Thomas Can't Be Faulted for Teary Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power Outages Blamed on Winds TUXEDO FREE POLICY FLO’S Cfke Decorating Supplies Inc

2(1 KVKNING HKRALI). Sal . Orl 25. ISDU MaiirhrBtpr 1 ^ MANCHESTER NAS IT! Fair Fair tonight; becoming MAY WE SUGGEST •WEATHER cloudy. Detail's on page 2. BUSINESS DIRECTORY GUIDE FOR jPLAnERS A SALAOS . \m YGUR HULIOAY WEEKENO;; J h u e • ITAUM IfICIALTIlI • H O N B ^ Plli Vol. C, No. 23 — Manchester, Conn., Monday, October 27, 1980 YOVK HOMETOinS yEfTSPAPER Since 1881 . 20(l I ^ tt MANCHESTER AND SURROUNDING • Dili ITEM! •AirriPAtTO i ^ou otaii • CATfAIM •naUAN HAAD GAUtT M UD a UHt®* Marinated Mushroom, Inc. W* c»(fY 10 1 p>*l VICINITY The rh*n t AM. "(3 IBil of &a&i of •Ki'lc'i DMLY FEATURING THIS WEElT .. 182 South Miln St. • Manchost^ Formal plan sought for mill rehab SwvlM itlll mMnt iOmithlnB to U6 — tnd Mrvlot iR tini ipiodino inowflf By MARTIN KEARNS Another possibility is that town of quality ot the area is maintained. The CUNLIFFE AUTO BODY tlrrw with you to help you lolM t th# right ptint flnlih for ih tt JoG you ro plan- Herald llrporler fices in the now-crowded municipal complex is one of a dozen historic ' ■ “i nlng. Sat U6 tor paint and aarvioa whan you plan your nairt prolact. building could be relocated in the sites included in the National ic- •vr' MANCHESTKK- Town officials clock lower mill. Town officials, Register of Historic Places, and ”24 have asked a New York developer to however, have not taken any position redevelopment would not be allowed submit a formal proposal for the on Rosen’s of£er''to include the of to change its appearance. -

Scott Merkin, MLB.Com

WHITE SOX HEADLINES OF JULY 10, 2018 “Inbox: What are White Sox plans for Deadline?”… Scott Merkin, MLB.com “Column: Reunion of '93 White Sox brings memories of growing pains of the past” … Paul Sullivan, Chicago Tribune “Column: Fans aren't only ones making questionable All-Star selections”… Paul Sullivan, Chicago Tribune “Series preview: Cardinals at White Sox” … Paul Sullivan, Chicago Tribune “Todd Frazier put on 10-day DL for 2nd time this season”… Mike Fitzpatrick, Sun-Times “White Sox claim Twins outfielder Ryan LaMarre off waivers” … Satchel Price, Sun-Times “Daniel Palka packing some punch in White Sox’ lineup” … Daryl Van Schouwen, Sun-Times “White Sox prospect Alex Call is interested in the right kind of numbers” … James Fegan, The Athletic “TA30: The MLB power rankings have the Cubs floating up — and a pileup in the basement” … Levi Weaver, The Athletic “Sox is singular: Have the White Sox hit rock bottom yet? Asking for some friends” … Jim Margualus, The Athletic “Rosenthal: The five biggest lies baseball people tell during trading season” … Ken Rosenthal, The Athletic Inbox: What are White Sox plans for Deadline? Beat reporter Scott Merkin answers questions from fans By Scott Merkin / MLB.com / July 9, 2018 I hear rumblings that Avisail Garcia may be on the trading block. I feel this would be a huge mistake. Avi may finally be paying dividends for years to come. -- Sol, New York Garcia becomes one of those interesting decisions for Rick Hahn and Ken Williams in that he's 27 and is loaded with talent, but the team only has one more year of contractual control over him after 2018. -

