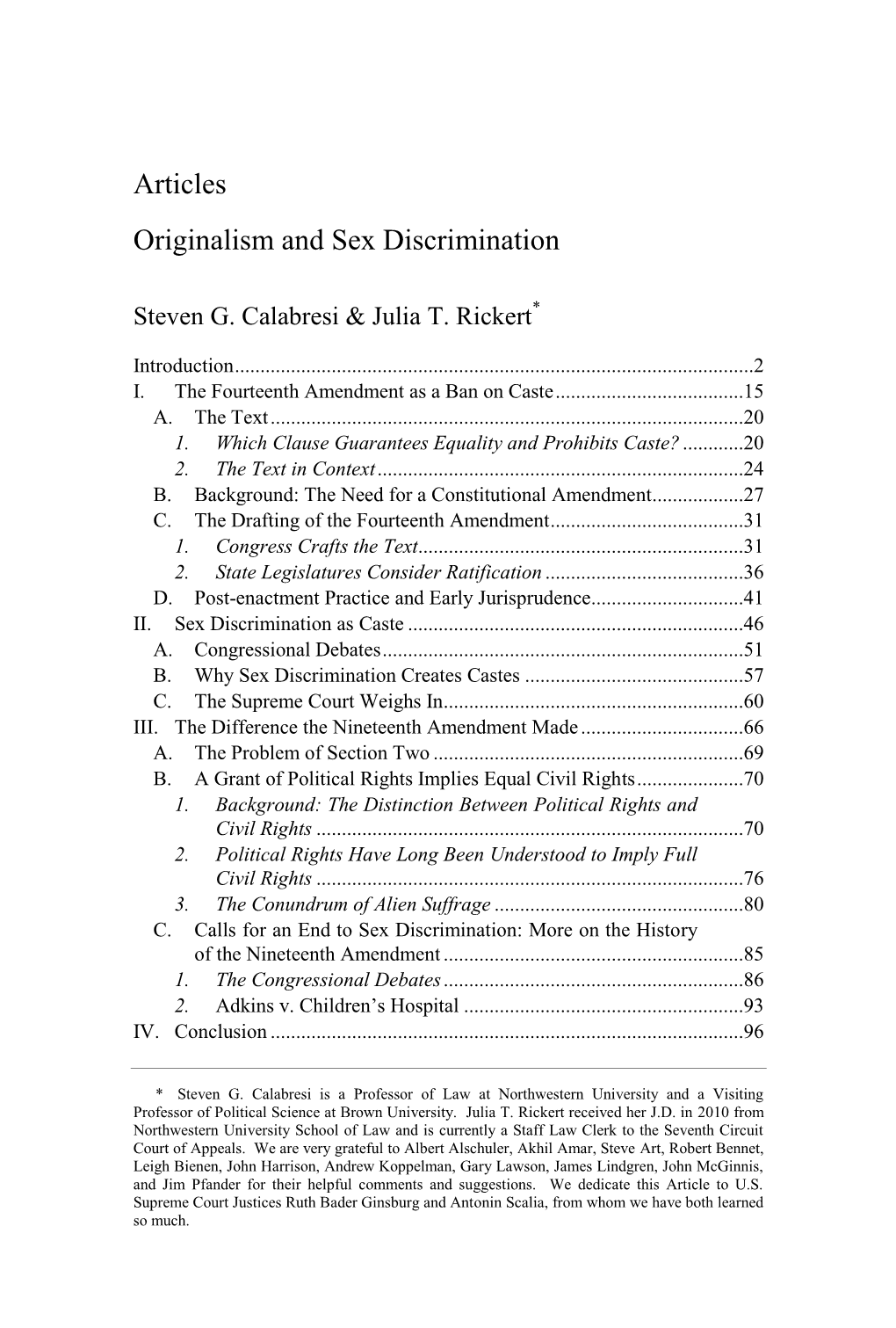

Articles Originalism and Sex Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Late Justice Scalia Was Wrong: the Fallacies of Constitutional Textualism

