Vincetoxicum Rossicum (Asclepiadaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Release of the Leaf-Feeding Moth, Hypena Opulenta (Christoph)

United States Department of Field release of the leaf-feeding Agriculture moth, Hypena opulenta Marketing and Regulatory (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Programs Noctuidae), for classical Animal and Plant Health Inspection biological control of swallow- Service worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Field release of the leaf-feeding moth, Hypena opulenta (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), for classical biological control of swallow-worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

Alexander Krings Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology North Carolina State University Raleigh, North Carolina 27695-7612, U.S.A

Index of names and types in West Indian Gonolobinae (Apocynace- ae: Asclepiadoideae), including fourteen new lectotypifications, one neotypification, A new name, and A new combination Alexander Krings Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology North Carolina State University Raleigh, North Carolina 27695-7612, U.S.A. [email protected] ABSTRACT Types and their location of deposit are provided for taxa of subtribe Gonolobinae (Apocynaceae: Asclepiadoideae) in the West Indies. The following fourteen taxa are lectotypified: Gonolobus bayatensis Urb., G. broadwayae Schltr., G. ciliatus Schltr., G. dictyopetalus Urb. & Ekman, G. ekmanii Urb., G. nipensis Urb., G. sintenisii Schltr., G. tigrinus Griseb., G. tobagensis Urb., G. variifolius Schltr., Ibatia mollis Griseb., Poicilla costata Urb., Poicilla tamnifolia Griseb., and Poicillopsis crispiflora Urb. Gonolobus grenadensis Schltr. is neotypified. A new name and a new combination in Matelea Aubl. are respectively proposed for Jacaima parvifolia Proctor and J. costata (Urb.) Rendle var. goodfriendii Proctor. RESUMEN Se aportan tipos y su localización de taxa de la subtribu Gonolobinae (Apocynaceae: Asclepiadoideae) en las Indias Occidentales. Se lectotipifican los siguientes catorce taxa: Gonolobus bayatensis Urb., G. broadwayae Schltr., G. ciliatus Schltr., G. dictyopetalus Urb. & Ekman, G. ekmanii Urb., G. nipensis Urb., G. sintenisii Schltr., G. tigrinus Griseb., G. tobagensis Urb., G. variifolius Schltr., Ibatia mollis Griseb., Poicilla costata Urb., Poicilla tamnifolia Griseb., y Poicillopsis crispiflora Urb. Se neotipifica Gonolobus grenadensis Schltr. Se propone un nombre y una combinación nueva en Matelea Aubl. para Jacaima parvifolia Proctor y J. costata (Urb.) Rendle var. goodfriendii Proctor respectivamente. INTRODUCTION Subtribe Gonolobinae (Apocynaceae: Asclepiadoideae) comprises about fifty species in the West Indies, here defined to include the Greater and Lesser Antilles, the Bahamas, Trinidad and Tobago, Aruba and the Neth- erland Antilles, and the Cayman Islands. -

Asclepias Incarnata – Swamp-Milkweed

Cultivation Notes No. 56 THE RHODE ISLAND WILD PLANT SOCIETY Fall 2011 Swamp-milkweed – Asclepias incarnata Family: Asclepiadaceae By M.S. Hempstead The milkweeds, genus Asclepias, are a friendly bunch. They look enough alike to be clearly related to each other, but at least our Rhode Island species’ are different enough to be easily distinguishable from each other. Furthermore, they are big, bold and tall, easy on creaking backs. Eight of the 110 species found in North America appear in the Vascular Flora of Rhode Island, although one of them, A. purpurascens, hasn’t been reported in the state since 1906. A. quadrifolia is listed as “State Endangered,” and four of the others are “Of Concern.” That leaves A. syriaca, Common Milkweed, and A. incarnate, Swamp-milkweed, as abundant. A. syriaca can be found in just about any unmowed field. A. incarnata is common in its favorite wet environment, on the shores of many of our rivers and ponds. Swamp- milkweed, with its bright pink flowers, is no less glamorous than its popular but rarer cousin, Butterfly-weed (A. tuberosa). Both would probably prefer that we not mention their reviled cousin, Black Swallowwort (Vincetoxicum nigrum). The milkweeds’ pollination mechanism is so complex that one wonders how the Swamp-milkweed job ever gets done. In the center of the flower is the gynostegium, a stumplike structure, consisting of the stigmatic head with five stamens fused to the outside of it. Each stamen is hidden behind one of the five petal-like hoods that surround the gymnostegium. The pollen-containing anthers, instead of waving in the breeze as in normal flowers, are stuck to the sides of the gynostegium. -

