America's Miracle Man in Vietnam Roundtable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Issue of Saber

1st Cavalry Division Association Non-Profit Organization 302 N. Main St. US. Postage PAID Copperas Cove, Texas 76522-1703 West, TX 76691 Change Service Requested Permit No. 39 SABER Published By and For the Veterans of the Famous 1st Cavalry Division VOLUME 70 NUMBER 4 Website: www.1CDA.org JULY / AUGUST 2021 It is summer and HORSE DETACHMENT by CPT Siddiq Hasan, Commander THE PRESIDENT’S CORNER vacation time for many of us. Cathy and are in The Horse Cavalry Detachment rode the “charge with sabers high” for this Allen Norris summer’s Change of Command and retirement ceremonies! Thankfully, this (704) 641-6203 the final planning stage [email protected] for our trip to Maine. year’s extended spring showers brought the Horse Detachment tall green pastures We were going to go for the horses to graze when not training. last year; however, the Maine authorities required either a negative test for Covid Things at the Horse Detachment are getting back into a regular swing of things or 14 days quarantine upon arrival. Tests were not readily available last summer as communities around the state begin to open and request the HCD to support and being stuck in a hotel 14 days for a 10-day vacation seemed excessive, so we various events. In June we supported the Buckholts Cotton Festival, the Buffalo cancelled. Thankfully we were able to get our deposits back. Soldier Marker Dedication, and 1CD Army Birthday Cake Cutting to name a few. Not only was our vacation cancelled but so were our Reunion and Veterans Day The Horse Detachment bid a fond farewell and good luck to 1SG Murillo and ceremonies. -

Günter Bischof “Busy with Refugee Work” Joseph Buttinger, Muriel Gardiner, and the Saving of Austrian Refugees, 1940–1941

Aus: Zeithistoriker – Archivar – Aufklärer. Festschrift für Winfried R. Garscha, hrsg. v. Claudia Kuretsidis- Haider und Christine Schindler im Auftrag des Dokumentationsarchivs des österreichischen Widerstandes und der Zentralen österreichischen Foschungsstelle Nachkriegsjustiz, Wien 2017 115 Günter Bischof “Busy with Refugee Work” Joseph Buttinger, Muriel Gardiner, and the Saving of Austrian Refugees, 1940–1941 At a time when Austria is experiencing political turbulences over the current “refugee crisis” of Syrian, Near Eastern and African asylum seekers, looking for a safe haven in Europe from the political turmoil in their regions, it might be worthwhile remembering that there were times in the twentieth century when Austrian refugees survived in similarly tumultuous situations with sup- port from the “kindness of strangers.” Joseph Buttinger (1906–1992) and his wealthy American wife Muriel Gardiner (1901–1965) personally helped hun- dreds of Austrian Socialists and Jews (often both) persecuted by the Dollfuss- Schuschnigg regimes and the Nazis to get out of Austria – and later Europe – to save their lives. They were generous in helping to provide the necessary immi- gration papers and funds for refugees to start a new life in the United States. After the end of World War II they supported a hundred or so families with CARE packages over several years. The Buttingers became shining examples of professional and humanitarian refugee workers. Their empathetic “refugee work” stands as a paragon of humanitarian aid for our days as well. Joseph Buttinger was born in Bavaria in 1906 and grew up in great poverty in Upper Austria. His father worked in various odd jobs and as a miner and fought on the Dolomite front in World War I; he died after being wounded. -

Comedy Therapy

VFW’S HURRICANE DISASTER RELIEF TET 50 YEARS LATER OFFENSIVE An artist emerges from the trenches of WWI COMEDYAS THERAPY Leading the way in supporting those who lead the way. USAA is proud to join forces with the Veterans of Foreign Wars in helping support veterans and their families. USAA means United Services Automobile Association and its affiliates. The VFW receives financial support for this sponsorship. © 2017 USAA. 237701-0317 VFW’S HURRICANE DISASTER RELIEF TET 50 YEARS LATER OFFENSIVE An artist emerges from the trenches of WWI COMEDYAS THERAPY JANUARY 2018 Vol. 105 No. 4 COVER PHOTO: An M-60 machine gunner with 2nd Bn., 5th Marines, readies himself for another assault during the COMEDY HEALS Battle of Hue during the Tet Offensive in 20 A VFW member in New York started a nonprofit that offers veterans February 1968. Strapped to his helmet is a a creative artistic outlet. One component is a stand-up comedy work- wrench for his gun, a first-aid kit and what appears to be a vial of gun oil. If any VFW shop hosted by a Post on Long Island. BY KARI WILLIAMS magazine readers know the identity of this Marine, please contact us with details at [email protected]. Photo by Don ‘A LOT OF DEVASTATION’ McCullin/Contact Press Images. After hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria 26 ON THE COVER roared through Texas, Florida and Puer- 14 to Rico last fall, VFW Posts from around Tet Offensive the nation rallied to aid those affected. 20 Comedy Heals Meanwhile, VFW National Headquar- 26 Hurricane Disaster Relief ters had raised nearly $250,000 in finan- 32 An Artist Emerges cial support through the end of October. -