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2017 Why the Late Justice Scalia Was Wrong: The Fallacies of Constitutional Textualism Ken Levy Louisiana State University Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Repository Citation Levy, Ken, "Why the Late Justice Scalia Was Wrong: The Fallacies of Constitutional Textualism" (2017). Journal Articles. 413. https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship/413 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Ken Levy, Why the Late Justice Scalia Was Wrong: The Fallacies of Constitutional Textualism, 21 Lewis & Clark L. Rev. 45 (2017) Provided by: LSU Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Fri Mar 16 15:53:01 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device WHY THE LATE JUSTICE SCALIA WAS WRONG: THE FALLACIES OF CONSTITUTIONAL TEXTUALISM by Ken Levy * The late justice Scalia emphatically rejected the notion that there is a general "right to privacy" in the Constitution, despite the many cases that have held otherwise over the past several decades. -

The Alchemy of Dissent

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2010 The Alchemy of Dissent Jamal Greene Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jamal Greene, The Alchemy of Dissent, 45 TULSA L. REV. 703 (2010). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/942 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ALCHEMY OF DISSENT Jamal Greene* Stephen M. Feldman, Free Expression and Democracy in America: A History (U. Chi. Press 2008). Pp. 544. $55.00. On July 10, 2010, the Orange/Sullivan County NY 912 Tea Party organized a "Freedom from Tyranny" rally in the sleepy exurb of Middletown, New York. Via the group's online Meetup page, anyone who was "sick of the madness in Washington" and prepared to "[d]efend our freedom from Tyranny" was asked to gather on the grass next to the local Perkins restaurant and Super 8 motel for the afternoon rally.1 Protesters were encouraged to bring their lawn chairs for the picnic and fireworks to follow. There was a time when I would have found an afternoon picnic a surprising response to "Tyranny," but I have since come to expect it. The Tea Party movement that has grown so exponentially in recent years is shrouded in irony. -

Justice Scalia's Bottom-Up Approach to Shaping The

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 25 (2016-2017) Issue 1 Article 7 October 2016 Justice Scalia’s Bottom-Up Approach to Shaping the Law Meghan J. Ryan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Courts Commons, Legal Biography Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Repository Citation Meghan J. Ryan, Justice Scalia’s Bottom-Up Approach to Shaping the Law, 25 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 297 (2016), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol25/iss1/7 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj JUSTICE SCALIA’S BOTTOM-UP APPROACH TO SHAPING THE LAW Meghan J. Ryan * ABSTRACT Justice Antonin Scalia is among the most famous Supreme Court Justices in history. He is known for his originalism and conservative positions, as well as his witty and acerbic legal opinions. One of the reasons Justice Scalia’s opinions are so memorable is his effective use of rhetorical devices, which convey colorful images and understandable ideas. One might expect that such powerful opinions would be effective in shaping the law, but Justice Scalia’s judicial philosophy was often too conservative to persuade a majority of his fellow Justices on the Supreme Court. Fur- ther, his regular criticisms of his Supreme Court colleagues were not conducive to building majority support for his reasoning. Hoping to still have a lasting impact on the law, Justice Scalia seemed to direct his rhetoric at a different audience. -

The Nomination of Amy Coney Barrett

The Nomination of Amy Coney Barrett What’s at Stake? The Separation of Church and State A report from Americans United for Separation of Church and State September 26, 2020 INTRODUCTION Our country was founded on the principle of religious freedom—a tradition and ideal that remains central to who we are today. The separation of church and state is the linchpin of religious freedom and one of the hallmarks of American democracy. It ensures that every American is able to practice their religion or no religion at all, without government interference, as long as they do not harm others. It also means that our government officials, including our judges, can’t favor or disfavor religion or impose their personal religious beliefs on the law. Separation safeguards both religion and government by ensuring that one institution does not control the other, allowing religious diversity in America to flourish. Our Supreme Court must respect this fundamental principle. The American people agree: According to a poll conducted in July of 2019 by Anzalone Liszt Grove Research on behalf of Americans United, 60 percent of likely voters say protecting the separation of religion and government is either one of the most important issues to them personally or very important. Justice Ginsburg was a staunch supporter of the separation of church and state. Yet President Trump has nominated Amy Coney Barrett, whose record indicates hostility toward church-state separation, to fill her seat. Religious freedom for all Americans hangs in the balance with this nomination. AT STAKE: Whether Religious Exemptions Will Be Used to Harm Others, Undermine Nondiscrimination Laws, and Deny Access to Healthcare Religious freedom is a shield that protects religion, not a sword to harm others or to discriminate. -

