The La Venta Olmec Support Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ixhuatlán Del Sureste, Ver

MUNICIPIO DE IXHUATLÁN DEL SURESTE, VER. FISCALIZACIÓN SUPERIOR DE LA CUENTA PÚBLICA 2013 RESULTADO DE LA FASE DE COMPROBACIÓN ÍNDICE PÁGS. INFORMACIÓN GENERAL DEL AYUNTAMIENTO 1. FUNDAMENTACIÓN ............................................................................................................................ 415 2. OBJETIVO DE LA FISCALIZACIÓN SUPERIOR .................................................................................. 415 3. ÁREAS REVISADAS ............................................................................................................................ 415 4. RESULTADO DE LA REVISIÓN DE LA CUENTA PÚBLICA ................................................................. 416 4.1. EVALUACIÓN DE LA GESTIÓN FINANCIERA ................................................................. 416 4.1.1. CUMPLIMIENTO DE LAS DISPOSICIONES APLICABLES AL EJERCICIO DE LOS RECURSOS PÚBLICOS................................................................................................... 416 4.1.2. ANÁLISIS PRESUPUESTAL ............................................................................................ 416 4.1.2.1. INGRESOS Y EGRESOS ......................................................................................... 416 4.2. CUMPLIMIENTO DE LOS OBJETIVOS Y METAS DE LOS PROGRAMAS APLICADOS . 420 4.2.1. INGRESOS PROPIOS ...................................................................................................... 420 4.2.2. FONDO PARA LA INFRAESTRUCTURA SOCIAL MUNICIPAL (FISM) ......................... -

Nanchital Ver Dx 2010.Pdf

NANCHITAL 2008-2010 H. Ayuntamiento del Municipio de Nanchital de Lázaro Cárdenas del Rio, Veracruz. Presidenta Municipal Constitucional Profa. María Esther Ríco Martínez Comisión de Equidad de Género Prof. Roosevelt Garrido Carreño Directora de la IMMN Lic. Maribel Rodríguez Aguirre PROYECTO FODEIMM 2010 Equipo consultor: Equifonía Coletivo por la Cidadania, Autonomia y Libertad de las Mujeres. A.C Lic. Karina Soto Zarasas Mtra. Araceli González Saavedra Dra. Samana Vergara Lope Tristan Lic. Marykarly Hernandez Cabrera Nanchital de Lázaro Cárdenas del Rio, Veracruz, 30 de noviembre 2010 1 NANCHITAL 2008-2010 Página Carta de la directora 3 Carta de la Presidenta 4 Presentación 7 INTRODUCCIÓN 9 MARCO TEÓRICO 11 Metodología 29 Perfil sociodemográfico del municipio de Nanchital de Lázaro Cárdenas 33 del Río, Veracruz Diagnóstico de la condición de las mujeres y su posición de género en 49 el municipio de Nanchital Informes de acciones para las mujeres en el ayuntamiento de Nanchital 95 Conclusiones 103 Recomendaciones 105 Bibliografía 108 Anexos 109 2 NANCHITAL 2008-2010 La cultura en tiempos pasados marcaba fuertemente la diferencia entre los géneros, anteriormente la mujer solo tenía acceso a la vida privada, es decir se dedicaban a la casa y la familia solo podía actuar dentro del hogar y la mayoría de las veces sin ser visibilizada, escuchada, sin decidir, sin opinar con autoridad. Sin embargo al pasar el tiempo las mujeres han demostrado tener la capacidad de poder actuar en espacios públicos, de ser tomadoras de decisiones en la vida pública de una sociedad e incluso ser jefas de familia, han llegado a ocupar puestos y han desempañado extraordinariamente cargos que en la antigüedad eran exclusivo para hombres, todo esto derivado de la toma de decisiones de los sectores políticos, de las actividades económicas y del avance de la ciencia y la tecnología. -

