Sacred Music Volume 133, Number 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening of the Year of the Eucharist – June 22-23, 2019

Opening of the Year of the Eucharist – June 22-23, 2019 This Novena prayed nine days before the June 23rd start would be a great way to make immediate preparation for the Year of the Eucharist. The novena would begin on June 14. The link is here: http://www.ewtn.com/Devotionals/novena/Corpus_Christi.htm In the Masses you celebrate on June 22-23, we would suggest the following rituals to open the Year of Eucharist. 1. Gather the faithful outside the main door of the church, weather permitting. * a. Give a brief explanation of the Year of the Eucharist. Share with the faithful that this moment of processing is a symbolic way of entering the Year of the Eucharist. (sample of an explanation is attached) b. Read the decree (attached) c. Process in with a Eucharistic Hymn of your choosing from the resources you have available. d. Carry in the Year of the Eucharist banner. After the processional, have the banner carrier hang the banner on the main door of the parish church. Hooks are provided with the banner and should be attached to the door ahead of time. Additional banners can be ordered. Contact Dionne Eastmo in the Faith Formation Office. 2. Have the parishioners pray the sequence for the Feast of Corpus Christi. You could also sing it although there is no familiar melody available. (The text of the sequence is attached.) 3. Preach about the Year of the Eucharist focusing on the bishop’s desire to deepen and strengthen the faithful’s encounter with the Lord in the celebration of the Mass. -

1 LET US PRAY – REFLECTIONS on the EUCHARIST Fr. Roger G. O'brien, Senior Priest, Archdiocese of Seattle

1 LET US PRAY – REFLECTIONS ON THE EUCHARIST Fr. Roger G. O’Brien, Senior Priest, Archdiocese of Seattle During this Year of the Eucharist, I offer a series of articles on Eucharistic Spirituality: Source of Life and Mission of our Church. Article #1, How We Name Eucharist. Let me make two initial remarks: one on how, in our long tradition, we have named the eucharist, and the other on eucharistic spirituality. We’ve given the eucharist a variety of names, in our church’s practice and tradition. The New Testament called it the Lord’s Supper (Paul so names it in 1 Cor. 11:20); and also the Breaking of the Bread (by Luke, in Acts 2:42,46). Later, a Greek designation was given it, Anamnesis, meaning “remembrance”. It is the remembrance, the memorial of the Lord, in which we actually participate in his dying and rising. Sometimes, it was called simply Communion, underscoring the unity we have with Jesus and one another when we eat the bread and drink the cup (1 Cor. 10:16). We speak of “doing eucharist” together because, in doing it, we have communion with the Lord and one another. Anglicans still use this name, today, to refer to the Lord’s Supper. We call it Eucharist – meaning “thanksgiving” (from the Greek, eucharistein, “to give thanks”). Jesus gave thanks at the Last Supper. And we do so. When we come together to be nourished in word and sacrament, we give thanks for Jesus’ dying and rising. It was also called Sacrifice. Early christian writers spoke of Jesus’ Sacrifice (also calling it his Offering), which was not only a gift received but also the gift whereby we approach God. -

July 12, 2020 Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time

July 12, 2020 Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time The Current Mass Schedule Beginning July 18/19 Temporarily by Sign-Up/Walk-In: -Saturday: 5 PM - St. Philip -Sunday: 9 AM - St. Philip -Sunday: 10:30 AM - St. Mary -Sunday: 12 Noon In Spanish At St. Philip -The Parish Office is open by appointment. -Please call or email us: 360-225-8308 www.stphilipwoodland.com -Please continue to check our website for updates And to Register for Mass. -All meetings and events are cancelled. GOSPEL Matthew 13:1-23 A sower went out to sow. -Sacraments are available Upon request. On that day, Jesus went out of the house and sat down by the sea. Call 360-225-8308 x 9 Such large crowds gathered around him that he got into a boat and sat down, and the whole crowd stood along the shore. -Pastoral Emergencies: Call 360-225-8308 x 9 And he spoke to them at length in parables, saying: “A sower went out to sow. And as he sowed, some seed fell on the path, St. Philip Conference and birds came and ate it up. Some fell on rocky ground, where it had little St. Vincent de Paul soil. It sprang up at once because the soil was not deep, and when the sun PO Box 1150 rose it was scorched, and it withered for lack of roots. Woodland WA 98674 Helpline: 360-841-8734 Some seed fell among thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked it. But some seed fell on rich soil and produced fruit, a hundred or sixty or SUPPORT OUR thirtyfold. -