How Star Wars Illuminates Constitutional Law

HOW STAR WARS ILLUMINATES CONSTITUTIONAL LAW † CASS R. SUNSTEIN ABSTRACT: Human beings often see coherence and planned design when neither exists. This is so in movies, literature, history, economics, and psychoanalysis – and constitutional law. Contrary to the repeated claims of George Lucas, its principal author, the Star Wars series was hardly planned in advance; it involved a great deal of improvisation and surprise, even to Lucas himself. Serendipity and happenstance, sometimes in the forms of eruptions of new thinking, play a pervasive and overlooked role in the creative imagination, certainly in single authored works, and even more in multi-authored ones extending over time. Serendipity imposes serious demands on the search for coherence in art, literature, history, and law. That search leads many people (including Lucas) to misdescribe the nature of their own creativity and authorship. The misdescription appears to respond to a serious human need for sense-making and pattern-finding, but it is a significant obstacle to understanding and critical reflection. Whether Jedi or Sith, many authors of constitutional law are a lot like the author of Star Wars, disguising the essential nature of their own creative processes. KEYWORDS: Serendipity; Judicial Interpretation; Supreme Court; Chain Novel; Originalism. RESUMO: Os seres humanos frequentemente identificam coerência e planejamento quando nenhum desses elementos sequer existe. Tal situação ocorre nos filmes, na Literatura, na História, na Economia e na † Robert Walmsley University Professor, Harvard University. For valuable comments, I am grateful to Tyler Cowen, Elizabeth Emens, George Loewenstein, Martha Nussbaum, Eric Posner, Mark Tushnet, Adrian Vermeule, and Duncan Watts. This essay draws heavily on an earlier and less academic essay, originally published in The New Rambler (2015). -

Originalist Or Original: the Difficulties of Reconciling Citizens United with Corporate Law History Leo E

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 91 | Issue 3 Article 1 4-2016 Originalist or Original: The Difficulties of Reconciling Citizens United with Corporate Law History Leo E. Strine Jr. Delaware Supreme Court Nicholas Walter Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation 91 Notre Dame L. Rev. 877 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\91-3\NDL301.txt unknown Seq: 1 4-APR-16 13:24 ARTICLES ORIGINALIST OR ORIGINAL: THE DIFFICULTIES OF RECONCILING CITIZENS UNITED WITH CORPORATE LAW HISTORY Leo E. Strine, Jr.* & Nicholas Walter** INTRODUCTION Much has and will continue to be written about the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v. FEC.1 In that decision, the Court held that the part of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (the © 2016 Leo E. Strine, Jr. & Nicholas Walter. Individuals and nonprofit institutions may reproduce and distribute copies of this Article in any format at or below cost, for educational purposes, so long as each copy identifies the author, provides a citation to the Notre Dame Law Review, and includes this provision in the copyright notice. * Chief Justice, Delaware Supreme Court; Adjunct Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School; Austin Wakeman Scott Lecturer, Harvard Law School; Senior Fellow, Harvard Program on Corporate Governance; Adjunct Professor, Vanderbilt University School of Law; Henry Crown Fellow, Aspen Institute. -