Mapa Actualizado Sefisver

Integrantes del Sistema de Evaluación y Fiscalización de Veracruz Sistema de Evaluación y Fiscalización de Veracruz ÓRGANO DE FISCALIZACIÓN SUPERIOR DEL ESTADO DE VERACRUZ Fortalecer: Prevención / Detección / Corrección / Evaluación a los Sistemas de Control Interno / Revisiones Internas ZONA 1 ZONA 2 ZONA 3 ZONA 4 133 01.Cerro Azul 034 01.Cazones de Herrera 033 01.Acajete 001 01.Álamo-Temapache 160 02.Chalma 055 02.Chiconquiaco 057 02.Acatlán 002 02.Benito Juárez 027 152 03.Chiconamel 056 03.Colipa 042 03.Altotonga 010 03.Castillo de Teayo 157 04.Chicontepec 058 04.Gutiérrez Zamora 069 04.Atzalan 023 04.Chumatlán 064 123 05.Chinampa de Gorostiza 060 05.Jalacingo 086 05.Ayahualulco 025 05.Coahuitlán 037 06.Chontla 063 06.Juchique de Ferrer 095 06.Banderilla 026 06.Coatzintla 040 07.Citlaltepetl 035 07.Miahuatlán 106 07.Coacoatzintla 036 07.Coxquihui 050 205 08.El Higo 205 08.Misantla 109 08.Coatepec 038 08.Coyutla 051 09.Ixcatepec 078 09.Nautla 114 09.Jilotepec 093 121 09.Espinal 066 10.Naranjos Amatlán 013 10.San Rafael 211 10.Landero y Coss 096 10.Filomeno Mata 067 11.Ozuluama 121 11.Tecolutla 158 11.Las Minas 107 11.Huayacocotla 072 12.Platón Sánchez 129 12.Tenochtitlán 163 12.Las Vigas de Ramírez 132 161 12.Ilamatlán 076 13.Pueblo Viejo 133 13.Tlapacoyan 183 13.Naolinco 112 150 13.Ixhuatlán de Madero 083 035 14.Tamalín 150 14.Tonayán 187 14.Perote 128 14.Mecatlán 103 15.Tamiahua 151 15.Vega de Alatorre 192 15.Rafael Lucio 136 154 15.Texcatepec 170 16.Tampico Alto 152 16.Yecuatla 197 16.Tatatila 156 129 155 16.Tihuatlán 175 060 17.Tancoco -

New Distributional Records of Freshwater Turtles

HTTPS://JOURNALS.KU.EDU/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSREPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 28(1):146–151189 • APR 2021 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS NewFEATURE Distributional ARTICLES Records of Freshwater . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: TurtlesOn the Roadfrom to Understanding West-central the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s GiantVeracruz, Serpent ...................... Joshua M. KapferMexico 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 Víctor Vásquez-Cruz1, Erasmo Cazares-Hernández2, Arleth Reynoso-Martínez1, Alfonso Kelly-Hernández1, RESEARCH ARTICLESAxel Fuentes-Moreno3, and Felipe A. Lara-Hernández1 . 1PIMVS HerpetarioThe Texas Palancoatl,Horned Lizard Avenida in Central 19 andnúmero Western 5525, Texas Colonia ....................... Nueva Emily Esperanza, Henry, JasonCórdoba, Brewer, Veracruz, Krista Mougey, Mexico and ([email protected] Perry 204 ) 2Instituto Tecnológico. The KnightSuperior Anole de Zongolica.(Anolis equestris Colección) in Florida Científica ITSZ. Km 4, Carretera a la Compañía S/N, Tepetitlanapa, Zongolica, Veracruz. México 3Colegio de Postgraduados, ............................................. Campus Montecillo.Brian J. Carretera Camposano, México-Texcoco Kenneth -

