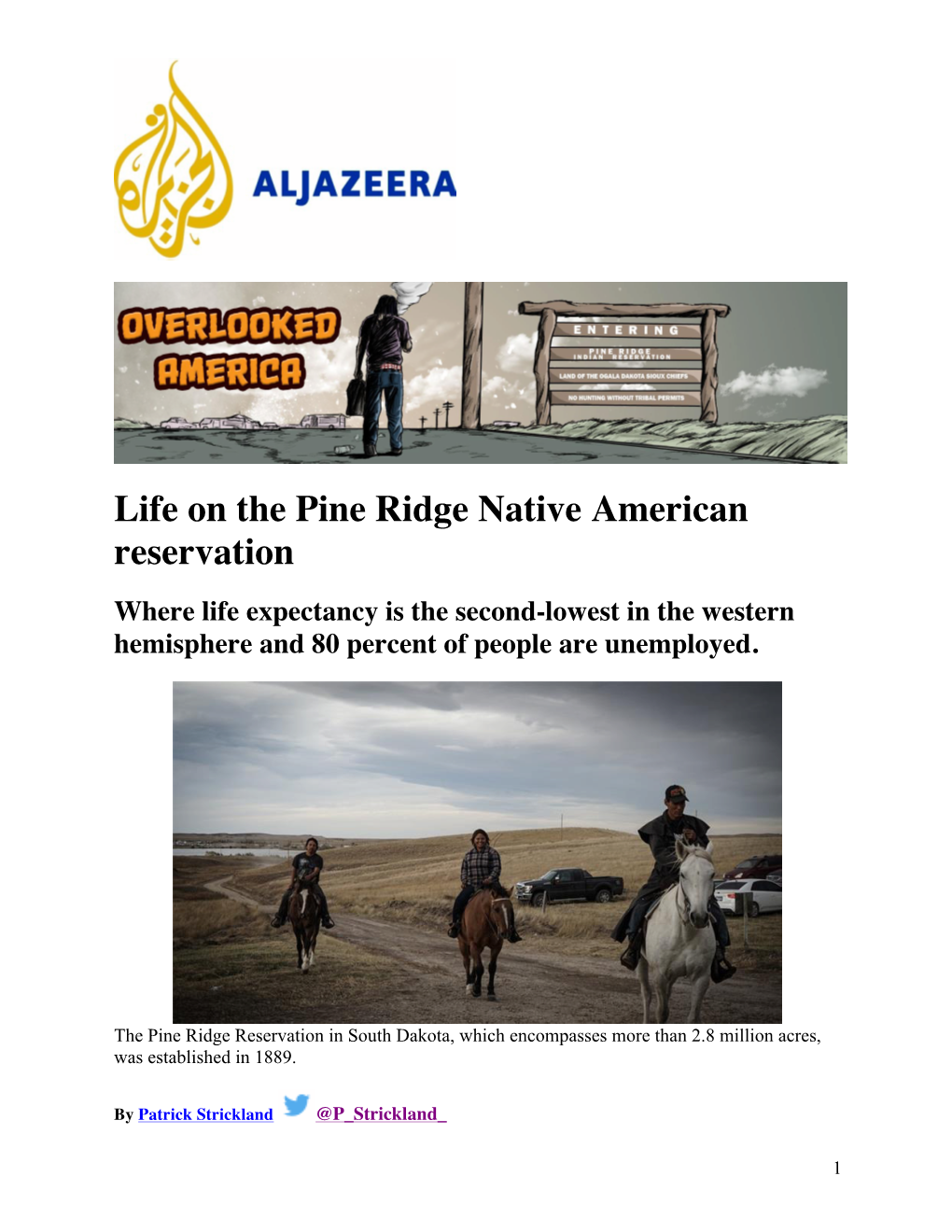

Life on the Pine Ridge Native American Reservation Where Life Expectancy Is the Second-Lowest in the Western Hemisphere and 80 Percent of People Are Unemployed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

His Brothers' Keeper

His Brothers’ Keeper Lawyer Gregory Stanton refuses to let the world ignore the genocide of two million Kampucheans. This is the story of their tragedy and his dedication. By Michael Matza There is a compelling sense of mission about 35-year-old Gregory Howard Stanton, a 1982 graduate of Yale Law School. This past April, Stanton launched a one- man effort he calls the Kampuchean Genocide Project, through which he hopes to raise $300,000 to send researchers and scientists to Southeast Asia to gather evidence that would document—precisely and for posterity—the crimes of the Pol Pot government in Democratic Kampuchea (Cambodia) from April 1975 through the end of 1978. Although it was thrown out of power by a Vietnamese-backed invasion in 1979, the government that was named for Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot still represents Kampuchea as part of a united front in the United Nations. That it does so belies a past that survivors of Khmer Rouge brutalities remember with dread. In the three and a half years that it was in power, the Pol Pot regime is said to have intentionally murdered at least one million Kampucheans and to have imposed conditions of slave labor, starvation, and forced evacuations that resulted in the deaths of more than one million others. In a country of approximately eight million people, one quarter of the population was systematically exterminated through a maniacal program that seemed like the Final Solution writ small. For Greg Stanton, such mind-boggling carnage imposes a personal obligation. “There are people who can become numb to the killing. -

