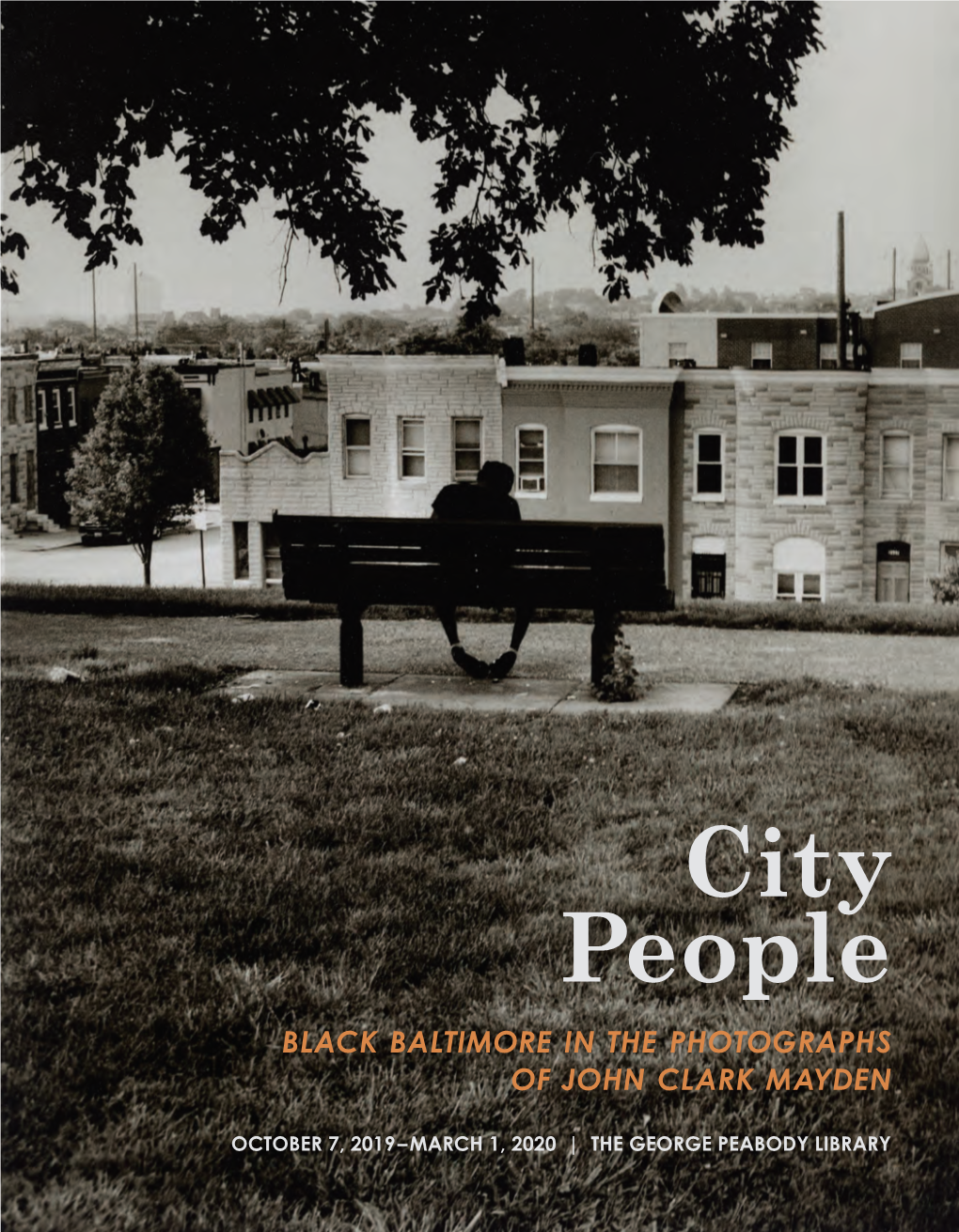

THE GEORGE PEABODY LIBRARY John Clark Mayden, Self-Portrait, Circa 1970

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johns Hopkins in Maryland

Johns Hopkins in Maryland Total Economic Impact: $9.1 Billion in Economic Output, 85,678 Jobs Johns Hopkins Facilities & Operations in Maryland Pennsylvania JHCP Hagerstown Wilmer at Bel Air JHCP Westminster University Center of Northeastern Maryland Health Care & Surgery Center at Green Spring Station / JHCP Water’s Edge JHCP Frederick JHCP Green Spring Station Eldersburg Signature OB/GYN Peabody Preparatory (Towson Campus) Health Care & Surgery Center at White Marsh / JHCP White Marsh See Inset Columbia Signature OB/GYN JHCP Greater Dundalk Howard County General Hospital / JHCP Howard County General Hospital JHCP Howard County JHCP Germantown Columbia Center Baltimore Delaware Applied Physics Laboratory JHCP Fulton JHCP Glen Burnie JHCP Rockville (heart care) JHCP North Montgomery County Campus / JHCP Bethesda Health Care Center at Odenton / JHCP Montgomery Laurel JHCP Odenton Health Care & Surgery Center at Bethesda / JHCP Silver Spring (heart care) JHCP Bethesda (heart care), JHCP Rockledge JHCP Downtown Bethesda Peabody Preparatory (Annapolis Campus) Suburban Hospital / JHCP Suburban Hospital General Surgery JHCP Bowie JHCP Chevy Chase (heart care) at Foxhall JHCP Annapolis Sibley Memorial Hospital / JHCP Sibley Memorial Hospital SAIS Washington / JHCP Washington D.C. Center Ballston Medical Center I Street Chesapeake The Johns Hopkins Hospital Billings Dome in the context of Washington D.C. Bay Baltimore City Virginia Not shown on map: All Children’s Hospital in St. Petersburg, FL JHCP Charles County Southern Maryland Higher Education -

Peabody Computer Music: 46 Years of Looking to the Future

ICMC 2015 – Sept. 25 - Oct. 1, 2015 – CEMI, University of North Texas Peabody Computer Music: 46 Years of Looking to the Future Dr. Geoffrey Wright Dr. McGregor Boyle Mr. Joshua Armenta Peabody Computer Music Peabody Computer Music Peabody Computer Music [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mr. Ryan Woodward Ms. Sunhuimei Xia Peabody Computer Music Peabody Computer Music [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT and tape). In addition, there were compositions by three of her former students: McGregor Boyle, Scott Pender, and Ge- There are many significant firsts in the history of Peabody offrey Wright. In between the performances friends and for- Computer Music (PCM). It is the first electronic and com- mer students of Ivey shared their memories of her–resulting in puter