Establishment of the Invasive Perennial Vincetoxicum Rossicum Across a Disturbance Gradient in New York State, USA

Plant Ecol (2010) 211:65–77 DOI 10.1007/s11258-010-9773-2 Establishment of the invasive perennial Vincetoxicum rossicum across a disturbance gradient in New York State, USA Kristine M. Averill • Antonio DiTommaso • Charles L. Mohler • Lindsey R. Milbrath Received: 23 October 2009 / Accepted: 7 April 2010 / Published online: 22 April 2010 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract Vincetoxicum rossicum (pale swallow- tillage and herbicide-only plots [1.6 ± 0.5%]. Of those wort) is a non-native, perennial, herbaceous vine in seedlings that emerged, overall survival was high at the Apocynaceae. The species’ abundance is steadily both locations (70–84%). Similarly, total (above ? increasing in the northeastern United States and belowground) biomass was greater in herbicide ? till- southeastern Canada. Little is known about Vincetox- age and herbicide-only plots than in mowed and icum species recruitment and growth. Therefore, we control plots at both locations. Thus, V. rossicum was conducted a field experiment in New York State to successful in establishing and surviving across a range address this knowledge gap. We determined the of disturbance regimens particularly relative to other establishment, survival, and growth of V. rossicum old field species, but growth was greater in more during the first 2 years after sowing in two old fields disturbed treatments. The relatively high-establish- subjected to four disturbance regimens. We hypothe- ment rates in old field habitats help explain the sized that establishment and survival would be higher invasiveness of this Vincetoxicum species in the in treatments with greater disturbance. At the better- northeastern U.S. -

Number 11 – July 17, 2017 Honeyvine Milkweed Honeyvine Milkweed (Ampelamus Albi- Dus Or Cynanchum Laeve) Is a Native, Per

Number 11 – July 17, 2017 Honeyvine Milkweed I have always thought of this plant as a weed. Recently I spent some time pull- Honeyvine milkweed (Ampelamus albi- ing new shoots from a bed for about the dus or Cynanchum laeve) is a native, per- third time this summer. It is aggressive ennial vine that spreads by seed and long and persistent and I know it will be spreading roots. The stems are slender, back. Unfortunately, herbicides are not smooth, twining, and without the charac- an option for this particular site. Re- teristic milky sap that is typically present peated hand removal can eventually with other milkweed species. The leaves eliminate it. are dark green, smooth and large, grow- ing up to 6 inches long. They are heart- I have learned, however, that to many shaped on long petioles and opposite on this plant is desirable as it serves as a the stem, which helps to distinguish this food source for the Monarch butterfly. species from similar looking weedy vines Butterfly gardening is quite popular now such as bindweeds. Flowers appear mid- with the decline of the Monarch popula- summer and are long lasting. Flowers tion. I came across one-pint plants are small, whitish or pinkish, sweetly fra- available for sale on eBay. Had I have grant, and borne in clusters – very differ- known this plant was so desirable I ent in appearance than the funnel shaped would have been carefully potting up flowers of bindweed and morningglory those new shoots. Upon telling my hus- vines. The flowers will develop into a 3 to band about my findings and actions, he 6 inch long, smooth, green seed pod that replied with, “and that’s why we’re not is similar to that of common milkweed. -

