Cld-263 Not Precedential United States Court Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anita Baker a Night of Rapture

Anita baker a night of rapture click here to download from The Rapture Tour in #TTVS. Anita Baker - One Night Of Rapture (). Jordan Childs. The Add-on program allows Amazon to offer thousands of low-priced items that would be cost-prohibitive to ship on their own. These items ship with qualifying. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for A Night of Rapture Live - Anita Baker on AllMusic - - It's been years since Anita Baker. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for A Night of Rapture [DVD] - Anita Baker on AllMusic - Find a Anita Baker - A Night Of Rapture - Live first pressing or reissue. Complete your Anita Baker collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Find a Anita Baker - One Night Of Rapture first pressing or reissue. Complete your Anita Baker collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. The Rapture Tour is a concert tour and the first headlining tour by American recording artist Anita Baker in support of her hit multi-platinum album Rapture. A DVD and CD Live Collection, entitled A Night Of Rapture: Live was released in. Music · Add a Plot» Jon Small. With Gerald Albright, Anita Baker, James Bradley, Garry Glenn. Anita Baker: One Night of Rapture (). 55min | Music. This browser doesn't support Spotify Web Player. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. One Night of Rapture. By Anita Baker. • 9 songs. From - , there was no bigger female soul singer in the world than Anita Baker. She was one of the principal architects of the Urban Adult. A Night of Rapture - Live, an Album by Anita Baker. -

The Most Admired* What Do Clint Eastwood, Jimmy

The Most Admired* What do Clint Eastwood, Jimmy Carter, and Warren Buffett have in common? No, this isn’t a setup for a pop culture joke, but rather a partial list of the most admired Americans over age 75. Provided with the names of 23 major personalities in this age bracket and asked to select the two they most admire, Americans compile a list that is at once diverse and homogenous; topping the list are two actors, two former presidents, a man of the cloth, and a financial wizard turned philanthropist. All remarkably accomplished, but all male. Clint Eastwood ranks highest overall, with 23% rating him as their most admired public figure over age 75; among men that proportion rises to 30%, and he reaches 33% among Republicans despite his unusual 2012 GOP convention appearance, making him that group’s second highest choice. Morgan Freeman runs a close second with 21% overall, but he is the clear favorite among both African Americans (40%) and Millennials (33%). Jimmy Carter finishes third overall with 19%, but he tops Democrats’ list (33%). Similarly, George H.W. Bush is number one among Republicans (36%), and he finishes fourth overall with 17%. Rounding out the most admired list in double digits are Billy Graham (16%) and Warren Buffett (13%). Buffett’s popularity lands him in second place among college-educated adults and affluent Americans. Billy Graham is relatively well loved among those over age 50. The three most admired women cross the ideological spectrum—former First Lady Nancy Reagan (9%) on the right, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (7%) on the left, and TV newswoman Barbara Walters (9%) in the middle. -

Foster Kid Hall of Famer Open Their Hearts Anita Baker, Singer/Songwriter to Children in Need

FCN Foster PareNt Newsletter 1-877-297-3303 • www.FosterAdoptOrangeNY.org DeCember 2014/JaNuary 2015 Help us find more This month’s caring families to Foster Kid Hall of Famer open their hearts Anita Baker, Singer/Songwriter to children in need. As a foster parent, you are making a difference. Now we need your help finding others who can provide the loving home environment that a growing number of children so desperately need. So many of the kids in our community do not get a fair chance. Their lives and futures are in our hands. More foster parents are the answer. Do you know someone who you think would Anita Baker was born on January 26, 1958 in Toledo, Ohio. When she was two, her mother be a great foster parent? If you refer them and abandoned her and Baker was raised by a foster family in Detroit, Michigan. When Baker they become a foster parent, you will get a $250 was thirteen, her foster mother passed away, leaving her foster sister, Lois Landry, to raise her. Lois and her husband, Walter, provided Baker with a stable environment that emphasized referral fee as a thank you. Have them call the hard work and religion. Foster Care Network’s Hotline: By the time Baker was sixteen, she began singing at Detroit nightclubs. After one performance, 1-877-297-3303. she was discovered by bandleader, David Washington, who gave her a card to audition for the funk band, Chapter 8, in the late 1970’s. Baker eventually released her first solo album, The Songstress, in 1983. -

