1 Menindee Lakes, Droughts and Record Low Inflows Recent Issues Of

Total Page:16

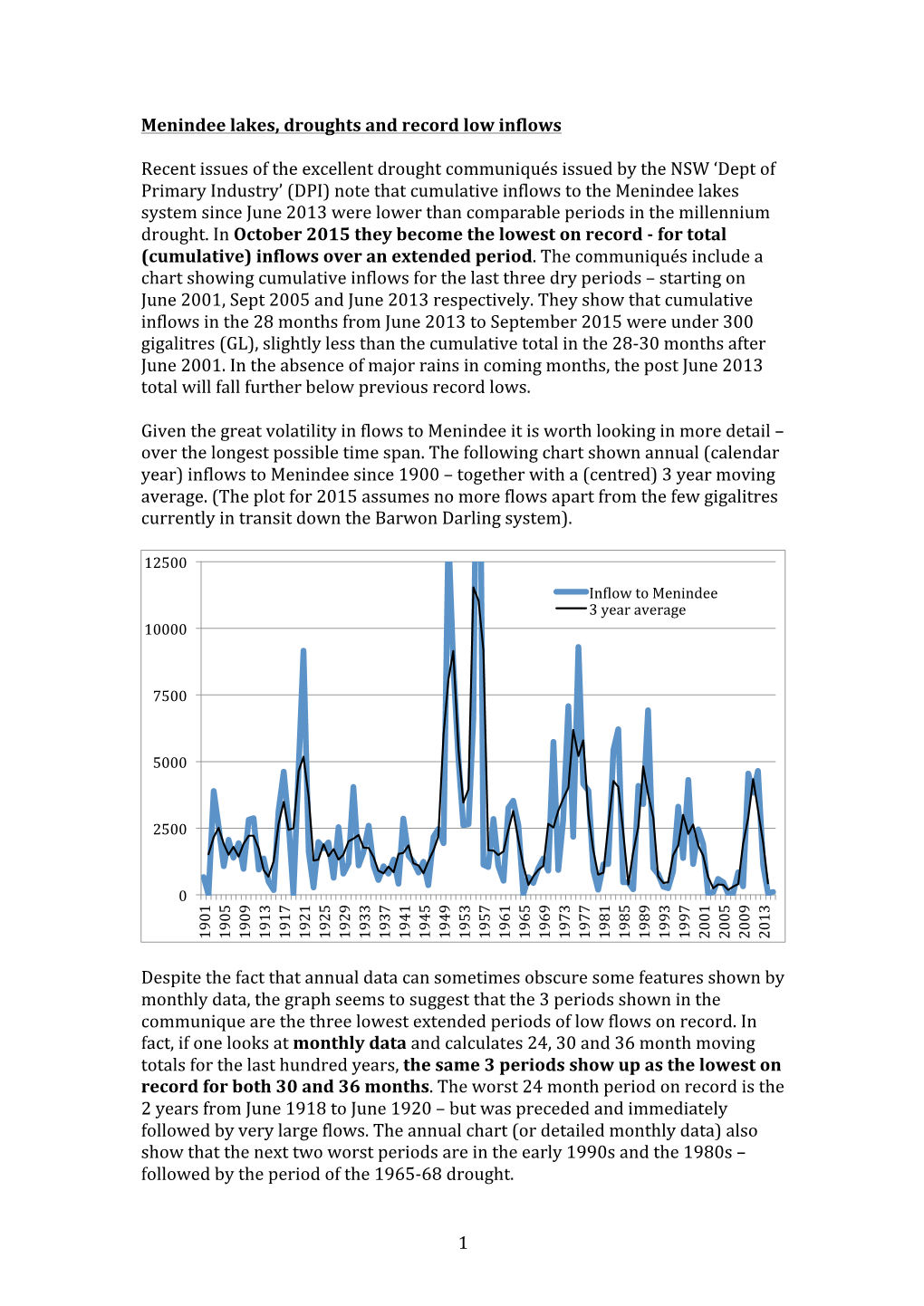

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Practice Approaches to Water Law and Management in a Developed Country Context: Examining International Policies and Principles Within a Federal Framework