music studio in a conservatory in the United States [1]. a touching tribute to this wonderful composer, teacher, men- Peabody itself is the first conservatory of music in the U.S., tor, and friend. [1] and our parent institution, the Johns Hopkins University, is America’s first research university [2]. For 46 years PCM has been training highly-skilled musi- cians to use computers and technology for composition, per- formance, and music-related research. We work within the context of a conservatory that prizes the great accomplish- ments of the past even as we develop new musical vocabular- ies and techniques for the expressive musician of the future. New dean Fred Bronstein is a vital force in leading the old- est music conservatory in the U.S. into the 21st century [3]. -

Johns Hopkins University Style Guide Contents Introduction Names

JHU Office of Communications Style Guide page 1 Johns Hopkins University Style Guide Contents • Introduction • Names: Johns Hopkins University and its divisions • Style guidelines Introduction These guidelines were compiled by editors in the Office of Communications to encourage consistency and correct usage of terms across the many publications produced by JHU offices. The guidelines draw from The Associated Press Stylebook 2019 and the 17th edition of The Chicago Manual of Style. Written from a Johns Hopkins point of view, the guidelines are intended to complement AP and CMOS and, when those sources disagree, to choose between them. For points not addressed in the university guidelines, AP is the preferred source. For points not listed in AP, use the dictionary it recommends: Webster’s New World College Dictionary. When the dictionary gives two spellings, use the first one; when the dictionary and AP give different spellings, use AP’s. A number of individual JHU publications have their own style sheets, more detailed and directed to handling specialized content. Johns Hopkins Medicine, for example, has posted its Branding and Use of Name Toolkit http://brand.hopkinsmedicine.org/gui/content.asp. The guidelines below will supplement those already existing and will contribute to the effort to bring overall consistency to university publications. Names: Johns Hopkins University and its divisions The Johns Hopkins University/The Johns Hopkins Hospital: The preferred shortened name for Johns Hopkins University is Johns Hopkins, not Hopkins. The acronym JHU can be used as a shortened form in informal or internal communications and to avoid repetition of the Hopkins name. -

Freshman Fellows: Implementing and Assessing a First-Year Primary-Source Research Program