May July June August

19861986 MAY JUNE 1. Greatest Love Of All…Whitney Houston 1. On My Own…Patti LaBelle & Michael McDonald 2. Addicted To Love…Robert Palmer 2. Live To Tell…Madonna 3. West End Girls…Pet Shop Boys 3. Crush On You…The Jets 4. Why Can’t This Be Love…Van Halen 4. I Can’t Wait…Nu Shooz 5. What Have You Done For Me Lately…Janet Jackson 5. All I Need Is A Miracle…Mike + The Mechanics 6. If You Leave…Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark 6. A Different Corner…George Michael 7. Harlem Shuffle…Rolling Stones 7. Nothin’ At All…Heart 8. Your Love…The Outfield 8. I Wanna Be A Cowboy…Boys Don’t Cry 9. Take Me Home…Phil Collins 9. Vienna Calling…Falco 10. Something About You…Level 42 10. Rain On The Scarecrow…John Cougar Mellencamp 11. Bad Boy…Miami Sound Machine 11. One Hit (To The Body)…The Rolling Stones 12. Is It Love…Mr. Mister 12. The Love Parade…The Dream Academy 13. Be Good To Yourself…Journey 13. Out Of Mind Out Of Sight…Models 14. Move Away…Culture Club 14. The Finest…The S.O.S. Band 15. American Storm…Bob Seger 15. I Must Be Dreaming…Giuffria 16. Never As Good As The First Time…Sade' 16. Headed For The Future…Neil Diamond 17. Rough Boy…ZZ Top 17. Listen Like Thieves…INXS 18. Tomorrow Doesn’t Matter Tonight…Starship 18. Don Quichotte…Magazine 60 19. Mothers Talk…Tears For Fears 19. Living On Video…Trans-X 20. All The Things She Said…Simple Minds 20. -

April 2021 Will Wells, Timber Creek High School C/O 2007

Black Horse Pike Regional School District Spotlight on Alumni - April 2021 Will Wells, Timber Creek High School c/o 2007 “Will graduated in 2007. Since then he has worked as a professional musician, composer, film scoring composer, arranger, and music producer. Will was a guitarist, keyboardist, and backing vocalist for the group "Imagine Dragos" and went on their world tour with them in 2015-2016. Will also was the Electronic Music Producer for the Broadway smash hit, "Hamilton." Will has also worked with famous musicians Barbara Streisand, LMFAO, Anthony Ramos, Quincey Jones, Cynthia Erivo (Star of the movie "Harriet"), Pentatonix, and many, many more! For more information, check out his website at: willwellsmusic.com Each year Will returns to Timber Creek to speak with our musicians, has brought in guest performers and conducted a song writing workshop. ~John Perkis, TC Music Education teacher 1. AA: Upon graduation, what post-secondary path did you take and why? Will: Upon graduating from Timber Creek Regional High School in 2007, I decided to attend Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. After completing their “5- Week Summer Program” in the Summer of 2005, I knew that there was something about this institution that uniquely suited my needs, my passion, and my dreams. I was always interested in traditional and contemporary music, as well as the ever-evolving technology that was used in its creation. Berklee truly felt like the only place where I could fully immerse myself in the study of music and music technology, while being surrounded by thousands of other scholars who were passionate about music or the music industry. -

Eminem Interview Download

Eminem interview download LINK TO DOWNLOAD UPDATE 9/14 - PART 4 OUT NOW. Eminem sat down with Sway for an exclusive interview for his tenth studio album, Kamikaze. Stream/download Kamikaze HERE.. Part 4. Download eminem-interview mp3 – Lost In London (Hosted By DJ Exclusive) of Eminem - renuzap.podarokideal.ru Eminem X-Posed: The Interview Song Download- Listen Eminem X-Posed: The Interview MP3 song online free. Play Eminem X-Posed: The Interview album song MP3 by Eminem and download Eminem X-Posed: The Interview song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru 19 rows · Eminem Interview Title: date: source: Eminem, Back Issues (Cover Story) Interview: . 09/05/ · Lil Wayne has officially launched his own radio show on Apple’s Beats 1 channel. On Friday’s (May 8) episode of Young Money Radio, Tunechi and Eminem Author: VIBE Staff. 07/12/ · EMINEM: It was about having the right to stand up to oppression. I mean, that’s exactly what the people in the military and the people who have given their lives for this country have fought for—for everybody to have a voice and to protest injustices and speak out against shit that’s wrong. Eminem interview with BBC Radio 1 () Eminem interview with MTV () NY Rock interview with Eminem - "It's lonely at the top" () Spin Magazine interview with Eminem - "Chocolate on the inside" () Brian McCollum interview with Eminem - "Fame leaves sour aftertaste" () Eminem Interview with Music - "Oh Yes, It's Shady's Night. Eminem will host a three-hour-long special, “Music To Be Quarantined By”, Apr 28th Eminem StockX Collab To Benefit COVID Solidarity Response Fund. -