Cinema Invisibile 2014-The Killing-Flyer

cinema LUX cinema invisibile febbraio > maggio 2014 martedì ore 21.00 giovedì ore 18.30 The Killing - Linden, Holder e il caso Larsen The Killing serie tv - USA stagione 1 (2011) + stagione 2 (2012) 13 episodi + 13 episodi Seattle. Una giovane ragazza, Rosie Larsen, viene uccisa. La detective Sarah Linden, nel suo ultimo giorno di lavoro alla omicidi, si ritrova per le mani un caso complicato che non si sente di lasciare al nuovo collega Stephen Holder, incaricato di sostituirla. Nei 26 giorni delle indagini (e nei 26 episodi dell'avvincente serie tv) la città mostra insospettate zone d'ombra: truci rivelazioni e insinuanti sospetti rimbalzano su tutto il contesto cittadino, lacerano la famiglia Larsen (memorabile lo struggimento progressivo di padre, madre e zia) e sconvolgono l'intera comunità non trascurando politici, insegnanti, imprenditori, responsabili di polizia... The Killing vive di atmosfere tese e incombenti e di un ritmo pacato, dal passo implacabile e animato dai continui contraccolpi dell'investigazione, dall'affollarsi di protagonisti saturi di ambiguità con responsabilità sempre più difficili da dissipare. Seattle, con il suo grigiore morale e la sua fitta trama di pioggia, accompagna un'indagine di sofferto coinvolgimento emotivo per il pubblico e per i due detective: lei taciturna e introversa, “incapsulata” nei suoi sgraziati maglioni di lana grossa; lui, dal fascino tenebroso, con un passato di marginalità sociale e un presente tutt’altro che rassicurante. Il tempo dell'indagine lento e prolungato di The Killing sa avvincere e crescere in partecipazione ed angoscia. Linden e Holder (sempre i cognomi nella narrazione!) faticheranno a dipanare il caso e i propri rapporti interpersonali, ma l'alchimia tra una regia impeccabile e un calibrato intreccio sa tenere sempre alta la tensione; fino alla sconvolgente soluzione del giallo, in cui alla beffa del destino, che esalta il cinismo dei singoli e scardina ogni acquiescenza familiare, può far da contraltare solo la toccante compassione per la tragica fine di Rosie. -

Morrow Final Dissertation 20190801

“THAT’S WHY WE ALWAYS FIGHT BACK”: STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AND WOMEN’S RESPONSES ON A NATIVE AMERICAN RESERVATION BY REBECCA L. MORROW DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Assata Zerai, Chair Associate Professor Anna-Maria Marshall Associate Professor Ruby Mendenhall Professor Norman Denzin Professor Robert M. Warrior, University of Kansas ABSTRACT This project explores how women who live on a southern California reservation of the Kumeyaay Nation experience and respond to violence. Using a structural violence lens (Galtung 1969) enables a wider view of the definition of violence to include anything that limits an individual’s capabilities. Because the project used an inductive research method, the focus widened a study of intimate partner and family violence to the restrictions caused by the reservation itself, the dispute over membership and inclusion, and health issues that cause a decrease in life expectancy. From 2012 to 2018, I visited the reservation to participate in activities and interviewed 19 residents. Through my interactions, I found that women deploy resiliency strategies in support of the traditional meaning of Ipai/Tipai. This Kumeyaay word translates to “the people” to indicate that those who are participating are part of the community. By privileging the participants’ understanding of belonging, I found three levels of strategies, which I named inter-resiliency (within oneself), intra-resiliency (within the family or reservation) and inter-resiliency (within the large community of Kumeyaay or Native Americans across the country), but all levels exist within the strength gained from being part of the Ipai/Tipai. -