BEST PRACTICE APPROACHES TO WATER LAW AND MANAGEMENT IN A DEVELOPED COUNTRY CONTEXT: EXAMINING INTERNATIONAL POLICIES AND PRINCIPLES WITHIN A FEDERAL FRAMEWORK Maureen Papas BA (Hons), M Int. Rel with M Int. Env. Law Macquarie Law School Macquarie University – Sydney Australia This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………… 2 Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Statement of Candidate ……………………………………………………………….. 8 Acknowledgement ……………………………………………………………………… 9 List of Abbreviations …………………………………………………………………… 10 Part I THE BACKGROUND …………………………………………………. 11 1.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………….. 12 1.2 Literature review………………………………………………………. 15 1.2.1 Environmental movement…………………………………………… 15 1.2.1.1 Environmental movement and key literature ………………………… 15 1.2.2 Key drivers of water reform ………………………………………………… 17 1.2.3 A new paradigm ……………………………………………………………… 18 1.2.3.1 Sustainable development and emergence of this new paradigm …….. 18 1.2.4 Early law ……………………………………………………………………… 19 1.2.4.1 International law ………………………………………………………. 19 1.3 Multilevel governance …………………………………………………………. 21 1.4 Australian context ……………………………………………………………… 21 1.4.1 History of settlement and early law …………………………………………….. 22 1.4.2 Law reform: Influence by international water law and sustainable development.23 1.5 European context ………………………………………………………………. 25 1.6 Structure and organisation of chapters ………………………………………. 27 1.7 Distinct contribution …………………………………………………………… 30 1.8 -

Submission: Inquiry Into Climate Change and the Australian

September 2008 NSW Submission to the Senate Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Inquiry into water management in the Coorong and Lower Lakes NSW Water Legislation The management of the surface water and groundwater resources of NSW, including the allocation of water entitlements, is undertaken under the Water Act, 1912 and the Water Management Act 2000. The NSW Government is progressively transitioning water management from the Water Act 1912 to the Water Management Act 2000. The vast majority of water extraction in the NSW portion of the Murray-Darling Basin is covered by statutory water sharing plans under the Water Management Act 2000. The legislation and rules in the water sharing plans provide the framework for the implementation of the COAG-agreed water reforms, including: • the provision of water entitlements specifically for the environment; • the separation of water entitlements from land; and • clearly identified tradeable water entitlements. The priority for water sharing under the legislation is: Priority 1 Water for the environment and basic landholder rights (e.g. domestic and stock rights); Priority 2 Town water supply, domestic and stock and major utility licences (e.g. power generation, major urban water supply); Priority 3 High security licences (e.g. for permanent plantings); Priority 4 General security or unregulated river licences (e.g. for irrigation of annual crops); and Priority 5 Supplementary licences (e.g. to access high flows). However, in times of severe water shortage the priority of water for domestic purposes (i.e. either under a basic landholder right or licence) is elevated above the environment. -

Attachment C

Submission No 130 INQUIRY INTO RATIONALE FOR, AND IMPACTS OF, NEW DAMS AND OTHER WATER INFRASTRUCTURE IN NSW Organisation: Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) Date Received: 6 October 2020 Post Office Box 5005 Brunswick North VIC 3056 www.mldrin.org.au ABN: 45118364079 Submission to the Inquiry into the rationale for, and impacts of, new dams and other water infrastructure in NSW (Portfolio Committee No. 7 - Planning and Environment) Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations (MLDRIN) welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission for the Inquiry into the rationale for, and impacts of, new dams and other water infrastructure in NSW to the NSW Legislative Council Portfolio Committee No. 7 - Planning and Environment. About MLDRIN MLDRIN is a confederation of Sovereign First Nations from the Southern part of the Murray Darling Basin (MDB). The group currently includes Delegates from 24 Nations across NSW, Victoria, the ACT and South Australia. Our core work includes: • Advising the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) on all matters relevant to Traditional Owners and Aboriginal people in the Southern MDB, in particular, the implementation of the Basin Plan; • Undertaking projects and having an active role in Natural Resource Management and water planning; • Providing a forum for our member Nations to keep informed, deliberate on issues, and provide feedback and advice to decision-makers across all levels of government; • Advocating for our member Nations’ rights and interests in land and water, specifically to progress the recognition of Aboriginal water rights and Cultural Flows; and, • Providing leadership and capacity building for our member Nations. MLDRIN’s Membership includes the Wiradjuri. -