The Cathedral of Saint Paul Birmingham, Alabama

THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA THE MOST HOLY BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST JUNE 7, 2015 Welcome to the Cathedral of Saint Paul. The order of Mass can be found on page 3 in the Sunday’s Word booklets found in the pew racks or on the pew cards. Please follow this order of worship for today’s music. PRELUDE PRELUDE AND VARIATIONS ON “ADORO TE DEVOTE” GERALD NEAR ENTRANCE HYMN AT THAT FIRST EUCHARIST UNDE ET MEMORES ENTRANCE ANTIPHON (8:30 & 11:00AM) Cibavit eos PSALM 81:17 He fed them with the finest wheat and satisfied them with honey from the rock. KYRIE (5:00PM & 11:00AM) MASS VIII KYRIE (8:30AM) MASS Á 4 (BYRD) GLORIA MASS VIII THE LITURGY OF THE WORD The Mass readings can be found on page 105 of Sunday’s Word. FIRST READING EXODUS 24:3-8 RESPONSORIAL PSALM PSALM 116:12-13, 15-16, 17-18 Music: John Schiavone, © OCP Publications, Inc. SECOND READING HEBREWS 9:11-15 SEQUENCE (8:30 & 11:00AM) LAUDA SION Please join in singing the bolded verses of the sequence along with the cantor. ALLELUIA I am the living bread that came down from heaven, says the Lord; whoever eats this bread will live forever. GOSPEL MARK 14:12-16, 22-26 LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST Page 7 in Sunday’s Word OFFERTORY O FOOD OF EXILES LOWLY INNSBRUCK OFFERTORY MOTET (8:30AM) O SACRUM CONVIVIUM GIOVANNI CROCE O sacrum convivium! in quo Christus sumitur: recolitur memoria passionis eius: mens impletur gratia: et futurae gloriae nobis pignus datur. -

Saints Alive

Welcome to Saints Alive For centuries the faith of our brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers has been fashioned, refined, colored and intensified by the sheer variety and passion of the lives of the great Christian saints. Their passions, their strengths and weaknesses, the immense variety of their lives have intrigued children young and old for ages. You may even have been named for a particular saint – Dorothy, Dolores, Anne or Elizabeth; Malachi, Francis or even Hugh. So why not celebrate some of those remarkable people through music? As we resume our trek along the Mission Road, we high- light music written in the Americas to celebrate the life and work of our city’s patron saint, Francis, as well as the lives and mission of other men and women venerated by the great musical masters. Saint Cecilia, patroness of music, is very much alive and present in a setting of “Resuenen los cla- rines” by the Mexican Sumaya. Bassani, an Italian who thrived in Bolivia when it was still called Upper Peru, pays homage to Saint Joseph in a Mass setting bearing his name. Its blend of self-taught craftsmanship and mastery of orchestration is fascinating, intriguing, even jolly. It’s as if Handel and the young Mozart had joined hands, jumped on a boat and headed to the heart of South America. What a nice addition to our library! Chants taught by the zealous, mission-founding Sancho have been sent our way – chants in his own hand, no less. Ignatius Loyola is represented by three short motets (that’s almost too glamorous a name for them, they are more folkish in their style) from Bolivia. -