The Pain Experience of Traditional Crow Indian by Norma Kay

The pain experience of traditional Crow Indian by Norma Kay Krumwiede A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Nursing Montana State University © Copyright by Norma Kay Krumwiede (1996) Abstract: The purpose of this qualitative research study was to explore the pain experience of the traditional Crow Indian people. An understanding of the Crow people's experience of pain is crucial in order to provide quality nursing care to members of this population. As nurse researchers gain understanding of these cultural gaps and report their findings, clinically based nurses will be better equipped to serve and meet the unique needs of the traditional Crow Indian. Ethnographic interviews were conducted with 15 traditional Crow Indians currently living on the reservation in southeastern Montana. The informants identified themselves as traditional utilizing Milligan's (1981) typology. Collection of data occurred through (a) spontaneous interviews, (b) observations, (c) written stories, (d) historical landmarks, and (e) field notes. Spradley's (1979) taxonomic analysis method was used to condense the large amount of data into a taxonomy of concepts. The taxonomy of Crow pain evolved into two indigenous categories of “Good Hurt” and “Bad Hurt”. The Crow view “good hurt” as being embedded in natural life events and ceremonies, rituals and healing. The Crow experience "bad hurt” as emanating from two sources: loss and hardship. The Crow believe that every person will experience both “good hurt” and “bad hurt” sometime during their lifetime. The Crow gain knowledge, wisdom and status as they experience, live through, and learn from painful events throughout their lifetime. -

Tuesday Morning, May 8

TUESDAY MORNING, MAY 8 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Ricky Martin; Giada De Live! With Kelly Stephen Colbert; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Laurentiis. (N) (cc) (TV14) Miss USA contestants. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Rhyming Block. Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Three new nursery rhymes. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Iden- 12/KPTV 12 12 tity Crisis. (cc) (TV14) Positive Living Public Affairs Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Billy Graham Classic Crusades Doctor to Doctor Behind the It’s Supernatural Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) Scenes (cc) (TVG) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (N) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court (N) The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (cc) (TVG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter A fugitive and Criminal Minds The team must Criminal Minds Hotch has a hard CSI: Miami Inside Out. -

Law, Art, and the Killing Jar

Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center Scholarly Works Faculty Scholarship 1993 Law, Art, And The Killing Jar Louise Harmon Touro Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/scholarlyworks Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 79 Iowa L. Rev. 367 (1993) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Law, Art, and the Killing Jart Louise Harnon* Most people think of the law as serious business: the business of keeping the peace, protecting property, regulating commerce, allocating risks, and creating families.' The principal movers and shakers of the law work from dawn to dusk, although they often have agents who work at night. 2 Their business is about the outer world and how we treat each other during the day. Sometimes the law worries about our inner life when determining whether a contract was made5 or what might have prompted a murder,4 but usually the emphasis in the law is on our external conduct and how we wheel and deal with each other. The law turns away from the self; it does not engage in the business of introspection or revelation. t©1994 Louise Harmon *Professor of Law, Jacob D. Fuchsberg Law Center, Touro College. Many thanks to Christine Vincent for her excellent research assistance and to Charles B. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

THE KILLING SEASON a Summer Inside an LAPD Homicide Division

NATIONAL BESTSELLER "Remarkable—great journalism, social commentary, and writing rolled into a fascinating, gripping, and at times heartwrenching story."—Michael Connelly, rwiTiTT^ Author of The Poet and TVunk Music KILLING SEASON \ A SUMMER Ilmdeanlafd homicide division MILE C O RW I N THE KILLING SEASON A Summer Inside an LAPD Homicide Division Miles Corwin FAWCETT CREST • NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reportedto the publisheras "un sold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Fawcett Crest Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright © 1997 by Miles Corwin All rights reservedunder International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by The Ballantine Pub lishingGroup,a division of Random House. Inc., NewYork, and dis tributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited,Toronto. The photographs on insert pages 2-7 and cover photograph by Gary Friedman/Las Angeles Times http://www.randomhouse.com Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97-97106 ISBN 0-449-00291-8 This edition published by arrangement with Simon & Schuster, Inc. Manufactured in the United States ofAmerica First Ballantine Books Edition: May 1998 10 9 8 7 6 5 In memoryofmyfather, Lloyd Corwin Introduction The genesisof this book was a summer night that I spent with a homicide detective in South-Central Los Angeles. I was the crime reporterfor the LosAngeles Times, and I followed the detective in order to write about the changing nature of homi cide in the city. -

Reflections on the Killing of Shaikh Ahmad Yasin

Reflections on the killing of Shaikh Ahmad Yasin By William R. Polk Before a few days ago, few people in the West had ever heard of Shaikh Ahmad Yasin, but among Muslim Arabs he had long been a major figure. Who was he, why was he important, why was he killed and what can be predicted as the aftermath of his death? These are the questions I will address in this article. First, it is important to be clear about the nature of terrorism. Terrorism is a tactic not a “thing” or movement or group that can be attacked. It is, moreover, not confined to any race, religion or national group. It has been employed all over the world throughout history and in recent times has been practiced by the Irish, Basques, French, Italians, Algerians, Libyans, Jewish Zionists, Palestinian Arabs, Sudanese Christians, Tamil Hindus, Tibetan Buddhists and many others. Americans today forget that, when they began their war of independence against the British, terrorism was their favored tactic. Why have so many peoples adopted this tactic? The simple answer is that they are driven to use it because they do not have other means. When political expression is stifled and when enemies have overwhelming power, it is the tactic of last resort. In sum, terrorism is the weapon of the weak. It is, of course, a horrible weapon. All weapons are. That has always been the intent of those who make and use them. A visit to any museum shows the skill with which ancient daggers were designed to inflict the worst possible pain and so to terrify the enemy. -