Listado De Zonas De Supervisión

Listado de zonas de supervisión 2019 CLAVE NOMBRE N/P NOMBRE DEL CENTRO DEL 30ETH MUNICIPIO Acayucan "A" clave 30FTH0001U 1 Mecayapan 125D Mecayapan 2 Soconusco 204Q Soconusco 3 Lomas de Tacamichapan 207N Jáltipan 4 Corral Nuevo 210A Acayucan 5 Coacotla 224D Cosoleacaque 6 Oteapan 225C Oteapan 7 Dehesa 308L Acayucan 8 Hueyapan de Ocampo 382T Hueyapan de Ocampo 9 Santa Rosa Loma Larga 446N Hueyapan de Ocampo 10 Outa 461F Oluta 11 Colonia Lealtad 483R Soconusco 12 Hidalgo 521D Acayucan 13 Chogota 547L Soconusco 14 Piedra Labrada 556T Tatahuicapan de Juárez 15 Hidalgo 591Z Acayucan 16 Esperanza Malota 592Y Acayucan 17 Comejen 615S Acayucan 18 Minzapan 672J Pajapan 19 Agua Pinole 697S Acayucan 20 Chacalapa 718O Chinameca 21 Pitalillo 766Y Acayucan 22 Ranchoapan 780R Jáltipan 23 Ixhuapan 785M Mecayapan 24 Ejido la Virgen 791X Soconusco 25 Pilapillo 845K Tatahuicapan de Juárez 26 El Aguacate 878B Hueyapan de Ocampo 27 Ahuatepec 882O Jáltipan 28 El Hato 964Y Acayucan Acayucan "B" clave 30FTH0038H 1 Achotal 0116W San Juan Evangelista 2 San Juan Evangelista 0117V San Juan Evangelista 3 Cuatotolapan 122G Hueyapan de Ocampo 4 Villa Alta 0143T Texistepec 5 Soteapan 189O Soteapan 6 Tenochtitlan 0232M Texistepec 7 Villa Juanita 0253Z San Juan Evangelista 8 Zapoapan 447M Hueyapan de Ocampo 9 Campo Nuevo 0477G San Juan Evangelista 10 Col. José Ma. Morelos y Pavón 484Q Soteapan 11 Tierra y Libertad 485P Soteapan 12 Cerquilla 0546M San Juan Evangelista 13 El Tulín 550Z Soteapan 14 Lomas de Sogotegoyo 658Q Hueyapan de Ocampo 15 Buena Vista 683P Soteapan 16 Mirador Saltillo 748I Soteapan 17 Ocozotepec 749H Soteapan 18 Chacalapa 812T Hueyapan de Ocampo 19 Nacaxtle 813S Hueyapan de Ocampo 20 Gral. -

Coe-173/2021

PROCESO ELECTORAL INTERNO 2020 - 2021 CÉDULA DE PUBLICACIÓN Siendo las 17:00 horas del 01 de marzo de 2021, se procede a publicar en los estrados físicos y electrónicos de la Comisión Organizadora Electoral, ACUERDO COE-173/2021, RELATIVO A LA DECLARATORIA DE VALIDEZ DE LA ELECCIÓN INTERNA MEDIANTE VOTACIÓN POR MILITANTES, CELEBRADA EL 14 DE FEBRERO DE 2021, DE SELECCIÓN DE LAS CANDIDATURAS PARA CONFORMAR LAS PLANILLAS DE LAS Y LOS INTEGRANTES DE LOS AYUNTAMIENTOS DE EMILIANO ZAPATA, PASO DE OVEJAS, PUENTE NACIONAL, ALVARADO, ÚRSULO GALVÁN, TLALTETELA, BOCA DEL RIO, TLALIXCOYAN, MEDELLIN DE BRAVO, COTAXTLA, ATOYAC, CARRILLO PUERTO, PASO DEL MACHO, CUITLAHUAC, SOLEDAD DE DOBLADO, TOMATLÁN, TOTUTLA, COMAPA, HUATUSCO, ALPATLAHUAC, COSCOMATEPEC TEPLATAXCO, SOCHIAPA, TLACOTEPEC DE MEJIA, ZENTLA, AMATLÁN DE LOS REYES, POLPANTLA, FILOMENO MATA, MARTINEZ DE LA TORRES, LANDEROS Y COSS, JILOTEPEC, ALTO LUCERO, MISANTLA, ATZALÁN, NAOLINCO, ALTOTONGA, PEROTE, XALAPA, ACAJETE, BANDERILLA, COATEPEC, IXHUACAN DE LOS REYES, RAFAEL LUCIO, TIHUATLAN, TAMIAHUA, CAZONES DE HERRERA, TIHUATLAN, TUXPÁNX ÁLAMO, BENITO JUÁREZ, CERRO AZUL, CASTILLO DE TEAYO, TANTOYUCA, COXQUIHUI, POZA RICA, TLACHICHILCO, PANUCO, OZULUAMA, TAMALÍN, TEMPOAL DE SÁNCHEZ, CHINAMPA DE GAROSTIZA, CHONTLA, CITLALTEPETL, NARANJOS AMATLÁN, PLATÓN SANCHEZ, TEPETZINTLA, YANGA, ATZACAN, FORTÍN, IXTACZOQUITLÁN, ORIZABA, CORDOBA, IXHUATLANCILLO, NOGALES, TEZONAPA, LOS REYES, XOXOCOTLA, TIERRA BLANCA, CUICHAPA, COSAMALOAPAN, SANTIAGO IXMATLAHUACAN, TRES VALLES, ANGEL R. CABADA, COATZACOALCOS, -