Regional Water Availability Report

Regional water availability report Weekly edition 7 January 2019 waternsw.com.au Contents 1. Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 3 2. System risks ............................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Climatic Conditions ............................................................................................................................... 4 4. Southern valley based operational activities ..................................................................................... 6 4.1 Murray valley .................................................................................................................................................... 6 4.2 Lower darling valley ........................................................................................................................................ 9 4.3 Murrumbidgee valley ...................................................................................................................................... 9 5. Central valley based operational activities ..................................................................................... 14 5.1 Lachlan valley ................................................................................................................................................ 14 5.2 Macquarie valley .......................................................................................................................................... -

Menindee Lakes, the Lower Darling River and Darling Anabranch)

THE LIVING MURRAY Information Paper No. 10 IPTLM0010 Health of the River Murray Menindee Lakes, the Lower Darling River and Darling Anabranch) Contents Environmental assets within the river zone Current condition of environmental assets Reasons why some environmental assets have declined in value What can be done to restore environmental values? Existing environmental flows initiatives The system-wide perspective References Introductory Note Please note: The contents of this publication do not purport to represent the position of the Murray-Darling Basin Commission. The intention of this paper is to inform discussion for the improvement of the management of the Basin’s natural resources. 2 Environmental assets within the river zone The lower Darling River system is located at the downstream end of the River Murray system in NSW and is marked by Wentworth to the south and Menindee to the north. It encompasses the Menindee Lakes system, the Darling River below Menindee and the Great Anabranch of the Darling River (referred to hereafter as the Darling Anabranch) and associated lakes. These are iconic riverine and lake systems within the Murray-Darling Basin. In addition, a vital tributary and operating system feeds the lower River Murray. The climate of the area is semi-arid with an annual average rainfall of 200 mm at Menindee (Auld and Denham 2001) and a high potential annual evaporation of 2,335 mm (Westbrooke et al. 2001). It is hot in summer (5–46oC) and mild to cold in winter (-5–26oC). In particular, the lower Darling River system is characterised by clusters of large floodplain lakes, 103 to 15,900 ha in size, located at Menindee and along the Darling Anabranch. -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

Fish of Themenindee Lakes

Fish of the Menindee Lakes Cooperative Research Centre for Freshwater Ecology The Menindee Lakes in far-western NSW are a social, economic and environmental asset to the local community and to Australia as a whole. They represent an important breeding ground for native birds and fish and are one of the largest water storages in the Murray-Darling Basin. Well known by anglers for good fishing, the Menindee Lakes support diverse and abundant fish communities. While the most widely recognised fish in the lakes are the Golden Perch, Murray Cod and Carp, the lakes also maintain healthy populations of other native species. These species are valuable from both a diversity point of view and as food for the larger fish and the many fish-eating birds that live and breed around the lakes. We need to understand the ecology of the fish if we are to protect the biodiversity and other values of the Menindee Lakes. Improving our understanding of the fish in the region will help managers maintain the Menindee Lakes populations of native species while, hopefully, reducing the populations of introduced pests such as Carp and Gambusia. Golden Perch (Macquaria ambigua) Golden Perch are found throughout the Murray Darling Basin except at high- er altitudes, and are an important angling species. Upstream migration by adult fish is linked to spawning and is triggered by high flows from September to December. The return downstream occurs in low flows in June and July. Golden Perch mainly occur in warm, turbid, slow-flowing streams and rivers and flood plain lakes. Their colour can vary from bronze through yellow to white depending on the colour of the water. -