Ideas for Celebrating the Year of the Eucharist at Divine Mercy Parish

1 of 3 Ideas for Celebrating the Year of the Eucharist at Divine Mercy Parish Put more Eucharist-centered CDs and books on the Lighthouse cart Periodically (monthly) place appropriate Prayers Before the Blessed Sacrament in the bulletin Introduce to the congregation and sing more Eucharist-centered songs at Mass Before the beginning of the Year of the Eucharist, publicize the year and give a taste of upcoming parish activities. Monthly activities which will help to focus our parishioners on the Eucharist: o December ♣ emphasize time before the Blessed Sacrament as especially appropriate during Advent ♣ give out 13 Powerful Ways to Pray to congregation ♣ Fair Trade Sale – Eucharist commits us to serving the poor o January ♣ Catholic Schools Week focus on the Eucharist Class tours of the church Class visits to the Blessed Sacrament Chapel for prayer 2 of 3 o February ♣ Parish Mission with Sarah Hart with special emphasis on Eucharist o March ♣ Meal Packing (CRS event) – Eucharist commits us to the poor ♣ Taize’ Prayer with Adoration o April ♣ Divine Mercy Chaplet (Eucharistic themed) - 4/8/18 o May ♣ Rosary Triduum with Adoration o June ♣ Corpus Christi Procession before Masses – 5/3/18 o July ♣ Promote Monday morning and First Friday Adoration o August ♣ Promote Monday morning and First Friday Adoration o September ♣ Religious Education and Alpha Course begin – both focused on Evangelization and bringing adults and children to the Eucharist 3 of 3 o October ♣ Celebration of Stewardship Month in the parish with various events each weekend ♣ Collection of needed items for local families in need ♣ Rosary Triduum with Adoration o November ♣ Senior Thanksgiving Luncheon . -

Sacristan Temporary Procedures All Saints Lansing May 18, 2018

Sacristan Temporary Procedures All Saints Lansing May 18, 2018 Dear Sacristans, Thank you so much for all you do! As you know there have been some changes recently and there will be a few more as we strive to serve our Eucharistic Lord in the best way possible and renew our procedures in the context of the Diocesan Year of the Eucharist. As you enter the Sacristy the next time you will notice that some things have been reorganized. There are labels on the doors of the cupboards that indicate where everything is. The counter is to remain empty and clean. Order and cleanliness will help us make our sacristy a space of hospitality. This short message is meant to help you navigate this time of transition. As we renew procedures for other liturgical ministers over the next couple weeks we will consolidate an updated handbook for all N.E.T. Catholic liturgical ministers to be promulgated at our celebration of the closing of the Year of the Eucharist on June 5th with Solemn Exposition and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament to be held at Holy Cross at 7 pm for all of our three parishes. All liturgical ministers are specially encouraged to attend and renew their consecration in service to Our Eucharistic Lord, through their ministry. My hope is to meet with you after the week of June 5th either individually or as a group to answer any questions, etc. I think of the ministry of sacristan as a very important one. It resembles the time after the Annunciation and before the Nativity, in which Our Lady, prepared herself so that God could bring Jesus into this world. -

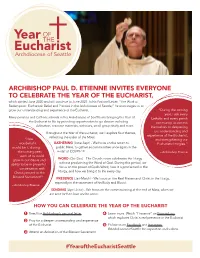

ARCHBISHOP PAUL D. ETIENNE INVITES EVERYONE to CELEBRATE the YEAR of the EUCHARIST, Which Started June 2020 and Will Continue to June 2021