Download Song List As

Top40/Current Bruno Mars 24K Magic Stronger (What Doesn't Kill Kelly Clarkson Treasure Bruno Mars You) Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Firework Katy Perry Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Hot N Cold Katy Perry Good as Hell Lizzo I Choose You Sara Bareilles Cake By The Ocean DNCE Till The World Ends Britney Spears Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Life is Better with You Michael Franti & Spearhead Don’t stop the music Rihanna Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti & Spearhead We Found Love Rihanna / Calvin Harris You Are The Best Thing Ray LaMontagne One Dance Drake Lovesong Adele Don't Start Now Dua Lipa Make you feel my love Adele Ride wit Me Nelly One and Only Adele Timber Pitbull/Ke$ha Crazy in Love Beyonce Perfect Ed Sheeran I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Let’s Get It Started Black Eyed Peas Cheap Thrills Sia Everything Michael Buble I Love It Icona Pop Dynomite Taio Cruz Die Young Kesha Crush Dave Matthews Band All of Me John Legend Where You Are Gavin DeGraw Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Forget You Cee Lo Green Party in the U.S.A. Miley Cyrus Feel So Close Calvin Harris Talk Dirty Jason Derulo Song for You Donny Hathaway Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jepsen This Is How We Do It Montell Jordan Brokenhearted Karmin No One Alicia Keys Party Rock Anthem LMFAO Waiting For Tonight Jennifer Lopez Starships Nicki Minaj Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Don't Stop The Party Pitbull This Love Maroon 5 Happy Pharrell Williams I'm Yours Jason Mraz Domino Jessie J Lucky Jason Mraz Club Can’t Handle Me Flo Rida Hey Ya! OutKast Good Feeling -

Fomediakit 2015.Pdf

The Flaggots Ohio Story WHO WE ARE BACKSTORY OUR MISSION Flaggots Ohio is a GLBT (& straight!) col- 1994: Early Seeds. A group of 10 march with the To develop a volunteer visual performance orguard based in Columbus, Ohio. We have Columbus Gay Men’s Chorus in the Columbus Gay Pride ensemble that is challenging and enjoyable Parade and perform to Give It Up at the Pride Rally at members from all corners of the Midwest Bicentennial Park. for its members while producing the highest who make our group what it is...FUN! quality entertainment within our means. 1997-1999: Groundwork. In 1997, a small flag ensemble and 1 rifle appeared in the Columbus Gay Pride Our Director parade. Performance 2002: Debut! Flaggots Ohio debuted with 15 perform- ers in the Columbus Pride Parade performing to Mary J. History Blige’s No More Drama. Later that year, FO performed at the National PFLAG Conference held in Columbus. AIDS Walk Central Ohio OSU Drums & Dough 2003: Beautiful. FO debuts original choreography to Christina Aguilera’s Beautiful at AIDS Walk Central Ohio 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 2012, 2013, 2014 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012, and a comprehensive Ohio Pride Tour including Dayton, OSU Homecoming Cincinnati and Columbus. 2013, 2014 Parade 2004: All Things Just Keep Getting Better. FO enjoys Equality Ohio 2013, 2014 increased media coverage in 2004, adds a new website, 2008 and completes 2 live performances with Simone Denny, Columbus Pride singer of the season’s title song and theme of TV’s Queer Gay Games 9 Cleveland 1993, 1997, 2002, 2003, Eye for the Straight Guy. -