AROUND the HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition

NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM, INC. 25 Main Street, Cooperstown, NY 13326-0590 Phone: (607) 547-0215 Fax: (607)547-2044 Website Address – baseballhall.org E-Mail – [email protected] NEWS Brad Horn, Vice President, Communications & Education Craig Muder, Director, Communications Matt Kelly, Communications Specialist P R E S E R V I N G H ISTORY . H O N O R I N G E XCELLENCE . C O N N E C T I N G G ENERATIONS . AROUND THE HORN News & Notes from the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum September Edition Sept. 17, 2015 volume 22, issue 8 FRICK AWARD BALLOT VOTING UNDER WAY The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s Ford C. Frick Award is presented annually since 1978 by the Museum for excellence in baseball broadcasting…Annual winners are announced as part of the Baseball Winter Meetings each year, while awardees are presented with their honor the following summer during Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, New York…Following changes to the voting regulations implemented by the Hall of Fame’s Board of Directors in the summer of 2013, the selection process reflects an era-committee system where eligible candidates are grouped together by years of most significant contributions of their broadcasting careers… The totality of each candidate’s career will be considered, though the era in which the broadcaster is deemed to have had the most significant impact will be determined by a Hall of Fame research team…The three cycles reflect eras of major transformations in broadcasting and media: The “Broadcasting Dawn Era” – to be voted on this fall, announced in December at the Winter Meetings and presented at the Hall of Fame Awards Presentation in 2016 – will consider candidates who contributed to the early days of baseball broadcasting, from its origins through the early-1950s. -

Officials Back $39 Board Increase by VIVIAN B

'Inside Today The Commission On Higher The student government votes The long-awaited report on the The Hartford Times goes out U.S.Sen Lowell Weicker, Education recommends that the today on whether to sent its possible health hazards of of business after 159 years, R.-Conn.. campaigns at UConn. legislature cut about $300,000 chairman to a convention in dormitory roof tarring is not leaving about 450 persons with- Stories and picture page 6. from UConn's 1977-78 budget. Kansas City, Mo. at a cost of satisfactory and another report out jobs. Story page 5. Story page 4. ■ $330 Story page 4. is ordered. Story page 5. tihmttttttntt lathj (Eamtma Serving Storrs Since 1896 VOL. LXXX NO. 33 STORRS. CONNECTICUT THURSDAY, OCTOBER 21, 1976 Officials back $39 board increase By VIVIAN B. MARTIN • said Wednesday the the fee hike was set ed in arriving at the increase proposal. possible to cut another part of the A $39 per semester increase for and recommended by a committee organ- Adams has called the $39 figure "a bare budget." he said. "If we really wanted to students eating in University-run dining ized to review the fees. The recommend- bones minimum." take risks, we could deplete the reserve halls has been initially endorsed by the ed fee is tentative, and may be increased "The people involved with the fee fund, but that's not too expedient." he administration, UConn officials said or decreased. Wiggins said. review have worked out the budget and said. Wednesday. Students in dining halls currently pay all the explanations for increases." 'I know students are going to gripe, but Leonard Hodgson, director of food $335 a semester. -

Noriega Blames Revolt on U.S

VOL. XXIII NO. 29 THURSDAY , OCTOBER 5, 1989 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY’S Auburn prof discusses date rape Wednesday By MAGGIE MCCLOSKEY olence, aggression, fear, and Staff Reporter harm. “When you put the word date’ Acquaintance rape and and the word rape’ together, “ Crossed Signals on a Saturday they don’t overlap, they don’t Night: Straight Talk About match. It’s very often the case Dating” were the topics of a that people will not talk about lecture given Wednesday night date rape.” by Barry Burkhart of Auburn Studies at Auburn and a num University. ber of other universities have Burkhart opened his talk by shown that a woman is 50 explaining the difficulty found times more likely to be raped in discussing acquaintance by someone she knows than by rape because the topic does not a stranger. Between the ages of lend itself to clear communica 15-25, 15-20% of all women tion. will have at least one instance Opposing images of the word of forced sexual intercourse. ‘date’ and the word ’rape’ also In order to determine the complicate a universal under causes of the prevalence of ac standing of date rape, quaintance rape, Burkhart Burkhart said. questioned why men and Burkhart claimed that the women encounter harm as the Twist and shout r„ word ‘date’ has relatively outcome of a relationship. pleasant connotations; B urkhart said, “ One of the These students contort their bodies playing Twister in a contest in Angela Athletic facility as part of whereas, the word Tape’ con Saint Mary's Fall Fest. -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Sunday's Lineup 2018 WORLD SERIES QUEST BEGINS TODAY