OF THE Archdiocese of Seattle June 14, 2020 – June 6, 2021 ARCHBISHOP PAUL D. ETIENNE INVITES EVERYONE TO CELEBRATE THE YEAR OF THE EUCHARIST, which started June 2020 and will continue to June 2021. In his Pastoral Letter, “The Work of Redemption: Eucharistic Belief and Practice in the Archdiocese of Seattle,” he encourages us to grow our understanding and experience of the Eucharist. “During the coming year, I ask every Many parishes and Catholic schools in the Archdiocese of Seattle are bringing the Year of Catholic and every parish the Eucharist to life by providing opportunities to go deeper including community to commit Adoration, resource materials, webinars, small group study and more. themselves to deepening our understanding and Throughout the Year of the Eucharist, we’ll explore four themes, experience of the Eucharist, reflecting the order of the Mass: “How and strengthening our wonderful it GATHERING (June-Sept) - We focus on the return to Eucharistic liturgies.” would be if, during public Mass, to gather as communities once again in the the coming year, midst of COVID-19. – Archbishop Etienne each of us could grow in our desire and WORD (Oct-Dec) - The Church never celebrates the liturgy ability to be in prayerful without proclaiming the Word of God. During this period, we conversation with focus on the power of God’s Word, how it is proclaimed in the Christ, present in the liturgy, and how we bring it to life every day. Blessed Sacrament!" PRESENCE (Jan-March) - We focus on the Real Presence of Christ in the liturgy, especially in the sacrament of his Body and Blood. -

Mass and the Roman Missal, Third Typical Edition – Annotated Bibliography –

29 Mass and the Roman Missal, third typical edition – Annotated Bibliography – June 2011, revised June 2014 – Eliot Kapitan, Diocese of Springfield in Illinois UNIVERSAL AND PARTICULAR DOCUMENTS VATICAN COUNCIL II, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, 4 December 1963. See CSL, nos. 5-13 on the nature of the liturgy and its importance in the Church’s life. See CSL, nos. 14-20 on the promotion of liturgical instruction and active participation. See CSL, nos. 21-40 on the reform of the liturgy and norms for the reform. See CSL, nos. 41-46 on promotion of the liturgical life. See CSL, nos. 47-58 on the Eucharist. Available editions include: • Acta Apostolicae Sedis [Acts of the Apostolic See] 56 (1964) 97-138. • Sacrosanctum Oecumenicum Concilium Vaticanum II: Constitutiones, Decreta, Declarationes [Second Vatican Ecumenical Council: Constitutions, Decrees, Declarations] (Vatican Polyglot Press, 1966) 3-69. • Documents on the Liturgy, 1963-1979: Conciliar, Papal, and Curial Texts © 1982, International Committee on English in the Liturgy, Inc. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press. ISBN: 0-8146-1281-4. ISBN-13: 978-0-8146-1281-1. [DOL 1, nos. 1-131] • The Liturgy Documents, Volume One: Fifth Edition. Essential Documents for Parish Worship. Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2012. ISBN: 978-1-61671-062-0. • The Liturgy Documents, Volume Two: Second Edition. Essential Documents for Parish Sacramental Rites and Other Liturgies. Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2012. ISBN: 978-1-61671-027-9. LTP Universal Norms for the Liturgical Year and the General Calendar [UNLYC], 26 March 2010. Available editions include: • Every edition of the Roman Missal, Third Edition. -

June 6, 2021 the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ

JUNE 6, 2021 THE MOST HOLY BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST Sunday Mass Saturday: 5 PM - St. Joseph Sunday: 9 AM - St. Philip Sunday: 10:30 AM - St. Mary Sunday: 12 Noon In Spanish - St. Philip Daily Mass Monday: 9am - St. Joseph Wednesday: 9am - St. Philip Thursday: 9am -St. Mary Friday: 9am - St. Philip Saturday: 9am - St. Philip Confession 30 minutes before 9AM Daily Masses (Wed, Thu, Fri) Following 9AM Saturday Mass (until all are heard) 30 Minutes before Saturday 5PM Vigil 7-8PM First Thursdays during Ridgefield Adore - St. Mary & by appointment Pastoral Emergencies After Office hours: Call 360-225-8308 x 9 St. Philip Conference St. Vincent de Paul PO Box 1150 Woodland WA 98674 St. Philip Parish 430 Bozarth Ave, Woodland WA Helpline: 360-841-8734 Mailing: PO Box 2169 Woodland, Washington 98674 Priest Administrator: St. Joseph Mission Father Brian Thompson 136 North 4th St, Kalama, Washington 98625 Priest for Hispanic Ministry: Mailing: PO Box 2169 Woodland WA 98674 Father Jerry Woodman Office: 360-225-8308 St. Mary of Guadalupe Mission 1520 North 65th Ave, Ridgefield, Washington 98642 EMAIL: Mailing: PO Box 2169 Woodland WA 98674 [email protected] Parish Website: St. Mary Cemetery For Plots: 360-225-8308 www.stphilipwoodland.com Dear Parishioners, Given that Today is Corpus Christi, a day we reflect upon the gift of the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, I want to revisit a topic I wrote about my first summer in this parish, when we were hearing the Bread of Life Discourse from John 6 at Mass: How to reverently receive Holy Communion. -