La Flora Patrimonial De Quito Descubierta Por La Expedición De

AVANCES EN CIENCIAS E INGENIERÍAS ARTÍCULO/ARTICLE SECCIÓN/SECTION B La flora patrimonial de Quito descubierta por la expedición de Humboldt y Bonpland en el año 1802 Carlos Ruales1,∗ Juan E. Guevara2 1Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Colegio de Agricultura, Alimentos y Nutrición. Diego de Robles y Vía Interoceánica, Quito, Ecuador. 2Herbario Alfredo Paredes (QAP), Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Central del Ecuador Apartado Postal 17-01-2177, Quito, Ecuador. ∗Autor principal/Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Editado por/Edited by: D. F. Cisneros-Heredia, M.Sc. Recibido/Received: 04/14/2010. Aceptado/Accepted: 08/25/2010. Publicado en línea/Published on Web: 12/08/2010. Impreso/Printed: 12/08/2010. Abstract The results from this research are based on historical data and data from herbarium co- llections prepared by Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland in 1802 in the city of Quito and its surroundings. In the research, 142 species from the Humboldt and Bonpland’s collections have been selected because of their patrimonial value for the city’s inhabitants; those species were collected for the first time in this area and the plant collections include type-specimens used to describe the species. Twenty-five species are endemic to Ecuador and from those, Cynanchum serpyllifolium (Asclepiadaceae) has not been found for more than 100 years, while Aetheolaena ledifolia (Asteraceae) and Cyperus multifolius (Cypera- ceae) are only known from their type-collections made in 1802. Almost 80 per cent of the collected species were herbs, which showed the advanced human intervention at the time. These premises help to propose a plan that manages patrimonial plant concepts in Quito and its surrounding towns and to increase the appropriation and valorization processes. -

Biota Colombiana • Vol

Biota Colombiana • Vol. 10 - Números 1 y 2, 2009 Volumen especial de la Orinoquia Una publicación del / A publication of: Instituto Alexander von Humboldt En asocio con / In collaboration with: Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia BIOTA COLOMBIANA Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras - Invemar Missouri Botanical Garden ISSN 0124-5376 Volumen 10 • Números 1 y 2, enero - diciembre de 2009 Volumen especial de la Orinoquia TABLA DE CONTENIDO / TABLE OF CONTENTS Flora de la Estrella Fluvial de Inírida (Guainía, Colombia) – D. Cárdenas, N. Castaño & S. Sua . 1 Insectos de la Orinoquia colombiana: evaluación a partir de la Colección Entomológica del Instituto Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH) – I. Morales-C. & C. Medina . .31 Escarabajos coprófagos (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) de la Orinoquia colombiana – C. Medina & L. Pulido . .55 Lista de los moluscos (Gastropoda-Bivalvia) dulceacuícolas y estuarinos de la cuenca del Orinoco (Venezuela) – C. Lasso, R. Martínez-E., J. Capelo, M. Morales-B. & A. Sánchez-M. .63 Lista de los crustáceos decápodos de la cuenca del río Orinoco (Colombia-Venezuela) – G. Pereira, C. Lasso, J. Mora-D., C. Magalhães, M. Morales-B. & M. Campos. .75 Peces de la Estrella Fluvial Inírida: ríos Guaviare, Inírida, Atabapo y Orinoco (Orinoquia colombiana) – C. Lasso, J. Usma, F. Villa, M. Sierra-Q., A. Ortega-L., L. Mesa, M. Patiño, O. Lasso-A., M. Morales-B., K. González-O., M. Quiceno, A. Ferrer & C. Suárez . .89 Lista de los peces del delta del río Orinoco, Venezuela – C. Lasso, P. Sánchez-D., O. Lasso-A., R. Martín, H. Samudio, K. González-O., J. Hernández-A. -

The Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Study of Japanese Asclepiadoideae(Apocynaceae)