Archivos O Medios Relacionados

Catálogo de las emisoras de radio y televisión del estado de Veracruz Emisoras que se ven y escuchan en la entidad Transmite menos de Cuenta con autorización para Población / Localidad / Nombre del concesionario / Frecuencia / Nombre de la Cobertura distrital Cobertura distrital N° Estado / Domiciliada Medio Régimen Siglas Canal virtual Tipo de emisora Cobertura municipal Cobertura en otras entidades y municipios 18 horas transmitir en ingles o en Ubicación permisionario Canal estación federal local (pauta ajustada) alguna lengua Acayucan, Catemaco, Chinameca, Coatzacoalcos, Cosoleacaque, Hidalgotitlán, Hueyapan de Ocampo, Jáltipan, Jesús Carranza, Juan Rodríguez Clara, 1 Veracruz Acayucan Radio Concesión Radio la Veraz, S.A. de C.V. XHEVZ-FM 93.9 Mhz. Radio Veraz FM 11, 14, 19, 20, 21 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Sin cobertura en otras entidades Minatitlán, Oluta, Oteapan, Pajapan, San Juan Evangelista, Sayula de Alemán, Soconusco, Soteapan, Tatahuicapan de Juárez, Texistepec, Zaragoza Alamo Temapache, Castillo de Teayo, Cerro Azul, Chicontepec, Chontla, Lunes a Domingo: 2 Veracruz Álamo Radio Concesión Radio Comunicación de Álamo, S.A. de C.V. XHID-FM 89.7 Mhz. Radio Alamo FM 1, 2, 3, 5 1, 2, 3, 4 Citlaltépetl, Ixcatepec, Ixhuatlán de Madero, Tamiahua, Tancoco, Tantima, Puebla: Francisco Z. Mena 06:00 a 21:59 hrs. Tepetzintla, Tihuatlán, Tuxpan 16 horas Alamo Temapache, Benito Juárez, Castillo de Teayo, Cazones de Herrera, Cerro Azul, Chicontepec, Chinampa de Gorostiza, Chontla, Citlaltépetl, Ixcatepec, Hidalgo: Huautla, Huehuetla, San Bartolo Tutotepec 3 Veracruz Álamo-Temapache Radio Concesión XHCRA-FM, S.A. de C.V. XHCRA-FM 93.1 Mhz. La Poderosa FM 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Ixhuatlán de Madero, Naranjos Amatlán, Ozuluama, Papantla, Poza Rica de Puebla: Francisco Z. -