J a C K Kirb Y C Olle C T Or F If T Y- Nine $ 10

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-NINE $10 FIFTY-NINE COLLECTOR KIRBY JACK IT CAN’T BE! BUT IT IS! I’VE DISCOVERED... ...THE AND NOTHING WILL EVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!! 95 A TREASURE TROVE OF RARITIES BY THE “KING” OF COMICS! Contents THE OLD(?) The Kirby Vault! OPENING SHOT . .2 (is a boycott right for you?) KIRBY OBSCURA . .4 (Barry Forshaw’s alarmed) ISSUE #59, SUMMER 2012 C o l l e c t o r JACK F.A.Q.s . .7 (Mark Evanier on inkers and THE WONDER YEARS) AUTEUR THEORY OF COMICS . .11 (Arlen Schumer on who and what makes a comic book) KIRBY KINETICS . .27 (Norris Burroughs’ new column is anything but marginal) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .30 (the shape of shields to come) FOUNDATIONS . .32 (ever seen these Kirby covers?) INFLUENCEES . .38 (Don Glut shows us a possible devil in the details) INNERVIEW . .40 (Scott Fresina tells us what really went on in the Kirby household) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .42 (Adam McGovern & an occult fave) CUT-UPS . .45 (Steven Brower on Jack’s collages) GALLERY 1 . .49 (Kirby collages in FULL-COLOR) UNEARTHED . .54 (bootleg Kirby album covers) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .55 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) GALLERY 2 . .56 (unused DC artwork) TRIBUTE . .64 (the 2011 Kirby Tribute Panel) GALLERY 3 . .78 (a go-go girl from SOUL LOVE) UNEARTHED . .88 (Kirby’s Someday Funnies) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .90 PARTING SHOT . .100 Front cover inks: JOE SINNOTT Back cover inks: DON HECK Back cover colors: JACK KIRBY (an unused 1966 promotional piece, courtesy of Heritage Auctions) This issue would not have been If you’re viewing a Digital possible without the help of the JACK Edition of this publication, KIRBY MUSEUM & RESEARCH CENTER (www.kirbymuseum.org) and PLEASE READ THIS: www.whatifkirby.com—thanks! This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

Signature Redacted Sign Ature Redacted

VIET NAM'S STRATEGIC HAMLET: DEVELOPMENT AND DENOUEMENT By Leland E. Prentice Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY August 1969 Signature Redacted Signature of Author D&partment of Political Science Certified by Signature Redacted Tht1is S ulepervJsor Sign ature Redacted Accepted by Chairman, Departmental Commi ttee on Graduate Students Archives iAss. INST. rtEC. OCT 2 9 1969 rA RI S 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 MIT Libraries http://libraries.mit.edu/ask DISCLAIMER NOTICE Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. Thank you. Some pages in the original document contain text that runs off the edge of the page. I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As in most research, there are certain individuals who contribute to a study but do not appear on the title page. I am personally indebted to many individuals for their contributions throughout my period of study at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. There are certain individuals to whom I wish to extend my personal appreciation for their efforts to aid me not only in the writing of this thesis, but also in the completion of my academic program. Professors William W. Kaufmann and Donald Blackmer greatly assisted me in my development as a student of political science. Colonel Marshall 0. Becker has relieved me of numerous responsibilities, to the burden of my fellow staff members, in order that I might complete this study. -