The phylogenetic and evolutionary study of Japanese Asclepiadoideae(Apocynaceae) 著者 山城 考 学位授与機関 Tohoku University 学位授与番号 2132 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10097/45710 DoctoralThesis TohokuUniversity ThePhylogeneticandEvolutionaryStudyofJapanese Asclepiadoideae(Apocynaceae) (日 本 産 ガ ガ イ モ 亜 科(キ ョ ウ チ ク トウ科)の 系 統 ・進 化 学 的 研 究) 2003 TadashiYamashiro CONTENTS Abstract 2 4 ChapterI.Generalintroduction 7 ChapterII.TaxonomicalrevisiononsomeIapaneseAsclepiadoideaespecies 2 Q / ChapterIII.ChromosomenumbersofJapaneseAsclepiadoideaespecies 3 0 ChapterIV、PollinationbiologyofIapaneseAsclepiadoideaespecies ChapterV.Acomparativestudyofreproductivecharacteristicsandgeneticdiversitiesonan autogamousderivativeT・matsumuraeanditsprogenitorT・tanahae 56 ChapterVI.Molecularphylogenyofレfη`etoxicumanditsalliedgenera 75 ChapterVII.EvolutionarytrendsofIapaneseVincetoxi`um 96 Ac㎞owledgement 100 References 101 1 ABSTRACT ThesubfamilyAsclepiadoideae(Apocynaceae)comprisesapproximately2,000species, andmainlyoccurstropicalandsubtropicalregionsthroughtheworld.lnJapan,35species belongingtoninegenerahavebeenrecorded.Altholユghmanytaxonomicstudieshavebeen conductedsofar,thestudiestreatingecologicalandphylogeneticalaspectsarequitefew. Therefore,Ifirs走conductedtaxonomicre-examinationforIapaneseAsclepiadoideaebasedon themorphologicalobservationofherbariumspecimensandlivingPlants.Furthermore cytotaxonomicstudy,pollinatorobserva且ons,breedingsystemanalysisofanautogamous species,andmolecUlarphylogeneticanalysisonVincetoxicumanditsalliedgenerawere performed.Then,IdiscussedevolutionarytrendsandhistoriesforVincetoxicumandits -

Enemy of My Enemy: Can the Rhizosphere Biota of Vincetoxicum Rossicum Act As Its “Ally” During Invasion?

Enemy of my Enemy: Can the Rhizosphere Biota of Vincetoxicum rossicum Act as its “Ally” During Invasion? by Angela Dukes A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Biology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Angela Dukes, November 2017 ABSTRACT Enemy of my Enemy: Can the Rhizosphere Biota of Vincetoxicum rossicum Act as its “Ally” During Invasion? Angela Dukes Advisors: Dr. Pedro Antunes University of Guelph, 2017 Dr. Kari Dunfield The ‘Enemy of my enemy’ (EE) is a major hypothesis in invasion ecology. It states that a non-native invader ‘accumulates generalist pathogens, which limit competition from indigenous competitors’. Few empirical studies have tested the EE hypothesis in plant invasions, especially on biotic rhizosphere interactions. Here, the EE hypothesis was tested by applying rhizosphere biota from the invasive plant Vincetoxicum rossicum (VIRO) to five co-occurring native plant species, and four native legume species, respectively. Each of the native plant species, and VIRO were grown under controlled conditions for three months, either in presence or absence of soil biota from VIRO invaded and non-invaded soils. Rhizosphere biota from invaded areas had variable effects among native plants (including legumes). It was concluded that the accumulation of rhizosphere enemies that ‘spill’ onto native plants may not be a major factor in the invasive success of VIRO. The EE hypothesis was not supported. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I deeply appreciated the patience of my supervisors: Dr. Kari Dunfield and Dr. Pedro Antunes. I worked in the Plant and Soil Ecology Lab at Algoma University with Dr. -

