response to Covid: report British Columbia has committed more of its GDP to pandemic spending than any other province by far, according to a new report from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. The left-leaning think tank pegs B.C.’s pandemic expenditures through 2020 at nearly three per cent of the province’s 2019 GDP — double Quebec’s commitment of 1.5 per cent of the province’s GDP and well ahead of second-place Manitoba, which earmarked two per cent of its 2019 GDP to pandemic support measures. Direct pandemic spending measures in B.C. totalled $10,300 per person, according to CCPA, and while just 16 per cent is coming from provincial coffers, the provincial government is still contributing more to that figure than any of its counterparts. By contrast, Alberta — which has received the most federal funding per capita of all the provinces — chipped in just seven per cent of its $11,200 in per person pandemic spending.