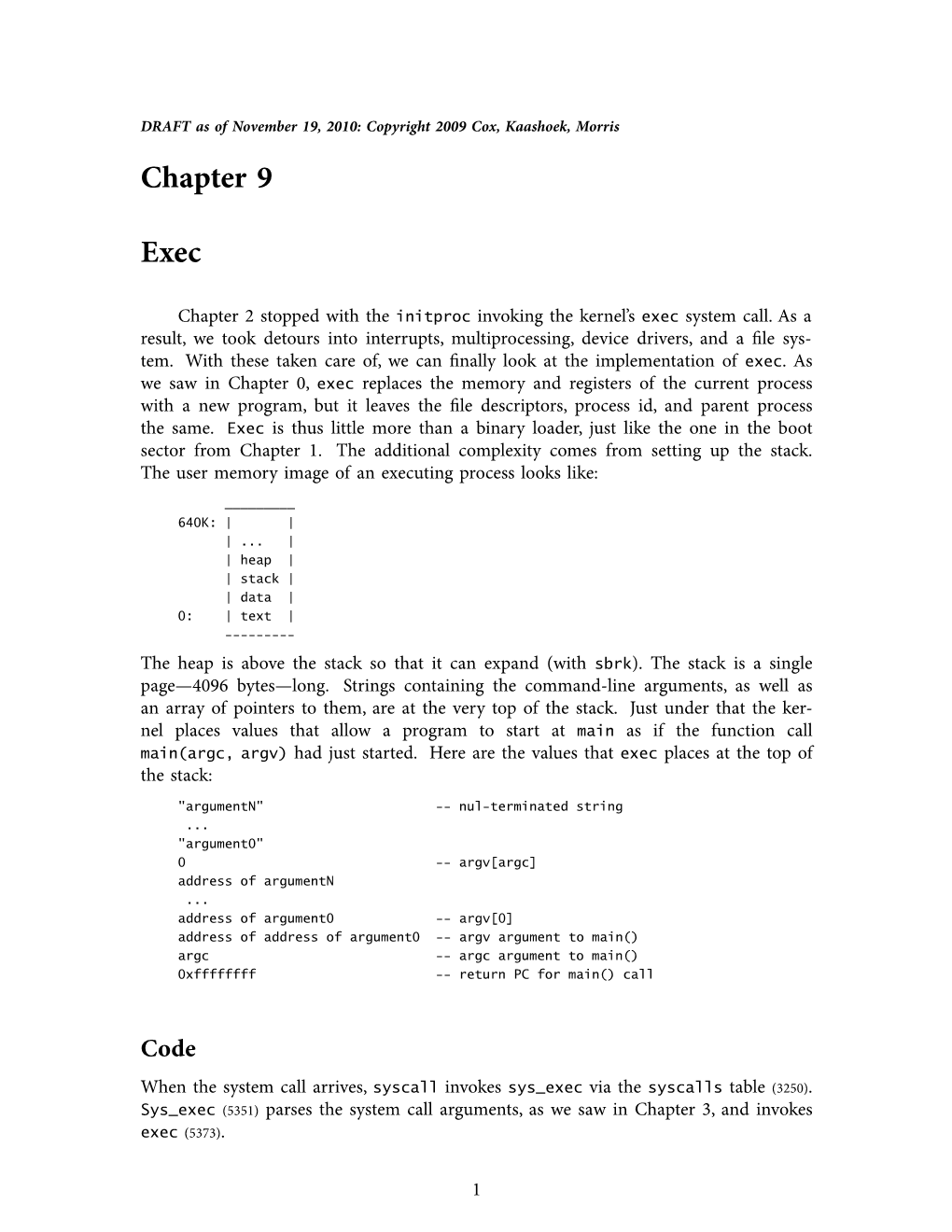

Chapter 9 Exec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Process and Memory Management Commands