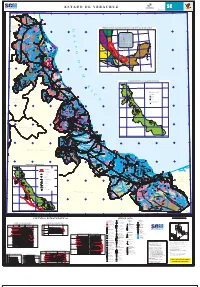

Veracruz.Pdf

94 34’ 22 30’ 94 00’ 30’ 95 00’ 30’ 96 00’ 30’ 97 00’ 30’ 98 00’ 98 42’ 30’ 22 30’ ESTADO DE Qhoal TAMAULIPAS L. LAS PINTAS L. QUINTERO Qhoal L. JOPOY R. Tamesi Qhoal TpaeLu- Ar- Mg . L. LA TORTUGA Qhoal TpaeLu- Ar- Mg L. MAYORAZGO Puente Chairel C. LA TORTUGA A. CORCOVADO - CACALILAO Qhoal TeMg- Lu KcmLu- Mg TomAr- Lu- Lm LAGUNA TpaeLu- Ar- Mg TeMg- Lu EL CHAREL ToAr- Lu- Cgp PLANTA MET` LICA Qholi COMPA ˝A M INERA AUTL` N S.A. DE C.V. UNIDAD TAMOS EL MORALILLO PERSEVERANCIA Qhoal AutlÆn PRIMERO DE MAYO CONGLOMERADO Tamos CHAPOPOTERA ARENISCA Puente Tampico L. CHILA (GRAVA) Qhoal (ARENA, GRAVA) TomAr- Lu- Lm AN` HUAC Qhoal TeMg- Lu TpaeLu- Ar- Mg TomAr- Lu- Lm . CIUDAD CUAHUT MOC Puente PÆnuco TpaeLu- Ar- Mg ARENISCA 87 Qhoal (ARENA, GRAVA) L. TACAT` 90 22 00’ ALUVI N LAGUNA 93 (GRAVA) Qhoeo CONGLOMERADO TomAr- Lu- Lm PUEBLO VIEJO 96 (GRAVA) CONGLOMERADO Mata 99 (GRAVA) de ChÆvez ESTADO DE L. TANCHICU˝N L. LAS OLAS TeMg- Lu CARGADURA DEL GOLFO S.A. DE C.V. TeMg- Lu TAMPICO ALTO G SELECCIONADORA TpaeLu- Ar- Mg CONGLOMERADO DE MATERIAL (GRAVA) CONGLOMERADO (GRAVA) CONGLOMERADO ToAr- Lu- Cgp SAN LUIS Qhoal (GRAVA) TomAr- Lu- Lm 24 R . Qhoeo P P` NUCO Æn uco Qhoal Qhoal a p il To R. R. P TpaeLu- Ar- Mg L E Y E N D A a COA itØ POTOS˝ Qhola L. LAGARTERO Qhoeo 22 00’ TomAr- Lu- Lm Qhoal ` REA MINERALIZADA LLANO DE BUSTOS C. TRES MORILLOS L. -

Procedencia Cuichapa. Salvador Diaz Ortiz 1

PROCESO ELECTORAL INTERNO 2020 -2021 FECHA I DE FEBRERO DE 2021 ACUERDO COEEVER/AYTOS/PRCDNC/046 ACUERDO DE LA COMISION ORGANIZADORA ELECTORAL ESTATAL DE VERACRUZ, MEDIANTE EL CUAL SE DECLARA LA PROCEDENCIA DE REGISTRO DE PRECANDIDATURAS A LAS PLANILLAS ENCABEZADAS POR EL C. SALVADOR D1AZ ORT1Z, PARA EL AYUNTAMIENTO DE CUICHAPA, VERACRUZ, CON MOTIVO DEL PROCESO INTERNO DE SELECCION DE CANDIDATURAS A AYUNTAMIENTOS DEL ESTADO DE VERACRUZ, QUE REGISTRARA EL PARTIDO ACCION NACIONAL, DENTRO DEL PROCESO ELECTORAL LOCAL 2020-2021. EL PLENO DE LA COMISION ELECTORAL ESTATAL DEL PARTIDO ACCION NACIONAL EN VERACRUZ, EN RELACION CON EL PROCESO INTERNO DE SELECCION DE CANDIDATO A LAS ALCALDIAS ACAJETE, ACAYUCAN, ACTOPAN, AGUA DULCE, ALAMO TEMAPACHE, ALPATLAHUA, ALTO LUCERO, ALTOTONGA, ALVARADO, AMATLAN, ANGEL R. CABADA, ANTIGUA LA, ATOYAC, ATZACAN, ATZALAN, BANDERILLA, BENITO JUAREZ, BOCA DEL RIO, CAMERINO Z. MENDOZA, CAMARON DE TEJEDA, CARLOS A. CARRILLO, CARRILLO PUERTO, CASTILLO DE TEAYO, CATEMACO, CAZONES DE HERRERA, CERRO AZUL, CHICONQUIACO, CHINAMPA DE GOROSTIZA, CHOAPAS LAS, CHOCAMAN, CHONTLA, CITLALTEPEC, COATEPEC, COATZACOALCOS, COMAPA, CORDOBA, COSAMALOAPAN, COSCOMATEPEC, COSOLEACAQUE, COTAXTLA, COXQUIHUI, CUICHAPA, CUITLAHUAC, EMILIANO ZAPATA, FILOMENO MATA, FORTIN, HIDALGOTITLAN, HUATUSCO, IXHUACAN DE LOS REYES, IXHUATLANCILLO, IXTACZOQUITLAN, JUAN RODRIGUEZ CLARA, JALTIPAN, JILOTEPEC, JOSE AZUETA, LANDERO Y COSS, LERDO DE TEJADA, MALTRATA, MANLIO FABIO ALTAMIRANO, MARTINEZ DE LA TORRE, MEDELLIN DE BRAVO, MINATITLAN, MISANTLA, NAOLINCO, -