Black and Pale Swallow-Wort (Vincetoxicum Nigrum and V

Chapter 13 Black and Pale Swallow-Wort (Vincetoxicum nigrum and V. rossicum): The Biology and Ecology of Two Perennial, Exotic and Invasive Vines C.H. Douglass, L.A. Weston, and A. DiTommaso Abstract Black and pale swallow-worts are invasive perennial vines that were introduced 100 years ago into North America. Their invasion has been centralized in New York State, with neighboring regions of southern Canada and New England also affected. The two species have typically been more problematic in natural areas, but are increasingly impacting agronomic systems such as horticultural nurs- eries, perennial field crops, and pasturelands. While much of the literature reviewed herein is focused on the biology and management of the swallow-worts, conclu- sions are also presented from research assessing the ecological interactions that occur within communities invaded by the swallow-wort species. In particular, we posit that the role of allelopathy and the relationship between genetic diversity lev- els and environmental characteristics could be significant in explaining the aggres- sive nature of swallow-wort invasion in New York. Findings from the literature suggest that the alteration of community-level interactions by invasive species, in this case the swallow-worts, could play a significant role in the invasion process. Keywords Allelopathy • Genetic diversity • Invasive plants • Swallow-wort spp. • Vincetoxicum spp. Abbreviations AMF: Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi; BSW: Black swallow-wort; PSW: Pale swallow-wort C.H. Douglass () Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA [email protected] A. DiTommaso Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853, USA L. -

Milkweed and Monarchs

OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WILDLIFE MILKWEEDS AND MONARCHS Acknowledgments Table of Contents We thank Dr. David Horn, past president of the Ohio Lepidopterists, 03 MONARCH LIFE CYCLE for his thoughtful review of this publication. Our appreciation goes 04 MONARCH MIGRATION to the Ohio Lepidopterists, and Monarch Watch. These organizations work tirelessly to promote the conservation of butterflies and moths. 05 PROBLEMS & DECLINE COVER PHOTO BY KELLY NELSON 06 MILKWEEDS 07 OTHER MILKWEED SPECIALISTS 08 MONARCH NURSERY GARDEN Introduction 09 FIVE EXCELLENT MILKWEEDS Text and photos by Jim McCormac, Ohio Division of Wildlife, unless otherwise stated. 10 SUPERB MONARCH NECTAR SOURCES The Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is one of North Amer- ica’s most iconic insects. The gorgeous golden-brown and black but- terfly is probably the most celebrated insect on the continent, and the migration of the eastern population is conspicuous and spectacular. Southbound Monarchs can appear anywhere, even in highly urban- ized locales, and the butterflies often use backyard gardens as way sta- tions. Occasionally a resting swarm of hundreds or even thousands of butterflies is encountered. The spectacle of trees dripping with living leaves of butterflies is unlikely to be forgotten. PHOTO BY CHRIS FROST A Pictorial Journey From Caterpillar to Chrysalis to Butterfly PHOTOS BY STEVEN RUSSEL SMITH Monarch Butterfly Life Cycle Like all species in the order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), soon hatch. The caterpillars begin eating the milkweed foliage, and Monarchs engage in complete metamorphosis. This term indicates grow rapidly. The growth process involves five molts where the cater- that there are four parts to the life cycle: egg, caterpillar, pupa, and pillar sheds its skin and emerges as a larger animal. -