Process and Memory Management Commands This chapter describes the Cisco IOS XR software commands used to manage processes and memory. For more information about using the process and memory management commands to perform troubleshooting tasks, see Cisco ASR 9000 Series Aggregation Services Router Getting Started Guide. • clear context, on page 2 • dumpcore, on page 3 • exception coresize, on page 6 • exception filepath, on page 8 • exception pakmem, on page 12 • exception sparse, on page 14 • exception sprsize, on page 16 • follow, on page 18 • monitor threads, on page 25 • process, on page 29 • process core, on page 32 • process mandatory, on page 34 • show context, on page 36 • show dll, on page 39 • show exception, on page 42 • show memory, on page 44 • show memory compare, on page 47 • show memory heap, on page 50 • show processes, on page 54 Process and Memory Management Commands 1 Process and Memory Management Commands clear context clear context To clear core dump context information, use the clear context command in the appropriate mode. clear context location {node-id | all} Syntax Description location{node-id | all} (Optional) Clears core dump context information for a specified node. The node-id argument is expressed in the rack/slot/module notation. Use the all keyword to indicate all nodes. Command Default No default behavior or values Command Modes Administration EXEC EXEC mode Command History Release Modification Release 3.7.2 This command was introduced. Release 3.9.0 No modification. Usage Guidelines To use this command, you must be in a user group associated with a task group that includes appropriate task IDs. -

Command Line Interface Specification Windows

Command Line Interface Specification Windows Online Backup Client version 4.3.x 1. Introduction The CloudBackup Command Line Interface (CLI for short) makes it possible to access the CloudBackup Client software from the command line. The following actions are implemented: backup, delete, dir en restore. These actions are described in more detail in the following paragraphs. For all actions applies that a successful action is indicated by means of exit code 0. In all other cases a status code of 1 will be used. 2. Configuration The command line client needs a configuration file. This configuration file may have the same layout as the configuration file for the full CloudBackup client. This configuration file is expected to reside in one of the following folders: CLI installation location or the settings folder in the CLI installation location. The name of the configuration file must be: Settings.xml. Example: if the CLI is installed in C:\Windows\MyBackup\, the configuration file may be in one of the two following locations: C:\Windows\MyBackup\Settings.xml C:\Windows\MyBackup\Settings\Settings.xml If both are present, the first form has precedence. Also the customer needs to edit the CloudBackup.Console.exe.config file which is located in the program file directory and edit the following line: 1 <add key="SettingsFolder" value="%settingsfilelocation%" /> After making these changes the customer can use the CLI instruction to make backups and restore data. 2.1 Configuration Error Handling If an error is found in the configuration file, the command line client will issue an error message describing which value or setting or option is causing the error and terminate with an exit value of 1. -

Process Management

Princeton University Computer Science 217: Introduction to Programming Systems Process Management 1 Goals of this Lecture Help you learn about: • Creating new processes • Waiting for processes to terminate • Executing new programs • Shell structure Why? • Creating new processes and executing new programs are fundamental tasks of many utilities and end-user applications • Assignment 7… 2 System-Level Functions As noted in the Exceptions and Processes lecture… Linux system-level functions for process management Function Description exit() Terminate the process fork() Create a child process wait() Wait for child process termination execvp() Execute a program in current process getpid() Return the process id of the current process 3 Agenda Creating new processes Waiting for processes to terminate Executing new programs Shell structure 4 Why Create New Processes? Why create a new process? • Scenario 1: Program wants to run an additional instance of itself • E.g., web server receives request; creates additional instance of itself to handle the request; original instance continues listening for requests • Scenario 2: Program wants to run a different program • E.g., shell receives a command; creates an additional instance of itself; additional instance overwrites itself with requested program to handle command; original instance continues listening for commands How to create a new process? • A “parent” process forks a “child” process • (Optionally) child process overwrites itself with a new program, after performing appropriate setup 5 fork System-Level -