Library Impact Practice Brief Freshman Fellows: Implementing and Assessing a First-Year Primary-Source Research Program Research Team Members: Margaret Burri, Joshua Everett, Heidi Herr, and Jessica Keyes Sheridan Libraries, Johns H opkins Univ ersity July 15, 2021 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Association of Research Libraries 21 Dupont Circle NW, Suite 800, Washington, DC 20036 (202) 296-2296 | ARL.org Issue Libraries spend significant time and money collecting and making Special Collections materials available to researchers. A critical piece of this work is teaching students how to engage with rare and unique materials to answer research questions and make new contributions to knowledge. Five years ago, to give scholars starting their college journey the chance to conduct original research, the Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins University established a Freshman Fellows (FF) program1 that partners first-year students with their own curatorial mentor for a one-year research project. This program graduated its first cohort of four fellows in spring 2020, and the research team designed an assessment project to see how this experience impacted the fellows’ studies and co-curricular activities at Johns Hopkins, as well as the mentors’ approach to the program and their larger work in Special Collections. Additionally, the team realized that the program would benefit from a structured way to review the fellows’ final projects, so we added the development of an assessment rubric (Appendix 4). A former colleague, Steph Gamble, suggested mapping various pedagogical measures, including the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education,2 into a rubric to be used to evaluate the work. -

Teaching by the Book: the Culture of Reading in the George Peabody Library Gabrielle Dean

JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY Teaching by the Book: The Culture of Reading in the George Peabody Library Gabrielle Dean First, there is a gasp or sigh; then the wide-eyed ing Culture in the Nineteenth-Century Library,” viewer slowly circumnavigates the building. In the which examined the intersections of the public George Peabody Library, one of the Johns Hopkins library movement, nineteenth-century book his- University’s rare book libraries, I often witness this tory and popular literature in order to describe the awe-struck response to the architecture. The library culture of reading in nineteenth-century America. interior, made largely of cast iron, illuminated by a I designed this semester-long course with two com- huge skylight and decorated with gilded neo-Gothic plementary aims in mind. and Egyptian elements, was completed in 1878 and First, I wanted to develop a new model for teach- fully expresses the aspirations of the age. It is gaudy ing American literature. Instead of proceeding from and magnificent, and it never fails to impress visitors. a set of texts deemed significant by twenty-first cen- The contents of the library are equally symbolic tury critics, our syllabus drew from the Peabody’s and grand, but less visible. The Peabody first opened collections to gain insight into what was actually to the Baltimore public in 1866 as part of the Pea- purchased, promoted and read in the nineteenth body Institute, an athenaeum-like venture set up by century. Moreover, there was no artificial separa- the philanthropist George Peabody; it originally in- tion between the texts we examined and their mate- cluded a lecture series and an art gallery in addition rial contexts. -

Who-Was-Johns-Hopkins.Pdf

Who was Johns Hopkins? hile previously adopted accounts portray Johns Hopkins as an early abolitionist whose father had freed the family’s enslaved people in the early 1800s, recently discovered records offer strong evidence that Johns Hopkins held enslaved people in his home until at least the mid-1800s. More information about the university’s investigation of this history is available at the Hopkins Retrospective website. Johns Hopkins by Thomas C. Corner oil on canvas, 100 by 58 inches, 1896 The Johns Hopkins Hospital, shown here at the time of its completion in 1889, was considered a municipal and national marvel when it opened. It was believed to be the largest medical center in the country with 17 buildings, 330 beds, 25 physicians and 200 employees. As a Baltimore American headline put it on May 7, 1889, the Hospital’s opening day, “Its Aim Is Noble,” and its service would be “For the Good of All Who Suffer.” Johns Hopkins, the Quaker merchant, banker and businessman, left $7 million in 1873 to create The Johns Hopkins University and The Johns Hopkins Hospital, instructing his trustees to create new models and standards for medical education and health care. He was named for his great-grandmother, Margaret Johns, her last name becoming his first (and confusing people ever since). Considering his wealth a trust, Johns into the fields. At 17, knowing the planta- Hopkins used it for the benefit of tion was not big enough to support his humanity. By 1873, the year of his death, large family, young Johns (that had been Johns Hopkins had outlined his wishes: his great-grandmother’s maiden name) to create a university that was dedicated moved to Baltimore to help his father’s to advanced learning and scientific brother, a wholesale grocer. -