Far West Recreational Fishing Guide

Far West recreational fishing guide November 2014 Primefact 1045 Second on 1800 043 536. All calls will be treated as edition Recreational and Indigenous confidential and you can remain anonymous. Fisheries Unit Recreational Fishing Fee Introduction When fishing in NSW waters, both freshwater Our State's fisheries are a community-owned and saltwater, you are required by law to pay the resource. We all have a responsibility to protect NSW recreational fishing fee and carry a receipt and safeguard this natural asset for present and showing the payment of the fee. This applies future generations. when spear fishing, hand lining, hand gathering, trapping, bait collecting and prawn netting or Fishing regulations are in place to protect and when in possession of fishing gear in, on or conserve our fish stocks and aquatic habitats to adjacent to waters. ensure that fishing activities remain sustainable. All money raised by the NSW recreational fishing The Far West district lies in the far western part fee is spent on improving recreational fishing in of New South Wales and is bordered by Victoria, NSW. Some projects include: South Australia and Queensland. It is predominantly made up of slow flowing lowland • Angler facilities such as fish cleaning tables rivers and their tributaries, as well as lake and fishing platforms. systems that may be ephemeral in nature. • Stocking of freshwater fish in dams and The most renowned waterways in the Far West rivers. district are the Murray and Darling Rivers, along • Essential research on popular recreational with the Menindee Lakes system. The Murray fish species. and Darling rivers provide fishers with excellent angling opportunities for golden perch and • Enhancing compliance with fishing rules. -

1 Chapter 1: Introduction

Introduction 1 1 Chapter 1: Introduction Little is known about the vegetation dynamics of ephemeral wetlands and floodplains and the role of the seed bank in these systems (with the exception of Brock and Rogers (1998) and Capon (2003; 2005)). The majority of our knowledge of wetland and floodplain ecosystems is focussed on well-watered temperate northern hemisphere systems and tropical systems (e.g. van der Valk 1981; Leck and Simpson 1987; Junk et al. 1989). In Australia, the majority of the research into wetlands and floodplains has been undertaken on seasonal wetlands (e.g. Britton and Brock 1994; Casanova and Brock 1999b; Nicol et al. 2003), rivers with seasonal flow regimes (e.g. Pettit and Froend 2001a; 2001b; Pettit et al. 2001) and the impact of altered flow regimes in the River Murray system (e.g. Walker et al. 1994; Nielsen and Chick 1997). This study provides an insight into the vegetation dynamics of a regulated ephemeral system (the Menindee Lakes) and the role of the seed bank plays in that system. 1.1 The Seed Bank The seed bank is defined as the reserves of viable seed present in and on the soil surface (Roberts 1981) and associated litter (Simpson et al. 1989), capable of replacing adult plants (Baker 1989). The size of the seed bank, the contribution made to it by the different species and patterns of seed distribution reflect the seed production mainly by the resident plant community; although, inputs of seed from distant sources may also contribute (Simpson et al. 1989). In addition, the seed bank contains not only seeds from the preceding year but may contain seeds from many previous years (Roberts 1981); especially species that form long-term persistent seed banks (Thompson and Grime 1979). -