Sunday, June 6, 2021 ~ the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ

BEVERLY CATHOLIC COLLABORATIVE 552 CABOT STREET ~ BEVERLY MASSACHUSETTS Sunday, June 6, 2021 ~ The Most Holy Body And Blood Of Christ The Sunday Mass Schedule Saturday Vigil 4:00 Mass at St. John the Evangelist Church Sunday Morn. 8:00 Mass at St. John the Evangelist Church Sunday Morn. 9:30 Mass at St. Margaret Church Sunday Morn. 10:00 Mass at St. Mary Star of the Sea Church Sunday Noon 12:00 Mass at St. John the Evangelist Church Eucharistic Adoration Monday thru Friday 9:00AM—10:30AM at St. Mary Star of the Sea Church June 6, 2021 The Most Holy Body And Blood Of Christ—Year B St. Mary Star of the Sea Parish, St. Margaret Parish, St. John the Evangelist Parish Rev. David C. Michael, Pastor Rev. Guy C. Sciacca, Parochial Vicar Rev. J. Paul Wargovich, Parochial Vicar Mr. Patrick O’Connor, Seminarian Rev. Mr. Michael Joens, Deacon Dr. Margaret McKinnon, Director of Religious Education / Confirmation Parish Collaborative Offices ~ 552 Cabot Street ~ Beverly MA 01915 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.beverlycatholic.com Baptisms Marriage Baptisms take place individually at each of the Catholic Engaged couples are advised to call the Rectory at least six Collaborative Parishes. months prior to their wedding date. Pre-Registration is required at each Parish. Participation in a Marriage Preparation Program is required. Confessions: Confessions will take place Saturday Morning 9:00-10:00AM At the Collaborative Office building at 552 Cabot Street In the Chapel at the rear of the building or call the Parish Office for an appointment. COLLABORATIVE PARISHES OF BEVERLY ~~ MASS SCHEDULE ST. -

Second Sunday of Advent December 9, 2007 Page Two First Sunday of Advent December 2, 2007

Website http://sij-parish.com St. John the Baptist (17th century) John the Baptist is depicted here as the Angel of the Desert, a theme which grew in popularity after the ,middle of the sixteenth century. One reason for this may be that John was the patron saint of Ivan the Terrible (ruled 1533-84), whose birthday fell on the Feast day commemorating the saint's beheading. However, the allusions here are not to John's martyrdom, but to his role as a wandering preacher. The staff in his hand signals that he has travelled a great distance, while the infant in the chalice is a token of the new life that can be gained through Christ. In the background, the tree with the axe recalls the Baptist's message, as recorded in St Luke's Gospel, about the coming judgment and the need for repentance: ‘And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: every tree therefore which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire.’ In keeping with normal icon practice, the scale is governed by spiritual rather than natural laws and the disproportionate size of the saint reflects his importance. Second Sunday of Advent December 9, 2007 Page Two First Sunday of Advent December 2, 2007 RORATY: How is Roraty celebrated today? Roraty is a pre-dawn Discovering a Polish Advent Tradition Mass that “tests” the vigilant readiness of the faithful. Day by day, participants prepare to welcome the “Lord of Light.” At the beginning of Mass, the Church is almost completely dark.