Everything You Wanted to Know About America's First Research University

Everything you wanted to know about America’s first research university Information current as of April 2018 We began by asking big questions. JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY FACT BOOK RESEARCHFIVE FACTS IN ABOUT 24 TIME JOHNS ZONES HOPKINS AND 70 UNIVERSITY COUNTRIES “What are we aiming at?” 1. The university’s graduate programs in 3. It is the leading U.S. academic institution public health, nursing, biomedical in total research and development engineering, medicine, and education are spending. In fiscal year 2016, the university That’s the question Daniel Coit Gilman asked in 1876, considered among the best in the country, performed $2.431 billion in medical, science, and at his inauguration as Johns Hopkins University’s first according to U.S. News & World Report. The engineering research. It has ranked No. 1 in higher president. His answer, in part: “The encouragement master’s and doctoral programs in public health, education research spending for the 38th year in a the graduate program in biomedical engineering, row, according to the National Science Foundation. of research . and the advancement of individual and the master’s program in nursing all rank No. 1. The university also ranks first on the NSF’s list scholars, who by their excellence will advance the sci- The program in internal medicine is tied at No. 1. for federally funded research and development, ences they pursue, and the society where they dwell.” The Doctor of Nursing Practice program is No. 2. spending $2.104 billion in fiscal year 2016 on Gilman believed that teaching and research are The School of Medicine as at No. -

B-967 Peabody Institute Conservatory & George Peabody Library

B-967 Peabody Institute Conservatory & George Peabody Library Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-10-2011 Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No. B-967 Maryland Inventory of EASEMENT Historic Properties Form 1. Name of Property (indicate preferred name) historic Peabody Institute Conservatory and George Peabody Library (preferred) other Peabody Institute Library 2. Location street and number 1 & 17 East Mount Vernon Place not for publication city, town Baltimore vicinity county Baltimore City 3. Owner of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name JHP, Inc. c/o The Johns Hopkins University street and number 3400 N. Charles Street telephone 410-659-8100 city, town Baltimore state Maryland zip code 21218 4. -

Zlatko Tesanovic

Zlatko Tesanovic Zlatko was born in Sarajevo (former Yugoslavia) on August 1, 1956 and passed away on July 26, 2012. InsItute for Quantum Maer, Johns Hopkins-Princeton Posions 1994-2012: Professor, Johns Hopkins University 1990-1994: Associate Professor, Johns Hopkins University 1987-1990: Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University 1987-1988: Director's Postdoctoral Fellow (on leave from JHU), Los Alamos Naonal Laboratory 1985-1987: Postdoctoral Fellow, Harvard University Educaon 1980-1985: Ph.D. in Physics, University of Minnesota 1975-1979: B.Sc. in Physics (Summa cum Laude), University of Sarajevo, former Yugoslavia Fellowships, Awards, Honors Foreign Member, The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and LeLers Fellow, The American Physical Society, Division of Condensed Maer Physics Inaugural Speaker, J. R. Schrieffer Lecture Series, Naonal High MagneIc Field Laboratory, 1997 David and Lucille Packard Foundaon Fellowship, 1988-1994 J. R. Oppenheimer Fellowship, Los Alamos Naonal Laboratory, 1985 (declined) Stanwood Johnston Memorial Fellowship, University of Minnesota, 1984 Shevlin Fellowship, University of Minnesota, 1983 Fulbright Fellowship, US InsItute of Internaonal Educaon, 1980 Zlatko Tesanovic Graduate Students (10) L. Xing (Jacob Haimson Professor, Stanford), I. F. Herbut (Professor, Simon Fraser University, Canada), A. Andreev (Associate Professor, University of Washington), S. Dukan (Professor and Chair of Physics, Goucher College), O. Vafek (Associate Professor, Florida State University and NHMFL), A. Melikyan (Editor, Physical Review B), Andres Concha (Postdoctoral Fellow, Harvard), ValenIn Stanev (Postdoctoral Fellow, Argonne NL), Jian Kang (current), James Murray (current) Postdoctoral Advisees (9) A. Singh (Professor, IIT Kanpur, India), S. Theodorakis (Professor, University of Cyprus, Cyprus), J. H. Kim (Professor and Chair of Physics, University of North Dakota), Z. -