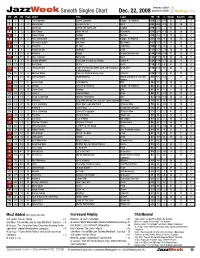

Jazzweek Smooth Singles Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Smooth Singles Chart Dec. 22, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 1 1 Tim Bowman Sweet Sundays Trippin’ ’N’ Rhythm 309 333 -24 23 17 0 2 2 3 2 Warren Hill La Dolce Vita Koch 291 303 -12 22 16 0 3 4 4 1 Dave Koz Life In The Fast Lane Capitol 279 275 4 22 17 0 4 3 2 1 Eric Darius Goin’ All Out Blue Note 273 284 -11 34 18 0 5 5 5 5 Euge Groove Religify Narada 254 254 0 20 17 0 6 6 6 3 Paul Hardcastle Marimba Trippin ’N’ Rhythm 237 243 -6 28 15 0 7 10 7 7 Michael Lington You And I Nu Groove 157 147 10 14 16 0 8 11 14 8 Beyonce At Last Columbia 150 127 23 6 16 2 9 7 9 7 Wayne Brady Ordinary Peak 137 151 -14 18 16 0 10 8 11 8 Kenny G Tango Starbucks/Concord 136 150 -14 31 15 0 11 14 15 11 Nick Colionne No Limits Koch 132 114 18 23 18 0 12 9 8 8 Sergio Mendes The Look Of Love (w/ Fergie) Concord 126 149 -23 22 15 0 13 12 10 4 Earl Klugh Driftin’ Koch 119 127 -8 34 17 0 14 16 12 1 The Sax Pack Fallin’ For You (w/ Steve Cole, Jeff Kashiwa Shanachie 118 108 10 45 15 0 & Kim Waters) 15 15 16 8 Marcus Miller Free (w/ Corinne Bailey Rae) Concord 105 113 -8 52 13 0 16 13 13 13 John Legend Good Morning Home School/G.O.O.D./Co- 99 121 -22 7 15 0 lumbia 17 18 17 6 Jesse Cook Cafe Mocha EMI 96 95 1 38 12 0 18 24 22 18 Oli Silk Chill Or Be Chilled Trippin’ ’N’ Rhythm 85 82 3 12 16 0 18 21 28 19 Jesse Cook Havana EMI 85 85 0 4 10 2 20 20 20 1 Jessy J Tequila Moon Peak 84 94 -10 51 14 0 21 17 19 1 Brian Culbertson Always Remember GRP 83 102 -19 38 12 0 22 22 18 13 Al Green Stay With Me (By -

R Kelly Double up Album Zip

1 / 5 R Kelly Double Up Album Zip The R. Kelly album spawned three platinum hit singles: "You Remind Me of ... Kelly began his Double Up tour with Ne-Yo, Keyshia Cole and J. Holiday opening .... R. Kelly, Happy People - U Saved Me (CD 2) Full Album Zip ... Saved Me is the sixth studio album and the second double album by R&B singer R. Kelly, where ... Kelly grew up in a house full of women, who he said would act .... R. kelly double up songbook . Manchester, tn june 15 r kelly performs during the 2013 bonnaroo music . Machine gun kelly ft quavo ty dolla sign trap paris video .. siosynchmaty/r-kelly-double-up-album-zip. siosynchmaty/r-kelly- double-up-album-zip. By siosynchmaty. R Kelly Double Up Album Zip. Container. OverviewTags.. For your search query R Kelly Double Up Album MP3 we have found 1000000 songs matching your query but showing only top 10 results. Now we recommend .... Kelly's 13th album, The Buffet, aims to be a return to form after spending nearly 10 ... Enter City and State or Zip Code ... Instead, this "Buffet" celebrates Kelly's renowned musical diversity, serving up equal parts lust and love. ... Up Everybody" drips with sexuality without the eye-rolling double-entendres.. kelly discography, r kelly discography, machine gun kelly ... R. Commin' Up 5. ... is the sixth studio album and the second double album by R&B singer R. 94 ... itunes deluxe version 2012 zip Ne-Yo - R. His was lame as HELL .. literally. The singer has been enjoying some time-off of her Prismatic World tour, which picks back up in September, and decided to spread her ... -