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Veracruz De Ignacio De La Llave Coatzacoalcos COATZACOALCOS 942748 180809 Veracruz De Ignac

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos COATZACOALCOS 942748 180809 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos ALLENDE 942252 180759 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos LAS BARRILLAS 943540 181104 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos EL CEDRO 943126 180805 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos COLORADO 941919 180929 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos LA ESPERANZA 941542 180627 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos FRANCISCO VILLA 941701 180727 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos LA CANGREJERA (GAVILÁN SUR) 942102 180650 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos GAVILÁN SUR BIS 941738 180709 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos GUILLERMO PRIETO (SANTA ROSA) 941636 180939 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos MUNDO NUEVO 942223 180536 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos PAJARITOS 942240 180750 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos LA ESCONDIDA 941519 180907 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos LAS PALMAS 941451 180851 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos SANTA CECILIA 941639 180431 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos EL TIGRILLO 941649 180557 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos LA VERÓNICA (ENTRADA A LA CANGREJERA DOS) 942037 180448 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos PASO A DESNIVEL 943057 180809 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos RINCÓN GRANDE 941949 180701 Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave Coatzacoalcos CINCO DE MAYO 942008 180442 Veracruz -

Dirección General De Gestión De Servicios De Salud Dirección De Gestión De Servicios De Salud

COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE PROTECCIÓN SOCIAL EN SALUD DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECCIÓN DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECTORIO DE GESTORES DEL SEGURO POPULAR VERACRUZ NOMBRE DEL ESTABLECIMIENTO DE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE(S) APELLIDO PATERNO APELLIDO MATERNO SALUD ACAJETE ACAJETE ACAJETE XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS HOSPITAL GENERAL DE OLUTA- ACAYUCAN ACAYUCAN CYNTIA ILEANA CASTILLO LÓPEZ ACAYUCAN HOSPITAL GENERAL DE OLUTA- ACAYUCAN ACAYUCAN SPIRO YELADAQUI CIRIGO ACAYUCAN ACTOPAN ACTOPAN ACTOPAN XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS ACTOPAN CHICUASEN CHICUASEN XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS ACTOPAN PALMAS DE ABAJO PALMAS DE ABAJO XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS TRAPICHE DEL ACTOPAN TRAPICHE DEL ROSARIO XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS ROSARIO ACULA ACULA ACULA BETZABÉ GONZÁLEZ FLORES ACULA POZA HONDA POZA HONDA BETZABÉ GONZÁLEZ FLORES ACULTZINGO PUENTE GUADALUPE PUENTE GUADALUPE RAFAEL POCEROS DOMÍNGUEZ ACULTZINGO ACULTZINGO ACULTZINGO RAFAEL POCEROS DOMÍNGUEZ ÁLAMO TEMAPACHE ÁLAMO HOSPITAL GENERAL ÁLAMO RICARDO DE JESÚS OSORIO ALAMILLA CENTRO DE SALUD CON ALTO LUCERO DE ALTO LUCERO HOSPITALIZACIÓN DE ALTO LUCERO DE MARIELA VIVEROS ARIZMENDI GUTIÉRREZ BARRIOS G.B. COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE PROTECCIÓN SOCIAL EN SALUD DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECCIÓN DE GESTIÓN DE SERVICIOS DE SALUD DIRECTORIO DE GESTORES DEL SEGURO POPULAR VERACRUZ NOMBRE DEL ESTABLECIMIENTO DE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE(S) APELLIDO PATERNO APELLIDO MATERNO SALUD ALTO LUCERO DE PALMA SOLA PALMA SOLA XÓCHITL CORTINA LINAS GUTIÉRREZ BARRIOS HOSPITAL GENERAL ALTOTONGA ALTOTONGA -