1 Johns Hopkins and Slaveholding Preliminary Findings, December 8

Johns Hopkins and Slaveholding Preliminary Findings, December 8, 2020 Hard Histories at Hopkins hardhistory.jhu.edu Martha S. Jones, Director [email protected] Overview Our research began when a colleague brought to the university’s attention an 1850 US census return for Johns Hopkins: A “slave schedule” that attributed the ownership of four enslaved men (aged 50, 45, 25, and 18) to Hopkins. Preliminary research confirmed that the “Johns Hopkins” associated with this census return was the same person for whom the university was later named.1 This evidence ran counter to the long-told story about Johns Hopkins, one that posited him as the son of a man, Samuel Hopkins, who had manumitted the family’s slaves in 1807. Johns Hopkins himself was said to have been an abolitionist and Quaker, the implication being that he opposed slavery and never owned enslaved people.2 The details of the 1850 census slave schedule for Johns Hopkins have generated new research along four lines of inquiry. How had the university for so long told a story about Hopkins that did not account for his having held enslaved people? Which aspects of the Hopkins family story can be confirmed by evidence? What do we learn about Hopkins and his family when we investigate their relationship to slavery anew? And, who were the enslaved people in the Hopkins households and what can we know about their lives? Our observations are preliminary but important. The US census schedules for 1840 and 1850 report that in those years Johns Hopkins owed enslaved people who were part of his Baltimore household (one person in 1840 and four people in 1850.) The evidence also shows that in 1778 Johns Hopkins the elder – grandfather to Johns Hopkins – manumitted enslaved people (with important qualifications detailed below.) Samuel Hopkins – father to Johns Hopkins – dealt in the labor of free Black children and also may have dealt in slaveholding and manumission, but we have recovered no evidence that he manumitted enslaved people. -

Mount Vernon: Baltimore’S Historic LGBT Neighborhood

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 16 January 2016 Exhibition Review: Mount Vernon: Baltimore’s Historic LGBT Neighborhood Amanda Castro CSUSB Blanca Garcia-Barron CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the History of Gender Commons Recommended Citation Castro, Amanda and Garcia-Barron, Blanca (2016) "Exhibition Review: Mount Vernon: Baltimore’s Historic LGBT Neighborhood," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/16 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews Exhibition Review: Mount Vernon: Baltimore’s Historic LGBT Neighborhood By Amanda Castro and Blanca Garcia-Barron Before John Travolta played Edna Turnblad in the 2007 remake of John Waters’ Hairspray (1988), the actress known as Divine played the famous role first. Divine, born Harris Glen Milstead, had been John Waters’ muse for twenty years prior to his most famous and successful film, Hairspray, in 1988. As a filmmaker, Waters has had a reputation for making underground satirical films set in the Baltimore, Maryland area that have often been deemed obscene. In the early 1960s and 1970s, Divine played many of the titular roles in films like Pink Flamingos, Female Trouble, and Polyester. Central themes of the films were fetishes, ennui in suburbia, and Baltimore. Deconstructed, Waters’ films reflected an exaggerated portrayal of the repressive attitudes toward homosexuality and sex in 1950s America. -

Supplemental Digital Appendix 1

Supplemental digital content for Collins ME, Rum S, Wheeler J, Antman K, Brem H, Carrese J, Glennon M, Kahn J, Ohman EM, Jagsi R, Konrath S, Tovino S, Wright S, Sugarman J. Ethical issues and recommendations in grateful patient fundraising and philanthropy. Acad Med. Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 Participants in the Summit on the Ethics of Grateful Patient Fundraising *Indicates summit planning committee member Karen Antman, MD Provost, Boston University Medical Campus Dean, School of Medicine Boston University Boston, Massachusetts Pat Bernstein Patient, Philanthropist Baltimore, Maryland Don Bradfield, JD, MEd Senior Counsel for HIPAA Johns Hopkins Healthcare Institutions Baltimore, Maryland Henry Brem, MD Harvey Cushing Professor of Neurosurgery Director, Department of Neurosurgery Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, Maryland Joseph Carrese, MD, MPH, FACP* Professor of Medicine Core Faculty, Berman Institute of Bioethics Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland Megan Collins, MD, MPH* Assistant Professor of Ophthalmology Wilmer Eye Institute Core Faculty, Berman Institute of Bioethics Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Baltimore, Maryland Copyright © the Association of American Medical Colleges. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited. 1 Supplemental digital content for Collins ME, Rum S, Wheeler J, Antman K, Brem H, Carrese J, Glennon M, Kahn J, Ohman EM, Jagsi R, Konrath S, Tovino S, Wright S, Sugarman J. Ethical issues and recommendations in grateful patient fundraising and philanthropy. Acad Med.