2019 Citizens' Inquiry Into the Health of the Barka/Darling River And

Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights 2019 Citizens’ Inquiry into the Health of the Barka/Darling River and Menindee Lakes REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 30 SEPTEMBER 2020 Michelle Maloney, Gill Boehringer, Gwynn MacCarrick, Manav Satija, Mary Graham and Ross Williams Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights an initiative of the Australian Earth Laws Alliance Michelle Maloney • Gill Boehringer Gwynn MacCarrick • Manav Satija Report Editor Michelle Maloney Mary Graham • Ross Williams Layout, Cover Design and uncredited photos: James K. Lee Cover image: Wilcannia Bridge over the Barka / Darling River. 24 March 2019. 2019 Citizens’ Inquiry © 2020 Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights (APT) into the Health of the Barka / Darling River All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review), no part of this report may be reproduced, and Menindee Lakes stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. The Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights (APT) is an initiative of the Australian Report and Earth Laws Alliance. All inquiries should be directed to the Australian Earth Laws Alliance (AELA). Recommendations https://www.earthlaws.org.au [email protected] Suggested citation: Maloney, M., Boehringer, G., MacCarrick, G., Satija, M., Graham, M. & Williams, R. (2020) 2019 Citizens’ Inquiry into the Health of the Barka / Darling River and Menindee Lakes: Report and Recommendations. Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights (APT). -

Environmental Flows in the Darling River to Support Native Fish Populations 2016–17

Environmental flows in the Darling River to support native fish populations 2016–17. 1 Environmental flows in the Darling River to support native fish populations 2016–17 Citation: Sharpe, C. and Stuart, I. (2018). Environmental flows in the Darling River to support native fish populations. CPS Enviro report to The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Acknowledgements: This project was funded by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. From NSW OEH; Paula D’Santos, Sascha Healy and Paul Childs provided tireless leadership in flow planning and coordination to the lower Darling River and Great Darling Anabranch throughout 2016–17 to promote the maintenance and recovery of fish populations in the Darling River and Southern-Connected Basin. From NSW DPI Fisheries; Iain Ellis provided expert ecological input and support to flow planning, agency and community engagement of the project findings. From CEWO Alana Wilkes, Irene Wegener, Hilton Taylor, Hilary Johnson, and Sean Kelly and from the Murray–Darling Basin Authority, Adam Sluggett, Adam McLean, Kerry Greenwood, John Waterworth and Tristan Skinner provided operational guidelines for hydrograph development and delivery to the lower Darling River and Great Darling Anabranch. From CPS Enviro, Sheridan Stephens for project administration and Steve Campbell-Brown and Mark Henderson for technical support in field sampling the Darling River (Walgett-Wentworth), Great Darling Anabranch and in the Menindee Lakes. We thank landholders along the Darling River and Anabranch for access through their properties. This work was conducted under NSW Fisheries Permit P12/0004 and Griffith University ACEC ENV0414AEC. Disclaimer: The results and comments contained in this report have been provided on the basis that the recipient assumes the sole responsibility for the interpretation and application of them. -

Inquiry Into Flood Mitigation Infrastructure in Victoria Parliament of Victoria Environment and Natural Resources Committee

TRIM Ref: D11/23166 Inquiry into flood mitigation infrastructure in Victoria Parliament of Victoria Environment and Natural Resources Committee The terms of reference direct the Committee to investigate matters relating to flood mitigation infrastructure in Victoria, with particular reference to: a. Best practice and emerging technology for flood mitigation and monitoring infrastructure including river gauges b. Management of levees in Victoria, including ownership, responsibility and maintenance on both public and private land c. Waterways management, including the nature and extent of vegetation clearing activities within waterways and their general maintenance d. Identifying those entities and individuals having ownership of waterways and the responsibility for their clearing and their maintenance e. The extent to which, if any, local knowledge of residents is employed in effecting waterways clearing and maintenance Submission by the Murray‐Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) Overview MDBA manages the operation of the dams, storages and weirs of the River Murray System in accordance with the Water Act 2007 (Schedule 1, The Murray‐Darling Basin Agreement). Although this infrastructure has not been designed to specifically mitigate floods, significant mitigation can occur as headwater storages fill and spill. The operation of individual structures must firstly safeguard the security of that structure and secondly fulfil its primary function of securing water supply. To the extent possible, and subject to meeting these primary objectives,