Cargo Nombre Juez Lic. Andrés Mora Leo Lic. Nestor

ÚLTIMA ACTUALIZACIÓN: 25 DE MAYO DE 2021 ACAYUCAN JALTIPAN CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ LIC. ANDRÉS MORA LEO SECRETARIO DE ACUERDOS LIC. NESTOR PACHECO FLORES TELÉFONO: 922 2 64 22 62 DOMICILIO: AVENIDA JUÁREZ S/N, COLONIA CENTRO, C. P. 96200 (PALACIO MUNICIPAL) JESÚS CARRANZA CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ LIC. ARTURO ANDRADE LÓPEZ SECRETARIA DE ACUERDOS C. LEONOR SAYALA AYALA TELÉFONO: 924 2 44 02 58 Y 924 2 44 01 81 DOMICILIO: AV. BENITO JUÁREZ S/N, ENTRE INDEPENDENCIA Y 5 DE MAYO, COL. CENTRO, C. P. 96950 (ANTES DE LLEGAR AL PALACIO MUNICIPAL) MECAYAPAN CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ LIC. MARIO REYES GRACIA SECRETARIO DE ACUERDOS VACANTE TELÉFONO: 924 2 19 30 29 Y 924 2 19 30 80 DOMICILIO: CALLE VENUSTIANO CARRANZA S/N, COLONIA CENTRO, C. P. 95930 OLUTA CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ LIC. GENARO GÓMEZ TADEO SECRETARIO DE ACUERDOS C. LUIS EPIGMENIO ALAFITA LEÓN TELÉFONO: 924 2 47 71 51 DOMICILIO: CALLE MANUEL GUTIÉRREZ ZAMORA S/N, ZONA CENTRO O BARRIO PRIMERO, ENTRE HIDALGO Y JUÁREZ, C. P. 96160 SAN JUAN EVANGELISTA CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ LIC. ALFONSO MARQUEZ TORRES SECRETARIA DE ACUERDOS C. HORTENCIA HERNÁNDEZ ROSARIO TELÉFONO: 924 2 41 00 69 DOMICILIO: CALLE FRANCISCO I. MADERO S/N, ENTRE CALLE 16 DE SEPTIEMBRE Y LERDO DE TEJADA, ZONA CENTRO, C. P. 96120 SAYULA DE ALEMÁN CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ LIC. LORENA SÁNCHEZ VARGAS SECRETARIA DE ACUERDOS P.D.D. GRACIELA GRAJALES MARTÍNEZ TELÉFONO DOMICILIO: CALLE LERDO ESQUINA VERACRUZ S/N, ZONA CENTRO, C. P. 96150 SOCONUSCO CARGO NOMBRE JUEZ SECRETARIA DE ACUERDOS LIC. YARA VANNESA GONZÁLEZ GONZÁLEZ TELÉFONO: 924 2 47 23 78; 924 2 45 08 21, 924 2 45 27 98 Y 924 1 06 43 83 (FAX) DOMICILIO: CALLE MIGUEL HIDALGO NO.