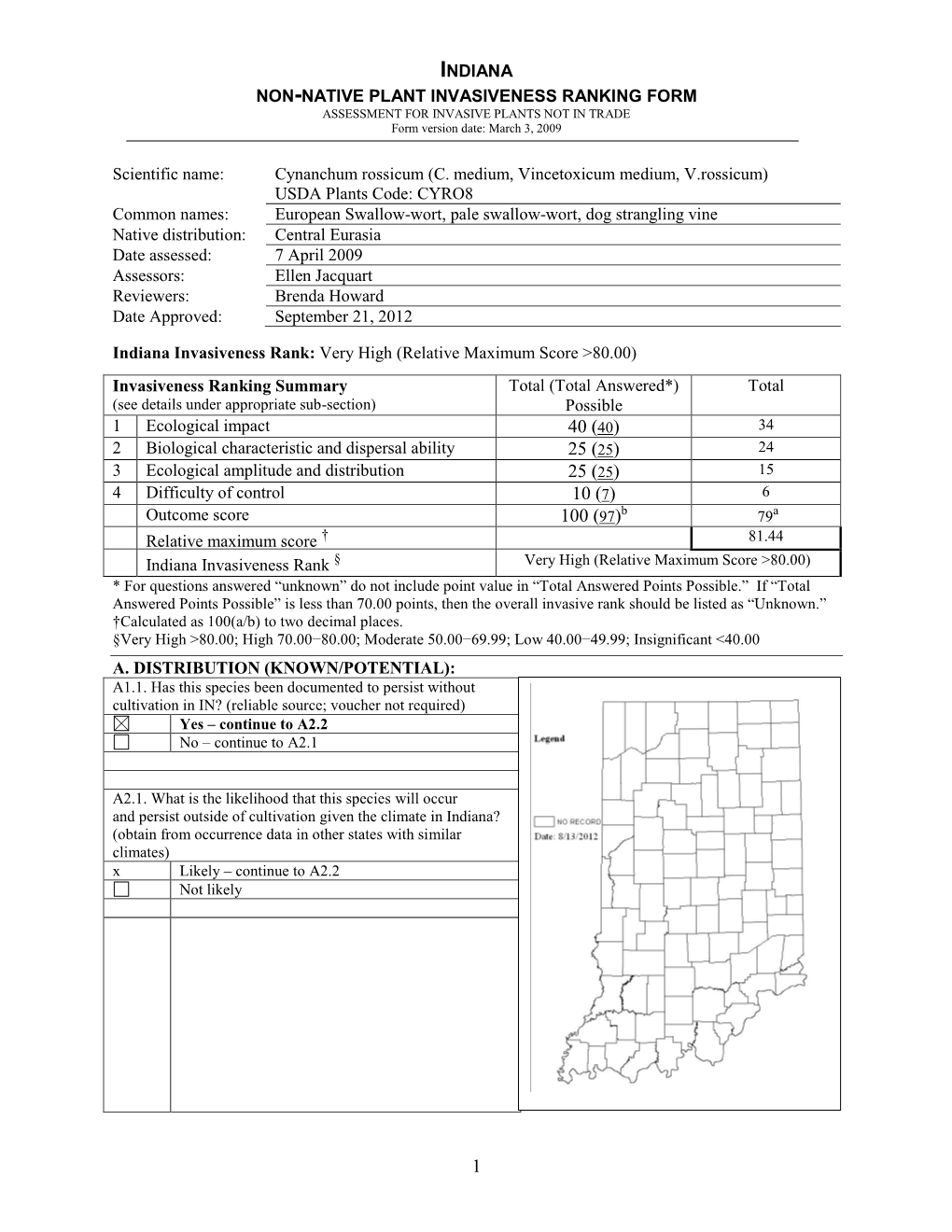

Invasive Dog-Strangling Vine (Cynanchum Rossicum)

Invasive Dog-strangling Vine (Cynanchum rossicum) Best Management Practices in Ontario DRAFT ontario.ca/invasivespecies Foreword These Best Management Practices (BMPs) are designed to provide guidance for managing invasive Dog- strangling Vine (Cynanchum rossicum [= Vincetoxicum rossicum]) in Ontario. Funding and leadership in the development of this document was provided by the Canada/Ontario Invasive Species Centre. They were developed by the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (OIPC), its partners and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). These guidelines were created to complement the invasive plant control initiatives of organizations and individuals concerned with the protection of biodiversity, agricultural lands, crops and natural lands. These BMPs are based on the most effective and environmentally safe control practices known from research and experience. They reflect current provincial and federal legislation regarding pesticide usage, habitat disturbance and species at risk protection. These BMPs are subject to change as legislation is updated or new research findings emerge. They are not intended to provide legal advice, and interested parties are advised to refer to the applicable legislation to address specific circumstances. Check the website of the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (www.ontarioinvasiveplants.ca) or Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (www.ontario.ca/invasivespecies) for updates. Anderson, Hayley. 2012. Invasive Dog-strangling Vine (Cynanchum rossicum) Best Management Practices in Ontario. Ontario