MLJ's Silver Age Revivals

ASK MR. SHUTTSILVER AGE “Too Many Super Heroes” doesn’t really do this group justice MLJ’s Silver Age revivals by CRAIG SHUTT Dear Mr. Silver Age, I’m a big fan of The Fly and Fly Girl, and I understand they were members of a super-hero team. Do you know who else was a member? Betty C. Riverdale Mr. Silver Age says: I sure do, Bets, and you’ll be happy to hear that a few of those stalwart super-heroes are returning to the pages of DC’s comic books. The first to arrive are The Shield, The Web, The Hangman, and Inferno. They’re being touted as the heroes from Archie Comics’ short-lived Red Circle line of the 1980s, but they all got their start much earlier than that, including brief appearances in the Silver Age. During those halcyon days, they all were members of (or at least tried out for) The Mighty Crusaders! And, if the new adventures prove popular, there are plenty more heroes awaiting their own revival. The Mighty Crusaders, Archie’s response to the mid-1960s success of super-hero teams, got their start in Fly Man #31 (May 65). The team consisted of The Shield, Black Hood, The Comet, Fly Man (né The Fly), and Fly Girl. The first three were revived versions of Golden Age characters, while the latter two starred in their own Silver Age series. The heroes teamed up for several issues and then began individual back-up adventures through #39. They also starred in seven issues of Mighty Crusaders starting with #1 (Nov 65) and then took over Fly Man in various combinations, when it became Mighty Comics with #40 (Nov 66). -

A Study Guide by Fiona Hall

© ATOM 2016 A STUDY GUIDE BY FIONA HALL http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-939-9 http://theeducationshop.com.au friendship grew between Australians and Asians. OVERVIEW Those bonds remained and after the war, Team veterans helped Vietnamese refugees find a new ‘Vietnam: The War That Made Australia’ is a major home in Australia. In doing so, this unsung unit of 3-part series that tells the extraordinary story of the soldiers played their part in transforming Australia Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (aka ‘The into a multicultural nation. Team’), an elite unit of soldiers sent to Vietnam in 1962 to train the South Vietnamese Army to fight The series opens in 1962, when the Cold War is at the communists. its height and communist forces threaten to over- run South East Asia. Red paranoia stalks Australia The first Australian soldiers in and the last to leave, and many fear that Asian communists will be on The Team would become the most highly deco- our shores if not stopped. Australia responds by rated unit of the war with four Victoria Crosses to sending the Australian Army Training Team to its name. It’s a little-known story and many of its Vietnam to train the South Vietnamese Army. The veterans are talking for the first time. Revelatory US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is waging its and moving, the Vietnam War they experienced own war, using native tribesmen to form clan- is unlike that of any other Australians who fought destine guerrilla units, and seizes on the Team’s there. -

I^Isitorical Hs^Gociation

American i^isitorical Hs^gociation EIGHTY-THIRD ANNUAL MEETING ifc NEW YORK CITY HEADQUARTERS: STATLER HILTON HOTEL DECEMBER 28, 29, 30 Bring this program with you Extra copies SO cents Virginia: Bourbonism to Byrd, 1870-1925 By Allen W. Moger, Professor of History, Washington and Lee Uni versity. Approx. 400 pp., illiis., index. 63/^ x ps/^. L.C. 68-8yp8. $y.yo This general history of Virginia from its restoration to the Union in 1870 to the election of Harry Flood Byrd as governor in 1925 illuminates the tools and conceptions of government which originated during the impoverished and bitter years after the Civil War and which remained useful and vital well into the twentieth century. Westmoreland Davis: Virginia Planter—Politician, 1859-1942 By Jack Temple Kirby, Assistant Professor of History, Miami University, via, 21 y pp., fontis., ilins., index. 6 x p L.C. 68-22yyo. 55.75 Mr. Kirby's biography of this distinguished twentieth-century Virginia gov ernor, reformer, agricultural leader, lobbyist, publisher, and opponent of the state Democratic machine is a fresh interpretation of the progressive era in Virginia. Westmoreland Davis's life illuminates the role of agrarians and the influence of scientific methodology, efficiency techniques, and Democratic fac tionalism in Virginia's government as well as the rise and early career of Harry Byrd. Old Virginia Restored: An Interpretation of the Progressive Impulse, 1870-1930 By Raym )nd H. Puli.ey, Assistant Professor of History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Approx. 224 pp., illits. 6 x p. L.C. 68-8ypp. Price to be announced. -