Attacker Antics Illustrations of Ingenuity

ATTACKER ANTICS ILLUSTRATIONS OF INGENUITY Bart Inglot and Vincent Wong FIRST CONFERENCE 2018 2 Bart Inglot ◆ Principal Consultant at Mandiant ◆ Incident Responder ◆ Rock Climber ◆ Globetrotter ▶ From Poland but live in Singapore ▶ Spent 1 year in Brazil and 8 years in the UK ▶ Learning French… poor effort! ◆ Twitter: @bartinglot ©2018 FireEye | Private & Confidential 3 Vincent Wong ◆ Principal Consultant at Mandiant ◆ Incident Responder ◆ Baby Sitter ◆ 3 years in Singapore ◆ Grew up in Australia ©2018 FireEye | Private & Confidential 4 Disclosure Statement “ Case studies and examples are drawn from our experiences and activities working for a variety of customers, and do not represent our work for any one customer or set of customers. In many cases, facts have been changed to obscure the identity of our customers and individuals associated with our customers. ” ©2018 FireEye | Private & Confidential 5 Today’s Tales 1. AV Server Gone Bad 2. Stealing Secrets From An Air-Gapped Network 3. A Backdoor That Uses DNS for C2 4. Hidden Comment That Can Haunt You 5. A Little Known Persistence Technique 6. Securing Corporate Email is Tricky 7. Hiding in Plain Sight 8. Rewriting Import Table 9. Dastardly Diabolical Evil (aka DDE) ©2018 FireEye | Private & Confidential 6 AV SERVER GONE BAD Cobalt Strike, PowerShell & McAfee ePO (1/9) 7 AV Server Gone Bad – Background ◆ Attackers used Cobalt Strike (along with other malware) ◆ Easily recognisable IOCs when recorded by Windows Event Logs ▶ Random service name – also seen with Metasploit ▶ Base64-encoded script, “%COMSPEC%” and “powershell.exe” ▶ Decoding the script yields additional PowerShell script with a base64-encoded GZIP stream that in turn contained a base64-encoded Cobalt Strike “Beacon” payload. -

Powershell Integration with Vmware View 5.0

PowerShell Integration with VMware® View™ 5.0 TECHNICAL WHITE PAPER PowerShell Integration with VMware View 5.0 Table of Contents Introduction . 3 VMware View. 3 Windows PowerShell . 3 Architecture . 4 Cmdlet dll. 4 Communication with Broker . 4 VMware View PowerCLI Integration . 5 VMware View PowerCLI Prerequisites . 5 Using VMware View PowerCLI . 5 VMware View PowerCLI cmdlets . 6 vSphere PowerCLI Integration . 7 Examples of VMware View PowerCLI and VMware vSphere PowerCLI Integration . 7 Passing VMs from Get-VM to VMware View PowerCLI cmdlets . 7 Registering a vCenter Server . .. 7 Using Other VMware vSphere Objects . 7 Advanced Usage . 7 Integrating VMware View PowerCLI into Your Own Scripts . 8 Scheduling PowerShell Scripts . 8 Workflow with VMware View PowerCLI and VMware vSphere PowerCLI . 9 Sample Scripts . 10 Add or Remove Datastores in Automatic Pools . 10 Add or Remove Virtual Machines . 11 Inventory Path Manipulation . 15 Poll Pool Usage . 16 Basic Troubleshooting . 18 About the Authors . 18 TECHNICAL WHITE PAPER / 2 PowerShell Integration with VMware View 5.0 Introduction VMware View VMware® View™ is a best-in-class enterprise desktop virtualization platform. VMware View separates the personal desktop environment from the physical system by moving desktops to a datacenter, where users can access them using a client-server computing model. VMware View delivers a rich set of features required for any enterprise deployment by providing a robust platform for hosting virtual desktops from VMware vSphere™. Windows PowerShell Windows PowerShell is Microsoft’s command line shell and scripting language. PowerShell is built on the Microsoft .NET Framework and helps in system administration. By providing full access to COM (Component Object Model) and WMI (Windows Management Instrumentation), PowerShell enables administrators to perform administrative tasks on both local and remote Windows systems. -

Linux-PATH.Pdf

http://www.linfo.org/path_env_var.html PATH Definition PATH is an environmental variable in Linux and other Unix-like operating systems that tells the shell which directories to search for executable files (i.e., ready-to-run programs ) in response to commands issued by a user. It increases both the convenience and the safety of such operating systems and is widely considered to be the single most important environmental variable. Environmental variables are a class of variables (i.e., items whose values can be changed) that tell the shell how to behave as the user works at the command line (i.e., in a text-only mode) or with shell scripts (i.e., short programs written in a shell programming language). A shell is a program that provides the traditional, text-only user interface for Unix-like operating systems; its primary function is to read commands that are typed in at the command line and then execute (i.e., run) them. PATH (which is written with all upper case letters) should not be confused with the term path (lower case letters). The latter is a file's or directory's address on a filesystem (i.e., the hierarchy of directories and files that is used to organize information stored on a computer ). A relative path is an address relative to the current directory (i.e., the directory in which a user is currently working). An absolute path (also called a full path ) is an address relative to the root directory (i.e., the directory at the very top of the filesystem and which contains all other directories and files). -