Importance of Statutory Interpretation Statutory Interpretation Is An

Importance of statutory interpretation Statutory interpretation is an important aspect of the common law. In about half of all reported cases in Australia, the courts are required to rule on the meaning of legislation. Interpretation Acts The meaning of Commonwealth legislation is governed by the provisions in the Acts Interpretations Act (1901). It prescribes the meanings of common terms and provides courts with clear directions to resolve a range of potential inconsistencies. The Traditional (General) Rules – sometimes referred to as Literalism The traditional common-law approach to statutory interpretation was to "look at the words of the Act". This approach was founded on the assumption that the statute alone was a reliable guide to the intent of the Parliament. That is, Parliament said what it means, and means what it said (within the context of the legislation). However, to assist the courts in interpreting legislation, judges relied upon three general rules (REFER SEPARATE DOCUMENT CONCERNING A 4TH RULE – THE MORE THAN RULE). These were the: Literal Rule: The literal rule dictated that the courts gave effect to the "ordinary and natural meaning" of legislation. This Rule was defined by Higgins J, in The Amalgamated Society of Engineers v The Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd (1920). Justice Higgins said “The fundamental rule of interpretation, to which all others are subordinate, is that a statute is to be expounded according to the intent of the Parliament that made it; and that intention has to be found by an examination of the language used in the whole of the statute as a whole. The question is, what does the language mean; and when we find what the language means in it's ordinary and natural sense, it is our duty to obey that meaning, even if we think the result to be inconvenient, impolitic or improbable”. -

WHAT's the POINT of ORIGINALISM? As of Late, a Remarkable Array of Constitutional Theorists Have Declared Themselves Originali

WHAT’S THE POINT OF ORIGINALISM? DONALD L. DRAKEMAN* I. EMBRACING ORIGINALISM As of late, a remarkable array of constitutional theorists have declared themselves originalists of one sort or another,1 and no one is quite sure why.2 Or, perhaps more accurately, everyone is sure, but they all disagree with each other. For some, the originalism command springs directly from the text itself: it is a written Constitution, and the original meaning of the text itself is the law of the land;3 for others, such as Justice Scalia, it is the best (and perhaps only) way to restrain judges from reading * Ph.D., Princeton University, 1988; J.D., Columbia Law School, 1979; A.B., Dartmouth College, 1975. Visiting Fellow, Program on Church, State & Society, Notre Dame Law School; and Fellow in Health Management, University of Cam- bridge. I would like to thank Joel Alicea, David Campbell, Marc DeGirolami, Richard Ekins, Matthew Franck, Mark Movsesian, Phillip Muñoz, Keith Whitting- ton, Brad Wilson, the fellows of the James Madison Program in American Ideas and Institutions at Princeton University, and the Notre Dame Law School Faculty Colloquium for very helpful comments, and Michael Breidenbach for excellent research assistance. The usual disclaimer applies. 1. See generally Thomas B. Colby & Peter J. Smith, Living Originalism, 59 DUKE L.J. 239 (2009); see also Jeffrey Shulman, The Siren Song of History: Originalism and the Religion Clauses, 27 J.L. & RELIGION 163 (2011) (book review). For a discussion of modern originalism, see Joel Alicea, Forty Years of Originalism, 173 POL’Y REV. 69 (2012) and JACK M. -

Statutory Interpretation in a Nutshell

THE CANADIAN BAR REVIEW VOL. XVI - JANUARY, 1938 - - NO. 1 STATUTE INTERPRETATION IN A NUTSHELL PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS RULE I.-If you are trying to guess what meaning a; court will :attach to a section in a statute which has not yet been passed on by a court, you should be careful how you use. Craies' Statute Law and Maxwell on The Interpretation of Statutes. As armouries of arguments for counsel they can be very useful: but, you must know how to choose your weapon. In at least three respects these legal classics are very defective (a) Both books assume one great sun of a principle, "the plain meaning rule", around which revolve .in planetary order a series of minor rules of- construction : both assume that what courts do is unswervingly determined by that one principle . This is not so. Examine a few recent cases and you will find not a principle - nothing so definite as that - but an approach, - a certain attitude towards the words of a statute. Rook closer and -,you will see that there is not one single approach, but three,._ (i) "the literal rule", (ii) "the golden rule", - (iii) "tithe mischièlf rule". Any one of these approaches may be selected by your -.court : which it does decide to "select may, in a élose Yourcase, be t-he determining element in its decision .2 guess should therefore be based on an application of all three approaches : you should not be misled by Craies and Maxwell into thinking there is only one to consider. (b) Both books base their rules not on decisions, not on what the courts did in cases before them, but on dicta, the 1 Thus in Vacher v. -