Extensions of Remarks

September 22, 1976 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 32039 ative agreement or guarantee or commitment Directs the Secretary of the Treasury to taining to the development and revision of to guarantee with the Administration under forward certain identifying information on land and resouTce management plans. this section during such time as such officer such vehicles to the Secretary of Transporta Revises provisions relating to sale of for or employee discharged duties or responsibil tion who shall forward such information to est products found upon national forest ities under this section." the appropriate State agency responsible for landis. On Page 126, line 3, strike out "(4)" and motor vehicle registration. Prohibits the return to the public domain insert " ( 5) ". H.R. 15358. August 31, 1976. Public Works of na tiona! forest lands other than by Act By Mr. OTTINGER: and Transportation. Amends the Appalachian of Congress. (Amendment to the amendment in the Regional Development Act of 1965 to increase Abolishes the National Forest Reservation nature of a substlrtute offered by Mr. TEAGUE.) the amount of available Federal assistance as Commission. In section 19(c) of the Federal Nonnuclear a percentage of the total costs of Appalachian H.R. 15364. August 31, 1976. Judiciary; Energy Research and Development Act of development highway projects. Standards of Official Conduct. Requires can 1974 (as added by the first section of the H.R. 15359. August 31 , 1976. Science and didates for Federal office, Members of the amendment in the nature of a substitute of Technology; Atomic Energy. Requires the Congress, and certain officers and employees fered by Mr. -

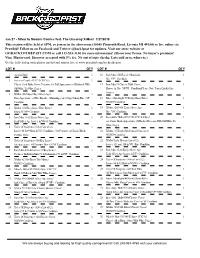

Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

Jan 27 - Silver to Modern Comics feat. The Uncanny X-Men! 1/27/2018 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! (Showroom Terms: No buyer's premium! Visa, Mastercard, Discover accepted with 5% fee. No out of state checks. Lots sold as-is, where-is.) Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Info 1 16 Iron Man #10/Classic Mandarin. 1 Nice F/F+ Condition. 2 Forever People #1/1971 CGC 6.5. 1 Classic Jack Kirby Cover. Features 1st Full Appearance of Darkseid With 17 Iron Man #9/Classic Hulk Cover. 1 Off-White To White Pages. Shows As Nice VF/VF+ Condition Please Note Paper Quality Has Tanned. 3 X-Men #28/Super Key Silver Age! 1 First Appearance of The Banshee! Humdinger of a Copy! Sharp Fine+/VF 18 Marvel Spotlight #7/Early Ghost Rider. 1 Condition. VG/VG+ Condition. 4 X-Men #108/Key Issue/First Byrne! 1 19 X-Men #26/1966 Early Silver Age. 1 Sharp VF/VF+ Condition. Nice VG+ Condition. 5 Iron Man 11-12/Early Silver Age. 1 20 Incredible Hulk #271/1982 CGC 6.5 Key! 1 Early Silver Age Issues in VG+/F Condition. 1st Comic Book Appearance Of Rocket Raccoon With Off-White To White Pages. -

The Vietnam War, Public Opinion and American Culture

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature The Vietnam War, Public Opinion and American Culture Diploma Thesis Brno2008 Supervisedby:Writtenby: Mgr.ZdeněkJaník,M.A.ZuzanaHodboďová Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen ty prameny,které jsouuvedenévseznamuliteratury. Souhlasím,abypráce byla uložena vinformačním systému (IS) Masarykovyuniverzity vBrně, popř. vknihovně Pedagogické fakulty MU a aby byla využita ke studijním účelům. Declaration: I proclaim that mydiploma thesis is a piece of individual writingand that I used only thesourcesthatarecitedinbibliographylist. I agree with this diploma thesis beingstoredinthe InformationSystem of the Masaryk University, eventually in the Library of the Faculty of Education, and with its being takenadvantageforacademic purposes. 16 th April2008,Brno………………………………………….... Poděkování: Ráda bych poděkovala panu Mgr. Zdeňku Janíkovi, M.A., vedoucímu mé diplomové práce, za jehocenné radya připomínky,které přispělyke konečné podobě tétopráce. Dále bychráda využila příležitosti a toutocestoupoděkovala svým rodičům za jejich pomocanevyčerpatelnoupodporu,kteroumivěnovalinejenvdoběmýchstudií. Acknowledgements: I wouldlike tothankto Mgr.ZdeněkJaník,M.A.,the supervisor of my diploma thesis, for his valuable advice andcomments that contributedtothe final form of this work. Furthermore,I wouldlike touse the opportunityandthanks tomyparents for their help andinexhaustiblesupportwhichtheydedicatedmenotonlyatthe timeof