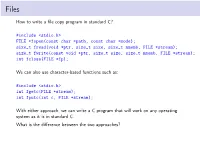

How to Write a File Copy Program in Standard C? #Include <Stdio.H>

Files How to write a file copy program in standard C? #include <stdio.h> FILE *fopen(const char *path, const char *mode); size_t fread(void *ptr, size_t size, size_t nmemb, FILE *stream); size_t fwrite(const void *ptr, size_t size, size_t nmemb, FILE *stream); int fclose(FILE *fp); We can also use character-based functions such as: #include <stdio.h> int fgetc(FILE *stream); int fputc(int c, FILE *stream); With either approach, we can write a C program that will work on any operating system as it is in standard C. What is the difference between the two approaches? /* lab/stdc-mycp.c */ /* appropriate header files */ #define BUF_SIZE 65536 int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { FILE *src, *dst; size_t in, out; char buf[BUF_SIZE]; int bufsize; if (argc != 4) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s <buffer size> <src> <dest>\n", argv[0]); exit(1); } bufsize = atoi(argv[1]); if (bufsize > BUF_SIZE) { fprintf(stderr,"Error: %s: max. buffer size is %d\n",argv[0], BUF_SIZE); exit(1); } src = fopen(argv[2], "r"); if (NULL == src) exit(2); dst = fopen(argv[3], "w"); if (dst < 0) exit(3); while (1) { in = fread(buf, 1, bufsize, src); if (0 == in) break; out = fwrite(buf, 1, in, dst); if (0 == out) break; } fclose(src); fclose(dst); exit(0); } POSIX/Unix File Interface The system call interface for files in POSIX systems like Linux and MacOSX. A file is a named, ordered stream of bytes. I open(..) Open a file for reading or writing. Also allows a file to be locked providing exclusive access. I close(..) I read(..) The read operation is normally blocking. -

Operating System Lab Manual

OPERATING SYSTEM LAB MANUAL BASICS OF UNIX COMMANDS Ex.No:1.a INTRODUCTION TO UNIX AIM: To study about the basics of UNIX UNIX: It is a multi-user operating system. Developed at AT & T Bell Industries, USA in 1969. Ken Thomson along with Dennis Ritchie developed it from MULTICS (Multiplexed Information and Computing Service) OS. By1980, UNIX had been completely rewritten using C langua ge. LINUX: It is similar to UNIX, which is created by Linus Torualds. All UNIX commands works in Linux. Linux is a open source software. The main feature of Linux is coexisting with other OS such as windows and UNIX. STRUCTURE OF A LINUXSYSTEM: It consists of three parts. a)UNIX kernel b) Shells c) Tools and Applications UNIX KERNEL: Kernel is the core of the UNIX OS. It controls all tasks, schedule all Processes and carries out all the functions of OS. Decides when one programs tops and another starts. SHELL: Shell is the command interpreter in the UNIX OS. It accepts command from the user and analyses and interprets them 1 | P a g e BASICS OF UNIX COMMANDS Ex.No:1.b BASIC UNIX COMMANDS AIM: To study of Basic UNIX Commands and various UNIX editors such as vi, ed, ex and EMACS. CONTENT: Note: Syn->Syntax a) date –used to check the date and time Syn:$date Format Purpose Example Result +%m To display only month $date+%m 06 +%h To display month name $date+%h June +%d To display day of month $date+%d O1 +%y To display last two digits of years $date+%y 09 +%H To display hours $date+%H 10 +%M To display minutes $date+%M 45 +%S To display seconds $date+%S 55 b) cal –used to display the calendar Syn:$cal 2 2009 c)echo –used to print the message on the screen. -

Path Howto Path Howto

PATH HOWTO PATH HOWTO Table of Contents PATH HOWTO..................................................................................................................................................1 Esa Turtiainen [email protected].......................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 2. Copyright.............................................................................................................................................1 3. General.................................................................................................................................................1 4. Init........................................................................................................................................................1 5. Login....................................................................................................................................................1 6. Shells....................................................................................................................................................1 7. Changing user ID.................................................................................................................................1 8. Network servers...................................................................................................................................1 -