The Farmington Report: a Conflict of Cultures

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 132 236 UD 016 635 AUTHOR Chin, Laura, Ed.; And Others TITLE The Farmington Report: A Conflict of Cultures. A , Report of the New Mexico Advisory Committee:to the United States Commission on Civil Rights ,INSTITUTION New Mexico State Advisory Committee to the U S. Commission on Civil Rights, Santa Fe. PUB DATE Jul 75 , I NOTE 194p. , ETES PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$10.03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alcoholism; American Indians; *Civil Rights; - Community Attitudes; *Culture Conflict; Economic Factors; Employment Problem; Health Services; Law Enforcement; *Local Governm:nt; Medical,Services; *Navaho; Public Officials; *Reservations (Ipian); Social Factors , IDENTIFIERS *New Mexico (Farmington) ABSTRACT , In response to numerous complaints from Navajo leaders, the New Mexico Advisory Committee undertook this study of the complex social and economic relationships that bind the city of Farmington and the Navajo Reservation. This report examines issues relating to community attitudes; the administration of justice; provisions of health and medical services; alcohol abuse and ,alcoholism; employmept; and economic development on the Navajo Reservation and its real and potential impact On the city of Farmington and San Juan County. From testimony of participants during a three-day open meeting in Farmington and from extensive field investigation, the Advisory Committee has concluded that Native Americans in almost every area suffer from injustice and maltreatment. Recommendations are addressed to local, county, State, and Federal agencies. They include: establishing a human relations committee in Farmington; developing a comprehensive alcohol abuse and alcoholism program; coordination between public and private health facilities to provide adequate services to Navajos; upgrading the community relations program of the Farmington Police Department; affirmative action by private and public employers; and compliance with the "Indian Preference" clause by private employers on the reservations. -

Crow Dog's Case: a Chapter in the Legal History of Tribal Sovereignty

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY School of Law 1989 Crow Dog's Case: A Chapter in the Legal History of Tribal Sovereignty Sidney Harring CUNY School of Law How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/325 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] CROW DOG'S CASE: A CHAPTER IN THE LEGAL HISTORY OF TRIBAL SOVEREIGNTY Sidney L. Harring* By any standard, Ex parte Crow Dog ranks among the most im- portant of the foundational cases in federal Indian law. Moreover, its place in the foundation, as the most important late nineteenth century tribal sovereignty case, means Crow Dog has continuing importance as American Indians, lawyers and scholars call for a new federal Indian law that recognizes tribal sovereignty and a continuing nation-to-nation relationship between the United States and the Indian tribes.' Even within this sovereignty framework, Crow Dog has special meaning. Its compelling story began with the killing of a Brule Sioux chief, Spotted Tail, by Crow Dog, who was later sentenced to hang for the crime. His conviction was reversed by the United States Supreme Court with a strong holding that the Brule had a sovereign right to their own law, leaving the United States courts with no jurisdiction. Felix Cohen, who very nearly originated the field of federal Indian law, refers to the case as "an extreme application of the doctrine of tribal sovereignty." 2 This characterization of the Crow Dog holding has always colored the case, leaving it a kind of legal atrocity, showing the "savage" quality of tribal law, and setting the stage for a succes- sion of doctrinal devices that emphasized tribal "dependency" * Associate Professor of Law, School of Law, City University of New York. -

The “Final Solution”

THE “FINAL SOLUTION” Introduction Although the Nazis came to power in 1933, it wasn’t until the second half of 1941 that Nazi policy began to focus on the annihilation of the Jewish people. This evolution in policy coincided with Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Nazi leaders saw the invasion of the Soviet Union not only as a bid to gain territory that they felt was vital for Germany, but as an ideological struggle. The brutality of the invasion coalesced with racial antisemitism to further radicalize anti-Jewish polices since Jews were seen as the racial and ideological archenemy— especially the stereotype that Jews were the creators and primary agents of Bolshevism. Historians note that on July 31, 1941, Hermann Goering, Hitler’s second in command, sent an official order to Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the security branch of the SS, to authorize a “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.” The exact meaning behind this order is still debated among many Holocaust scholars. Current research shows that mass systematic killing of Jewish men in the newly conquered territory of the Soviet Union began in June, and by August included women and children as well. There is no surviving order by Hitler to expand the murderous activities to encompass all Jews under Nazi control, but most scholars believe such an order was given in the autumn of 1941, or at the latest early in 1942. Even if the exact sequence of events regarding the order is unknown, L5 the fact remains that mass murder continued swiftly, and soon spread to Poland and other European countries.