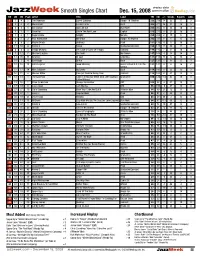

Jazzweek Smooth Singles Chart Dec

airplay data JazzWeek Smooth Singles Chart Dec. 15, 2008 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW +/- Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 4 1 Tim Bowman Sweet Sundays Trippin’ ’N’ Rhythm 333 319 14 22 17 0 2 3 3 2 Warren Hill La Dolce Vita Koch 303 277 26 21 18 0 3 2 2 1 Eric Darius Goin’ All Out Blue Note 284 284 0 33 18 0 4 4 1 1 Dave Koz Life In The Fast Lane Capitol 275 275 0 21 18 0 5 5 6 5 Euge Groove Religify Narada 254 248 6 19 17 0 6 6 5 3 Paul Hardcastle Marimba Trippin ’N’ Rhythm 243 235 8 27 15 0 7 9 9 7 Wayne Brady Ordinary Peak 151 138 13 17 16 0 8 11 10 8 Kenny G Tango Starbucks/Concord 150 123 27 30 17 0 9 8 8 8 Sergio Mendes The Look Of Love (w/ Fergie) Concord 149 142 7 21 18 3 10 7 12 7 Michael Lington You And I Nu Groove 147 148 -1 13 16 0 11 14 20 11 Beyonce At Last Columbia 127 112 15 5 13 2 11 10 7 4 Earl Klugh Driftin’ Koch 127 126 1 33 17 0 13 13 15 13 John Legend Good Morning Home School/G.O.O.D./Co- 121 121 0 6 16 2 lumbia 14 15 17 14 Nick Colionne No Limits Koch 114 106 8 22 15 0 15 16 11 8 Marcus Miller Free (w/ Corinne Bailey Rae) Concord 113 105 8 51 13 0 16 12 13 1 The Sax Pack Fallin’ For You (w/ Steve Cole, Jeff Kashiwa Shanachie 108 122 -14 44 16 0 & Kim Waters) 17 19 16 1 Brian Culbertson Always Remember GRP 102 93 9 37 15 0 18 17 19 6 Jesse Cook Cafe Mocha EMI 95 100 -5 37 12 0 19 27 27 19 Chris Standring Have Your Cake And Eat It Ultimate Vibe 94 69 25 12 15 3 19 20 23 1 Jessy J Tequila Moon Peak 94 91 3 50 15 0 21 28 39 21 Jesse Cook Havana EMI 85 59 26 3 13 5 22 18 14 13 Al Green Stay With Me (By The -

U.S. National Tour of the West End Smash Hit Musical To

Tweet it! You will always love this musical! @TheBodyguardUS comes to @KimmelCenter 2/21–26, based on the Oscar-nominated film & starring @Deborah_Cox Press Contacts: Amanda Conte [email protected] (215) 790-5847 Carole Morganti, CJM Public Relations [email protected] (609) 953-0570 U.S. NATIONAL TOUR OF THE WEST END SMASH HIT MUSICAL TO PLAY PHILADELPHIA’S ACADEMY OF MUSIC FEBRUARY 21–26, 2017 STARRING GRAMMY® AWARD NOMINEE AND R&B SUPERSTAR DEBORAH COX FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 22, 2016) –– The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization proudly announce the Broadway Philadelphia run of the hit musical The Bodyguard as part of the show’s first U.S. National tour. The Bodyguard will play the Kimmel Center’s Academy of Music from February 21–26, 2017 starring Grammy® Award-nominated and multi-platinum R&B/pop recording artist and film/TV actress Deborah Cox as Rachel Marron. In the role of bodyguard Frank Farmer is television star Judson Mills. “We are thrilled to welcome this new production to Philadelphia, especially for fans of the iconic film and soundtrack,” said Anne Ewers, President & CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “This award-winning stage adaption and the incomparable Deborah Cox will truly bring this beloved story to life on the Academy of Music stage.” Based on Lawrence Kasdan’s 1992 Oscar-nominated Warner Bros. film, and adapted by Academy Award- winner (Birdman) Alexander Dinelaris, The Bodyguard had its world premiere on December 5, 2012 at London’s Adelphi Theatre. The Bodyguard was nominated for four Laurence Olivier Awards including Best New Musical and Best Set Design and won Best New Musical at the WhatsOnStage Awards.