System Calls & Signals

CS345 OPERATING SYSTEMS System calls & Signals Panagiotis Papadopoulos [email protected] 1 SYSTEM CALL When a program invokes a system call, it is interrupted and the system switches to Kernel space. The Kernel then saves the process execution context (so that it can resume the program later) and determines what is being requested. The Kernel carefully checks that the request is valid and that the process invoking the system call has enough privilege. For instance some system calls can only be called by a user with superuser privilege (often referred to as root). If everything is good, the Kernel processes the request in Kernel Mode and can access the device drivers in charge of controlling the hardware (e.g. reading a character inputted from the keyboard). The Kernel can read and modify the data of the calling process as it has access to memory in User Space (e.g. it can copy the keyboard character into a buffer that the calling process has access to) When the Kernel is done processing the request, it restores the process execution context that was saved when the system call was invoked, and control returns to the calling program which continues executing. 2 SYSTEM CALLS FORK() 3 THE FORK() SYSTEM CALL (1/2) • A process calling fork()spawns a child process. • The child is almost an identical clone of the parent: • Program Text (segment .text) • Stack (ss) • PCB (eg. registers) • Data (segment .data) #include <sys/types.h> #include <unistd.h> pid_t fork(void); 4 THE FORK() SYSTEM CALL (2/2) • The fork()is one of the those system calls, which is called once, but returns twice! Consider a piece of program • After fork()both the parent and the child are .. -

When Powerful SAS Meets Powershell

PharmaSUG 2018 - Paper QT-06 ® TM When Powerful SAS Meets PowerShell Shunbing Zhao, Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA Jeff Xia, Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA Chao Su, Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA ABSTRACT PowerShell is an MS Windows-based command shell for direct interaction with an operating system and its task automation. When combining the powerful SAS programming language and PowerShell commands/scripts, we can greatly improve our efficiency and accuracy by removing many trivial manual steps in our daily routine work as SAS programmers. This paper presents five applications we developed for process automation. 1) Automatically convert RTF files in a folder into PDF files, all files or a selection of them. Installation of Adobe Acrobat printer is not a requirement. 2) Search the specific text of interest in all files in a folder, the file format could be RTF or SAS Source code. It is very handy in situations like meeting urgent FDA requests when there is a need to search required information quickly. 3) Systematically back up all existing files including the ones in subfolders. 4) Update the attributes of a selection of files with ease, i.e., change all SAS code and their corresponding output including RTF tables and SAS log in a production environment to read only after database lock. 5) Remove hidden temporary files in a folder. It can clean up and limit confusion while delivering the whole output folder. Lastly, the SAS macros presented in this paper could be used as a starting point to develop many similar applications for process automation in analysis and reporting activities. -

Computer Systems II Behind the 'System(…)' Command Execv Execl

Computer Systems II Execung Processes 1 Behind the ‘system(…)’ Command execv execl 2 1 Recall: system() Example call: system(“mkdir systest”); • mkdir is the name of the executable program • systest is the argument passed to the executable mkdir.c int main(int argc, char * argv[]) { ... // create directory called argv[1] ... } Unix’s execv The system call execv executes a file, transforming the calling process into a new process. ADer a successful execv, there is no return to the calling process. execv(const char * path, const char * argv[]) • path is the full path for the file to be executed • argv is the argument array, starEng with the program name • each argument is a null-terminated string • the first argument is the name of the program • the last entry in argv is NULL 2 system() vs. execv system(“mkdir systest”); mkdir.c int main(int argc, char * argv[]) { ... // create directory called argv[1] ... } char * argv[] = {“/bin/mkdir”, “systest”, NULL}; execv(argv[0], argv); How execv Works (1) pid = 25 pid = 26 Data Resources Data Text Text Stack Stack PCB File PCB char * argv[ ] = {“/bin/ls”, 0}; cpid = 26 cpid = 0 char * argv[ ] = {“/bin/ls”, 0}; <…> <…> int cpid = fork( ); int cpid = fork( ); if (cpid = = 0) { if (cpid = = 0) { execv(argv[0], argv); execv(argv[0], argv); exit(0); exit(0); } } <parent code> <parent code> wait(&cpid); wait(&cpid); /bin/ls UNIX kernel 3 How execv Works (2) pid = 25 pid = 26 Data Resources Text Stack PCB File char * argv[ ] = {“/bin/ls”, 0}; cpid = 26 <…> Exec destroys the int cpid = fork( ); if (cpid = = 0) { process image of the execv(argv[0], argv); calling process.