The Official News of the 2018 Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp Sunday, January 21, 2018 2018 WORLD SERIES QUEST BEGINS TODAY Sunday’s The hard work and relentless dedica- “It is about how we bring families, Lineup tion needed to be a winning team and neighbors, friends, business associates, gain a postseason berth begins long be- and even strangers together. fore the crowds are in the stands for “But we all know it is the play on the Opening Day. It begins on the practice field that is the spark of it all.” fields, in the classroom, and in the The Indians won an American League 7:00 - 8:25 Breakfast at the complex weight room. -best 102 games in 2017 and are poised Today marks that beginning, when the to be one of the top teams in 2018 due to 7:30 - 8:00 Bat selection 2018 Cleveland Indians Fantasy Camp its deeply talented core of players, award players make the first footprints at the -winning front office executives, com- Tribe’s Player Development Complex mitted ownership, and one of the best - if 8:30 - 8:55 Stretching on agility field here in Goodyear, AZ. not the best - managers in all of baseball Nestled in the scenic views of the Es- in Terry Francona. 9:00 -10:00 Instructional Clinics on fields trella Mountains just west of Phoenix, Named AL Manager of the year in the complex features six full practice both 2013 and 2016, the Tribe skipper fields, two half practice fields, an agility finished second for the award in 2017. -

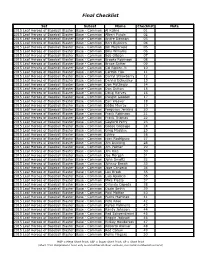

Final Checklist

Final Checklist Set Subset Name Checklist Note 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Al Kaline 01 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Albert Pujols 02 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Andre Dawson 03 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bert Blyleven 04 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bill Mazeroski 05 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Billy Williams 06 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bob Gibson 07 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Brooks Robinson 08 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Bruce Sutter 09 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Cal Ripken Jr. 10 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Carlton Fisk 11 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Darryl Strawberry 12 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dennis Eckersley 13 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Mattingly 14 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Don Sutton 15 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Doug Harvey 16 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Dwight Gooden 17 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Earl Weaver 18 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Eddie Murray 19 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Ferguson Jenkins 20 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Robinson 21 2015 Leaf Heroes of Baseball Blaster Base - Common Frank Thomas 22 2015 Leaf Heroes of -

Chicago White Sox Charities Lots 1-52

CHICAGO WHITE SOX CHARITIES LOTS 1-52 Chicago White Sox Charities (CWSC) was launched in 1990 to support the Chicagoland community. CWSC provides annual financial, in-kind and emotional support to hundreds of Chicago-based organizations, including those who lead the fight against cancer and are dedicated to improving the lives of Chicago’s youth through education and health and well- ness programs and offer support to children and families in crisis. In the past year, CWSC awarded $2 million in grants and other donations. Recent contributions moved the team’s non-profit arm to more than $25 million in cumulative giving since its inception in 1990. Additional information about CWSC is available at whitesoxcharities.org. 1 Jim Rivera autographed Chicago White Sox 1959 style throwback jersey. Top of the line flannel jersey by Mitchell & Ness (size 44) is done in 1959 style and has “1959 Nellie Fox” embroi- dered on the front tail. The num- ber “7” appears on both the back and right sleeve (modified by the White Sox with outline of a “2” below). Signed “Jim Rivera” on the front in black marker rating 8 out of 10. No visible wear and 2 original retail tags remain affixed 1 to collar tag. Includes LOA from Chicago White Sox: EX/MT-NM 2 Billy Pierce c.2000s Chicago White Sox ($150-$250) professional model jersey and booklet. Includes pinstriped jersey done by the team for use at Old- Timers or tribute event has “Sox” team logo on the left front chest and number “19” on right. Num- ber also appears on the back. -

Columbia Chronicle College Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 2-29-1988 Columbia Chronicle (02/29/1988) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (02/29/1988)" (February 29, 1988). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/239 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. · , Columbia 'Chronicle , Vo lume 20, Num Iwr 1 Monday " February 29 1988 Columbia College, Chicago New revisions could lower GSl's for dependent students By Lee Bey drcn in that family attending college to "One error can cau$C a six-week Ide determine ira student was eligible for a lay)." he said. "If a student misses the N~w financial aid cligibilil)' guide GSL. (Illinois State Scholarship) deadline. he Jines and careless fili ng of financial aid "Now, under the federal Higher Ed- could lose $3, 100," forms could cost Columbia students ucation Act of 1986, most of which 01ino said government cutbacks in thousarx:ls of dollars during the 1988- . went into effect last fall . counselors non-repayable grant money along wilh 1989 academic year. Director of Finan must look at other forms of revenue and .