But That Is Absurd!: Why Specific Absurdity Undermines Textualism Linda D

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Brooklyn Law School: BrooklynWorks Brooklyn Law Review Volume 76 Issue 3 SYMPOSIUM: Article 2 Statutory Interpretation: How Much Work Does Language Do? 2011 But That Is Absurd!: Why Specific Absurdity Undermines Textualism Linda D. Jellum Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Linda D. Jellum, But That Is Absurd!: Why Specific bA surdity Undermines Textualism, 76 Brook. L. Rev. (2011). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol76/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. But That Is Absurd! WHY SPECIFIC ABSURDITY UNDERMINES TEXTUALISM* Linda D. Jellum† INTRODUCTION With 2010 being the twenty-fifth year since Justice Scalia joined the Supreme Court and revived textualism,1 I could not resist exploring and critiquing the absurdity doctrine,2 a doctrine used by Justice Scalia and other * © 2011 Linda D. Jellum. All rights reserved. † Associate Professor of Law, Mercer University School of Law. I would like to thank Lawrence Solan, Rebecca Kysar, and the Brooklyn Law Review for inviting me to contribute to this symposium. I would also like to thank Shelia Scheuerman, Charleston Law School, and the participants in Southeastern Law Scholars Conference for offering me an opportunity to present this article while it was still a work in progress. Finally, David Ritchie and Suzianne Painter-Thorne provided valuable suggestions. -

Originalism: Lessons from Things That Go Without Saying Robert William Bennett Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected]

Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Working Papers 2008 Originalism: Lessons From Things That Go Without Saying Robert William Bennett Northwestern University School of Law, [email protected] Repository Citation Bennett, Robert William, "Originalism: Lessons From Things That Go Without Saying" (2008). Faculty Working Papers. Paper 169. http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/facultyworkingpapers/169 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. NATHANIEL L. NATHANSON MEMORIAL LECTURE UNIVERSITY OF SAN DIEGO LAW SCHOOL March 11, 2008 ORIGINALISM: LESSONS FROM THINGS THAT GO WITHOUT SAYING By Robert W. Bennett1 It is a very special honor to present these Nathanson lectures, and not simply for the obvious reason that I was asked to join a very distinguished list of Nathanson lecturers. I also have fond recollections of an earlier visit to the school–now more than twenty-five years ago, and I am an admirer of the work of several members of the San Diego faculty that intersects in various ways with my own. But most of all Nat Nathanson, after whom the lectures are named, was a dear friend and colleague at Northwestern–and also a hero of mine–for many years. The colleague relationship spanned twenty-four years, and the friendship came easily, and continues with Leah Nathanson who is well-known to you folks in San Diego, and who is here with us today. -

The Second Amendment and “The People”: Who Has the Right to Bear Arms?

The John Marshall Law Review Volume 51 | Issue 1 Article 8 2017 The econdS Amendment and “The eopleP ”: Who Has the Right to Bear Arms?, 51 J. Marshall L. Rev. 199 (2017) Kasim Carbide Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.jmls.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kasim Carbide, The eS cond Amendment and “The eP ople”: Who Has the Right to Bear Arms?, 51 J. Marshall L. Rev. 199 (2017) https://repository.jmls.edu/lawreview/vol51/iss1/8 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by The oJ hn Marshall Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oJ hn Marshall Law Review by an authorized administrator of The oJ hn Marshall Institutional Repository. THE SECOND AMENDMENT AND “THE PEOPLE”: WHO HAS THE RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS? KASIM CARBIDE I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................ 199 A. The Current Problem .............................................. 199 B. Brief Overview ......................................................... 202 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................. 203 A. Incorporation ........................................................... 203 B. Originalism v. Nonoriginalism ............................... 204 C. History of Second Amendment Jurisprudence ...... 205 III. ANALYSIS ......................................................................... 210 A. The Supreme Court’s Reasoning ............................ 210 B. The Seventh Circuit’s Reasoning ..........................